He is risen !

N° 229 – February 2022

Director : Frère Bruno Bonnet-Eymard

Letter to Bishop Alexander Joly

Part one

IT is with supernatural joy that the Little Brothers and Little Sisters of the Sacred Heart welcomed your appointment by the Holy Father to the See of the Church of Troyes, which had been vacant for almost a year. We know that you yourself receive this mission with great joy despite the grave worries that necessarily accompany the task of teaching, sanctifying and governing the little flock committed to your care... in order to guide and lead it, with the help of your priests, to “Heaven, the only goal of all our works” as little Thérèse put it so well, with this radicalism very peculiar to saints. For the brief moment that our lives represent on this earth is tragic. At its end, it is either Heaven for unending bliss, or Hell, for an eternity. It is a truth of our Faith revealed by Our Lord and recalled by Our Lady – have we forgotten it? – She did not hesitate to show this appalling Hell to three little children, Lucy, Francisco and Jacinta, on July 13, 1917 in Fatima, while recommending to each of them and with anguish the daily recitation of the Rosary and revealing the devotion to Her Immaculate Heart, the refuge of souls and the way that leads them to God.

So be assured, Excellency, of our prayers and sacrifices for you.

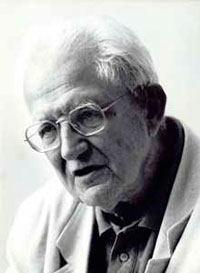

I, however, cannot help but associate your name with the Doctrinal Commission of the Bishops of France. It issued a severe Warning to inform, to alert all your confreres about the doctrines of Father Georges de Nantes, founder of our communities and of the Catholic Counter-Reformation movement, whose successor I am. Our Father gave up his soul to his “most cherished Father of Heaven” on February 15, 2010, fortified by the sacraments of the Church given several times by priests in communion with their bishop. He was buried in Christian cemetery after a funeral mass celebrated in our chapel of the Maison Saint-Joseph, by Father Raymond Zambelli, rector emeritus of the sanctuaries of Lisieux and Lourdes, with the full knowledge of Bishop Marc Stenger. He died as a worthy son of the Church, and I might add, without being under any legitimate canonical sanctions.

With the death of our beloved Father, one might have thought that the ‘de Nantes’ affair would finally been settled: the very small group of his disciples and friends of the three religious orders would separate and disperse definitively amongst the People of God... Twelve years later, however, – and God knows that they are not great in number – it became clear that this is not the case! So something had to be done! But what? A warning!

When this document was published on June 25, 2020, it did not seem appropriate to me to prepare a complete and systematic response, for several reasons.

Mainly due to the fact that although the Doctrinal Commission, a body by definition collegial, can issue opinions, if it deems it really useful for the good of the Church of France and souls, this commission as such, whatever the qualities and rank of its members, has no authority to render doctrinal judgements that can replace the personal exercise of the teaching power held by the bishops for the sole territory placed under their jurisdiction. Thus replying to a Doctrinal Commission concerning a document whose author or authors are not clearly identified would have been on my part to begin to give recognition to an authority that it does not have.

Moreover, the Warning ends as follows: “Each bishop in his diocese may make whatever use he deems appropriate of this Warning to enlighten the faithful who may be troubled by the errors of the Catholic Counter-Reformation.”

Yet at the very moment when the members of the Doctrinal Commission solemnly recognised the authority of each ordinary in his diocese to form his own judgement and to determine what action to take concerning this Warning, their authority was immediately ‘circumvented’ by the publication of this Warning on the Conference of Bishops of France’s website. Indeed, Laurent Camiade, Bishop of Cahors, considered himself authorised to give a spontaneous commentary in an interview granted to the newspaper La Croix, which did not fail to reproduce extensive extracts from the document.

So without waiting for the judgement of the Ordinaries, anyone who is or is not a member of the Church is free to read this document and form his own opinion. What then is the role of the bishops if some of them, through the media and public rumours, put pressure on the others, instead of allowing them to exercise their personal magisterium, the only legitimate one, which they claim to be defending against us? What I report here perfectly illustrates what our Father wrote about episcopal conferences and commissions: “These parasitic organisations claim a consultative power that allows them to dominate popular opinion, and a deliberative power – always usurped – that lets them wield the bishop’s authority.”

Our Father added: “These anonymous, irresponsible oligarchies prove to be fundamentally revolutionary; every heresy and schism finds shelter and support amongst them.” The Warning seems to prove our Father wrong since apparently it is the defence of the Faith, of the “dogma of the Faith” to use this expression that Our Lady used in the second part of Her great Secret revealed at Fatima on July 13, 1917, which motivates this Warning against the alleged errors of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, in particular against a “sensualist conception of the Eucharist” and which might “possibly” disturb the faithful.

I have the right to question the truth and sincerity of these apparent intentions.

What actually troubled the faithful, what outraged them, at the very moment when the members of the Commission were finalising this Warning, was the general – almost absolute – ban, enacted by the French government during the two periods of confinement to attend the Mass celebrated by their pastors in the churches of France. This ban was rightly felt to be a very insidious and extremely effective act of persecution. It directly targeted not so much the priests and bishops, but the sheep who were forcibly separated from them, since the Republic claimed for itself their authority to watch over their physical welfare, but in contempt of their spiritual welfare. Yet during these weeks, these months even, of forced confinement, there took place a distressing revelation of hearts among the pastors, between those totally consumed by apostolic zeal and who found thousands of solutions to exercise their ministry one way or the other, especially by distributing Communion, and those who abandoned their flock.

