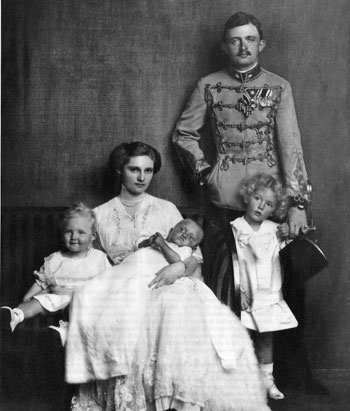

Empress Zita, French princess, Empress and Regent of Austria-Hungary

ONE cannot speak of the Emperor Charles of Austria without mentioning at the same time the figure of his spouse, the Empress Zita. This is because they formed a holy and united couple, both in the days of peace and happiness that did not last and in the tragic years of war and exile.

On the day of their coronation in Budapest, on 30 November 1916, the consecrating bishop had placed the heavy Crown of Saint Stephen on the queen’s shoulder for a moment, saying to her: “Receive the crown of sovereignty, so that you know you are the spouse of the King and that you must always take care of the people of God. The higher you are placed, the more you must be humble and rest in Jesus Christ.”

Following the example of Charles, whose memory she kept alive, she never abdicated her rights, and it was as Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary that she was interred on 1 April 1989, in the crypt of the Capuchins in Vienna. The popular fervour of which she was the object in the course of this ceremony showed an astonished world that, after seventy years of the republic, Zita remained in Austria the Landesmutter, the “mother of the country,” a terrestial image of Her who is venerated at the sanctuary of Mariazell in the heart of the former Empire under the title of “Magna Mater Austriæ, Magna Domina Hungarorum, Mater Gentium Slavorum”.

A RICH AND ‘RELATIONAL’ PAST

She who received at her birth the uncommon name of Zita, the holy patronness of Luca, was born in Tuscany on 9 May 1892, of a Portuguese mother and of a “line of French princes who reigned in Italy,” as her father, Duke Robert of Parma liked to say. With him, we find the legitimist framework that we love, since he was the son of Louise de Bourbon, sister of Henry V. Driven from his States by revolution, he had been raised by his uncle at Frosdorf in Austria. From his two successive marriages he had twenty-four children, of whom six were handicapped. The family was divided between the domain of Pianore in Tuscany, and that of Schwarzau in Austria. Gaiety was in vogue there – they spoke six languages! – and the education given was a mixture of austerity, charity, and profound piety.

Zita had a childhood “particularly joyful and happy.” After four years spent with the Salesian sisters of Zangberg in Bavaria, she lived several months on the Isle of Wight with the Benedictines of Solesmes, who were driven from France by the anticlerical laws. There she found her elder sister who had just taken the veil, as well as their maternal grandmother, Queen Adelaide of Portugal. Braganza, Bourbons of France, of Spain and of the Two Sicilies: Zita belonged to all these royal Catholic houses, now dethroned, which a sort of family pact had connected since the time of Louis XV. “The world was full of cousins,” she later said smilingly.

On her return to Austria in 1909, she was a tall and lovely young girl, of haughty carriage and luminous gaze, pious, lively and gay, who had chosen this as motto: “More for you than for me.” It was then that she met Charles of Habsburg, grandnephew of Emperor Franz-Joseph. On could not find a better representative of traditional Austria: sincerity, charity, tenacity, modesty, Charles had all the qualities that attached upright hearts to him, together with a piety that was surprising to find in a young archduke. “If one does not know how to pray, he can learn from this young gentleman,” said one of his relatives.

On her return to Austria in 1909, she was a tall and lovely young girl, of haughty carriage and luminous gaze, pious, lively and gay, who had chosen this as motto: “More for you than for me.” It was then that she met Charles of Habsburg, grandnephew of Emperor Franz-Joseph. On could not find a better representative of traditional Austria: sincerity, charity, tenacity, modesty, Charles had all the qualities that attached upright hearts to him, together with a piety that was surprising to find in a young archduke. “If one does not know how to pray, he can learn from this young gentleman,” said one of his relatives.

