Georges de Nantes.

The Mystical Doctor of the Catholic Faith.

11. THE FIRST DISCIPLES

WOULD Fr. de Nantes, who had been expelled from the Diocese of Paris, find himself appointed to the chair of theology at the Major Seminary of Grenoble ? This is what his bishop desired but a cabal was mounted against him on account of his involvement in Action française. He was once again out on the street, not knowing which way to turn, poor Father ! The psalms of distress in his breviary took on a singular emphasis in this summer of 1952, and were his only solace, as he confided later on. 1

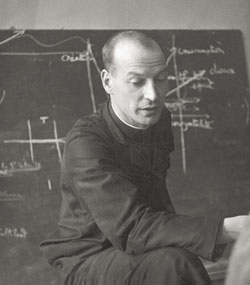

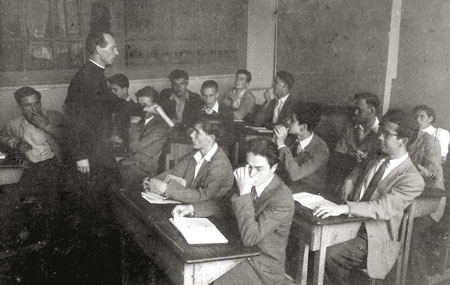

In 1953, at Saint Martin’s College in Pontoise, the class of religious instruction was held in the philosophy and mathematics classroom.

His teaching : The cycle of the Father, the cycle of the Son, the cycle of the Holy Spirit introduced us into the only religion that established between Heaven and earth the bonds of a divine circumincessant charity, even in politics, which is a royal work.

It was then that a devoted confrere recommended him to the Reverend Fr. Duprey, superior general of the Oratory. The latter sent him to Fr. Tourde, the superior of Saint Martin’s College at Pontoise, where he was “ exiled ”, like a parliamentarian under Louis XIV, in disgrace (not royal but republican disgrace !). There he was assigned the religious instruction course – a class that was traditionally heckled by the pupils – to teach to both the boys of the third form and the seniors. One might as well say that he was given the last place.

AT SAINT MARTIN’S COLLEGE.

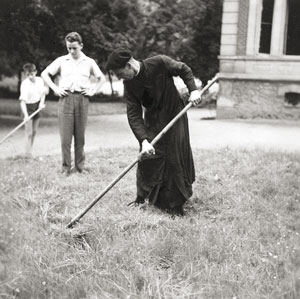

This institution had been founded in 1929, by the same Fr. Duprey, in the open and spacious setting of a magnificent and immense park containing several properties in which the different classes were divided into “ Houses ” : the Priory for the boys of the fifth and sixth forms, which I [Bruno Bonnet-Eymard] entered in October 1947 ; the Abbey for the fourth and third forms. Its tower is all that remains of an 11th century monastery, Saint Martin’s Abbey. The “ seniors ”, beginning with the second form, were divided among the Chateau, the Pommeraie and the Hermitage.

The classes of the sixth and fifth forms were used as testing grounds for “ activity methods ” : team work involving interrogating the station masters of Pontoise, Saint-Ouen and Conflans, and archaeological research in the quarries of Cergy. It was a perpetual outing, a dream life. We acted Antigone, Sophocles’ tragedy, that first year for the school festival, which had been fixed for Ascension Day, on the square in front of the Priory. The following year, in 1949, we acted the Persians by Aeschylus, on the terrace of the Chateau.

At this rate, the examination results threatened disaster. In the fourth form, the method had to be changed and some work had to be done. It was then that I made a new friend, in the person of a serious boy from the North, from Valenciennes, a “ senior ” in the third form, who used to help me with my Greek translations. Gérard, his little brother, more or less the same age as myself, soon came to join him, and we became inseparable. That certainly would not have lasted, especially as we were separated in the second form, Gérard to the Pommeraie and I to the Hermitage. At that age, friendships are made and unmade.

FINALLY DE NANTES CAME.