In this regard, the example of Norbert Turini, Bishop of Perpignan, deserves to be cited. He enjoined his priests “not to set themselves up as accountants of their Sunday assemblies and therefore not to reject if this were the case, the 31st person and the following who would present themselves.” Aware, however, that this would expose them to sanctions, Bishop Turini added: “I take full responsibility for it and if necessary I will be personally accountable before the public authorities.” This does not exclude, moreover, respecting prudent health regulation so as not to spread an epidemic which must, however, be explained as a punishment, a mercy, an urgent call of the Good God to conversion.

It is true that in such a context and on such a subject, making the right decisions presupposes having the Catholic Faith, faith in the Real Presence of Our Lord in the Blessed Sacrament, in His “Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity (…) present in all the tabernacles of the world.” The faithful and their priests then witnessed this other revelation of hearts by noting this division within the Hierarchy described with alarm by Jean-Marie Guénois in the columns of Le Figaro of November 23, 2020:

“One bishop (...) said he was painfully astonished to see ‘a theologically divergent Eucharistic Catholic faith’ even among the bishops. This fact reflects a taboo debate in the Catholic Church: some theologians, priests, bishops and some cardinals, have espoused the theses of Protestantism which consider the Eucharistic ‘presence’ of Christ as ‘symbolic’ and not ‘real.’ So not absolutely ‘sacred’ to the point of fighting for it. The big surprise in this area came from Rome this week, from a future cardinal (...) chosen by Pope Francis to head the important synod of bishops. In the world-leading Jesuit magazine, La Civilta Cattolica, of mid-November, this prelate called those who complained of not being able to attend Mass ‘spiritual illiterates.’ He asked the Church to take advantage of this crisis to break with pastoral care aimed at ‘leading to the sacrament’ in order to pass ‘through the sacraments to the Christian life.’ ” Jean-Marie Guénois continued: “a cardinal very close to the Pope, relativizing the importance of the Mass! These words shocked many, but not all, bishops. Part of the Catholic Church doubts the Eucharistic faith, which is one of her foundations.”

Some bishops, however, and there is no doubt about it, have kept intact a living faith in the Real Presence such as Bishop Bernard Ginoux at the head of the diocese of Montauban as evidenced by the article he signed in the December 3 to 9, 2020 issue of Valeurs Actuelles. In it, he states, on the one hand, that “our faith is carnal” – this is precisely what the Warning you signed denies, yet it is precisely what we are reproached with! – and, on the other hand, that it is necessary for the faithful to attend Mass: “Does the life of the faithful Christian need the Eucharist? We can answer yes without a doubt. Of course, we have many ways of living our faith, but the Mass is unique because it is there that physically, really, we live this exchange. There is a real and efficient encounter (if our heart is pure) between the Saviour and us: the Eucharist communicates the fruit of Salvation. The faithful receive it through faith and the divine presence.”

Is it necessary to say more to explain why I doubt that the trouble of the faithful, especially in their Catholic faith in the Eucharist, can constitute the true and sincere reason for the Doctrinal Commission’s Warning? My doubts are all the more justified because in the current distressing context of a generalised and vertiginous drop in both the faithful’s religious practice and their most elementary knowledge of the truths of the Catholic Faith, it would be very surprising if the few theological proposals of Father Nantes on the Eucharist, the Sacraments of Matrimony and Holy Orders, on the Blessed Virgin Mary and even on the Holy Trinity, which constitute the main subject matter of this Warning, can seriously disturb anyone. Indeed, these proposals, which are apparently difficult, arduous, since they mobilised the work of six bishops and five theologians are buried in the 20,000 pages and the 6,000 hours of our written and audio-visual productions.

Furthermore, no one would ever have the idea of making blasphemous connections between these theological proposals of our Father and the so-called “immoral behaviours” to which they could lead, unless he had first read the Warning of the Doctrinal Commission not to nourish his soul and spirit, but to wallow his imagination in it. So what is likely to disturb the faithful is not the doctrines of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, but the reading of this Warning made public and accessible to anyone who connects to the cef (Conference of French Bishop) website. In two letters dated June 29 and August 1, 2020, I complained to Archbishop Éric de Moulins-Beaufort of Reims about this publication, obviously to no avail.

I personally have received no reaction concerning this Warning, with one exception, that of the director of an important Catholic educational institution, with whom a few oral clarifications were enough to confirm our several year long-standing relationship of trust. The Warning seems to interest no one! This is where the matter may have rested when, through the Providence of God, the Vicar of Christ chose you for the Church of Troyes.

You are today in the midst of your flock, as the successor of the Apostles, the representative of Our Lord and it is in this capacity that I wish to honour your authority and appeal to your spiritual powers. I will begin by introducing you to Father de Nantes and our Communities, his work and especially what constituted his ‘great affair.’ To this end, I shall strive to tell the whole truth, which alone is capable of reconciling the Holy Family that is the Catholic Church, to which we belong, with the Good Help of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, Mother of every one of us, forever!