In the enthusiasm of mutual love and with the blessing of Pope Pius X, they were married on 21 October 1911. The following day, they went on pilgrimage to Mariazell to consecrate themselves to “The August Mother of Austria,” as she was called by Ferdinand II when his empire was threatened by the Turks and the Protestants.

Zita had a very thorough sense of tradition; one could even say that her whole personality was “relational.” “All those who preceded me,” she said, “left their mark on my life, and all those who were and are with me, above all the Emperor who gave meaning and fullness to my existence. Without those who have gone before us, we would be nothing. Whatever happened, whatever I have done, I have done it for those who lived before us, those around us, and those who will live after us. Certainly, we have made mistakes, but good will presided over all our enterprises.” (Zita of Habsbourg, Mémoires d’un empire disparu, collected by the historian Erich Feigl, 1991, p. 23)

She added that above all the vicissitudes of history, God alone is sovereign: “A thousand powers, the one Power! All the forces around us that bustle about, pushing or pulling, are nothing beside the only power that rules us. The Emperor Charles was in its service.”

A THREATENED EMPIRE

“The identity of the Danubian region was forged in the struggle against the Turks, and then against Protestantism. In the seventeenth century, Austria was the Catholic rampart of Europe. In the eighteenth century, during the reign of Maria-Teresa [an ancestor of both Charles and Zita,] Austria had incarnated the apotheosis of baroque civilisation [in other words, of the Counter-Reformation.] In 1756, the great Empress concluded a prophetic reversal of alliances with Louis XV: after two centuries of Franco-Austrian wars the new enemy, for Vienna as for Paris, was crouching in Berlin, the capital of Prussia. During the Revolution and the reign of Napoleon, Austria had been the bastion of legitimacy against the new ideas.” (Jean Sévillia, Zita, impératrice courage, Paris, 1997, p. 50)

Situated geographically between the West and the East, the Austria of the Habsburgs had, for the seven centuries of its existence, played a determining federating role for the mosaic of peoples who, although displaying in the heart of Europe an astonishing diversity of statutes, customs, and institutions, were incapable of living and defending themselves alone. Franz-Joseph observed this in 1868: “Within our Empire, the small nations of central Europe find a refuge. Without this common house their fate would be a miserable one. They would become the plaything of every powerful neighbour.” During his reign ( 1848-1916 ) the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary, which Zita would say “incarnated the spirit of European civilisation as did no other state,” was transformed into a modern power with its fifty-one million inhabitants, the forth power in Europe after England, Germany, and France, and experienced a prosperity at the beginning of the twentieth century that aroused much jealousy.

It was, however, above all its overtly political Catholicism that brought down upon the Empire of the Habsburgs the hatred of the enemies of the Church, in particular of Freemasonry. In the year that followed the marriage of Charles and Zita, an international Eucharistic Congress was held in Vienna, at the end of which a friend of the family, Father Andlau, a Jesuit, reported that the Scottish Masonic lodges had sworn the annihilation of Austria-Hungary, obstacle to the creation of a secular and Masonic Europe.

Already the death of Rudolph of Habsburg at Mayerling in 1889 had been, in all likelihood, a Masonic crime. (cf. Michel Dugast Rouillé, L’ombre de Clemenceau à Mayerling, Paris, 1985;) the assassination of Franz-Ferdinand at Sarajevo, on 28 June 1914, was one also. The Archduke, heir to the throne, had divulged to Charles and Zita shortly before:

“I am going to be assassinated.

– But Uncle, that’s not possible! Who would commit such a crime?”

“Uncle Franz-Ferdinand,” Zita commented, “obviously had reasons for believing what he told us. He had had serious threats from nationalist and anarchist groups. Obviously the police had been informed of them and took them very seriously. To tell the truth, the instigators were known to be inaccessible. They mingled and moved in a half-light, and in the political demi-world, between Turin, Paris, and Scotland. They also haunted Belgrade. It was already known at the time that, if an assassination attempt were committed, the authors of it would only be agents manipulated by a ‘big brother.’ ” (Mémoires, p. 123)