Of Fr. de Nantes’ first year at the College (1952-1953) I have one very significant memory, which dominates all the others : he was walking down the avenue leading to the Hermitage refectory, wearing a Basque beret as big as a “ pie ”, reciting his breviary. He raised his eyes, gave me a broad smile, and then continued with his prayers.

On the top floor of the Chateau, the tenant of the room next door to his, Fr. Marcel Rigal, became his confessor and friend. He had the face of a peasant from the Auvergne, with an attractive dignity and a rather sad kindness ; he was a man of rare erudition, enamoured of the original Oratory, that of Bérulle and of Madame Acarie, the Cardinal’s cousin, who introduced the Carmel in France (1604). He liked to tell her story with his rough, engaging country accent : “ There was once a great Lady who walked above the earth : with her ecstasies she touched Heaven, and with her goodness she touched the earth. Though very great, she thought herself small, which added to her greatness. She is now called Blessed Marie of the Incarnation. Christian people now pray at her tomb at the Carmel of Pontoise ”, the oldest Carmel in France.

Fr. Rigal took his friend Fr. de Nantes to the Carmel, where he spoke to the nuns about their Father, St John of the Cross. The superior asked him to come back, because “ none of our Fathers speak in this way about St. John of the Cross ”.

One day in September 1953, Fr. Tourde needed a “ House Master ” for the Pommeraie and a philosophy teacher for the final year. Only a few days before the beginning of the new term, this vacancy was a disaster. Rigal declared that de Nantes was capable of taking on both posts at a moment’s notice. Fr. Tourde knitted his bushy eyebrows : had not this priest been with Action Française ? Was he not still ? Necessity, however, knows no law, and even more, the unfathomable designs of our Heavenly Father, our mercy.

You should hear Brother Gérard tell how things completely changed that year at the Pommeraie, “ after a minimum of resistance by the seniors, for the sake of honour. ” Fr. de Nantes, combining his two functions as chaplain and House Master, would gather all his little people in his office, which was also his bedroom, for prayers every evening. First of all, he would draw the lesson of the day that had passed and would announce the programme for the following day. The first time he so gathered them, Cousin wanted to sit down and fell down onto the bed. It was a brutal shock : beneath the simple coverlet there was nothing but a plank.

In his morning prayer, when everyone was still sleeping, “ the fatherly priest liked to compare himself to the wine grower that the length and the weight of the day would see pruning his vineyard with care, ” Brother Gérard attests. Once a week, Father celebrated the “ House Mass ”, absorbed in an impressive recollection that made an impact on every one of those ruffians of the Pommeraie. After the Gospel, he would give a homily, always unexpected and full of feeling, tender devotion and understanding of the Scriptures. One day, he asked Gérard Cousin to accompany him to the Servite Sisters (Servants of Mary) to serve his Mass. The nuns devoted themselves to a clinic next to the College of which Father was the chaplain. The altar boy was in seventh heaven, breathing in the good clean smell of fresh linen, wax and incense ; he entered into the recollection of a nuns’ chapel, full of warmth, light, candles and flowers. He thought he had been entrusted with some State secret when, after their visit, Father told him that the superior was “ a remarkable woman. ”

In the meanwhile, we boys of the Hermitage House were under the more lax authority of a family man as House Master, who spent his time with his wife and children in their apartment and left us to our own devices. My good fortune, however, was to enter the final stage of philosophy that year. I could mime the first class as though it were only yesterday.

A PROCLIVITY FOR THE TRUTH.

He began with a prayer : Father knelt on the edge of the dais and was suddenly plunged into a deep recollection. We had never seen that before. Then, on the blackboard I saw a table summing up the whole universal history of human thought To the right was the line of the “ fixists ”, with the name of Parmenides heading the list : being is one, immutable, absolute. To the left, Heraclitus : everything moves, nothing stays. Every philosopher throughout history is attached to one or other of these basic intuitions. As for us, budding philosophers, where were we going to place ourselves, asked our young, twenty-nine year old philosophy teacher, to the right or to the left ? It took us a whole year to find our place : in medio, not as a centre party in Parliament, but as children of the Church, under the aegis of her Doctors, “ in the middle. ”

Thus straightaway, all human wisdom took shape as divine wisdom in our minds : we were “ Aristotelico-Thomists. ” This new conviction that we intelligently and proudly put forward earned us complete success in the Baccalauréat exam. A hundred per cent success rate : all thirty three candidates passed the exam, which had never been seen before. Fr. Tourde owed Fr. Rigal a great debt for having recommended Fr. de Nantes.