SON OF THE CHURCH

In a note delivered during an audience that took place on February 13, 1891, your confrere, Charles-Emile Freppel, Bishop of Angers and deputy of the Chamber of Deputies in Paris, wrote to Pope Leo XIII to adjure him with all his heart to abandon his project of addressing an encyclical letter to the Bishops of France exhorting them to “adhere without ulterior motive to the Republic:”

“Deeply attached to monarchical law, which has been the national and historical law of France for fourteen centuries, I am convinced that the republican form and institutions are in no way suitable for our country, and that they would bring about its religious, moral and material ruin, if they were to take root there in any lasting way. Everyday experience only confirms me in this conviction.” Why? Because, as a matter of principle, “republicans persecute Religion as such, because it is Religion, and because the Masonic lodges, the main centres of republican ideas, have sworn the destruction of Catholicism in France.”

This was so obvious, already, under the presidency of Sadi Carnot, the demonstration of Bishop Freppel so invincible, that Leo XIII, undoubtedly won over to liberalism and perhaps even somewhat to the revolutionary illuminism of Felicité de Lamennais, had no choice but to suspend the publication of his encyclical, which had already been written. He had to wait until the death of the Bishop of Angers, who enjoyed an authority in France that was feared and therefore respected as much by the political authorities, whom he opposed in their anti-clerical projects, as by the French clergy, before promulgating the Letter Amidst the Cares of the Universal Church on February 16 1892. In this letter the Pope made it “a duty for all Catholics to accept the republican fact,” our Father wrote, “in order to merit the promised appeasement and to fight, all united, ‘on constitutional grounds’ for the sole religious cause. The primary duty was to be republican first and foremost, then faithful to one’s faith. The great sin would soon be the ‘sin of monarchy.’ When one does not have the politics of one’s religion, one inevitably ends up embracing the religion of one’s politics.”●

Thus, under Leo XIII’s authority, contained for a time by Saint Pius X, but then relayed by Benedict XV and finally by all the Popes who have since succeeded each other on the See of Peter, the ideology of 1789 was to impose itself in the Church that led its ‘night of August 4’ or, to put it better, its ‘October Revolution’ in Father Yves Congar’s own words, during the Second Vatican Council. This ideological evolution within the Church itself presupposed reprehensible connections with two major doctrinal errors.

First, Modernism, “which perfidiously accords the ‘Christ of faith’ – a personage of no substance and a creation of inner experience and individual sentiment – all the titles that the Church ascribes to Our Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, but refuses them, in the name of reason and critical science, to the ‘Jesus of history.’ This Kantian dichotomy, of consummate hypocrisy, was solemnly condemned by Saint Pius X. It feigns to keep the whole Christian faith, but shift it into the realm of the unreal, the irrational: into nothingness.” Then, the other error, Progressivism, the doctrine of which consists in using the imperfections, slowness and disorders of past centuries as an argument to reckon that the Church is radically unfaithful to the Spirit of Christ and to the inspiration of the first Christians and that the Church’s ancient institutions and her entire tradition should be rejected. Progressivists “prophesy another future, a new age; they demand and prepare for a global reform of institutions, a mystical revolution of the peoples roused by the Spirit, which will open the millennium, the age of the Holy Spirit, the new Pentecost, new heavens and a new earth.”

It is in this perspective of the history of the Church throughout the 20th century that evolves the life and vocation of our Father who was a Child of the Church from the second day of his existence until his dies natalis.

“I was born on April 3, 1924 at Toulon, the son of Marc de Nantes, naval officer, and of Marguerite de Joannis de Verclos. The Left Cartel had just won their laicist and Republican victory on March 11. The Church would condemn Action Française in 1926 and thus free herself decisively from her age-old attachment to the most Christian Monarchy in order to bind herself to this radical-socialist, Masonic regime of the Third Republic. Both my parents were fervent Roman Catholics; both were royalists of Action Française and perfectly legitimist in heart and mind. In my cradle, I found the essence of what were to be my joys and crosses in this life but, I hope, my glory in the next.”●

Following the postings of his father, he was, with his brothers, successively entrusted by his parents to the education of the Marist Fathers of Toulon, the Jesuits of Brest and finally the Brothers of the Christian Schools in Puy-en-Velay. “We have very touching memories of all our old school masters, every one of whom edified us.”● His vocation as a monk-missionary, as a Little Brother of Father de Foucauld dates from 1938, following the screening of the film The Call of Silence. This vocation was to guide his steps to the doors of the seminary in 1943, after having attended the Catholic Faculty of Lyon and spent a year engaged in the Youth Work Camps, thus under the orders and protection of Marshal Pétain. “That was the crucible from which a new, healthy, disciplined and united France was to emerge.”●

HIS YEARS IN THE SEMINARY.

I was at the Seminary of Saint Sulpice at Issy-les-Moulineaux for four years from 1943 to 1947. There I gained a great deal and was perfectly happy: the liturgy was magnificent, the life was well ordered and free from petty constraints and, for those who wished, the studies were at a high level. However, in the wake of the Liberation, Progressivism made its intrusion to be followed clandestinely by Modernism. One evening during the holidays I was telling my mother about this frenzy for novelty which was shaking the Seminary and which was a foretaste of the Conciliar upheaval to come when she said: ‘Anyone who stands against a movement like that will find himself excommunicated.’ Which is exactly what I was thinking too. Then after a short pause she added ‘Whatever happens, don’t let it be you!’ ‘If it is me, it will be your fault,’ I replied. ‘Why so?’ ‘Because you and Papa have always shown me the truth!’ Then she concluded with one of those wise phrases which, once heard, are never forgotten: ‘A tree does not stop the wind that blows in the plain.’●

For the young Georges de Nantes, these four seminary years of intense work and prayer were therefore the time of the first choices and the first struggles to remain, throughout his life, in medio ecclesiae. These years were also a period of preparation for the great controversy that was to impassion the Church twenty years later, on the occasion of the Council.

