Edith Stein, a child of Israel,

a martyr for her people

I. FROM JUDAISM TO CATHOLICISM

BORN FOR GLORY

Edith Stein was born on October 12, 1891 in Breslau, the capital of Silesia, which is today called Wroclaw and located within Poland. She was the eleventh and last child of a Jewish family, four of whom had died in early childhood. She was not even two years old when her father, a wood merchant, died from sunstroke during a business trip. Her mother Augusta, an independent, proud, energetic and capable woman, took control of the business and made it prosper while raising by herself her seven children, in the strict observance of Jewish Law, with its fasting and feasts, and its rabbinical ceremonial, practiced not only at the synagogue, but also at home (…).

At school Edith, who was remarkably talented, soon surpassed her friends, who were all older than she. Since she in no way took pride in this and was always ready to help those less gifted, everybody liked her. “ From my childhood, I have known that goodness is worth more than intelligence, ” she wrote.

At the age of fourteen, she suddenly interrupted her studies, but she took them up again two years later. In the meantime : “ I lost the faith that I had had in my childhood [...] and I consciously and deliberately stopped praying, ” she confessed.

A PHILOSOPHER THIRSTING FOR TRUTH

Once her secondary studies were over, she entered the University of Breslau and soon specialised in philosophy (...).

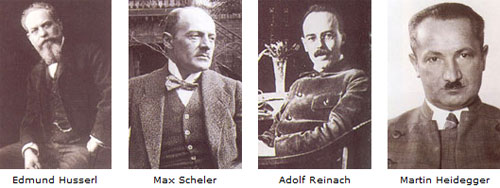

So as not to annoy her mother, she accompanied her to the synagogue, with no conviction. She confessed that she remained an atheist until she discovered the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl, according to which “ to know is once again to receive and to deduce one’s law from objects themselves, and not to determine one’s law and impose it on objects ”. Edith then entered philosophy, as one enters into religious life (…).

“ Phenomenology ” is a scholarly word to express a simple idea. This philosophy was for Edith Stein a deliverance from Kantism that was then in vogue in Germany, as it still is today in French universities (…).

Max Scheler’s classes complemented the phenomenology of Husserl, for whom the questions concerning the individual hardly counted, the study of relations that arise from love, hate, repentance, and that lead to knowledge of other people (…).

A doctor in philosophy since 1916, she was brought by her thirst for knowing the real world to study medieval Christian philosophy and ancient wisdom, that is to say, that of Saint Augustine, Duns Scotus, Saint Thomas, Plato and Aristotle (…).

She immediately understood the interest of the research of Heidegger, the existentialist, as “ a reaction against Husserl’s tendency not to make account for existence and all that is concrete and personal ”. Once again, I can hear my philosophy professor (…).

Her quest for knowledge, however, was not alleviated. Summing up this period of ardent pursuit with a single word, Edith wrote : “ Thirst for truth was my only prayer. ”

This shows that the formalism of her Jewish education had already surrendered whatever priority it had occupied, leaving her soul open to a flood of Christ’s light.

CONVERTED BY THE MYSTERY OF THE CROSS

The conversion of Edith Stein resembles that of Henri Ghéon. The war of 1914 put an end to her studies. Edith spent two years of her life devoting herself to caring for the wounded, in the Mähren hospital in Austria. She received the Red Cross medal (…).

In November 1917, Professor Adolf Reinach was killed on the front, in Flanders. His young widow, Anna, asked Edith to help her classify all of her husband’s philosophical essays, with the intention of a posthumous publication. Without hesitating, she left the University to carry out this duty of friendship. Having witnessed at Gottingen the couple’s intimacy, their happiness, she feared that she would find her friend overwhelmed with sorrow. Anna appeared to her to have been transformed by the trial. Her delicate features were marked by the deep suffering that afflicted her. Christ’s strength, however, dwelled in her soul. The Cross had penetrated to the very innermost part of her being ; it had at the same time wounded and healed her. The sacrifice, borne in love, united this soul to the crucified Saviour. From her entire person emanated a new radiance.

“ It was my first encounter with the Cross, with this divine force that it confers to those who bear it. For the first time, the Church, born of the Passion of Christ and victorious over death, appeared clearly to me. At this very moment, my unbelief gave way, Judaism grew pale to my eyes, while the light of Jesus Christ rose in my heart. The light of Jesus Christ grasped in the mystery of the Cross. This is why, when taking the Habit of the Carmel, I wanted to add to my name that of the Cross ” (…).

