Qurʾān - Glossary

Many people may be surprised by some of the affirmations made in this glossary. It must be kept in mind, however, that they are either conclusions drawn after in-depth studies or scientific insights sometimes established long ago that have never been refuted, although often they have been suppressed. After thoroughly studying Brother Bruno’s translation and commentary, readers will come to understand that these affirmations are neither exaggerated nor outrageous, but fully justified.

“The truth shall make you free.” (Jn 8:32)

- A

Aelius Gallus (Gaius) ◊ Second prefect of the Roman province of Egypt Roman prefect of Egypt from 26 to 24 b.c. in the reign of Augustus. Aelius Gallus is primarily known for a disastrous expedition he undertook to Arabia Felix (modern day Yemen) by the command of the emperor.

Aelius Gallus (Gaius) ◊ Second prefect of the Roman province of Egypt Roman prefect of Egypt from 26 to 24 b.c. in the reign of Augustus. Aelius Gallus is primarily known for a disastrous expedition he undertook to Arabia Felix (modern day Yemen) by the command of the emperor.

An account of the expedition to Arabia Felix, which turned out to be a complete failure, is given by the Greek geographer Strabo, as well as by Cassius Dio and Pliny the Elder. Aelius Gallus undertook the expedition from Egypt, with a view to explore the country and its inhabitants, and to conclude treaties of friendship with the people, or to subdue them if they should oppose the Romans.

When Aelius Gallus set out with his army, he trusted to the guidance of a Nabataean called Syllaeus, who deceived and misled him. Strabo, who derived most of his information about Arabia from his friend Aelius Gallus, wrote a long account of this expedition through the desert. The scorching heat of the sun, bad water, and disease destroyed the greater part of the army; so that the Romans, unable to subdue the Arabs, were forced to retreat. Aelius Gallus returned to Alexandria and was eventually recalled by Augustus for failure to pacify the Kushites.Aggadah (pl. aggadot), halakhah (pl. halakoth), and midrash (pl. midrashim) ◊ are rabbinic narrative and interpretive literary technics. Aggadah refers primarily to legends, most of which have their origin in rabbinic commentaries on the biblical text, or in the lives of the sages and heroes of Jewish history. They are exegetical or homiletical in nature. Halakhah, on the other hand, refers to the branch of rabbinic literature that deals with interpreting the religious obligations of Jews to God and neighbour.

Often these two literary technics are used together, successively. A halakhah is, in fact, the practical, moral, ritual or legal application of the preceding aggadah. Such is the case in the Qurʾān. Each of the sūrahs that Brother Bruno has studied, begins with an aggadic narrative in which the author proposes episodes from sacred history as figures of events that he himself is accomplishing or that he foresees. To do this, he reshapes the biblical text to reflect contemporary events in a suggestive way. The second part of these sūrahs is a halakhic legal interpretation of this aggadah. In constructing his sūrahs in this way, the author of the Qurʾān is perhaps deliberately imitating the epistles of Saint Paul in which a paraenesis follows a dogmatic exposition in a well-balanced construction of two parts of strictly equal importance.

Midrash refers to ancient rabbinic interpretation of scripture. They are termed midrash aggadah if they provide moral instruction by using various literary genres: stories, parables and legends; or midrash halakhah if their purpose is to explain various legal points.Aigrain (Chanoine René) ◊ Professor and author (1886-1957). He entered the Major Seminary of Poitiers in 1904 and was ordained priest in 1909. He became professor of the History of the Middle Ages at Université catholique d’Angers in 1923, where he taught until 1951. He was appointed Honorary Canon of Poitiers in 1934. From 1922 to 1924, he contributed the article Arabia to the Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques. It is a complete encyclopaedia on the question of Christian origins in Arabia, supported by a rigorous critical analysis of the positive data known at the time. In it, he rightly concluded that “we can no longer deal with the history of Muḥammad by using, as several of his biographers do, the Sīrah as a basis.” Unfortunately, when it came Islam, he abandoned this fruitful point of view, simply reverting to the use of what is considered to be traditional data, immediately adding to the above remark: “This does not mean that we must retain nothing from it [the Sīrah], which would make it absolutely impossible for us to know the life of the Prophet.” This means that even outside the Sīrah there is not one single positive fact that attests to Muḥammad’s historical existence.

Al-Nuwayrī ◊ Arab historian and jurisconsult in the service of the Mameluke Sultans of Egypt. (1279-1333). Born in An Nuwayrah, Egypt, he left an encyclopaedia entitled Nihayat al-arab fi funûn al-adab (All You Wish to Know about Belles-Lettres), in 30 volumes, covering all aspects of human history, as well as fauna, flora, laws, geography, the art of governing, poetry, recipes of all kinds, humorous stories and the revelation of Islam. He was also the author of Chronicle of Syria and History of the Almohads of Spain and Africa.

Alids ◊ Those who claim descent from the caliph Ali and Fatima, respectively the purported son-in-law and daughter of the hypothetical Muḥammad.

Amram Gaon ◊ Head of the Talmud Academy († 875). He was a famous Gaon or head of the Jewish Talmud Academy of Sura during the 9th century. His chief work was liturgical. He was the first to arrange a complete liturgy for use in the synagogue. His Prayer Book, Siddur Rab Amram, has exerted great influence upon Jewish religious practise and ceremonial for more than a thousand years, an influence which to some extent is still felt at the present day.

Aramaic ◊ A Semitic language known since the 9th century b.c. as the speech of the Aramaeans and later used extensively in southwest Asia as a commercial and governmental language and adopted as their customary speech by various non-Aramaean peoples including the Jews after the Babylonian exile.

Arnaldez (Roger) ◊ Professor of Philosophy, author and orientalist (1911-2006). He authored some thirty works on Islam, medieval philosophy and the thought of Averroes. He began Islamic studies after earning his university degrees as professor of Philosophy. Although profoundly Christian, Arnaldez was a man of dialogue. All his life, he worked in the service of what he called “the spiritual values of a religious humanism.” He was partisan since the 1930s of an ecumenical approach and openness to other religions. He served as consultant to the section for Islam of the Vatican Secretariat for Non-Christians. He was also an active member of the Jewish-Christian Friendship Association of France. Professor at the University of Lyon from 1956 to 1968, then at the University of Paris-Sorbonne until 1978, he was elected in 1986 to the French Academy of Moral and Political Sciences. His international reputation earned him an associate membership in the Royal Academy of Belgium, and a corresponding membership in the Academy of Arabic Language in Cairo. In 1980, Roger Arnaldez, publishing a book under the somewhat enigmatic title of Jesus, Son of Mary, Prophet of Islam, opened a new avenue of research. It was not the hackneyed comparison of the Qurʾānic Jesus with New Testament sources, but the meticulous exploration of the commentaries of the Qurʾān in order to bring out the completely Muslim figure of Christ that they reveal.

Arnaldez (Roger) ◊ Professor of Philosophy, author and orientalist (1911-2006). He authored some thirty works on Islam, medieval philosophy and the thought of Averroes. He began Islamic studies after earning his university degrees as professor of Philosophy. Although profoundly Christian, Arnaldez was a man of dialogue. All his life, he worked in the service of what he called “the spiritual values of a religious humanism.” He was partisan since the 1930s of an ecumenical approach and openness to other religions. He served as consultant to the section for Islam of the Vatican Secretariat for Non-Christians. He was also an active member of the Jewish-Christian Friendship Association of France. Professor at the University of Lyon from 1956 to 1968, then at the University of Paris-Sorbonne until 1978, he was elected in 1986 to the French Academy of Moral and Political Sciences. His international reputation earned him an associate membership in the Royal Academy of Belgium, and a corresponding membership in the Academy of Arabic Language in Cairo. In 1980, Roger Arnaldez, publishing a book under the somewhat enigmatic title of Jesus, Son of Mary, Prophet of Islam, opened a new avenue of research. It was not the hackneyed comparison of the Qurʾānic Jesus with New Testament sources, but the meticulous exploration of the commentaries of the Qurʾān in order to bring out the completely Muslim figure of Christ that they reveal.Ashkenazi (Shmuel) ◊ Israeli philologist and author (1922-....). Born Samuel Deutsch, this Israeli philologist was an author of collections and dictionaries of proverbs and abbreviations. He was co-author of Ozar rashe tevot, a thesaurus of Hebrew abbreviations.