“I passed my fifth year at the Carmelite Seminary and at the Catholic Institute of Paris. I was ordained priest at Grenoble, which is my diocese, on March 27, 1948 (...). That year I took my Licentiate in Theology and won first prize in the theology competition with a paper entitled “Christ, the Revelation of God.” I think I worked hard and I learned a great deal from our Paris masters, de Broglie, Henry, Danielou, Robert, Arquillières, Andrieu-Guitrancourt…”●

FIRST RUPTURES.

At the end of His seminary, our Father earned a degree each year. “The Licentiate in social sciences with a study on worker priests that allowed me to meet them and about whom I wrote a very alarmist report for Father de Soras. The Licentiate in scholastic philosophy which at the time demanded serious work and exact science. The Licentiate in French literature at the Sorbonne. This literature degree was too glorious to my mind for its real worth. I also prepared two theses at that time. The first one was immense and remains incomplete: it was on the metaphysical structure of the person. The second one, on the notion of person in Saint Thomas Aquinas was ready, but it was rejected by my thesis director, Canon Lallemand, for Modernism!●

Despite these brilliant studies, which offered our Father, if he so wished, the prospects of a legitimate ecclesiastical and academic career, he preferred to put into practice what he would write a few years later to one of his spiritual sons: “Always choose the low path of humility, of prosaic service of God. If you love our Lord as I do, you will detest diversion, distraction, however elegant, however humanistic, however witty it may be! You will go gently and powerfully against the tide, towards the menial tasks, the exiles, the fights that bring no glory. Look at my life! Year after year I am thrown from where I am into a deep pit still less honourable. That is good and it is how we are good workers for the Kingdom of God.”

Thus he would let himself be guided, according to the appointments that were offered to him and the dismissals that were inflicted on him, abiding by the ways of Providence. These ways led him to respond to his vocation of missionary monk in the ‘desert’ of Champagne, today your diocese Excellency, first in the humble and admired service as a country priest in Villemaur, then in a better, more universal, but even more humiliated service of the Church at the Maison Saint-Joseph, in Saint-Parres-lès-Vaudes. Here is how it came about.

“In the autumn of 1948 Father Enne arranged for me to teach philosophy for Father Epagneul, the founder of the Missionary Brothers of the Countryside [Frères Missionaires des Campagnes]. I was required to teach them Thomistic philosophy. I did so with joy, even more so the following year as professor of theology. They were honest, enthusiastic and robust country people. I taught them Saint Thomas and thus immunised them against the Modernism and Progressivism, that their elder brothers, trained at the Dominican Faculties of Saulchoir, in Belgium, had contracted there for life. My students listened to me only too well! Father Epagneul bluntly dismissed me in June 1950, going as far as to forbid me to return to fetch my books and see my students, who were to be led by religious obedience down very different paths.● It was the first dismissal of a long series.

“Having been sent packing by Father Epagneul, I was offered the chaplaincy, in succession to a fellow priest, of the Blind Sisters of Saint Paul and their young boarders. Their convent was adjacent to our Marie-Therese House, on the pleasant country-like Denfert-Rochereau Boulevard, where some priests doing studies were welcomed into the company of the old priests of Paris, among whom Canon Osty shone by his witty eloquence and learning. At number 88 of Denfert-Rochereau boulevard, I approached beautiful souls. Their corporeal blindness made them apt to seize invisible things better than we and to live a loftier perfection. What happiness this gentle ministry was for me!

“During the holidays, I had a parish ministry. In 1948, the Bishop of Grenoble had sent me to Saint Bruno’s church, a large working-class parish. An avant-garde liturgy and pastoral practice were the rule there. Its only apparent tangible effect was to destroy the network of admirable and dynamic works that the previous parish priest, Canon Joussard, had developed ‘under Pétain.’ I went along with everything, but in the summer of 1950, it became unbearable. Their formal refusal of the encyclical Humanis Generis seemed to me irreconcilable with the Faith. I said so; it was not appreciated. Father Bolze, [the parish priest,] said that in the three months of summer, I had demolished their entire year’s work. There was some truth in what he said! It was only too clear to me that their new pastoral methods ended in total and lamentable failure. They begged me not to return the following year. Thereafter I went Saint-André’s and then to Vénissieux, a suburb of Lyons, which was the stronghold of Berliet and of the Communist Party. At Vénissieux I replaced the parish priest who had fallen ill; I would have willingly stayed there, but the parish priest fortunately recovered and resumed his work. I returned to Paris with a heavy heart.●

At the same time, our Father was a contributor to the Action Française journal, entitled Aspects de la France, in which he published articles on religious politics under the pseudonym of Amicus. He, however, had the ‘imprudence’ to give a lecture in Nantes (Brittany) on the m.r.p.,● Conveyor of Marxism! In fact, for the defence of the Church and the truth of the Faith threatened even by political errors, our Father did not hesitate to enter the fray without the slightest consideration for any human respect or the reputation of his own person and of the friends who were willing to follow him. As a result of this conference, our Father was summoned to appear before the ecclesiastical judge of Paris, Canon Potevin, and expelled from the diocese of Paris without consideration or mercy, by Bishop Feltin in person. Second dismissal!