THE GUARDIAN ANGEL OF AUSTRIA

Zita, raised by Franz-Joseph to the rank of first lady of the Empire, came to live at Schönbrunn beginning in July 1914. Before leaving for the front at the head of the First Hussars, Charles asked her to have engraved on his sabre the words of their consecration to the Virgin: “ Sub tuum præsidium confugimus, sancta Dei Genitrix. ” On her side, her own brother, Prince Xavier of Bourbon-Parma, who was preparing to join France with Sixtus, wrote in his journal on 20 August 1914:

Zita, raised by Franz-Joseph to the rank of first lady of the Empire, came to live at Schönbrunn beginning in July 1914. Before leaving for the front at the head of the First Hussars, Charles asked her to have engraved on his sabre the words of their consecration to the Virgin: “ Sub tuum præsidium confugimus, sancta Dei Genitrix. ” On her side, her own brother, Prince Xavier of Bourbon-Parma, who was preparing to join France with Sixtus, wrote in his journal on 20 August 1914:

“Today Zita called us to Schönbrunn. She gave us terrible news that, I must say, is in accordance with the moment in which we are living: Pope Pius X is dead. He was the only source of light in this period of darkness. ‘Ignis ardens,’ the ‘burning fire’is no more. I see him again before me; we are all assembled around him, and he is speaking to us as a father to his children. How we were all attentive when he spoke of Zita as of the future Empress of Austria! I see again Mama saying that it was not possible… and here Uncle Franz-Ferdinand is dead. Zita is at Schönbrunn…”

At Court, Zita quickly made an impression by her charisma and her energy. A confidante of the old Emperor, mother of two, then of three lovely children, she gave herself without counting the cost to the most needy, applying the motto of her patroness, St. Zita: “The hands at work, the heart to God.” Watching over the functioning of the hospitals, in the capital and then behind the frontlines, she visited the wounded and organised the relief services. She was, according to the expression of the Cardinal-Archbishop of Vienna, Msgr. Piffl, “the guardian angel of all those who suffer.”

On 21 November 1916, Franz-Joseph drew his last breath after seventy years of reign. He had wanted to punish Serbia, but he had not foreseen that a world war would result, of a new and terrifying type that would be the death-knell of traditional Europe. Why did he enter into war against France and England? Austria had no quarrels with them. This absurd conflict resulted from the distressing German alliance.

SPOUSE AND QUEEN

Jean Sévillia puts it very well: “A monarchy is a family placed at the head of the State.” Charles, who appreciated the political intelligence of his wife, wished her to be directly informed of the great issues of government. With tact and discretion, Zita knew how to assist her husband admirably in his crushing task. General Margutti, received in audience by the young Empress at the end of January 1917, recounts:

Jean Sévillia puts it very well: “A monarchy is a family placed at the head of the State.” Charles, who appreciated the political intelligence of his wife, wished her to be directly informed of the great issues of government. With tact and discretion, Zita knew how to assist her husband admirably in his crushing task. General Margutti, received in audience by the young Empress at the end of January 1917, recounts:

“This time I was again fascinated, not only by the charm that emanated from her august person and by the unrivalled grace of her manners, but more by the turns of her alert and pleasant conversation, sparkling with intelligence and vivacity.” Their exchanges covered the desire of Charles for peace, the implacable determination of the Germans, the risk of the entry of the United States into the war, the danger of events precipitating the fall of Nicholas II and rebounding into that of William II and of the Habsburgs. Zita, however, never encroached on the sphere of the Emperor. Polzer-Hoditz describes the way in which she assisted each evening at the military briefing:

“She was habitually seated a little apart, reading a book or writing letters. Her presence was purely passive. She sometimes asked me for information on such or such an event, but it was never about important affairs. It was rare that she permitted herself to make a remark while the Emperor was discussing political questions with me, but when she did so, the question was always judicious and never beside the point.”

Zita was the soul of the peace negotiations that began to develop beginning in the month of December 1916. It was she who wrote in March 1917 to her brother Sixtus in order to convince him to come to Vienna to learn from Charles himself of his resolution to take Austria out of the war: “Think of all the unfortunates who must live in the hell of the trenches, who are dying by the thousands every day: come!” It was again she who helped her husband to write, in impeccable French, his secret propositions for peace and the reversal of alliances, intended to remove the Monarchy from the German grip and to establish a new Paris-Vienna axis against Berlin. No disloyalty entered into these exchanges. Even with her brothers, she avoided bringing up the internal situation of Austria, though it was becoming more alarming day by day.