Axum (Kingdom of) ◊ The Axumite kingdom, centred in Northern Ethiopia, in the Tigray region as well as what is now Eritrea, is first mentioned in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a description of the coasts of the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean written in the latter half of the 1st century a.d. The author describes the port of Adulis and states that “eight day’s journey inland lay the metropolis of the Axumites, whither was carried all the ivory from beyond the Nile and whence it was exported to Adulis and so to the Roman Empire.” The Axumite kingdom existed from approximately 80 b.c. to 825 a.d. A major transformation of the maritime trading system that linked the Roman Empire and India took place around the start of the 1st century. The Axumite kingdom benefitted from it to such a point that it was able to eliminate the rival and much earlier trading network of the Kingdom of Kush that had long supplied Egypt, and through it, the Roman Empire with African goods via the Nile corridor. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea explicitly describes how ivory collected in Kushite territory was being exported through the Axumite port of Adulis instead of being taken to Meroë, the capital of Kush. In order to supply African goods, such as ivory, incense, gold, slaves, and exotic animals, the kings of Axum worked to develop and expand an inland trading network. From the late 3rd century on, Axumite rulers also assured their hegemony over trade by minting their own currency that bore legends in Ge’ez and Greek.

Before their conversion to Christianity, the pagan Axumites practiced a polytheistic religion related to those practiced in southern Arabia. This included the use of the crescent-and-disc symbol. King ʿEzana was converted to Christianity during his regency (325-328) by his tutor, Frumentius (see the articles: ʿEzana and Frumentius in the glossary). This conversion is attested in stone and numismatic inscriptions. Early inscriptions show that King ʿEzana worshiped the gods Mahrem, Beher and Medr. Later inscriptions during his reign are clearly Christian and refer to “the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.” On coins, the pagan crescent-and-disc symbol was replaced with the Cross. Later on, unfortunately, the Church of Axum founded by Frumentius followed the Church of Alexandria into the Orthodox schism by rejecting the Fourth Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon (451). It thus became a Miaphysite church; its scriptures and liturgy conserve the ancient Ge’ez language.

Around 520, King Kaleb sent an expedition to Ḥimyar against the Jewish king Yūsuf Dhū Nuwās who was persecuting the Christian community there. Dhū Nuwās was deposed. For nearly half a century south Arabia would become an Axumite protectorate. Kaleb appointed a Christian Ḥimyarite, Esimiphaios, as his viceroy. This viceroy, however, was deposed around 525 by the Axumite general Abraha with support of Axumites who had settled in Ḥimyar, and withheld tribute to Kaleb. When Kaleb sent an expedition against Abraha, this force defected, killing their commander, and joining Abraha. Another expedition sent against him was defeated, leaving Ḥimyar under Abraha’s rule, although he resumed payment of a tribute, and continued to promote the Christian faith until his death.

After Abraha’s death, his son Masruq Abraha continued the Axumite vice-royalty in Yemen, paying tribute to Axum. However, his half-brother Ma’d-Karib revolted. After being denied by the Byzantine emperor Justinian, Ma’d-Karib sought help from Khosrow I, the Sassanid Persian Emperor, thus triggering the Axumite-Persian wars. Khosrow sent a small fleet and army under commander Vahrez to depose Masruq. The war culminated with the Siege of Sana’a, capital of Axumite Ḥimyar. After its fall in 570, and Masruq’s death, Ma’d-Karib’s son, Saif, was put on the throne. In 575, the war resumed again, after Saif was killed by Axumites. The Persian general Vahrez led another army and brought Axum rule in Ḥimyar to an end, becoming himself the hereditary governor of Ḥimyar. These wars, with an overall weakening of Axumite authority and over-expenditure in money and manpower, made Axum lose its status as great power. After a second golden age in the early 6th century the empire began to decline in the mid-6th century, eventually ceasing its production of coins in the early 7th century. Around this same time, the Axumite population was forced to go farther inland to the highlands for protection, abandoning Axum as the capital.- B

Baron (Salo Wittmayer) ◊ Polish-born American historian (1895- 1989). Baron was born into an educated and affluent aristocratic Jewish family of Galicia (in present-day Poland). His first language was Polish, but he knew twenty languages, including Yiddish, biblical and modern Hebrew, French and German, and was famous for being able to give scholarly lectures without notes in five different languages. Baron received rabbinical ordination at the Jewish Theological Seminary in Vienna in 1920, and earned three doctorates from the University of Vienna, in philosophy (1917), in political science (1922) and in law (1923). He began his teaching career at the Jewish Teachers College in Vienna in 1926, but was persuaded to move to New York to teach at the Jewish Institute of Religion.

Baron (Salo Wittmayer) ◊ Polish-born American historian (1895- 1989). Baron was born into an educated and affluent aristocratic Jewish family of Galicia (in present-day Poland). His first language was Polish, but he knew twenty languages, including Yiddish, biblical and modern Hebrew, French and German, and was famous for being able to give scholarly lectures without notes in five different languages. Baron received rabbinical ordination at the Jewish Theological Seminary in Vienna in 1920, and earned three doctorates from the University of Vienna, in philosophy (1917), in political science (1922) and in law (1923). He began his teaching career at the Jewish Teachers College in Vienna in 1926, but was persuaded to move to New York to teach at the Jewish Institute of Religion.

Baron’s appointment as the Nathan L. Miller Professor of Jewish History, Literature and Institutions at Columbia University (1930-1963) marked the beginning of the scholarly study of Jewish History in American universities. Baron is considered the greatest Jewish historian of the 20th century. He was opposed to the “lachrymose conception of Jewish history,” of the 19th century, although he recognised that “suffering is part of the destiny of the Jews.” His most important work was originally a three-volume overview of Jewish history published in 1937, entitled A Social and Religious History of the Jews. He kept working on it over his lifetime and it eventually grew to 18 volumes Professor Baron strove to integrate the religious dimension of Jewish history into a full picture of Jewish life and to integrate the history of Jews into the wider history of the eras and societies in which they lived.

After World War II, Baron ran the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Inc., an organisation established in 1947 to collect and distribute heirless Jewish property in the American occupied zones of Europe. Hundreds of thousands of books, archives, and ceremonial objects were distributed to libraries and museums, primarily in Israel and the United States. From 1950 to 1968, he directed the Centre of Israel and Jewish Studies at Columbia University. Becker (Carl Heinrich) ◊ German orientalist and politician (1876-1933). Becker was one of the Wilhelmine period’s most eminent orientalists and is considered a co-founder of modern and contemporary Oriental studies in Germany. He was at the same time an important reformer of academics in the Weimar Republic. In 1921 and from 1925 to 1930, he was Prussian Minister of Education.

Becker (Carl Heinrich) ◊ German orientalist and politician (1876-1933). Becker was one of the Wilhelmine period’s most eminent orientalists and is considered a co-founder of modern and contemporary Oriental studies in Germany. He was at the same time an important reformer of academics in the Weimar Republic. In 1921 and from 1925 to 1930, he was Prussian Minister of Education.

His comparative analysis of Christianity and Islam, entitled Christentum und Islam (1907), represents the first major work of modern oriental studies. For Becker, Christianity and Islam present a complex parallel historical development, being religious systems that are fundamentally similar, which only diverge at the point of the Renaissance. Becker was introduced to oriental studies through Old Testament criticism, the field’s traditional point of entry. He quickly adopted the modern Orient as his object of study. In 1908, Becker accepted an appointment at the Kolonialinstitut in Hamburg, an important training ground for Germany’s colonial and overseas administrators. While in Hamburg, Becker aggressively advocated the implementation of Islamwissenschaft (the scientific study of Islam) on behalf of Germany’s colonial project. Becker’s first publication at Hamburg, Islam and the Colonisation of Africa (1910), a none- too-subtle treatise on racial and religious hierarchies in Africa, exemplified his deep commitment to Islamwissenschaft. Becker had a tendency to adapt his writings for use by the colonial establishment that he served. The publication of Christianity and Islam represents a liminal moment in Becker’s academic career when was no longer a traditional orientalist but not yet a crude mouthpiece for German colonial ambitions Ben Abd-el-Jalil (Jean Mohammed) ◊ Moroccan Catholic priest (1904-1979). Ben Abd-el-Jalil was born into a family of Muslim notables from Fez on April 17, 1904, Mohammed Ben Abd-el-Jalil received a bilingual and Muslim education. He began by learning the Qurʾān at the University of Al Quaraouiyine in Fez, and then accompanied his father on a pilgrimage to Mecca at the age of 9. Between 1922 and 1925, he attended the Gouraud High School while boarding at the Foucault School, run by Franciscan Fathers in Rabat, the capital of the French Protectorate in Morocco. It was at this time that Mohammed developed an interest in the Catholic religion. He obtained his baccalaureate in 1925.