And we too, of course ! We had contracted for life a proclivity for the “ truth ” : it is enough to write this simple, luminous word in order to feel, in writing it, and to express the rich, confused, flavoursome and diffuse impression that is the intuition of the existence of beings. We were invited to exercise and to savour this untiringly. I rediscovered it in all its original freshness the day that we went to Saint Martin College on pilgrimage with the Permanence de Paris 2, amid the avenues of that park, which are lined with magnificent trees, the privileged mediators of that intuition. It is an intuition that is accessible to anyone who wants it, at least to any mind uncontaminated by Cartesian solipsism or Kantian criticism. It was our good fortune to be immunised from the beginning of our thinking lives against this infirmity, and the impiety that flows therefrom under the name of “ agnosticism ”, irremediable when contracted at that age.

There was also another advantage ; our adolescent “ problems ” had vanished, dispersed like fog in the full sun of the being of things with which we were enraptured. Resolutely opposed to Descartes and to Kant, it made existentialists of us, not after the manner of Jean-Paul Sartre but as disciples of St. Thomas, since the experience of the stability of essences and of the laws governing their mutual relations clearly show that the world is not “ absurd ”.

Speaking of the existentialists, Father said : “ My friend, Gabriel Marcel ”, and we learned that he used to go and see him every week when he went to Paris on his “ Vespa ”. Our Christian existentialism wedded happily with Aristotle’s intellectualist realism, and completed it. In the presence of the same trees in the park, we learned to forget their “ accidental ” magnificence in order to single out the “ essence ” of tree. This is difficult.

Reading Maritain at the seminary, a few years later, I understood our good fortune. This author, who was presented as THE great restorer of Thomism, declared that “ abstraction ” is the exercise of the commonality of mankind, but that “ the intuition of being ” is exceedingly rare, accessible only to a small number of very great minds : Maritain himself and a few others ! It was a ridiculous claim, which was the ruin of contemporary neo-Thomism. We were, without knowing it, in the school of a very great philosopher who, with incredible ease, associated our youthful minds with the major intuitions of his genius, because to do so was primarily a communion in the very being of things.

TRUTH IS RELATIONAL.

We acted the Greeks again that year ; or rather, our pedagogue acted for us and in front of us the Socratic Dialogues, miming, explaining and questioning Euthyphro, Crito, Gorgias in the person of his pupils, who played their roles very well : they listened open-mouthed.

I remember a friend whom we called Pachy, who had revolted against his father. Finding himself in the same situation as Euthyphro, distraught and shaken, he returned to his father and asked his forgiveness. He was eternally grateful to his philosophy prof who had enabled this reconciliation to take place. His filial fervour became proverbial among us and gave rise to an unusual incident during our end of studies retreat, organised by the Oratorians in Belgium’s royal abbey of Orval. Fr. de Nantes accompanied us, but the retreat was preached by Fr. Liégé, a Dominican imbued with a revolutionary spirit who would raise havoc in the Latin Quarter a few years later, in May ’68. Fr. Liégé had arranged a “ forum ” on “ love ”! The anticipated “ exchange ” was a drag, for we hardly had any experiences to “ share. ” Suddenly Pachy raised his hand : “ I have a fantastic experience of love ! ” All eyes were fixed on him ; those of Fr. Liégé sparkled with curiosity : “ the love of my father ! ” The Dominican, disappointed, ended up calling us philistines, and daddy’s boys, and refused to take part in the convivial meal which was to conclude our college life.