PRINCESS OF PEACE

“The Emperor of Austria, secret friend of France? The Germans guessed it. It was difficult for them to attack the Emperor directly. They thus chose another target: Zita. Her French ancestry, in the bellicose speeches of the pan-Germanists, would serve as the pretext for a campaign of disparagement of the Empress. In Germany, she was called “the Frenchwoman,” and in Austria, “the Italian woman.” Within a few months, some would be accusing her of treason.” (Sévillia, p. 96)

Though it was treason for Germany, the project of Charles and Zita was seen in France as the best outcome possible for the war, as shown by a memorandum of the second bureau of army headquarters dated 4 August 1917, of which the author was certainly a disciple of Bainville. This memorandum, supervised by General in Chief Philippe Pétain and transmitted to the Minister of War, Paul Painlevé, stressed the imperative necessity of disassociating the two Empires of Central Europe:

“The only enemy of France, the one danger in Europe is Prussia. The amendments to the constitutions of the other governments are secondary factors as long as Prussia is not entirely and definitely vanquished and reduced to impotence. The Entente must therefore create an irremediably hostile power next to Prussia. It can achieve this through the Habsburgs by forming, with the bond of a personal union, a federation with a majority of Slavic states…”

The same report envisioned that “in case of the break-up of the Danubian monarchy into ethnic and national groups, Germany would find itself faced with small, independent states; Austria itself would opt for anschluss (annexation,) and the Hungarians would seek the support of Germany.”

This prophetic note would have no sequel because Pétain and Painlevé had to cede their positions to the evil duo of Clemenceau-Foch, more avid of power and glory than the true good of France, as the Abbé de Nantes, our Father, has shown. (cf. Les années Pétain : 1918, la gloire éclipsée, CRC n° 303, p. 31).

Charles of Austria had thus failed. “There is something so tragic in the destiny of Emperor and King Charles that one must have lost all sense of spiritual realities not to be moved in seeing the way in which all the aspirations of his soul clashed with the great currents of world politics,” wrote Polzer-Hoditz. The honour of Charles, and that of Zita, “Princess of Peace,” (Antoine Redier, Paris, 1930), consisted in fighting to the end for the peace of Christendom. The judgment of Anatole France is thus applied to both of them, as the homage of vice to virtue: “The Emperor Charles offered peace: he was the only honest man to appear in the course of this war, and he was not listened to… Ribot is an old villain for neglecting such an opportunity. A king of France, yes, a king, would have had pity on our poor exhausted, bleeding, worn-out people!” cité par Michel Dugast Rouillé, le dernier empereur, 1991, p. 89)

FACING THE REVOLUTION

On the domestic front, Charles and Zita found themselves more and more alone as the months passed. He was snubbed by the Viennese aristocracy for his too simple and common manners, heir to a Constitution that imprisoned his reform projects, ill served by ministers who were not equal to the task. When the Emperor, who wanted to keep close contact with his peoples and reinforce their union during the ordeal, decided to convoke the parliament, he soon had reason to regret it: each ‘national’ party rushed to take up pre-war conflicts without regard for the common good. When Charles wanted to repair the denials of justice committed by certain military tribunals with a general amnesty, as a way of pulling the rug out from under his enemies’ feet, he was not understood. This was one of the rare points to which Zita objected, and with reason.

THE THREE HUNDRED FOXES OF SAMSON

One day in January, 1867, Blessed Pius IX asked Don Bosco if he had done well to grant an amnesty to the political prisoners of his States. As the saint hesitated to answer, the Pope insisted :

“Go on, state your idea frankly.

– Your Holiness, by this sovereign stroke of clemency seems to have done what Samson did when he captured three hundred foxes and then let them go. They ran about everywhere, sowing fire and ruin.