Ben Abd-el-Jalil (Jean Mohammed) ◊ Moroccan Catholic priest (1904-1979). Ben Abd-el-Jalil was born into a family of Muslim notables from Fez on April 17, 1904, Mohammed Ben Abd-el-Jalil received a bilingual and Muslim education. He began by learning the Qurʾān at the University of Al Quaraouiyine in Fez, and then accompanied his father on a pilgrimage to Mecca at the age of 9. Between 1922 and 1925, he attended the Gouraud High School while boarding at the Foucault School, run by Franciscan Fathers in Rabat, the capital of the French Protectorate in Morocco. It was at this time that Mohammed developed an interest in the Catholic religion. He obtained his baccalaureate in 1925.

That same year, he went to Paris for higher studies to obtain a degree in Arabic language and literature. He was also interested in philosophy and theology, frequenting Jacques Maritain, Maurice Blondel, and especially Louis Massignon, who maintained a long friendship and correspondence with him. The celebration of Christmas 1927 was an important step in his conversion, and he asked to be baptised. He was baptised the following year on April 7, in the chapel of the Franciscan College in Fontenay-sous-bois, with the Orientalist Louis Massignon as his godfather. He chose Jean as his Christian name. In 1929, he entered the Franciscan Order, and was ordained a priest in 1935.

In the 1930s, he published anonymously in the magazine En terre d'Islam, an appeal “proposing to the faithful to devote Fridays to pray for our distant brothers." He also founded a “Friday Prayer League for the conversion of Muslims.”

In 1936, he was called as a professor at the Institut Catholique de Paris, where he gave a course in Arabic language and literature, as well as a course in Islamology at the chair of History of Religions. He was forced to resign this post in 1964 due to a cancer. He retired to his convent and led a secluded life. He did, however write a report on the current state of Islam for the bishops of France at the Second Vatican Council. He was received by Pope Paul VI in 1966.Benediction (The) ◊ The title that Brother Bruno has given to the seven verses of the first Sūrah.

Berākhāh ◊ The invocation to the name of God, traditionally called basmala.

Biella (Joan Copeland) ◊ American researcher (1947-....) Member of the W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research, Jerusalem (1982). She authored the Dictionary of Old South Arabic: Sabaean dialect.

Blachère (Régis) ◊ French orientalist, Arabist and translator of the Qurʾān (1900-1973). He held the Arab Philosophy Chair at the Sorbonne and was the director of the Institute of Islamic Studies (Institut des études islamiques) in Paris. He published a history of Arabic literature (1952), a study on the problem posed by Muḥammad (1952), a translation of the Qurʾān (1950 and a new version in 1957), and an introduction to the Qurʾān (1959). He also co-authored a grammar of classical Arabic with Gaudefroy-Demombynes. Throughout his analysis, Brother Bruno refers to Régis Blachère’s translation of the Qurʾān, along with Denise Masson’s, for they are the only recent translators who show some concern for critical methods. Blachère and Masson will only serve Brother Bruno occasionally to emphasise the inconsistencies and contradictions of the “accepted meaning.” He does not systematically compare his exegesis with theirs. You will come to understand how totally pointless this would be as you advance in Brother Bruno’s commentary.

Blachère (Régis) ◊ French orientalist, Arabist and translator of the Qurʾān (1900-1973). He held the Arab Philosophy Chair at the Sorbonne and was the director of the Institute of Islamic Studies (Institut des études islamiques) in Paris. He published a history of Arabic literature (1952), a study on the problem posed by Muḥammad (1952), a translation of the Qurʾān (1950 and a new version in 1957), and an introduction to the Qurʾān (1959). He also co-authored a grammar of classical Arabic with Gaudefroy-Demombynes. Throughout his analysis, Brother Bruno refers to Régis Blachère’s translation of the Qurʾān, along with Denise Masson’s, for they are the only recent translators who show some concern for critical methods. Blachère and Masson will only serve Brother Bruno occasionally to emphasise the inconsistencies and contradictions of the “accepted meaning.” He does not systematically compare his exegesis with theirs. You will come to understand how totally pointless this would be as you advance in Brother Bruno’s commentary.- C

Caetani (Leone) ◊ Italian orientalist, historian and Member of Parliament (1869-1935). Leone Caetani was born into the ancient aristocratic family of Rome. He studied classical history at La Sapienza University, presenting in 1891, a thesis on a papal legation in Paris. However, he became fascinated with the Orient at an early age and made a number of journeys there. His most important journey took place in 1894 from Egypt to Persia. At La Sapienza, he also attended courses in Arabic language and literature, and in Semitic languages. He soon mastered several oriental languages, including Arabic, Turkish and Persian. He participated in his first international congress of orientalists in London in September 1892. Thanks to the family fortune, he was able to build up a rich library on Arab-Muslim civilisation, including a remarkable collection of photographs of manuscripts.

Caetani (Leone) ◊ Italian orientalist, historian and Member of Parliament (1869-1935). Leone Caetani was born into the ancient aristocratic family of Rome. He studied classical history at La Sapienza University, presenting in 1891, a thesis on a papal legation in Paris. However, he became fascinated with the Orient at an early age and made a number of journeys there. His most important journey took place in 1894 from Egypt to Persia. At La Sapienza, he also attended courses in Arabic language and literature, and in Semitic languages. He soon mastered several oriental languages, including Arabic, Turkish and Persian. He participated in his first international congress of orientalists in London in September 1892. Thanks to the family fortune, he was able to build up a rich library on Arab-Muslim civilisation, including a remarkable collection of photographs of manuscripts.

He also conceived very early on what was to become his magnum opus: a meticulous analytical history, year by year, of the early days of Islam from the Hijrah in 622 to the death of the Caliph Ali ibn Abi Talib in 661 (year 40 of the Hijrah). Caetani collected as exhaustively as possible all the “historical” material transmitted by ancient authors, and treated it by the critical methods of modern science. The result was the Annali dell’ Islam, a monumental ten volume work, published between 1905 and 1926. Caetani conceived and began this great work alone, but later enlisted the help of collaborators.

In 1919 he became a full member of the Academy of the Lynceans (of which he had been a correspondent since 1911), but he did not really return to his work on the Annali dell’ Islam, which he had planned to continue until the fall of the Umayyads in 750. In 1924 he created a Fondazione Caetani per gli studi musulmani at the Academy of the Lynceans, to which he bequeathed his splendid orientalist library, and of which he had initially planned to become active president. His notorious opposition to fascism led him to leave Italy for Canada in 1927. He acquired a property in Vernon in the Vancouver hinterland, where he led a secluded and rustic life, interspersed with brief stays in France and England. Having adopted Canadian citizenship, he was stripped of his Italian nationality by the Fascist regime in April 1935, and thereby disbarred from the Academy of the Lynceans a few months before his death. Cazelles (Henri) ◊ Sulpician, Doctor of Law and of Theology (1912-2008). He was ordained priest in 1940 and entered the Society of Saint Sulpice in 1944. He began his teaching career at the Sulpician seminary of Issy-les-Moulineaux. There his most famous student, Father Georges de Nantes, said of him: “He was, and still is today, a well of erudition, an ocean.” Besides Greek and Hebrew, Father Cazelles knew the ancient Egyptian, Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian and Hittite languages, as well as classical Arabic. In 1954, he was offered the Chair of the Old Testament at the Faculty of Theology of the Institut catholique de Paris. This is where Brother Bruno attended Father Cazelles Biblical Hebrew courses (1956-1965).

Cazelles (Henri) ◊ Sulpician, Doctor of Law and of Theology (1912-2008). He was ordained priest in 1940 and entered the Society of Saint Sulpice in 1944. He began his teaching career at the Sulpician seminary of Issy-les-Moulineaux. There his most famous student, Father Georges de Nantes, said of him: “He was, and still is today, a well of erudition, an ocean.” Besides Greek and Hebrew, Father Cazelles knew the ancient Egyptian, Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian and Hittite languages, as well as classical Arabic. In 1954, he was offered the Chair of the Old Testament at the Faculty of Theology of the Institut catholique de Paris. This is where Brother Bruno attended Father Cazelles Biblical Hebrew courses (1956-1965).Centre national de la recherche scientifique ◊ = National Organisation for Scientific Research. The CNRS is a multidisciplinary research organisation, established by the French government in 1941 and affiliated to the Ministry of Education. It receives state funding and its members, who are highly qualified specialists in their fields, are engaged in research in the areas of science, engineering, humanities and social sciences.