Without the slightest concession to the prevailing errors of the post-war and post-liberation period, Fr. de Nantes was already teaching us a “ total ” truth with infectious enthusiasm. Theology was its foundation that was laid in the religious instruction course, which we no longer thought to heckle as was the tradition in that liberal college. “ The cycle of the Father, the cycle of the Son, the cycle of the Holy Spirit ” introduced us into the only religion that established between Heaven and earth the bonds of a divine and human circumincessant charity : the Son of God becoming Son in this world, the Son of Mary in the village of Nazareth, teaches us to love every kind of filiation on earth.

The philosophy courses carried on from theology : returning to the sources of being, Fr. de Nantes reorganised all human knowledge into a double view of nature and relations, defining the privileged being that is the human person – we knew that this was the object of his research that drew him to Paris every Tuesday – by his relations of origin. Filiation then finds its place as a definition, and all the philosophy that follows from that is “ turned outward, ” becomes extroversive. The child is turned towards his parents as the only begotten Son of God, the Word, is turned towards His Father, the disciple towards his master, the spouse towards her husband, the head of State towards the common good, the colony towards the mother country, the head of the Church towards Christ, in a constituent “ ascending dependence ” that builds a mystical body in which the bonds of nature join with the bonds of grace in which every personal life, like that of the social body, is ordered to charity. This view was plenary, satisfying, and balanced. Our young minds, however, were unable to weigh up its divine height, its human depth, its orthodromic length and its Catholic breadth.

Nevertheless, there followed from this a morality situated at the opposite pole from the rights of man, which taught us to consider as null and void the so-called “ dignity of the free, autonomous and independent human person ” (dignité de la personne humaine, libre, autonome et indépendante [abbreviated p.h.l.a.i. in our class notes]) and which immunised us against all forms of racism, socialism and the democratic pride that was illustrated by the current events that Father explained to us. He did speak to us about politics, and this is perhaps what gripped us the most. French Indochina was in its dying moments. We also learned to venerate “ Marshal Pétain, ” the father of the Homeland, acquiring for life a visceral hatred for all protest movements, anarchy, “ Resistance fighting, ” and revolution.

In my small head, I ended up imagining Socrates in the guise of him who played the role as a consummate actor : the Greek philosopher must have been a kind of saint resembling Jesus Christ. Thus Father de Nantes read and explained Crito, or the Apology, as though he were defending himself in his own trial. The day came when the fiction became reality. Little by little, the entire teaching staff, with the exception of Fr. Rigal and a few others, leagued against this “ seducer, ” this “ corruptor of the young. ” There was good reason !

In fact, for twenty years the history professor, nicknamed the nabob, had taught that Dreyfus was innocent. Now one day, at table, we spoke about this to our Socrates who took an interest in all that we did. He had an answer for everything ; he knew everything. At the next class, the nabob thought the sky had fallen in : a hand was raise in front of him during the class, respectfully but insistently asking permission to pose a question. The nabob, however, had nothing to respond, no proof to offer for Esterhazy’s alleged culpability. At the end of year dinner at the Pommeraie, the absence of the nabob was noticed.

EXCLUDED AGAIN.

Father held out another year (1954-1955,) with the same happiness, the same alacrity and the same success. Only Brother Gérard would be able to relate the sensational recovery of the Pommeraie, that passed from last to first place, at the head of all the “ Houses ” of the college, carrying off all the cups of the sports competitions : football, athletics, etc., and also winning all the laurels in the examinations.

“ Thus it was that he founded ‘ Marian teams, ’ with a project for a pilgrimage to Fatima : ‘ All you have to do is to take the La Bédoyère family’s Dodge and go ! ’ In the end it was not Fatima but a pilgrimage to Lourdes, followed by a camp in the Pyrenees dedicated to the study of the Epistles of St. Paul. ” 3 It was unforgettable !