– Well, well, you have guessed right. We made a mistake. Wild beasts can be gentled and tamed, but the foxes ‘would lose their coats rather than their vices.’ ”

It was Zita who, in April 1918, was subjected to the affronts of the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Ottokar Czernin, who, in a fit of madness, wanted to use odious blackmail against the imperial family. “The honour of a gentleman,’ Zita calmly retorted, ‘is to protect his sovereign.” The treason of Czernin had disastrous effects, obliging the Emperor to draw closer to Germany and detaching the Slav peoples from the Throne.

A real work of sabotage, orchestrated in London by the Czechs Thomas Masaryk and Edward Benes, and relayed through the Masonic lodges, led about the same time to the insurrectionary creation of “national councils.” More than a million tracts promising independence to the peoples of the Danube were released behind the Austrian lines, while strikes erupted in the industrial centres.

“We must show the people,” said Zita, “that we are there where our duty commands.” It was the maxim of a sovereign. All through the crisis the Empress, who in 1918 became a mother for the fourth time, gave proof of a rare courage. At the end of the summer, she was to be present at a charity gala for the benefit of the war-wounded. Some people warned her against going: she would be booed, the scandal would be tremendous. The Empress decided to face it; she would go. Charles accompanied her. Tense, they appeared at the Konzerthaus in Vienna. In the packed auditorium, there was only profound silence to greet them. Then frenetic applause broke out. After the performance, the sovereigns mingled with the audience. “In all the provinces of the Empire,” Sévillia adds, “in the State, the Church, at all levels of the population, vigorous forces remained faithful to the monarchy. The voice of this silent majority was not heard, however: no effort was made to make it speak.” (p. 124.)

Charles too had shown his character. Probably he committed blunders; probably he had moments of weakness. Nothing, however, had prepared him to succeed Franz-Joseph, and he compels admiration, consideration and compassion when almost always everything turned against him.

“This thirty-year old man,” writes Sévillia, “placed at the head of an old empire, had to face, almost alone, its dissolution. At his side there was no minister of the stamp of Kaunitz or Metternich, no marshal of the character of Eugene of Savoy or Radetzky. Austria had known great men throughout her history; in 1918, she was searching for them.” (p. 147)

THE ASCENT OF CALVARY

The fall of the Empire took place “in the Austrian way,” without bloodshed, the Emperor having refused to defend his throne with arms. When the political circles wanted to push him to abdicate, however, he likewise refused. He did not acknowledge any right for himself to dispose of an authority received from God and blessed by the Church, and Zita still less: “Abdicate? Never!” The imperial family retired to the castle of Echartsau from which, in March 1919, they had to leave the country as outcasts, deprived of their fortune, by the decision of the new “Austro-German Republic,” which was already reaching out to Germany.

From his place of exile in Switzerland, the Emperor continued to fight day after day to prevent this unnatural union, a struggle that would be continued by his family until 1945. His correspondence from that period reveals his broad views of the future and his monarchical convictions, strengthened by the ordeal.

Zita accompanied him in his second attempt at a restoration in Hungary. “In danger,”she said, “the place of the queen is with the king.”It is known how Admiral Horthy, of Calvinist origin but in reality an atheist who detested the Catholic tradition of the Habsburgs, made every effort to cause the attempt to fail. “He came to his own and his own received him not,”would be inscribed by the Hungarian legitimists in the chapel built in the place where the Emperor’s airplane rested on Hungarian soil.

Confined and then exiled to Madera, Charles experienced in the few months he had left to live a spiritual ascension that was the admiration of his spouse. “Even if we have failed in everything,”she said, “we have to thank God, for His ways are not our ways.”Stricken with a double pulmonary congestion, his last days were those of a saint. “I must suffer much so that my peoples can come together again.” In the presence of the Blessed Sacrament, he offered his life in sacrifice and died pronouncing the name of JESUS.

The Empress, who was holding him in her arms, had then an expression of unspeakable dread on her face. Mater dolorosa… Soon, however, her faith got the upper hand and caused her to pronounce the act of heroic abandonment that was to bring her so many graces.

On his side, the Bishop of Funchal testified : “No mission has ever contributed so effectively to revive the Faith in my diocese as the example given by the Emperor in his sickness and his death.” Among the bouquets placed on his tomb in the Nossa Senhora do Monte church, one bore a band on which was written in Portuguese: “to the martyr king.” Five years earlier, in the same language, the Virgin Mary had announced at Fatima: “The good will be martyred.”