Confronted with the attitude of her friend, Edith, who claimed to be atheist, did not show any of the feelings that were troubling her, but the impression that it made on her was indelible (…).

When on vacation in the Palatinate region at the home of the Conrad-Martius family, her Protestant friends, Edith began by going to church with them for Sunday service. She made this observation : “ For Protestants Heaven is closed, but for Catholics, it is open ”. One day in the library, she took a book at random, the Life of Saint Theresa of Avila by Herself.

“ I began reading it ; I was immediately captivated and could not stop before having finished it. When I closed the book, I said to myself : this is the truth. ”

She therefore started studying the catechism, and as soon as she thought that she had sufficient knowledge, she went to the Catholic church to attend Mass :

“ Nothing was foreign to me, she wrote, and I followed the ceremonies to the slightest detail. A venerable priest, Fr. Breitlig, parish priest of Bergzabern, went to the altar and celebrated Mass with a profound recollection. I waited until the end of his thanksgiving in order to meet up with him in the rectory. After a short conversation, I asked to be baptised. He looked at me with great surprise, telling me that a minimum of preparation was required in order to be admitted into the Church :

– ‘ How long have you been instructed in the Catholic faith ’, he asked me, ‘ and by whom ? ’

“ The only reply I managed to stutter out was : ‘ Please, Father, would you question me. ’ ”

A long conversation ensued, during which Edith was examined on the entire Christian doctrine. Full of admiration for the work of grace that God revealed to him in this soul, the priest gave in to her desire. He agreed to baptise her on January 1, 1922. The happy catechumen spent the vigil in prayer, close to the Tabernacle, and was invested with divine grace on the threshold of a new year.

Edith had wanted to add to her own first name that of Theresa in order to express her gratitude towards the saint and that of Hedwig out of affection for her godmother (…).

Immediately after being baptised, Edith made her first Communion, and from then on, the Eucharist became her daily bread (…).

“ MOTHER, I HAVE BECOME CATHOLIC ! ”

born Augusta Courant.

There remained, however, one difficult thing to be accomplished and before which her heart secretly failed her : announce her conversion to her mother (…). She went straight to the point, left for Breslau and went to the family home and there, kneeling down near her mother and looking deep into her mother’s eyes, she murmured with softness and firmness : “ Mother, I have become Catholic. ”

Then, this heroic mother, who for so many years had nobly stood up to trial, overseeing, at the same time, the education of her seven children and the management of the business, this strong woman felt her courage abandoning her, she wept. Edith did not expect this. She had never seen her mother cry ! She had expected reproaches, violence, rupture. Her mother, however, wept. Soon, Edith’s tears mingled with hers (…).

Edith spent six months with her family, surrounding her mother with respect and love. She accompanied her to the synagogue, took part in her fasting and adapted herself to the schedule of her everyday life. Her mother observed her in silence. She confided to a friend : “ I have never seen anyone pray as Edith does. ” She knew that it was useless to try to recover her (…).

Edith Stein met Husserl again : “ […] After each encounter, even as discussion proves to be vain, the urgent necessity of a personal holocaust becomes imperative for me. Whether our present way of life is more or less good, in reality, we cannot say. What we are sure of is that we are here below, presently, in order to work out our salvation as well as that of the souls attached to ours. Of this, there is no doubt. ”

It is the account of this personal “ holocaust ” that we must now relate.

II. THE PREPARATION OF THE VICTIM

A PROFESSOR, A MODEL OF SCIENCE AND CHARITY

From 1923 to 1931, she spent an initial laborious period at Speyer, in the shade of the convent of the teaching Dominicans of St. Magdalena (…). Sharing their poor and secluded lives, she threw herself into Saint Thomas ! She had no intention, however, of becoming a “ Thomist ”. By the forcefulness of her thought, she would be brought to going beyond Saint Thomas, to improve on him, to perfect him with the modern acquisitions of phenomenology and existentialism (…). Edith Stein thus opens a new path : that of a “ Christian philosophy ” a total philosophy that also embraces the truths of the Faith (…).