CNRS ◊ see Centre national de la recherche scientifique

Constantius II (Flavius Julius Constantius) ◊ Roman emperor from 337 to 361 (317-361). Constantius was a son of Constantine the Great, who elevated him to the imperial rank of caesar in 324 and after whose death Constantius became augustus together with his brothers, Constantine II and Constans in 337. The brothers divided the empire among themselves, with Constantius receiving Greece, Thrace, the Asian provinces and Egypt in the east. In 353, Constantius became the sole ruler of the empire after the death of his brothers during civil wars and usurpations. His reign saw constant warfare on the borders against the Persian Sassanian Empire and Germanic peoples. His religious policies inflamed domestic conflicts that would continue after his death. Constantius banned pagan sacrifices by closing their temples. During his reign he attempted to mould the Christian Church to follow his compromise Semi-Arian position, convening several councils. The most notable of these were the Council of Rimini (359) and Seleucia (360) which, however, were not reckoned ecumenical. Constantius is not remembered as a restorer of unity, but as a heretic who arbitrarily imposed his will on the Church.

Constantius II (Flavius Julius Constantius) ◊ Roman emperor from 337 to 361 (317-361). Constantius was a son of Constantine the Great, who elevated him to the imperial rank of caesar in 324 and after whose death Constantius became augustus together with his brothers, Constantine II and Constans in 337. The brothers divided the empire among themselves, with Constantius receiving Greece, Thrace, the Asian provinces and Egypt in the east. In 353, Constantius became the sole ruler of the empire after the death of his brothers during civil wars and usurpations. His reign saw constant warfare on the borders against the Persian Sassanian Empire and Germanic peoples. His religious policies inflamed domestic conflicts that would continue after his death. Constantius banned pagan sacrifices by closing their temples. During his reign he attempted to mould the Christian Church to follow his compromise Semi-Arian position, convening several councils. The most notable of these were the Council of Rimini (359) and Seleucia (360) which, however, were not reckoned ecumenical. Constantius is not remembered as a restorer of unity, but as a heretic who arbitrarily imposed his will on the Church.

Constantius realising that he could not possibly handle all too threats faced by the Empire, elevated Julian, his last remaining male relative, to the rank of caesar in 355. In 360, however, Julian claimed the rank of augustus, leading to war between the two after Constantius’ attempts to persuade Julian to resign the title of augustus and be satisfied with that of caesar failed. At the time Constantius was in the East dealing with a new Sassanid threat. A temporary respite in hostilities allowed Constantius to turn his full attention to facing Julian. Constantius gathered his forces and set off west. However, by the time he reached Mopsuestia in Cilicia, it was clear that he was fatally ill and would not survive to face Julian. Realising his death was near, Constantius had himself baptised by Euzoius, the Semi-Arian bishop of Antioch, and then declared that Julian was his rightful successor. Constantius II died of fever on November 3, 361.- D

Dalman (Gustaf Hermann) ◊ German Lutheran theologian, philologist and orientalist (1855-1941). Born Gustaf Armin Marx, he did extensive field work in Palestine before the First World War, collecting inscriptions, poetry, and proverbs. He also collected physical articles illustrating the life of the indigenous farmers and herders of the country. He pioneered the study of biblical and early post-biblical Aramaic, publishing an authoritative grammar (1894) and dictionary (1901), as well as other works. The theologian and translator Franz Delitzsch, who translated the New Testament into Hebrew, entrusted to Dalman the work of revising the Hebrew text.

Dalman (Gustaf Hermann) ◊ German Lutheran theologian, philologist and orientalist (1855-1941). Born Gustaf Armin Marx, he did extensive field work in Palestine before the First World War, collecting inscriptions, poetry, and proverbs. He also collected physical articles illustrating the life of the indigenous farmers and herders of the country. He pioneered the study of biblical and early post-biblical Aramaic, publishing an authoritative grammar (1894) and dictionary (1901), as well as other works. The theologian and translator Franz Delitzsch, who translated the New Testament into Hebrew, entrusted to Dalman the work of revising the Hebrew text. Daniélou (Jean) ◊ French Jesuit priest, renowned theologian (1905-1974). He was created cardinal by Paul VI in 1970. Son of an anticlerical politician and a foundress of Catholic educational institutions for girls, Jean Daniélou studied literature and philosophy at the Sorbonne. In 1929, he entered the Jesuits and devoted his life to teaching. After studying theology at the Catholic Faculty of Lyon, he was ordained priest in 1938. He founded the collection “Sources chrétiennes” in collaboration with Henri de Lubac. After reading Brother Bruno’s scientific dissertations on the results of his historical research on pre-Islamic Arabia and on the Arab Conquest, he encouraged him to publish them.

Daniélou (Jean) ◊ French Jesuit priest, renowned theologian (1905-1974). He was created cardinal by Paul VI in 1970. Son of an anticlerical politician and a foundress of Catholic educational institutions for girls, Jean Daniélou studied literature and philosophy at the Sorbonne. In 1929, he entered the Jesuits and devoted his life to teaching. After studying theology at the Catholic Faculty of Lyon, he was ordained priest in 1938. He founded the collection “Sources chrétiennes” in collaboration with Henri de Lubac. After reading Brother Bruno’s scientific dissertations on the results of his historical research on pre-Islamic Arabia and on the Arab Conquest, he encouraged him to publish them. de Sola Pool (David) ◊ Jewish scholar, author, and civic leader (1885-1970). He was the chief Sephardic rabbi in the United States and a recognised world leader of Judaism. He studied at the University of London. He held a doctorate in ancient languages from the University of Heidelberg. Born in London, de Sola Pool was invited in 1907 to become the rabbi of the oldest Jewish congregation in the United States, located in New York City. His book The Kaddish (1909) remains a definitive and well-regarded work on the origins of the Kaddish prayer.

de Sola Pool (David) ◊ Jewish scholar, author, and civic leader (1885-1970). He was the chief Sephardic rabbi in the United States and a recognised world leader of Judaism. He studied at the University of London. He held a doctorate in ancient languages from the University of Heidelberg. Born in London, de Sola Pool was invited in 1907 to become the rabbi of the oldest Jewish congregation in the United States, located in New York City. His book The Kaddish (1909) remains a definitive and well-regarded work on the origins of the Kaddish prayer.Demombynes – see Gaudefroy-Demombynes

Dussaud (René) ◊ Orientalist, archaeologist (1868-1958). Professor of Anthropology, curator at the department of oriental antiquities at the Louvre Museum, teacher at the Collège de France. An engineer by training, he quickly turned to the study of the Near East by following the teaching of Charles Clermont-Ganneau, holder of the chair on epigraphy and Semitic antiquities at the Collège de France. Clermont-Ganneau encouraged him to undertake trips which, from 1895 to 1901, led him to visit the whole of Lebanon and western Syria. From his explorations, he brought back copies of numerous Nabataean, Greek and Latin inscriptions, materials for his works in collaboration with Frédéric Macler and the basis for his monumental work on the historical topography of Syria (1927). He also brought back photographs that were among the first to have been taken in interior Syria. Dussaud’s interest in the pre-Islamic Arab world continued throughout his life. He was also one of the first to analyse the different civilisations of the eastern Mediterranean in the 2nd millennium and to recognise their affinities.

Dussaud (René) ◊ Orientalist, archaeologist (1868-1958). Professor of Anthropology, curator at the department of oriental antiquities at the Louvre Museum, teacher at the Collège de France. An engineer by training, he quickly turned to the study of the Near East by following the teaching of Charles Clermont-Ganneau, holder of the chair on epigraphy and Semitic antiquities at the Collège de France. Clermont-Ganneau encouraged him to undertake trips which, from 1895 to 1901, led him to visit the whole of Lebanon and western Syria. From his explorations, he brought back copies of numerous Nabataean, Greek and Latin inscriptions, materials for his works in collaboration with Frédéric Macler and the basis for his monumental work on the historical topography of Syria (1927). He also brought back photographs that were among the first to have been taken in interior Syria. Dussaud’s interest in the pre-Islamic Arab world continued throughout his life. He was also one of the first to analyse the different civilisations of the eastern Mediterranean in the 2nd millennium and to recognise their affinities.