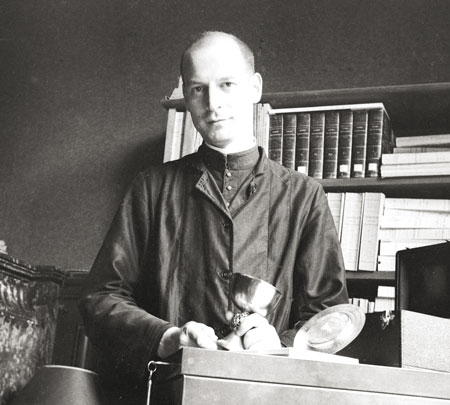

In June 1955, at the end-of-year dinner, Fr. Tourde showered Fr. de Nantes with the highest praise. The thoughts of the latter, however, were elsewhere. For it was not the College that had made a breach in his heart during his three-year stay in Pointoise, but the Carmel, and he had requested entry into the noviciate of Bernay-en-Champagne, in the Sarthe, after having made a retreat the previous February. Secretly, Cousin was thinking about following him, after having organised the most wonderful of celebrations at the Pommeraie, during which the students offered their Father and master his beautiful chalice, an imitation of Pope Gelasius’ chalice in the Louvre Museum.

“ You yourselves, ” Father de Nantes told them, “ composed the superior harmonies according to which you will henceforth appear to me, grouped together, unanimous, in an extraordinary silence around my chalice, which is also yours : like young verdant olive tree plants, so are the sons of the Church around the table of the Lord. ” 4

At the same time that he was showering praise on Fr. de Nantes, the very same Fr. Tourde was writing to the Carmel’s master of novices to caution him against his postulant, warning him that this priest only exhorted the students to religious observance the better to submit them to his political Action française ideas : like Socrates, he truly violated souls, and turned vocations away from the Oratory !

Thanks to Fr. Tourde, Fr. de Nantes did not enter the Carmel ! Hurrah for Fr. Tourde ! For where would we be if the doors of the Carmel had closed on our Father that year ?

FOR US, “ THE INCOMPARABLE FRIEND ” WAS FR. DE NANTES !

“ During the following summer, ” Brother Gérard relates, “ on vacation with Fr. Vimal, he [Fr. de Nantes] entrusted me the task of going to fetch Fr. Vimal’s ‘ Vespa ’ in a building near the Luxembourg Gardens, with the mission of conveying it to Tournus and Bracion, where they were, a distance of 400 km. I enthusiastically replied, ‘ yes, ’ and I was not disappointed, for I met uncle Louis 5 for the first time. I listened to him and I began to understand where our Father's wisdom, fortitude and stirring enthusiasm came from. ” 6

For my part, with some audacity for which the benevolent reader will forgive me, I would like to appropriate what our Father wrote about Fr. Louis Vimal. We have already quoted a few passages, but I am unable to express better what our Philosophy professor was in 1953 at Saint Martin College in Pointoise where, the child that I was, saw “ Someone to whom he was going to attach himself mysteriously, like the ivy to the tree, like the young Tobit to the Archangel Raphael, in short, as disciple to incomparable master. ” 7

For me, Fr. de Nantes was this “ incomparable master ” :

“ Must I say it, cruel though it is ? He was not like the other professors, whose knowledge appeared to be frozen, reduced to a definitive system, a formal digest to be swallowed like so many dry pills [the nabob’s history classes !]. With Fr. de Nantes, I discovered a mingling of light and shade in which I came up against dense, suspicious darkness [the Dreyfus affair, de Gaulle, the ECSC 8, etc.]. In all the subjects that he taught and in those taught by others on which he cast certain devastating, liberating looks, he brought things to life and made them intensely interesting. In all, he made me see the conflicts of the ignorant, the plots of false teachers, and the often stupid and wicked persecutions by the majority of those who labour in the cause of truth. Thus, in following him, I had to cut a path for myself towards sound doctrine, passing through swamps and thickets or intractable briars. He, however, had already gone over this difficult ground before me, for I saw him as so much older than I in view of his knowledge, and he would warn me of the sign posts to look out for, like so many white pebbles, to keep me from losing my way.