“I had to resign myself to interrupting my contribution to Action Française and my theology thesis in order to return to my diocese. Bishop Caillot wanted to appoint me theology professor at the theological seminary of Grenoble, but a cabal kept me from it. After three months of underhanded tricks, I found myself on the streets of Paris, not knowing to which saint I should turn. My boxes of books cluttered my room at Marie-Thérèse House [the residence for priests in Paris] and I had no destination for them! The reading of my breviary with its numerous psalms of distress was my only solace that summer.

“Finally a devoted confrere – how good and precious are those priestly friendships formed during the long years of Seminary training – rescued me from my predicament by recommending me to the Superior General of the Oratory, Father Dupré, a good and zealous man. He sent me to Father Tourde, the Superior of the College Saint Martin at Pontoise, who immediately engaged me first as Chaplain and then in 1953 as Philosophy Teacher and House Master.”● It was in this college that our Father sought out his first two disciples who were to remain with him for the rest of their lives: Gérard Cousin (our brother Gerard of the Virgin) and Bruno Bonnet-Eymard (yours truly).

THE PROJECT OF A FOUNDATION.

“Years of fullness pass very quickly,” our Father continued. “In 1955, I had a sudden and irrepressible call to satisfy my deepest desire to enter the Carmel, for want of being able to realise my impossible dream. So I left Pontoise, but then the Carmelites reversed their good disposition towards me and refused me entry into the Noviciate. I understand now that that was not to be my path and I thank God for that rebuff, but at the time I was bitterly disappointed. Once more I spent another summer of worry, not knowing what to do with my priesthood in a clerical world growing ever more hostile, where personal dossiers precede you wherever you go accompanied by the snarling of the Christian Democrats, who are fierce as only they know how.●

He continued: “Thanks to the devotion of my admirable friend, ‘the saint of Action Française,’ Henri Boegner, I was employed by André Charlier, who was looking for a Philosophy teacher at the College de Normandie, [near Clères, in the Diocese of Rouen]● where he was Director. I worked for three years with this admirable pedagogue, who was not only an exceptional teacher but also a musician and an actor with the soul of a fighter and a mystic. At the same time I was in charge of Anceaumeville, a small neighbouring country parish with still deeply Christian families. It was for these country parishioners, for some of my former pupils and for the many convents of nuns, where I used to preach, that I wrote the first of the Letters to My Friends, of which sixty copies were sent out on October 1, 1956.”● This circular Letter of spiritual direction would become, through the chain of current events, a true chronicle of the life of the Church in the form of a monthly bulletin with national and international circulation entitled in turn The Catholic Counter-Reformation in the Twentieth Century and He is Risen!

Yet our Father wanted to be a soul hidden in God, entirely abandoned to His divine will and fully occupied with glorifying God, as is revealed by the letter that he wrote to his spiritual director, on All Saints’ Day 1957, of which this is an extensive excerpt

“1 I am ready to do what God wants, indifferently. If I have been attached to political action, this no longer remains in me except in the form of a (weighty) duty. This is the result of ten years – or almost – of priesthood, from failure to dismissal, from dismissal to failure. How I thank God for having saved me in this way!

“2 I have recently received great insights concerning the doctrine of Saint John of the Cross. I see in it the way that remains for me to follow: that of the desire of the most perfect union that can be conceived with my God, my Lord and my All. This desire produces, as far as I am concerned, continual acts of self-sacrifice, and as far as God is concerned, graces of contemplation. Thus, presently I really only think of living on mortification in order to die really to myself, to the world and to the Devil. Love lifts me up. This is possible to my feebleness only by the excessive gentleness and solitude of my present life; I am thus able to pray constantly in the chapel and work on holy things. A swarm of holy souls around me assist me with their prayers and their fervour, which is such an exhorting example!

“3 This being so, what about the future? There is no worry! If someone were to tell me on behalf of God: go there, I would go. Life is of so little importance that I would spend it doing anything in order to please someone.” (Georges de Nantes. The Mystical Doctor of the Catholic Faith.)

“In the meanwhile Brother Gérard, Brother Bruno, and a few others who later abandoned, still desired to be missionary monks after the likeness of Father de Foucauld. At that time, however, everything that seemed to us to correspond to our vocation was tinged with a fair amount of Progressivism and illuminism. Then a Dominican [Father Théry] put an end to our uncertainties by urging us to write a rule in conformity with our vocation and he would have it accepted by a Bishop among his numerous friends. We had become acquainted with this extraordinary – but in no way eccentric – Dominican through his works on the Qurʾān, under the pseudonym Hanna Zacharias, works to which I devoted a detailed review in “L’Ordre Français”. Father Théry had Archbishop Guerry or Archbishop Richaud in mind for our patron but in the end it was Bishop Julien Le Couëdic [one of your predecessors on the See of Troyes, Excellency] who adopted us. At his command I left Normandy and came to Champagne. ‘You will bury yourselves there and later on something will sprout’ were his words to me.

PARISH PRIEST OF VILLEMAUR.