THE ORTHODROMY OF THE VIRGIN

It is at Fatima that the divine orthodromy is revealed, the “thread of the Virgin’s thoughts” on the twentieth century. Let us follow its sequence with our Father (cf. CRC 309, janv. 1995.)

Our Lady granted the end of the Great War, announcing on 13 July 1917: “The war is going to end,” as a truce. After the vision of Hell, which should have sufficed to terrorise the good and result in a Crusade of prayer, bringing the reigns of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary over the world… Alas! She announced the possibility, that She knew must be the sad reality of the near future: no attention would be paid to Her appeals, and thus the chastisements would return:

“But if they do not cease to offend God, another, worse one will begin in the reign of Pius XI.”

Jacques Bainville, analysing the treaty signed at Versailles on 28 June 1919, saw it already pregnant with a new war on the part of the same enemy, who would win it! “The damned were not helped to convert,” wrote our Father, “they were kept as heads of nations. They spread everywhere hatred, vices, impiety.” In Central Europe, one of them was distinguished by his anti-Habsburg hatred. It was the Freemason Benes, who was to roar, fifteen years later: “Better Hitler than the Habsburg!” Our Clemenceau, who glorified himself in his memoirs, was no better: “In all of Europe, at last, the words right, liberty, justice, have a meaning… This, we had promised. This, we have done.” The madman!

The Virgin Mary continued : “When you see a night illuminated with an unknown light, know that it is the great sign that God is going to punish the world for its crimes by means of war, famine, and persecutions against the Church and the Holy Father.”

This “unknown light”shone in the night of 25 January 1938. Less than seven weeks later, the Anschluss of Austria by the German army marked the true beginning of the Second World War, with Pius XI still reigning. From Russia, however, was to come an evil more terrible than all the others: “If My requests are heard, Russia will be converted and there will be peace. If not, she will spread her errors throughout the world, provoking wars and persecutions against the Church…” The peoples of the ancient Austria-Hungary were going to suffer in their bodies and their souls.

ADMIRABLE MOTHER

Alone and destitute, with eight children, of whom the last was still to be born, Zita felt “supernaturally united to her husband. Every day she invoked him in her prayers, and more so when difficulties arose.” (Sévillia, p. 207) To the faithful Werkman, who had served as secretary to the Emperor, she confided: “I have one great political duty, and perhaps only that one. I must raise my children according to the mind of the Emperor, to make of them good men who fear God, and above all to prepare Otto for his future. None of us knows what that is.”

Welcomed by the Spain of Alphonso XIII, the family settled in the very Catholic little village of Lekeitio, on the Basque coast, until 1930, before going to Belgium at the invitation of Albert I and Queen Elizabeth. Three sentences would be sufficient to sum up the instruction that this admirable mother, a worthy imitator of Blanche of Castille, was giving her children.

Finding one of her ladies-in-waiting in tears one day, she learned that there was not enough money left to buy provisions for the week. She was then heard to murmur, “All the same, it is a great thing to be at this point in the hands of God!”

Otto had been kept in his room for two days while the shoemaker resoled his one pair of shoes: “Thus,” said the Empress, “he will understand the poor and will really be their king!”

Another day, she called him and spoke seriously to him. The newspapers had just announced that the crown prince of Italy had been the victim of an attack in Brussels that nearly cost him his life: “I want you to learn from me, my child, what has just happened and that it concerns you; for miserable men will perhaps want to kill you too. You must know it, and be ready to fall at any moment of your life, as a Christian and a King.” (Marie-Madeleine Martin, Othon de Habsbourg, prince d’Occident, Paris, 1959, p. 145)

It was, however, towards Austria, the mother country, that their hearts ceaselessly turned.