“ Ironically and ruthlessly, he would harass me over every blunder I made, – I who was always speaking too fast, thinking I knew, and proffering enormous stupidies – whilst he, never emphatic, seemed to me to know the solution to every difficulty, the solution that could be found nowhere else and that was never said, and without which our masters themselves went astray [...]. Even though at each of my visits he always gave the impression of being annoyed and anxious to put an end to it, I noticed, however, that he seemed very pleased to receive me. This was not because of me, or should I say because of my nullity, but because as soon as I entered his room I parried his irritation by providing him with matter to teach me, to open my eyes, to make me less ignorant. ” 9

It was the same for me. Fr. de Nantes himself related our first exchange that turned to my embarrassment :

“ You came back after a few days of absence. I can still see us in front of the splendid gate of the College. ‘ Well, Bonnet-Eymard, have you studied your philosophy lesson ? ’ Impertinent, you replied : ‘ Yes, but I wouldn't say that I understood it! Either it does not make sense or I am completely stupid ! ’ Of the two solutions, I chose the only one that was compatible with my honour, although I explained to you that this chapter on perception was one of the most difficult in our psychology programme. We have continued this dialogue – which soon became a trialogue, so to speak – for twenty-six years, always friendly, slightly ironical, paternal and filial, that led to the triple body of our hierarchically organised certitudes : Catholic, royalist, communitarian ; for God and the Fatherland. The C. C. R. was born, unknowingly, in 1954. It was the year of Dien-Bien-Phu, the year of the banishment of a certain Bishop Montini from the Vatican to Milan, and soon the Bloody All Saints’ Day that was to begin the tragedy of our French Algeria. About all that, we were already speaking. ” 10

“ This tradition, this discrete delivery of ancient treasures ” to new minds, was at Pontoise, as already in the seminary of Issy-les-Moulineaux in 1944-1945, “ a setback for the revolution ! ”

SPIRITUAL FILIATION.

There was, however, even more. From him to his disciples, the bond of paternity - filiation established ten years earlier by Fr. Vimal recurred.

“ The important thing was not to imagine myself, one fine day, capable of discerning the true and the good all by myself. How could I ever have such an idea, when I constantly received from another, from him, all that made my treasure ? In my dear papa I had had a master of thought, but I had left him before reaching or even perceiving the boundaries of his knowledge. This peerless friend, taking over from my father, never ceased to answer all my questions or to anticipate them with his warnings. He would burden me with books – always the best ! – and their underlings in red and blue pencil – drawn by ruler with that neatness that he put into everything – were another help, added to the advice he had given before. From year to year, I never encountered the limitations of his knowledge, whilst he made me very much aware of mine, to tease me a little, to deepen the awareness of my ignorance and to stir my curiosity. ”

Guided by this ‘ secret Counsel ’ and “ thanks to so many practical exercises, I had acquired a certain mastery of the system of thought that was to be my vocation in the service of the Church. It was a rigorous method, intolerant of the least approximation applied to the highest, the most living, the only adorable, immense and vertiginous positive data: the divine action at work in human history, the revelation of God’s Mystery in all its fidelities and mercies. ” 11

As I have said, Fr. de Nantes’ relational philosophy, which is a return to individual beings through the consideration of their ‘ vocation, ’ as determined by their mutual relations, is full of practical and personal consequences. That is how he became a father for me, as for Brother Gérard. Our “ problem ” in our last year was : what will I do next year ? One day, I decided to go talk to him.

“ I will evoke, ” he himself related, “ this conversation that we had in the alley of the orangery, from which the clash of fencing practice reached our ears, on that famous day, my Brother Bruno, when you confided to me your ambition of becoming a diplomat. ‘ Well ! a fine job that is ! ’ I exclaimed. Then I drew for you the incredibly sinister picture of the day of an embassy attaché in Djakarta or Peking and, in comparison, I related my fine day : morning Mass for the community of the Servite Sisters (Servants of Mary), of which I was the chaplain, the philosophy classes with such interesting students, visiting the sick in Doctor Breton’s clinic, a short horseback ride at the Cergy parade ground, my theological work and, finally, this spiritual direction of a great gawk who was letting himself be taken in by the mirages of a decadent world. Could it be said that I took advantage of your youth ? I would not have won you over, however, if the interior Master had not already made a breach and penetrated deep into your heart. ” 12

THE PRIEST, THIS OTHER CHRIST.