He played a decisive role in the creation of an antiquities service in the countries of the Levant placed under the mandate of France after the First World War; he encouraged the opening of major excavation sites and followed their development and publication. For example, the discovery, in 1929, of a library of clay tablets at Ras Shamrah (on the northern Syrian coast), containing texts in the Mesopotamian language, Akkadian, deciphered since the 19th century, and others written in an alphabetical script in a language then unknown. These tablets from this 2nd millennium site revealed the ancient name of the city, Ugarit; thousands of administrative, legal, historical, ritual and mythological texts gave voice to the Levantine civilisations that were known only through the Bible and the Homeric poems. Dussaud established the relationship between the intellectual culture of Ugarit and that of the Old Testament.- E

Ezana of Axum ◊ First Christian ruler of the Kingdom of Axum (c. 320-c. 360 a.d.). ʿEzana of Axum (other possible transliterations: Aeizanes, Aezana or Aizan) was ruler of the Kingdom of Axum (c. 325-c. 356 a.d.) an ancient kingdom centred in what is now northern Ethiopia and Eritrea. Although the name ʿEzana is unknown in the King Lists of Axum, it is attested on coins and in the inscriptions on several stelae and obelisks that he had erected to record his military campaigns. A well-known inscription presents him, as “king of the Axumites and of the Ḥimyarites and of Ḏū Raydān and of the Ethiopians and of the Sabaeans,” indicating that at the time of his reign the Axum Empire extended over a large part of the southern Arabian peninsula.

ʿEzana’s education was entrusted by the widowed queen, his mother, to one of his father’s former slaves, the Syrian Christian Frumentius (see article in Glossary). ʿEzana thus became the first monarch of the Kingdom of Axum to embrace Christianity. When the prince came of age, Frumentius travelled to Alexandria, Egypt, where he requested Saint Athanasius, Patriarch of Alexandria, to send a bishop and some priests as missionaries to Axum to help in the conversion of the kingdom. Saint Athanasius found no one better than Frumentius himself, so he consecrated him as the first bishop of Axum. ʿEzana’s conversion is attested in two inscriptions, the earlier one refers to him adoring pagan gods, in the later one he is said to worship the “God of Heaven.” It is also attested by numismatics. During ʿEzana’s reign the pagan motif with disc and crescent on Axumite coins was replaced by the cross and a motto in Greek “May this please the people,” which expresses the sovereigns concern for his subjects.- F

Fakhry (Ahmad) ◊ Egyptian archaeologist (1905–1973). He worked mainly in the Western desert of Egypt (including in 1940 the excavation at El Haiz, and then at Siwa), and also in the necropolis at Dahshur.

Fakhry (Ahmad) ◊ Egyptian archaeologist (1905–1973). He worked mainly in the Western desert of Egypt (including in 1940 the excavation at El Haiz, and then at Siwa), and also in the necropolis at Dahshur.Février (James Germain) ◊ French historian and philologist (1895-1976). Février was a specialist of the Semitic world, his thesis was on the archaeological site of Palmyra and he did much work on the history of Carthage and the Phoenicians. He was Study Director at the École pratique des hautes études.

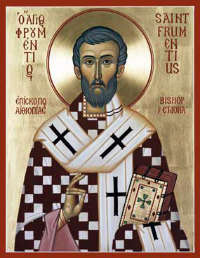

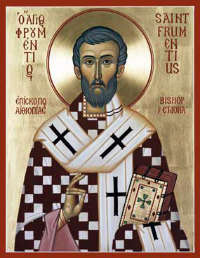

Frumentius ◊ Catholic missionary and the first bishop of Axum [present-day Ethiopia] (died c. 383). Frumentius was a Syro-Phoenician Greek born in Tyre [present-day Lebanon]. According to an account given by Frumentius’ brother Edesius, the two boys, while accompanying an uncle on a voyage to Ethiopia, after the local people at one of the harbours of the Red Sea where their ship stopped had massacred all those aboard, sparing only the two boys, they were taken as slaves to the King of Axum. Frumentius and Edesius soon gained the favour of the king, who raised them to positions of trust. Shortly before his death, the king freed them. The widowed queen, however, prevailed upon them to remain at the court and assist her in the education of the young heir, ʿEzana, and in the administration of the kingdom during the prince’s minority. They remained and used their influence to spread Christianity. First they encouraged the Christian merchants present in the country to practise their faith openly.

Frumentius ◊ Catholic missionary and the first bishop of Axum [present-day Ethiopia] (died c. 383). Frumentius was a Syro-Phoenician Greek born in Tyre [present-day Lebanon]. According to an account given by Frumentius’ brother Edesius, the two boys, while accompanying an uncle on a voyage to Ethiopia, after the local people at one of the harbours of the Red Sea where their ship stopped had massacred all those aboard, sparing only the two boys, they were taken as slaves to the King of Axum. Frumentius and Edesius soon gained the favour of the king, who raised them to positions of trust. Shortly before his death, the king freed them. The widowed queen, however, prevailed upon them to remain at the court and assist her in the education of the young heir, ʿEzana, and in the administration of the kingdom during the prince’s minority. They remained and used their influence to spread Christianity. First they encouraged the Christian merchants present in the country to practise their faith openly.

When the prince came of age, Frumentius travelled to Alexandria, Egypt, where he requested Athanasius, Patriarch of Alexandria, to send a bishop and some priests as missionaries to Axum. By Athanasius’ own account, he believed Frumentius to be the most suitable person for the mission and consecrated him as bishop. Frumentius returned to Ethiopia, where he erected his episcopal see at Axum, then converted and baptised King ʿEzana, who built many churches and spread Christianity throughout Ethiopia. Frumentius established the first monastery of Ethiopia. In about 356, the Emperor Constantius II wrote to King ʿEzana and his brother Saizana, requesting them to replace Frumentius as bishop with Theophilus of Dibus, dubbed “the Indian,” who supported the Arian position, as did the emperor. Frumentius had been appointed by Athanasius, a leading opponent of Arianism. The king refused the request. Ethiopian traditions credit Frumentius with the first Ge’ez translation of the New Testament.- G

Gaudefroy-Demombynes (Maurice) ◊ French Arabist, specialist in Islam and the history of religions (1862–1957). He was a professor at the École nationale des langues orientales vivantes (today INALCO). His best known works are his historical and religious studies on the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca and Muslim institutions. He also translated into French in an annotated edition the story of the Arab travel writer and explorer Ibn Jubair (1145–1217). His book written after Arab authors on Syria at the time of the Mamluk is also a seminal work. Gaudefroy-Demombynes clearly realised that two extreme attitudes were possible for European scholars: either to accept the Sīrah, the only documentary material available to them, as it had been put together in the Muslim world through the evolutions of the Tradition and piety or to accept “only those things, the veracity of which could be established, that is to say, almost nothing.” Unfortunately, Gaudefroy-Demombynes adopted the first solution, even if it meant “appearing naïve in the eyes of certain people.” In order to justify his choice, he had to play down the significance of Father Lammens’ criticism of the Sīrah.

Gaudefroy-Demombynes (Maurice) ◊ French Arabist, specialist in Islam and the history of religions (1862–1957). He was a professor at the École nationale des langues orientales vivantes (today INALCO). His best known works are his historical and religious studies on the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca and Muslim institutions. He also translated into French in an annotated edition the story of the Arab travel writer and explorer Ibn Jubair (1145–1217). His book written after Arab authors on Syria at the time of the Mamluk is also a seminal work. Gaudefroy-Demombynes clearly realised that two extreme attitudes were possible for European scholars: either to accept the Sīrah, the only documentary material available to them, as it had been put together in the Muslim world through the evolutions of the Tradition and piety or to accept “only those things, the veracity of which could be established, that is to say, almost nothing.” Unfortunately, Gaudefroy-Demombynes adopted the first solution, even if it meant “appearing naïve in the eyes of certain people.” In order to justify his choice, he had to play down the significance of Father Lammens’ criticism of the Sīrah. Gesenius (Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm) ◊ German Hebrew philologist and orientalist (1786-1842). He pioneered the comparative method in the analysis of Chaldean, Hebrew and Aramaic. As he was steeped in rationalism, he abandoned the religious considerations that had prevailed until then in the study of the Semitic languages. Among other things, he wrote a Hebrew Grammar (Lexicon hebraïcum et chaldaïcum, edit. Leipzig, 1847) and a commented translation of the Book of Isaiah. His Hebrew-German lexicon served as the basis for the Brown-Driver-Briggs dictionary.

Gesenius (Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm) ◊ German Hebrew philologist and orientalist (1786-1842). He pioneered the comparative method in the analysis of Chaldean, Hebrew and Aramaic. As he was steeped in rationalism, he abandoned the religious considerations that had prevailed until then in the study of the Semitic languages. Among other things, he wrote a Hebrew Grammar (Lexicon hebraïcum et chaldaïcum, edit. Leipzig, 1847) and a commented translation of the Book of Isaiah. His Hebrew-German lexicon served as the basis for the Brown-Driver-Briggs dictionary. Glaser (Eduard) ◊ Jewish Austrian Arabist and archaeologist (1855-1908). He is considered the most important scholar to have studied Yemen being one of the first Europeans to explore South Arabia. He collected thousands of inscriptions in Yemen.