STRUGGLE FOR AUSTRIA

The treaty of 1919 had created an unliveable Austria, which had to reconvert its activities completely in order to acquire a satisfactory economic equilibrium. Placed at the head of a state of which the financial situation depended on loans agreed to by the League of Nations, Msgr. Seipel, who had become Chancellor, had to sacrifice to its pacifist internationalism. When the crisis occurred, and with it unemployment and class struggle, a new chancellor, Dollfuss, set up in 1933 a “federal, corporative, and Christian state” in imitation of that of Dr. Salazar in Portugal. On 11 September 1933, he had celebrated the 250th anniversary of the victory over the Turks at the siege of Vienna. “Exalting the Christian vocation of Austria against the barbarians encamped at the gates of the city, he provoked the admiration of the crowd, who understood the symbol.” The modern barbarians were the Nazis.

Hitler understood him too, and wanted to finish off the little man who flouted him. On 25 July 1934, Berlin masterminded a putsch organised by the Austrian Nazis. The putsch miscarried, but a henchman struck down the Chancellor. “The first bloody victim of Nazism, he died for having carried on, alone and intrepid, the combat for the faith and the liberty of his country, in a Europe that was sleeping.” (Sévillia, p. 228)

Let us be finished once and for all with the legend: Austria was not the cradle of National-Socialism! If Hitler was an Austrian, he had denied his country and built his career on negation of the Austrian spirit. Austria benefited then from the support of Mussolinian Italy, but the situation changed in 1937: the war in Ethiopia and the stupid sanctions with which the Allies thought it necessary to strike Italy only brought Rome closer to Berlin. Schuschnigg, who had succeeded Dollfuss, was summoned on 12 February 1938 to Berghof by Hitler. Already the plan for the invasion of Austria by the Wehrmacht was ready, and bore the name of “Otto.”

Reading the thrilling pages of Sévillia on this period, we realise that the legitimist movement had spread to such an extent in Austria that tens of thousands of students, workers, and peasants yearned for the return of the son of the Emperor Charles. The very name of Habsburg incarnated the independence of Austria; the song Edelweiss was on all lips. The announcement of the plebiscite set for 13 March 1938, however, provoked an ultimatum from Berlin. Schuschnigg was forced to resign and soon, at Linz, Hitler decreed the Anschluss, that is to say the union, the forced integration of Austria into the Fourth Reich – amid international indifference.

From Belgium, Zita and Otto had followed the events hour by hour, in anguish. Heart to heart with their faithful people caught up in the turmoil – most of the leaders of legitimist groups would die in concentration camps, and those who escaped the raids fought in the front line for the freedom of Austria – the exiled sovereigns carried on the same combat.

As refugees in the Unites States from 1940, Otto and his brothers, but also Zita, their discreet and attentive counsellor, multiplied approaches to Roosevelt and Churchill so that Austria might be listed among the number of countries occupied by Hitler and that it would thus be spared at its liberation. They were successful, and it was thanks to a speech that the Empress gave in 1948 to the wives of members of Congress that Austria was accepted as a beneficiary of the Marshall Plan for the reconstruction of Europe. This was “the last political act of Zita.” It can be said that, at a distance, she was during these years of suffering and anguish, the lightning rod of Austria.

It was still necessary for her people to join with her.

THROUGH PRAYER AND PENANCE

Liberated Austria was divided in May 1945 into four zones occupied by the victors: Soviet Russia, the United States, England, and France. At Vienna, General Tolbukhin, commanding the Soviet occupation forces, supported the Socialist Karl Renner – who, in 1938, had applauded the Anschluss! – to form a provisional government. As the years passed, however, the USSR showed no desire to leave, for Austria represented too precious a base of operations in the heart of Europe: “What we occupy, we never give up,” declared one of its directors. In 1955, nevertheless, Moscow accepted, in an unhoped-for fashion, the complete withdrawal of its occupation forces. What had happened?

At the origin of this “miracle” we find a Franciscan of the name of Petrus Pavlicek. On 2 February 1946, this valiant popular missionary went to the sanctuary of Mariazell to ask “the august Mother of Austria” what he should do. During his prayer he heard a voice saying to him:

“Do what I tell you and you will have peace.”

Remembering Fatima, he obtained from his superiors permission to launch a crusade of prayer by means of the rosary and of penance, in a spirit of reparation and expiation. Missions were organised throughout the country, so well that in 1954 the Crusade counted more than a million members – a tenth of the population – with at their head the Chancelor Figl, who engaged himself to recite the rosary daily. Each year, for the feast of the Holy Name of Mary, a great procession went through the capital. Between 10 and 15 May 1955, international agreements gave back to Austria its full independence.