As a professor of German for the higher classes of the college for young women, Edith prepared her students for State examinations and soon after, young nuns for teaching. “ For us, she was a luminous example, ” wrote the superior (…).

Edith “ had a gift for teaching, wrote her friend, Sister Aldegonde, and she trained us with unlimited patience, with silent and thoughtful kindness […]. ”

“ As for our relations with others, ” she wrote, “ the needs of souls transcend any rule of life. For our personal activities are only ways to strive for an end, while love of neighbour is the very end in itself, since God is Love ” (…).

She gave proficiency lessons to young teachers while speaking to them about current political events and the great social problems of that time, something that was completely new in those days (…).

Fr. Przywara urged her to translate into German the Letters of Newman, then the De Veritate of Saint Thomas Aquinas. She performed both of these tasks perfectly (…).

Fr. Przywara urged her to translate into German the Letters of Newman, then the De Veritate of Saint Thomas Aquinas. She performed both of these tasks perfectly (…).

She then engaged in great activity as a lecturer throughout Germany, with growing success. She expressed herself with tranquil assurance, without a gesture, in a clear and distinct voice (…). She captivated her audience (…).

A PRAYERFUL SOUL COMMUNICATING

IN THE MYSTERY OF THE VIRGIN OF SORROWS

Her days began at 5 o’clock in the morning, and ended at 11 at night. She received Communion every day, recited the Breviary (…).

Sometimes, she remained the entire night close to the Tabernacle and in the morning she went to work without any apparent effort. “ How would such a night have exhausted me ! ” she replied one day, with a smile, evading, in this manner, all explanations (…).

“ Seeing her everyday praying in front of us at Mass, we sensed the mystery, the hidden splendour of a life totally transformed by faith ” (…). From 1928 onward, for Holy Week she would go to the Abbey of Beuron, situated on the banks of the Danube, close to Sigmaringen (…).

Sister Aldegonde recalls : “ How can one forget this expression so grave, unspeakably sorrowful, that she cast on the Crucified One – the King of the Jews – when she read through the unfolding of events the sign of a racial persecution ever more violent. I heard her murmuring one day :

“ ‘ Oh how much my people will have to suffer before they convert ! ’ A thought crossed my mind rapidly, like a bolt of lightening : Edith is offering herself to God for the conversion of Israel ” (…).

On November 22, 1931, she gave a conference before a large Catholic audience at Heidelberg on Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, “ a burning heart, a heart which, through her faithful, tender and delicate love, ravished everyone’s heart. A heart overflowing with love. ” Reread in the light of the events that were to follow, this panegyric appears to be a veritable autobiographical account.

In 1932, she left the Dominicans of Speyer and became a senior lecturer at the Scientific Institute of Pedagogy in Munster. It was not to last. As a “ non-Aryan ” she was soon excluded from teaching by the Nazis. She taught her last class on February 25, 1933.

III. A VICTIM OF EXPIATION FOR THE SALVATION OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

MOUNT CARMEL

On her way to Beuron, where she went for Holy Week, she made a stop at the Carmel of Cologne on the evening of the first Friday of the month of April 1933 : “ I spoke interiorly to the Lord, saying to Him that I knew that it was His Cross that was imposed on our people. Most Jews did not recognise the Saviour, but was it not the responsibility of those who understood, to bear this Cross ? This is what I wanted to do. I only asked Him to show me how. As the ceremony came to an end in the chapel, I received the innermost certainty that I had been answered. I was unaware, however, under what form the Cross would be given to me. ”

We are far from the post-conciliar religion, which no longer speaks of the Cross, nor of the conversion of the Jews, we are rather at the foot of the steep mountain, crowned with a large Cross shown by Our Lady to the three seers of Fatima on July 13, 1917. She understood that her people were going to suffer from the malediction that long ago they called down upon their children (Mt 27 :25). So she offered herself as a victim of expiation to the Mercy of God, in order that the Precious Blood of the Redeemer might effectively sprinkle her people, but in order to draw God’s Mercy on to them, so that God take pity and convert them.

She had long foreseen the scope that the persecution of the Jews would attain. She delivered to Dom Walzer, the prior of Beuron, a message for the Holy Father, warning him that Catholics were just as threatened as were the Jews. Pius XI did not reply to this letter. He was too occupied with his politics : during this year of 1933, a “ Holy Year ”, the jubilee of the Redemption, he signed a concordat with Hitler !