Yes, the interior Master had made a breach through the intermediary of his faithful servant and perfect friend. If the grace of our Father meeting Fr. Vimal was that of “ the extreme beauty, truth and fruitfulness of a priestly friendship, ” for me, for us, our grace was to have a share, like disciples and sons, in the ministry of this priest, this other Christ, and therefore in his vocation and his service of the Church.

“ Now I am going to say something crazy, an implausible thought, which I could however express in a well-known – in fact too well-known – formula that is so perfectly accepted as to have become meaningless: Sacerdos, alter Christus, the priest is another Christ ! [...]God is truly inaccessible, Christ has made Himself invisible, and the Blessed Virgin allows hardly anyone to touch Her knees 13, not me at any rate. So, what sensation, what sentiment, what emotion can ever give me the certainty that I love God, and that I am truly and really loved by Him alone as none other could love me ? It is a surprising intimate experience. In this desert, in this solitude, thousands and thousands of purely human images press against the windows of my memory, of a priest saying Mass, receiving me, talking, laughing, joking or getting angry, taking me on a hundred walks and visits to churches, in a thousand conversations, and all that is – how shall I put it ? – the bearer of an undeniable certitude that nothing would have come of it, would have marked my mind or would have remained as a treasure of grace if Jesus Christ had not been, was not always and would not be for all eternity its living principle, its unalterable essential, its absolutely divine object : it is He after all, the Truth of all being, the movement, the life, the goodness, the wisdom, the joy, the alacrity of my incomparable friend, even though he always wanted to hide it from me, misleading me by a proper and necessary modesty. This Truth is Jesus Christ ‘ spread and communicated ’ as Bossuet says of the Church ; and it is He Who loved me, fed me, carried me, wrought by the thousands of graces in this friend, in this priest. How I loved Him in him, – ah, I would not dare to write it about another – with a certain and ever conquering love.

“ Now such an admission is truly ridiculous, because it is true. ” 14

(1) CCR no 79, October 1976, p. 1.

(2) Account of this beautiful day in CCR no 267, May 1994, pp. 19-22.

(3) Brother Gérard’s testimony : A filial look, CRC n° 274, June 1991, pp. 23-26.

(4) The end of the year speech, June 16, 1955.

(5) Fr. Vimal was not our Father’s uncle. Uncle Louis was only a nickname .

(6) Brother Gérard’s testimony, CRC n° 274, June 1991, p. 24.

(7) Memoirs and Anecdotes, Vol. II, p. 364, published in CCR n° 251, October 1992.

(8) European Coal and Steel Community.

(9) Ibid.,pp. 367-368, published in CCR n° 251, October 1992.

(10) Homily for the feast of the Transfiguration, August 6, 1980 on the occasion of the perpetual vows of our Brothers Bruno of Jesus and Gérard of the Virgin. CRC n° 157, September 1980, pp. 13-15.

(11) Memoirs and Anecdotes, Vol. II, p. 372-374, published in CCR n° 251, October 1992.

(12) CRC n° 157, p. 13.

(13) This is an allusion to an apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary to St. Catherine Labouré that took place on the night of July 18 to 19, 1830 : “ Sister Catherine heard herself being called : ‘ Sister Catherine ! Sister Catherine ! ’ It was her Guardian Angel who had awakened her in order to escort her to the chapel. He was of the purest light. The doors opened before them, as one reads in the Acts of the Apostles. After a moment of waiting on her knees in the chapel choir, the Sister heard ‘ the rustle of a silk dress coming from the sanctuary. ’ “ ‘ Behold the Blessed Virgin, ’ said the Angel in a loud voice. In just one bound Sister Catherine found herself on the steps of the altar, her hands folded on the knees of the Blessed Virgin, who was seated in the Director’s chair. It was, the Sister would say, ‘ the sweetest moment of my life. ’ ” (CCR 333, Sept. 2000, p. 26)

(14) Memoirs and Anecdotes, Vol. II, pp. 383-384, published in CCR n° 251, October 1992.