On the other side of the eastern frontier, events had taken a far more dramatic turn. Hungary, with its seven million Catholics out of ten million inhabitants, had been delivered over to Bolshevism by the Yalta accords. Named Archbishop of Esztergom and Primate of Hungary on 7 October 1945, Cardinal Mindszenty wanted to be “the good shepherd who, if necessary, gives his life for his sheep, his Church, his homeland.” Foreseeing that terrible persecutions were going to descend upon the Regnum Mariae, he declared a Marian year devoted to Fatima on 15 August 1947, to the great fury of the Communist government: “These days of Mary must reinforce the Catholic conscience; remain Catholic and Hungarian! Keep away from false prophets. They sow hatred and gather the fruits of their own interests. May the Hungarians be the people of Saint Stephen and of the Mother of God!”

The Marian year was scarcely ended when the Prince-Primate was arrested. Imprisoned, dreadfully tortured, he was condemned to perpetual forced labour at the end of a mock trial that accused him of counter-revolutionary intrigues in league with Otto von Habsburg, on the pretext that he had met Otto at the Marian Congress in Ottawa in 1947!

He was liberated during the uprising of 1956, then constrained to take refuge in the American Embassy in Budapest, which he left in September 1971. Removed from office by Pope Paul VI as an embarrassing obstacle to the Vatican’s Ostpolitik, he went in May 1972 to Zizers in Switzerland to meet… the Empress Zita, the last crowned Queen of Hungary, and to celebrate the Mass for her eightieth birthday. The following 13 October he preached prayer and penance at Fatima in order to try to awaken our old Catholic nations!

THE OTHER EUROPE THAT IS ROMAN

In 1982, Zita could once again at last set foot on Austrian soil. In contrast to her son Otto – who had renounced his rights at the end of the nineteen-fifties in order to return to the country, assuage his democratic passion and be elected to the European Parliament! – she had never given in. “Not through pride,” Sévillia stresses, “but out of fidelity to the memory of Charles.” After a pilgrimage of thanksgiving to Mariazell, she was greeted by an enthusiastic crowd in Vienna on 13 November 1982, before going to the Tyrol, a bastion of legitimist fidelity.

In 1982, Zita could once again at last set foot on Austrian soil. In contrast to her son Otto – who had renounced his rights at the end of the nineteen-fifties in order to return to the country, assuage his democratic passion and be elected to the European Parliament! – she had never given in. “Not through pride,” Sévillia stresses, “but out of fidelity to the memory of Charles.” After a pilgrimage of thanksgiving to Mariazell, she was greeted by an enthusiastic crowd in Vienna on 13 November 1982, before going to the Tyrol, a bastion of legitimist fidelity.

In the beginning of 1989, she knew one final joy in learning that her son Otto had also been received triumphantly in Budapest, and that the Iron Curtain was cracking: “The Habsburg in Hungary, liberty for the Danubian peoples? God is great! I must join Him – the mission is finished,” the ninety-seven year old Empress said, smiling, before dying on 14 March 1989.

Well, no! Her mission is not finished, nor is that of Charles, whom Maurras honoured with the title of “True European gentleman,” if it is true that in Heaven one can still work for the Kingdom of God on earth. That Kingdom is far from being established in Central Europe! After having endured passion and death under the yoke of the Nazis, then under that of the Soviets, these peoples have fallen back into the disorder created by the Allies in 1919-1920. Still worse, since 1993 a split has occurred between the Czech Republic and Slovakia, while the countries of the ex-Yugoslavia gave themselves over to war to the death.

Then, “Austria-Hungary, an idea of the future,”as Professor Pierre Béhar claims? Yes, but on the condition that these fraternal peoples be liberated from the democratic virus and returned to their legitimate sovereigns, under the aegis of Roman authority. Our Father developed on this subject exciting ideas, to which we will perhaps have the occasion to return.

frère Thomas de Notre-Dame du perpétuel secours.