“On September 15, 1958, for the centenary of the birth of Father Charles de Foucauld, we sang the office in the stalls of the church of Villemaur, so permeated with prayerful atmosphere, whose parish priest I had become. The Community was founded!

“For the next five years I spared myself nothing for those three country parishes of Villemaur, Palis and Planty. In the meanwhile, the Brothers pursued their Seminary studies, obtained their licentiates, and did their military service in Algeria, either in combat units or in a Meharist unit as teacher to Touareg children in the Sahara to gain the confidence of the population! Ministering to souls in this part of Champagne where there were great contrasts between valiant Christians and unflinching pagans; assuring the regular publication of the Letters To My Friends, which soon reached a circulation of one thousand and inaugurating our monastic Fraternity, all this filled my life with hard, effective and happy labour. The old supernatural methods of running a parish always paid: prayer vigils for the Men of the Sacred Heart; the five days spiritual exercises with Father Roustand at Paray-le-Monial and Parochial Unions… Father Besançon [the former parish priest of Villemaur to whom our Father succeeded] had traced this path for me: I had only to follow in his tracks. People came back to the practice of their faith; there were vocations and the youth were won over for certain. Providence, with unspeakable delicacy, had given me Mesnil-Saint-Loup, the Shrine of Our Lady of Good Hope as the nearest parish with its holy parish priest for confessor. So many, many graces!

“Everything was going so well that on August 6, 1961, Bishop Le Couëdic, came to clothe the first Brothers and their Prior in the monastic cowl for which we were both most grateful and not a little amazed. This unusual ceremony was a source of great help and consolation to us when later the Pastor’s favour turned to fury against his own.

The Algerian War roused fierce passions as well as admirable dedication. I reminded my parishioners that they had a duty in justice and charity towards their fellow Christians and countrymen, who were at the mercy of the fellaghas’ knives. We had no right to abandon this immense African territory out of cowardice and sloth and hand it over to Islam, then shortly thereafter to Communist barbarity. In the Letters To My Friends I vigorously defended French Algeria as the only morally legitimate thesis. I was one of those very few priests who openly militated against subversion and against the raving anti-colonialism of the clergy, rampant, alas, in Rome too!

“Because of this, one morning, on leaving the church after Mass, I was served with a warrant for a search of the presbytery while being kept in conventional police custody. Several young people of my patronage were arrested. Finally I was confined to a perfectly ridiculous politico-clerical internment in the Major Seminary at Troyes [it has since become a diocesan retreat house, Notre-Dame en l’Isle] in the months of March and April 1962. It was while I was in seclusion there that I heard over the radio, with inexpressible pathos, the retransmission of the fusillade of the Rue d’Isly! Bishop Le Couëdic, however, was passionately Gaullist and over-inclined to respect political power. I could see from his look that I would be promptly liquidated. On March 11, 1963, I received orders to quit the three parishes and the diocese within fifteen days. I managed to procure a six months delay (...).

LOST CHILDREN OF THE CHURCH.

“On September 15, 1963 our Community of Brothers settled, as lost children of the Church, into our Saint Joseph’s House (Maison Saint-Joseph), which we had acquired thanks to the generosity of our friends. Brothers Gérard and Bruno returned from their military service in Algeria and in the Sahara, only to find that, parallel with my misfortunes, they were barred access to the priesthood. ‘We have let one Father de Nantes slip through,’ the Superior of the Carmelite Seminary, Mr. Tollue told them, ‘we are not going to let another one through.’ That was doubtless still pre-conciliar custom. They were not expelled for there was no admissible justification for doing so, but they were not going to be called to Ordination either. So they came to me for good, along with Brother Christian from Villemaur.

“My eviction from the parochial ministry – accompanied by a ab officio suspension, whereby I was deprived of the authority to preach and hear confessions in this diocese that I did not want to leave, that I could not leave – cost me a great deal. Added to that there were absurd vexations such as the constraint to celebrate Mass in the village church before dawn and without singing, as though it were some illegal Mass being celebrated by false monks around a bad priest. The sun ought not to rise on the Church’s shame!”●

AN UNBLEMISHED RECORD

At this stage of this presentation, it is necessary, Excellency, to make certain remarks on the third and final part of the Warning” entitled: “Playing about with language and division.”

It is a succession of statements intended to suggest to the reader that our Father and the Catholic Counter-Reformation have a systematic, general spirit of “revolt,” opposition and rebellion against the “Magisterium.” We can read: “In the texts published by the Catholic Counter-Reformation, taken as a whole, there is an incorrect manner of situating oneself in the Church, before the Magisterium. The Church’s teaching on the truths of the Faith is not accepted religiously, but judged or distorted.” It is even stated: “The Catholic Counter-Reformation has thus made use of more or less real difficulties or inaccuracies in expressions taken out of context, to contest this or that formula and denounce behaviour. It claims to identify contradictions in certain teachings of the Pope, bishops or other priests or theologians. Moreover, it repeatedly affirms like a mantra, that it has never received any condemnation concerning its doctrine and that it has never been found to have been caught out in relation to dogma or the solemn Magisterium of the Church.” Yet just what is the subject of the dispute, the reasons for this opposition between our Father and the “Magisterium?” The Warning prefers to cast a veil of discretion over it. It says nothing about it. Strange indeed!