Glaser (Eduard) ◊ Jewish Austrian Arabist and archaeologist (1855-1908). He is considered the most important scholar to have studied Yemen being one of the first Europeans to explore South Arabia. He collected thousands of inscriptions in Yemen.

While working as a private tutor in Prague, Glaser began studying mathematics, physics, astronomy, geology, geography, geodesy and Arabic at the Polytechnic in Prague until 1875. Glaser successfully concluded his studies in Arabic, in Vienna, and enrolled thereafter in an astronomy class. An important turning point in his academic education came in 1880, when Glaser enrolled in the classes of David Heinrich Müller, the founder of South Arabian studies in Austria, for the study of Sabaean grammar. Müller suggested to him that he travel to Yemen, for the purpose of copying down Sabaean inscriptions. A scholarship from the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres in Paris enabled him to make his first trip to Yemen (1882-1884). He returned there on three other occasions (1885-1886, 1887-1888, and 1892-1894).

In addition to his knowledge of Latin, Greek and most of the major European languages, Glaser was proficient in both classical and colloquial Arabic. He saw Yemen as the ideal place for finding basic similarities between the rites of the indigenous peoples and those of the ancient Israelites. He also hoped to identify the geographical names mentioned in the Bible. Glaser was an expert in the Sabaean scripts. Furthermore, his knowledge of Abyssinian history and its language propelled him to examine the connexions between Abyssinia (present-day Ethiopia) and Yemen in ancient times.

Glaser’s good relations with the Turkish governors of Yemen, allowed him to realise his scientific plans and endeavours. He was able to travel throughout many areas inaccessible to foreigners and was thereby able to copy down hundreds of inscriptions, both in Sabaic and in Arabic.

Unlike Joseph Halévy, who concentrated only on the Yemen’s past, Glaser observed and documented everything he saw in Yemen. He carried out research on the topography, the geology and geography, prepared cartographic maps, took astronomical notes and collected data on meteorology, climate and economic trade, as well as on the nation’s crafts.

From 1895 until his death, Glaser lived in Munich. He dedicated most of his time to preparing his scientific material for publication. Despite his great contribution to science Glaser never succeeded in acquiring a suitable academic position and he remained an outsider in the academic circles of Austria, Germany and France. Only about half of Glaser’s 990 copies and imprints of Sabaean inscriptions have been published, and only a small portion of his 17 volumes of diaries, 24 manuscripts and his scientific findings have been studied. Goeje (Michael Jan de) ◊ German-speaking Dutch Orientalist (1836-1909). From 1854 to 1858, Goeje studied theology and Oriental languages at the University of Leiden, and became particularly proficient in Arabic. After taking his Doctorate of Letters there in 1860, he did postdoctoral studies at the University of Oxford, where he collated the Bodleian Library manuscripts of the important medieval Arabic geographer Al-Idrīsī. In 1883, he became a professor of Arabic at Leiden until his retirement in 1906.

Goeje (Michael Jan de) ◊ German-speaking Dutch Orientalist (1836-1909). From 1854 to 1858, Goeje studied theology and Oriental languages at the University of Leiden, and became particularly proficient in Arabic. After taking his Doctorate of Letters there in 1860, he did postdoctoral studies at the University of Oxford, where he collated the Bodleian Library manuscripts of the important medieval Arabic geographer Al-Idrīsī. In 1883, he became a professor of Arabic at Leiden until his retirement in 1906.

Goeje exerted great influence not only on his students, but also on the theologians and eastern administrators who attended his lectures. In 1886, he became Foreign correspondent of the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres. He headed the International Congress of Orientalists in Algiers in 1905. He was a member of the Institut de France, was awarded the German Order of Merit, and received an honorary doctorate from Cambridge University. At the time of his death, he was President of the newly formed International Association of Academies of Science. He became a member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1869.

During his career, Goeje edited many Arabic works, the most important of which was the 13-volume medieval history Annals of Tabari (1879–1901). He was also chief editor of the first three volumes of the Encyclopaedia of Islam (1908). His numerous editions of Arabic texts are still of great value to scholars today. Goldziher (Ignác) ◊ Jewish Hungarian orientalist (1850-1921). He is considered one of the founders of modern Islamic studies in Europe. Goldziher’s major work is his careful investigation of pre-Islamic and Islamic law, Muhammedanische Studien published in 1890. In it, he showed how the ḥadīṯs reflect the legal and doctrinal controversies of the two centuries after the death of Muḥammad rather than the words of Muḥammad himself. The Jesuit scholar, Father Lammens, based his own works on these “insightful studies of Professor Goldziher” who had thus brought to light “the profoundly tendentious nature of the [Muslim] Tradition.” Goldziler’s diary has been published in German under the title Tagebuch. In it, we find surprising reflections concerning his journey through the Middle East in 1873: “In those weeks, I truly entered into the spirit of Islam to such an extent that ultimately I became inwardly convinced that I myself was a Muslim, and judiciously discovered that this was the only religion which, even in its doctrinal and official formulation, can satisfy philosophic minds. My ideal was to elevate Judaism to a similar rational level. Islam, as my experience taught me, is the only religion, in which superstitious and heathen ingredients are not frowned upon by rationalism, but by orthodox doctrine.” In Cairo, Goldziher even went so far as to pray as a Muslim: “In the midst of the thousands of the pious, I rubbed my forehead against the floor of the mosque. Never in my life was I more devout, more truly devout, than on that exalted Friday.” Despite this, Goldziher remained a devout Jew all his life.

Goldziher (Ignác) ◊ Jewish Hungarian orientalist (1850-1921). He is considered one of the founders of modern Islamic studies in Europe. Goldziher’s major work is his careful investigation of pre-Islamic and Islamic law, Muhammedanische Studien published in 1890. In it, he showed how the ḥadīṯs reflect the legal and doctrinal controversies of the two centuries after the death of Muḥammad rather than the words of Muḥammad himself. The Jesuit scholar, Father Lammens, based his own works on these “insightful studies of Professor Goldziher” who had thus brought to light “the profoundly tendentious nature of the [Muslim] Tradition.” Goldziler’s diary has been published in German under the title Tagebuch. In it, we find surprising reflections concerning his journey through the Middle East in 1873: “In those weeks, I truly entered into the spirit of Islam to such an extent that ultimately I became inwardly convinced that I myself was a Muslim, and judiciously discovered that this was the only religion which, even in its doctrinal and official formulation, can satisfy philosophic minds. My ideal was to elevate Judaism to a similar rational level. Islam, as my experience taught me, is the only religion, in which superstitious and heathen ingredients are not frowned upon by rationalism, but by orthodox doctrine.” In Cairo, Goldziher even went so far as to pray as a Muslim: “In the midst of the thousands of the pious, I rubbed my forehead against the floor of the mosque. Never in my life was I more devout, more truly devout, than on that exalted Friday.” Despite this, Goldziher remained a devout Jew all his life. Grosjean (Jean) ◊ French poet, writer and translator (1912-2006). In 1933 he entered the Saint-Sulpice Seminary. After his military service in Lebanon (1936-37,) he was ordained a priest. Mobilised and made prisoner during World War II, his first poetry book was published the year after the war. In 1950, he abandoned the priesthood and married. His translation of the Qurʾān was published in 1979. Brother Bruno considers it a notable regression because he totally disregards the historical and critical method. Brother Bruno is therefore astonished by the approval his translation received from the Islamic Research Institute of Al-Azhar.

Grosjean (Jean) ◊ French poet, writer and translator (1912-2006). In 1933 he entered the Saint-Sulpice Seminary. After his military service in Lebanon (1936-37,) he was ordained a priest. Mobilised and made prisoner during World War II, his first poetry book was published the year after the war. In 1950, he abandoned the priesthood and married. His translation of the Qurʾān was published in 1979. Brother Bruno considers it a notable regression because he totally disregards the historical and critical method. Brother Bruno is therefore astonished by the approval his translation received from the Islamic Research Institute of Al-Azhar.Guarded Tablet ◊ According to the Islamic tradition, the Qurʾān was passed on to Muḥammad, such as it is kept in heaven from all eternity, on the Guarded Tablet (Q 85:22), the heavenly architype, revealed by ʾAllāh, in the precise, literal form that has been passed down to the present day.