“ Suddenly, it appeared clearly to me that the hand of the Lord struck heavily down on His people, and that the fate of this people became my lot. ” (…)

After a month spent merely observing, her entry was set for October 15, on the feast of Saint Teresa of Avila.

The hardest step of all was to announce the news to her mother (…).

“ My brother-in-law, Biberstein came and found me on the eve of my departure. He was unable to conceal his own point of view : he was unable to understand. It seemed to him that my entry into the convent, at the precise moment when Jews were suffering persecution, caused a break between our people and me. The entirely different point of view that I had adopted escaped him entirely. ”

How would he have been able to understand that Edith was offering herself as a victim like Jesus, for the salvation of her people ? This idea had not dawned on Bergson, for instance, although he was drawn to Catholicism. He refused to convert because he wanted to remain faithful to his people during the persecution. In the end, Bergson did not die a Catholic. Thus, he served no purpose ; he was of no use to anyone. On the other hand, Edith Stein entered straight into the communion of saints :

“ Whoever enters into the Carmel, ” she wrote, “ is not lost to one’s family and friends, quite the opposite, they benefit, for it is our role to stand before God for all ” (…).

THE BRIDE OF JESUS CRUCIFIED

She left a world filled with friends and admirers, in order to enter into the silence of a hidden life. She was received into the community as any other postulant would be, most of the sister were totally unaware of her past and her works. No one thought to admire the newcomer who, nevertheless, won all hearts by her radiant kindness (…).

On Sunday, April 15, 1934, Edith Stein received the Holy Habit and the name of Sister Theresa Benedicta of the Cross. On the day of her temporary profession, on Easter Sunday, April 21, 1935, the radiant peace of Sister Benedicta impressed her entourage. One of her teaching colleagues saw her :

“ Her radiant expression and her appearance of youthfulness remain for me an unforgettable memory. She seemed to have grown twenty years younger and her happiness deeply moved me. However, when I expressed to her my joy at knowing that she was sheltered in the secrecy of Carmel, she replied sharply : ‘ Don’t you believe it ! They will surely come even here to look for me. In any event, I do not expect to be spared. ’ It appeared clear to her that she would have to suffer for her people, in order to fulfil her mission of bringing her family back Home ”(…).

The first shock occurred on the occasion of the plebiscite organised by Hitler on April 20, 1938. The friends of the monastery and the majority of the Carmelites were of the opinion to abstain from voting : a few votes more or less would not change the state of affairs, and they thought it best to go unnoticed, to keep a low profile.

Sister Benedicta, however, usually so mild and submissive, vehemently implored her sisters to vote against Hitler whatever the consequences of such an attitude might be for the community and for each one of them. She pointed out forcefully that Hitler was God’s enemy and he was dragging Germany along with himself into an abyss of evil. She spoke ardently, almost with violence, forgetting all reserve. The community, however, remained hesitant on which course of action to take and discord reigned among the sisters (…).

November 9, 1938. The synagogue of Cologne was burned, the Jews were looted and tracked down ruthlessly throughout the city ! Sister Benedicta seemed dumbfounded with grief : “ It is the shadow of the Cross that casts itself over my people, ” she said. “ Oh ! If only they would give in to reason ! This is the realisation of the malediction that my people called down upon themselves [ “ His Blood be on us, and on our children, ” Mt 27:25 ]. Cain must be punished [Sister Theresa Benedicta compared the Jews killing Jesus to Cain killing Abel], but woe to him who lays a hand on Cain ! [ “ Therefore whosoever slays Cain, vengeance shall be taken on him sevenfold, ” Gn 4:15] Woe to this city, to this country, to these men, on whom divine vengeance will weigh heavy for all the outrages that will be committed against the Jews. ”

But then, it may be asked : Who, therefore, will obtain mercy ? The children of the Church (…).

Given the growing fear of drawing reprisals on her community, Sister Theresa Benedicta obtained the permission from her Mother Prioress to be sent to the Carmel of Echt, in Holland, where she was welcomed with open arms on the evening of December 31, 1938 : “ Her features were marked with gravity and sorrow, ” the sisters said, “ but we were won over from the outset by her delicacy and her big heart. ” Her sister Rose, who had waited for the death of Mrs. Stein before asking to be baptised in turn, came to join her there in the summer of 1940 (…).