The Hierarchy, on the other hand is claimed to have shown infinite patience. This is at least what the Warning suggests, by continuing: “Georges de Nantes benefited for years from many clarifications and warnings against his ‘revolt’.” Then the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith had to take harsh measures against our Father and resolve in August 1969 and May 1983 to issue two notifications against him. In them, the Congregation deplores “his revolt against the episcopate of his country and against the Roman Pontiff himself,” thus rendering inadmissible “his accusations against the popes” while regretting “his refusal of the retractions that were requested of him by the Roman authority.”

Unfortunately, the Hierarchy was poorly rewarded for its patience, again according to what is written in the Warning. Thus, faced with Father de Nantes’ alleged inurement in his errors and his revolt, it was necessary to resort to canonical sanctions: a divinis suspension inflicted in 1966 by Bishop Le Couëdic (and not in 1968 by Bishop Fauchet, as is erroneously indicated in the Warning!), then, in 1997, an interdict fulminated by Bishop Daucourt, another former bishop of Troyes. Yet what were the precise motives for these warnings, notifications and censures? Here again, the Doctrinal Commission remains absolutely silent. It is troubling!

When the authors finally reach the end of the Warning, they seem quite at a loss to draw clear, precise conclusions about the Catholic Counter-Reformation which “still defends the same doctrine (...). Today the Catholic Counter-Reformation no longer has a priest and behaves ambiguously in its relationship with its own members and the Catholic Church. Do Catholic Counter-Reformation members in ordinary parishes engage in ideological entryism or are they simply seeking to live their faith? God alone knows.” Then the bishops of the Commission express a feeling of “sadness.” Is that all? Yes, nothing more.

Excellency, how I envy your “sadness,” when we and our friends are filled with a deep sense of indignation over this kind of typical profile, this sort of identikit picture that you draw ex nihilo of our Father as a ‘rebel’ priest. This picture could correspond just as well to Martin Luther, to Hans Küng or to any other notorious or petty rebel that the Church has had to confront. God only knows how many there have been throughout its history.

Thus in the whole Warning, the authors have succeeded in this ‘amazing feat’ of evading the essential question concerning this affair: what our Father had to oppose. The one notable exception was the questionnaire that Bishop Georges Pontier sent to me in April 2019. It had been prepared by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and was to be submitted, under penalty of canonical sanctions, to each of the brothers and sisters in our Communities. What were we asked about? About our doctrine on the Eucharist, the Blessed Virgin and even the Holy Trinity? Absolutely not.

We were ‘invited’ to pronounce ourselves on our submission to the authority of the Magisterium of the Pope and the bishops, but only after having answered this question on which everything depends: “Do you recognise the dogmatic and magisterial authority of the Second Vatican Council, especially in its doctrine on the Church, Divine Revelation, liturgy and religious freedom?” This, in fact, is the whole question for which our Father has distinguished himself and for which he is well known. We, however, are obliged to say that Vatican II, which represents thousands of pages and thousands of hours of lectures and sermons in our corpus, is mentioned only once in the Warning, and even then, only anecdotally, to specify the occasion when Paul VI delivered a speech, from which the Warning quotes only a “fragment of a sentence.”

The ‘great affair’ of the life of our Father, Excellency, which you have ostensibly ignored throughout the Warning can be summarised in a few lines.

Father de Nantes criticised those doctrinal innovations contained in the Acts of the Second Vatican Council that he considered clearly heretical, in particular the social right to religious freedom, at the very time that they were being debated in the conciliar aula. As soon as they were adopted, like a good son towards his father, he hastened to reveal his painful doubts to the Sovereign Pontiff, even going so far as to bring three Books of Accusation of heresy, schism and scandal against Popes Paul VI and John Paul II. While he publicly and firmly opposed this innovative, fallible and reformable teaching, he appealed to the extraordinary Magisterium, so that the Supreme Pontiff himself, i.e. the Church, might restore unity and peace in the name of the Truth of the Faith.

That is what I now need to explain to you in more detail.

“HERESY IS IN THE COUNCIL”

From September 15, 1963, our Father, providentially ‘freed’ from his onerous parish ministry to which he was so attached, launched himself into an enormous battle from Maison Saint-Joseph. He carefully followed the conciliar debates. In the Letters to My Friends, the print run of which was continually increasing, he denounced the intrigues of the progressive wing that occupied the key positions of the Synod, and he supported the Traditionalist Fathers with all his might in an attempt to counter the revolutionary wave that was threatening the Church “in her dogmas and structures.” The sessions followed one another, everything was going at top speed. In this storm, our Father countered the texts that were being discussed in the conciliar aula and were finally adopted with an incredible lucid critique.

Among the answers we made to the questionnaire that had been prepared by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and transmitted to us by Archbishop Pontier on April 15, 2019, we had the opportunity to summarise and make our own the critical study of the Acts of the Second Vatican Council that our Father published under the title Preparing Vatican III in La Contre-Réforme catholique, Volume 4, October 1971 - November 1972, CRC nos46-62. Having received no reply to the memorandum that we submitted to Bishop Marc Stenger on June 13, 2019, I can, in complete tranquillity of conscience, personally expose to you, for your information, Excellency, the critical study of our Father concerning the Second Vatican Council. To this end, I will resume this synthesis that hinges on the four constituent texts of the framework of the conciliar reform. This synthesis compares what seems to us to be in conformity with the Catholic faith and the venom of dei verbum, sacrosanctum concilium, lumen gentium and dignitatis humanae, with regards to the sources of Revelation, the liturgy, the Church and the so-called religious freedom.