- H

Ḥadīṯ (ḥadīṯ) ◊ The ḥadīṯ (lower-case ḥ) are the narrative records of what are purported to be the sayings or customs of Muḥammad and his companions. The Ḥadīṯ (upper-case Ḥ) is the collective body of the ḥadīṯ. Father Lammens positively demonstrates that the ḥadīṯ are nothing but pure inventions embroidered on the framework of the Qurʾānic text. The Ḥadīṯ elaborates its legends, merely inventing names for the actors depicted therein and spinning out the primitive theme.

Halévy (Joseph) ◊ Naturalised French Jewish orientalist (1827-1917) born in Edirne (Ottoman Empire). In 1867-1868 Joseph Halévy was entrusted with a research mission to Ethiopia by the Alliance Israélite Universelle. On this occasion, he was the first Western Jew to come into contact with the Falashas, a community of Ethiopian Jews, and to have brought back a detailed description of their way of life.

Halévy (Joseph) ◊ Naturalised French Jewish orientalist (1827-1917) born in Edirne (Ottoman Empire). In 1867-1868 Joseph Halévy was entrusted with a research mission to Ethiopia by the Alliance Israélite Universelle. On this occasion, he was the first Western Jew to come into contact with the Falashas, a community of Ethiopian Jews, and to have brought back a detailed description of their way of life.

Linguist, archaeologist and geographer, Halévy was a professor of Ethiopian and Sabean languages at the École pratique des hautes études in Paris (1879-1917). He founded the Semetic and Ancient History Review. His most important work was carried out in Yemen for the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres. He travelled throughout this country in 1869 and 1870 in search of the Sabean inscriptions. The result was a survey of 800 inscriptions of which 686 are in Sabaic, which allowed a first approach to this ancient civilisation. He was the first to propose a partial deciphering of the Sabean language.

In the specifically Jewish field, the most remarkable of Halevy’s works is to be read in his ‘Biblical Research.’ In it he analyses the first twenty-five chapters of Genesis in the light of the recently discovered Assyro-Babylonian documents, and he believed that he had found therein an old Semitic myth almost completely Assyro-Babylonian, though considerably transformed by the spirit of prophetic monotheism. However, the narratives of Abraham and his descendants were considered by him to be fundamentally historical, though considerably embellished, and the work of a single author. Halévy’s scientific activity was very diverse, and his writings on oriental philology and archaeology earned him a worldwide reputation.Hapax legomenon ◊ A word or form occurring only once in a document or corpus.

Henninger (Joseph) ◊ German orientalist and Catholic priest, member of the Steyler missionaries [Divine Word Society (SVD)] (1906-1991). After having completed his theological studies at the Pontificia Universitas Gregoriana in Rome in 1934, he went to Vienna, where he attended lectures on Ethnology, Prehistory and Physical Anthropology. In 1934 Henninger became a member of the Anthropos Institute, and he became the assistant editor of its journal in 1936, a position he held until 1949. When Austria became part of the Third Reich in 1938, the Anthropos Institute and its journal moved to Fribourg, Switzerland. He began lecturing at the University in Fribourg and became professor there in 1954. He became associate professor at the University in Bonn in 1964. Ten years later, Henninger took up a professorship at the Philosophical-Theological Faculty in St. Augustin, where he lectured throughout the following years. The regional focus of his work lay on Arabian countries in Northern and Eastern Africa, while the field of his interest included Semitic cultures as well as theories on sacrifice and research on Islam.

Henninger (Joseph) ◊ German orientalist and Catholic priest, member of the Steyler missionaries [Divine Word Society (SVD)] (1906-1991). After having completed his theological studies at the Pontificia Universitas Gregoriana in Rome in 1934, he went to Vienna, where he attended lectures on Ethnology, Prehistory and Physical Anthropology. In 1934 Henninger became a member of the Anthropos Institute, and he became the assistant editor of its journal in 1936, a position he held until 1949. When Austria became part of the Third Reich in 1938, the Anthropos Institute and its journal moved to Fribourg, Switzerland. He began lecturing at the University in Fribourg and became professor there in 1954. He became associate professor at the University in Bonn in 1964. Ten years later, Henninger took up a professorship at the Philosophical-Theological Faculty in St. Augustin, where he lectured throughout the following years. The regional focus of his work lay on Arabian countries in Northern and Eastern Africa, while the field of his interest included Semitic cultures as well as theories on sacrifice and research on Islam.Hijrah ◊ The Hijrah, “emigration,” is the purported flight of Muḥammad and his faithful followers from Mecca to Medina in 622. This year is traditionally given as the date of Islam’s birth.

Hirschberg (Joachim Wilhelm) ◊ Israeli specialist of the history of the Jews in Islamic countries. (1903-1976) Born in Tarnopol (administered at that time by the Austro-Hungarian Empire), he studied in Vienna at the University and the Rabbinical Seminary. From 1927 to 1939, he was rabbi in Czestochowa, then in 1943, he emigrated to Palestine. He was a research fellow at the Hebrew University from 1947 to 1956 and from 1960 was professor of history at Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan, where he headed the Institute for Research on the History of the Jews in Eastern Countries. Hirschberg wrote extensively on the history of Jews in Islamic lands, his major work being a two-volume history of the Jews in North Africa.

Hirschfeld (Hartwig) ◊ Jewish, Prussian-born, British orientalist, bibliographer, and educator (1854-1934). Hirschfeld studied Oriental languages and philosophy and the University of Berlin. He received his doctorate from the University of Strasburg in 1878. He obtained a travelling scholarship in 1882 which enabled him to study Arabic and Hebrew at Paris. Hirschfeld immigrated to England in 1889, where he became professor of Biblical exegesis, Semitic languages, and philosophy at the Montefiore College. In 1901, he was invited to examine the Arabic fragments in the Taylor-Schechter collection. That same year, he was appointed librarian and professor of Semitic languages at Jews’ College, a position he occupied until 1929. At the same time, he became a lecturer in Semitic epigraphy at University College London in 1903, a lecturer in Ethiopic in 1906, and full professor and Goldsmid Lecturer in Hebrew there in 1924. His particular scholarly interest lay in Arabic Jewish literature and in the relationship between Jewish and Arab cultures. He is best known for his editions of Judah Halevi’s Kuzari, which he published in its original Judeo-Arabic and his studies on the Cairo Geniza. Hirschfeld also contributed articles to numerous periodicals.

Homeritae ◊ Term used by classical authors to designate the Ḥimyarites, the inhabitants of the Kingdom of Ḥimyar.

Horovitz (Josef) ◊ German Orientalist (1874-1931). This son of a prominent orthodox rabbi was educated in Frankfurt and later studied at the University of Berlin with Edward Sachau, where he also began to teach. In 1905-1906, he travelled through Turkey, Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, on commission to find Arabic manuscripts. From 1907 to 1914, he lived in India, where he taught Arabic at the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College in Aligar. He also served as the curator of Islamic inscriptions for the Indian government. Due to his German nationality, he lost these positions at the beginning of the First World War.

Horovitz (Josef) ◊ German Orientalist (1874-1931). This son of a prominent orthodox rabbi was educated in Frankfurt and later studied at the University of Berlin with Edward Sachau, where he also began to teach. In 1905-1906, he travelled through Turkey, Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, on commission to find Arabic manuscripts. From 1907 to 1914, he lived in India, where he taught Arabic at the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College in Aligar. He also served as the curator of Islamic inscriptions for the Indian government. Due to his German nationality, he lost these positions at the beginning of the First World War.

In 1914, he was appointed to profess Semitic languages at the University of Frankfurt, where he would teach until his death. His range included early Islamic history, early Arabic poetry, Qur’anic studies, and Islam in India. Horovitz produced an amazing number of outstanding students during his rather brief tenure at Frankfurt, and his influence upon all of them was strong. He was a very reserved man, but when set talking he was an inexhaustible source of knowledge about the East, past and present, and a paragon of philological exactitude. In the 1920s, as a member of the board of trustees of Hebrew University in Jerusalem from its inception, Horovitz created the department of Oriental studies, became its director in absentia, and initiated its collective project, the concordance of early Arabic poetry. At first Horovitz devoted himself to the study of Arabic historical literature and then to early Arabic poetry. His major work was a commentary on the Qurʾān, which he did not complete. He was not a fervent Zionist, and his political sympathies lay with Brit Shalom, the intellectual movement, comprised largely of German Jews, that abjured a Jewish state. Nevertheless, he gave crucial scholarly legitimacy to a fledgling organisation in Jerusalem, which would later provide a haven for many of the Jewish refugee scholars fleeing Nazi Germany.