PERSECUTION AGAINST CATHOLICS

With the war came persecution against Catholics, as Edith Stein had foreseen from 1933 (…).

With the war came persecution against Catholics, as Edith Stein had foreseen from 1933 (…).

Fully aware of the advice of Our Lord : “ When they persecute you in this city, flee into another ” (Mt 10 :23,) she attempted to flee to the Carmel of Pâquier, in Switzerland, with her sister Rose. The superiors began the well-regulated administrative procedures that attracted the attention of the Gestapo. Summoned to the offices of Maastricht, she replied to the “ Heil Hitler ! ” of the official with a resounding “ Laudetur Jesus Christus ” to the utter amazement of the police officers (…).

The year 1942 was the beginning of the massive deportations to the East. The Catholic bishops and the Protestant ministers wrote a common Pastoral Letter that was read from the pulpit on Sunday, July 26 (…).

The Nazis’ reaction was immediate : they arrested all the priests, religious and nuns of Jewish origin. On August 2, at 17 o’clock, the two Stein sisters were taken away by the Gestapo :

“ Come ! We are going for our people ” murmured Sister Theresa Benedicta to Rose.

Later on, when the religious responsible for the canonical inquiry published the historical account of the facts, he was able to conclude “ After having heard Commissioner Schmidt’s explanations, it can be considered that the religious and nuns apprehended in this manner died as witnesses of the Faith. Their arrest was made out of hatred for the statement of our bishops. It is therefore the bishops and the Church that were designated and struck by the deportation of religious and Catholics of Jewish origin. ”

THE NAZIS’ HATRED FOR CATHOLIC JEWS

The nuns of the small Carmel of Echt were beset with anguish, while awaiting news, when on August 5, two telegraphed messages, identical in their wording, arrived at their convent and at that of the Ursuline’s of Venlo. They were sent from the village of Westerbork, situated in the north of Holland, close to the railroad station of Hooghalen. They were issued by the municipality and requested, in the name of the absent, warm clothes, blankets and medicine (…).

Two young people from Echt agreed to deliver the package as well as mail from the Carmel. They related their visit to the deportees’ camp :

photograph at Echt.

“ […] It was on August 6.

“ The camp, composed of thousands of shacks, was situated about five kilometres from the station. […] At our request, the officers on active duty sent a small Jewish child to the shack where Sister Benedicta and Miss Rose could be found. After a few moments of anxious waiting, we saw the large barbed wire gate open, and in the distance, we caught sight of the brown Habit and the black veil of Sister Benedicta¸ accompanied by Rose. […]

“ The meeting was as poignant as it was joyful. We shook hands and the emotions were so intense that the words stuck in our throats. We handed Sister Benedicta everything that we had been given for her ; she seemed most pleased. She was particularly delighted by the messages from the sisters and the thought that they prayed for her.

“ All of the written texts as well as the Mother Prioress’s letter were handed to her sealed through the Dutch police. Sister Benedicta related that she had found relatives and acquaintances in the camp. She described the trip, which had taken place without incidents as far as Amersfoort. From this station on, however, the prisoners had suffered all sorts of vexations, then they were shoved with blows from the S.S. soldiers’ rifle butts into dormitories and locked in without being given anything to eat. Non-Catholic Jews, however, had received some food. The next morning, the transport set off for Westerbork. This is the place from where the prisoners were able to send telegrams, through the intermediary of the ‘ Jewish councillor ’ responsible for assisting them. This councillor was very kind, especially with the Jewish Catholics. By order of the German authorities, however, Catholic Jews formed a special category, confined in a shack, and on whose behalf the counsellor was strictly forbidden to intervene.

“ Sister Benedict gave this account calmly and with recollection. Her eyes shone with the mysterious brightness of holiness. In a quiet voice, calmly, she related the cruelty suffered by those around her, leaving out all that concerned her personally.

“ She desired above all that the sisters of the Carmel know that she was still wearing her Habit, and that it was her intention and that of the other nuns – there were about ten of them – to keep it to the last.

“ She said that the other prisoners were delighted to have priests and nuns with them. They had become the support and the hope of these poor people, who were expecting the worst. As for her, she said that she was happy to be able to give to others the consolation of a prayer or a word. Her deep faith transformed the atmosphere, around her arose a zone of grace and peace ” (…).

The following passage, from the account of the envoys from Venlo, reveals to us a few additional characteristics :

“ […] When we were taking leave of one another, we were overcome with emotion and we were at a loss for words. The small group went towards the shacks, each prisoner turning back several times to wave farewell. Only, Sister Benedicta went away without turning her head, walking with an even step, most peaceful and collected ” (…).

A VIRGIN OF SORROWS, AN ANGEL OF CONSOLATION

From the mouth of a Jewish shopkeeper from Cologne, responsible for keeping watch on the prisoners of Westerbork, and who with his wife avoided deportation, we have this account :

“ Among the prisoners that arrived on August 5 at the camp – of Westerbork – Sister Benedicta clearly stood out against the group by her peaceful manner and her calm attitude. The cries, the moaning, the state of worried over excitation of the newcomers were indescribable !

“ Sister Benedicta went about among the women like an angel of consolation, calming some, tending to others. Many mothers seemed to have sunk into a kind of shock, akin to madness ; they remained there moaning, as though in stupor, neglecting their children. Sister Benedicta took care of the children, washed them, combed their hair, and obtained food and essential medical care for them. As long as she was in the camp, she dispensed such a charitable assistance around her that it left people deeply moved ” (…).

This stop at Westerbork seems to have lasted from Wednesday morning, August 5, until the night of the 6th to 7th. The camp had one thousand two hundred Jewish Catholics in all, among them there were from ten to fifteen religious. About a thousand of them were deported the same night as Sister Benedicta (…).

On August 6, she wrote a last time to the community of Echt : « Tomorrow the first transport leaves for Silesia or Czechoslovakia […]. I would also like to have the next booklet of our breviary (up to now, I have been able to pray superbly), our proof of identity and our bread ration cards. Many thanks and good-bye to everyone ! »

On August 7, Sister Theresa Benedicta was crammed with a thousand “ Jewish Catholics ” into a train that was bound for the East but whose destination was unknown. In the night, this train made a long stop in her native town of Breslau, where witnesses were able to communicate with her. Then, she was never seen again.

THE TRUE MARTYRDOM OF SISTER THERESA BENEDICTA OF THE CROSS

The death of Sister Theresa Benedicta long remained a mystery. Although it is well-established that she died in a concentration camp on August 9, 1942 (…).

The detained nuns gathered together : a few Trappists, a Dominican, and the Carmelite, forming a small community, the responsibility of which was spontaneously entrusted to Sister Benedicta. She seems to have exerted a real influence over the others by the strength of her deep silence.

A mother, who escaped death, was deeply moved by Sister Benedicta’s attitude.

“ What distinguished her from the other nuns, she wrote, was her silence. I had the impression that she was sorrowful to the depth of her soul, but not anguished. I do not know how to express it, but the burden of her sorrow seemed immense, overwhelming, so much so that when she smiled, this smile came from such a deepness of suffering that it hurt. She hardly spoke, and often looked at her sister, Rose, with an unutterable expression of sadness. She undoubtedly foresaw the fate of both of them. She was the only one of those who had fled Germany who had a premonition of the worst, while the Trappists still harboured illusions, talking among themselves of possibilities of an apostolate.

“ Yes I believe that she was aware, in advance, of the suffering that awaited them, not her own – she was too calm for that, and I would even say : much too calm ! – but the sufferings of the others. Her entire attitude, when I see it again in my mind, as she sat in the shack, brings one thought to mind : that of the Virgin of Sorrows, a Pietà without Christ ”

In fact, like the Blessed Virgin, Edith Stein belongs by flesh and blood to this Jewish people whose rabbinical observances she practiced, still accompanying her mother to the synagogue after her conversion to Catholicism. The flesh, however, has nothing to offer except the victim for the sacrifice, the host for the martyrdom, for which fate Sister Theresa Benedicta offered herself in communion with the Eucharistic Heart of Jesus and Mary, so that her people might understand, open their eyes and convert. Then, the Church coming back herself to the Gospel of Jesus Christ, the Father will be able to forgive everyone, and to cure the rivalries, disputes, civil, racial, ethnic, religious wars that consume the world, and Christendom will come to life again.

Brother Bruno Bonnet-Eymard

Extracts from He is Risen ! n° 8, April 2003, pp. 3-16