Horovitz is best known for his study: The Earliest Biographies of the Prophet and Their Authors, published in 1927 It is the first comprehensive work on the early accounts of Muhammad’s life making full use of the available sources. It traces the emergence and growth of the Sīrah tradition from the generation of Muslims following the Prophet’s death down to the biographical dictionary of Ibn Sa’d in the 9 century, and thus covers many of the most important developments in the formative stage of Arab-Islamic tradition. Horovitz examined relations between Islam and Judaism in his Jewish Proper Names and Derivatives in the Qurʾān. Hruby (Father Kurt) ◊ (1921-1992) was born in Krems, Austria. His mother, of Jewish origin, converted to Catholicism in order to marry. Kurt was therefore baptised. At the time of the Anschluss in 1938, he escaped the Nazi persecution by leaving with his mother for Palestine. There he was a pioneer of Elijahv’s Qibbûs in the Jordan Valley, where he followed the rabbinical academic cursus or yeshiva. At the age of twenty, however, he decided to enter the seminary. In 1948, he returned to Europe, to Louvain, where he did his theology studies. He was ordained priest on March 18, 1956. Incardinated in the diocese of Liege, he taught at the Institut Catholique de Paris, which he joined in 1961. It was there that Brother Bruno met him. When he entered the Carmelite Seminary in 1956, Brother Bruno had already received from his master Father de Nantes the obedience of undertaking the scientific translation of the Qurʾān. He therefore assiduously attended Father Hruby’s course on rabbinical language and tradition, searching for the sources of the language of the Qurʾān. This is how he began to collect literary and philological contacts capable of explaining not only the ideas present in the Qurʾān, but also the origin of the Qurʾānic language, still absolutely unknown.

Hruby (Father Kurt) ◊ (1921-1992) was born in Krems, Austria. His mother, of Jewish origin, converted to Catholicism in order to marry. Kurt was therefore baptised. At the time of the Anschluss in 1938, he escaped the Nazi persecution by leaving with his mother for Palestine. There he was a pioneer of Elijahv’s Qibbûs in the Jordan Valley, where he followed the rabbinical academic cursus or yeshiva. At the age of twenty, however, he decided to enter the seminary. In 1948, he returned to Europe, to Louvain, where he did his theology studies. He was ordained priest on March 18, 1956. Incardinated in the diocese of Liege, he taught at the Institut Catholique de Paris, which he joined in 1961. It was there that Brother Bruno met him. When he entered the Carmelite Seminary in 1956, Brother Bruno had already received from his master Father de Nantes the obedience of undertaking the scientific translation of the Qurʾān. He therefore assiduously attended Father Hruby’s course on rabbinical language and tradition, searching for the sources of the language of the Qurʾān. This is how he began to collect literary and philological contacts capable of explaining not only the ideas present in the Qurʾān, but also the origin of the Qurʾānic language, still absolutely unknown.

From 1964, the development of the Catholic Counter-Reformation movement established by our founder, Father de Nantes, took priority and absorbed all our energy. However, Brother Bruno continued nevertheless to examine the text of the Qurʾān, collecting significant similarities of vocabulary between it and the rabbinical tradition. It was not until 1980 that Father de Nantes decided to proceed with the publication of the translation and systematic commentary of the Qurʾān. It is then that Brother Bruno resumed contact with Father. Hruby. He received him, was lavish with his encouragement, devoting whole days to answering Brother’s questions and providing him with every desirable learned reference. Brother Bruno submitted to him the proofs of the first volume of our translation of the Qurʾān before having it printed. Father Hruby wrote to him: “You know that in the interest of the cause, I would not hide from you any possible reservations, but there are none to make. Quite the contrary: what I have read so far seems to me to be solid, balanced, well presented and sufficiently irenical for no accusations based on assumptions to be made against you. You know, alas, the mentality of most people: they are less interested in the value of things than in where they come from… Still, one must not be too concerned about that; everyone is entitled to wear his “badge” proudly! Of course, I am not an Arabic scholar and therefore have no competence in that field. But it is also true that generations of professional Arabic scholars have failed to advance by so much as an inch in the fundamental question, which is that of the origins of the Qurʾān. And it is high time for this wall of silence to be breached. Not living in the “Land of Islam” and having no interest in gaining a “satisfecit” from the El-Azhar, you are sufficiently independent to be able to say things without pulling punches.” In 1992, Father Hruby wrote to Brother Bruno, “To hear that you are back working on the Qurʾān again is the best news of all. In this field you are doing a work that will last, the importance of which will, I am sure, be fully appreciated one day. The world of Islam is in a state of ferment, and the true nature of its foundation document, constantly referred to here, there and everywhere, is still cloaked in the darkest obscurity.”- J

Jamme (Albert) ◊ Belgian orientalist, specialist in Semitic languages, epigraphist (1916-2004). Priest in the Community of the White Fathers (Missionaries of Africa). After secondary school, at the Saint Joseph College in Chimay, he entered the White Fathers (Missionaries of Africa) in Glimes (1934) to study philosophy. Then, he made his novitiate in Algeria, at Maison Carrée (1936). He took his oath in Heverlee (1940) and was ordained priest (1941). After his studies in Louvain, he went to deepen his knowledge for two years at the École Biblique de Jérusalem, then at the Institut des Belles Lettres Arabes (IBLA) in Tunis (1948). After further studies in Louvain (Doctorate of Theology and graduate in Orientalist Studies), he left for Rome (1952). After graduating in Sacred Scripture, Religious Sciences and Education, he was appointed Research Professor at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. (1953-1999).

Jamme (Albert) ◊ Belgian orientalist, specialist in Semitic languages, epigraphist (1916-2004). Priest in the Community of the White Fathers (Missionaries of Africa). After secondary school, at the Saint Joseph College in Chimay, he entered the White Fathers (Missionaries of Africa) in Glimes (1934) to study philosophy. Then, he made his novitiate in Algeria, at Maison Carrée (1936). He took his oath in Heverlee (1940) and was ordained priest (1941). After his studies in Louvain, he went to deepen his knowledge for two years at the École Biblique de Jérusalem, then at the Institut des Belles Lettres Arabes (IBLA) in Tunis (1948). After further studies in Louvain (Doctorate of Theology and graduate in Orientalist Studies), he left for Rome (1952). After graduating in Sacred Scripture, Religious Sciences and Education, he was appointed Research Professor at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. (1953-1999). Jarden (Dov) ◊ Byelorussian-born Jewish mathematician and linguist (1911-1986). Specialist in Medieval Hebraic literature, he was professor at the University of Haifa, Israel. He was co-author of Ozar rashe tevot, a thesaurus of Hebrew abbreviations.

Jarden (Dov) ◊ Byelorussian-born Jewish mathematician and linguist (1911-1986). Specialist in Medieval Hebraic literature, he was professor at the University of Haifa, Israel. He was co-author of Ozar rashe tevot, a thesaurus of Hebrew abbreviations. Jastrow (Otto ) ◊ German Professor Ordinarius for Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures (1942-....). He taught at two German universities (Heidelberg and Erlangen-Nürnberg) before taking office at Tallinn University in 2008. Over the decades he has conducted linguistic field work in a number of Middle Eastern countries, i.e., Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Israel. He speaks Arabic (several dialects), Turkish, Hebrew and Aramaic. He is author of 12 books and up to 100 articles. His main subjects of research are Neo-Aramaic languages and Arabic Dialectology. He holds a Ph.D. in Semitics and Islamology from the Saarbrücken University, and a Habilitation from the Erlangen University.

Jastrow (Otto ) ◊ German Professor Ordinarius for Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures (1942-....). He taught at two German universities (Heidelberg and Erlangen-Nürnberg) before taking office at Tallinn University in 2008. Over the decades he has conducted linguistic field work in a number of Middle Eastern countries, i.e., Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Israel. He speaks Arabic (several dialects), Turkish, Hebrew and Aramaic. He is author of 12 books and up to 100 articles. His main subjects of research are Neo-Aramaic languages and Arabic Dialectology. He holds a Ph.D. in Semitics and Islamology from the Saarbrücken University, and a Habilitation from the Erlangen University. Jeffery (Arthur) ◊ Australian Methodist minister and renowned scholar of Middle Eastern languages and manuscripts (1892-1959). He taught at the School of Oriental Studies in Cairo (1921-1938), then from 1938 until his death jointly at Columbia University and Union Theological Seminary in New York City. He is the author of extensive historical studies of Middle Eastern manuscripts. His important works include Materials for the history of the text of the Qur’an: the old codices and The Foreign Vocabulary of the Qur’ān (1938), which traces the origins of 318 foreign (non-Arabic) words found in the Qur’ān.