DEI VERBUM.

We believe with full certainty that, during His earthly life, the Son of God made man revealed all the divine truth that it pleased the Father to make known to us for our salvation: He thus brought to fullness once and for all, the knowledge that men should have of divine mysteries. The Apostles saw and heard this subsisting, unique divine Word. Inspired very specially by the Holy Spirit for this work, they taught and thus fixed in human language all this life and this doctrine, these divine and historical facts and these spiritual revelations that form the sacred sources and foundations of our religion.

Thus, the Church gives us access to the apostolic Tradition in which we hear and read the Word of God, without any veil other than that of the Faith. The work of the Church herself has consisted of a continuous and faithful “transmission” of this initial Revelation to successive generations. She has fulfilled this mission by translating the original words in accordance with the languages of men, by precisely condemning false interpretations or developments that appeared here and there, by defining and gathering into a corpus of doctrine what the apostolic Tradition taught in a divine manner, no doubt more perfectly, but less adapted to us. The dogmas, liturgical prayer, the Creeds and quite simply our catechism are thus the works of ecclesiastical Tradition, in which we truly and conveniently find God’s authentic Revelation. The Church has done the work well, under the fully solicitous authority of her Pastors and by having frequent recourse to their infallibility.

The Holy Spirit guarantees this zealous and attentive work of the servants of God’s Word: “We must not distinguish between the Church and Jesus Christ, between the Church’s Tradition and Revelation; they are one and the same thing.” (Saint Joan of Arc to her judges at Rouen) It is through this total teaching, through and in her formulas and rites, that the Catholic reaches by means of faith the very mystery of God and achieves union with his Saviour. We can read Holy Scripture, rediscover the teachings and customs of the early Church – this is even recommended – but we will always find therein the same teaching as that of the present-day Church, the same faith, the same truth. Nevertheless, the teaching most adapted to us, the surest, is obviously the faith of the catechism as explained by our good parish priest in keeping with the Church the whole earth over and recapitulating or evoking the teaching of all his predecessors.

No revolution is possible, no historical evolution either, no alteration due to exterior influences, no foreign contribution. If the Church develops her teaching, it is by drawing from her apostolic treasure these new things in keeping with the ancient, without denying or changing anything. On the contrary, it is the apostolic deposit that then seems better known, and the new teaching appears lucidly drawn from the Tradition. Thus, there is nothing nebulous, fanciful, ‘prophetic’ in this Magisterium, and we believe in it precisely because of this fidelity and this lucidity. It itself affirms that no other revelation or divine illumination can contradict it. The teaching of the Church is the Faith, and the Faith is the Tradition through the Church of the Word of God received from Jesus Christ and first taught by the Apostles. It is clear.

Despite some admirable formulas inserted in a deliberately ambiguous text, the Constitution Dei Verbum, intentionally distorted the classic doctrine of Divine Revelation with the aim of freeing itself from the encumbrance of dogma, in the name of Scripture and the ‘vital experience’ of present-day Christians. The Constitution, emancipated from Church Tradition by means of a surprising glorification of Scripture and a presentation of the ‘Word of God’ currently uttered by the men of the Church as though it were a real and contemporary presence of the living and acting Christ, substituted a Word that does not exist personified, structured, or objective in our common experience for the teaching of the Church that had been firm until then.

Here is the result of this thesis that emanates from illuminism: an immense and scandalous confusion of language, the substitution of a hundred opinions for the unique Creed, the crumbling of the Faith. What is more, by order of the hierarchy acting in the name of the Council, the liturgy and catechetics have been systematically renewed in view of a new, informal, immanentist ‘training in the faith.’ The ancient rites and catechisms have been reproved and banished precisely because they preserved the Roman faith in its unchangeable form.

SACROSANCTUM CONCILIUM.

Because the Church is a “mystical person” – the social Body of Christ, the Soul of which is the Holy Spirit –, all that she says and accomplishes is “priestly,” i.e. mediatory of the life and holiness of Jesus Christ “diffused and communicated,” as Bossuet used to say. This function is different and necessarily separated from all other human activities [...]. Thus it is the essential life of Christians of all races and conditions, and of all times, throughout the centuries, from generation to generation. It thus defines a social, Catholic and apostolic rule, which is one and holy, the manifestation of an unchanging faith and the work of an organising Church. Vice versa, once the priestly liturgy has become the normal practice of God’s holy People, it nourishes and maintains the faith, it builds the Church and organises it into a hierarchy. ‘Lex orandi, lex credendi.’ Supernatural life sets prayer in motion, but this movement maintains life. If faith were to disappear, if the Church were to disband, the liturgy would be the first thing to perish. Conversely, however, if the liturgy deteriorates, the Church breaks up and faith is extinguished.

Until the Second Vatican Council, the liturgy was a priestly work, a work of Christ and the Church, more divine than human, a work of preaching, sacramental sacrifice and divine praise, which was celebrated for the spiritual good of the faithful, but not without their pious participation.

After the Council, more often than not, it has become either insipid or a spontaneous, ostensibly aesthetical, modern creation of man who is rendering a cult to himself. Unconcerned with pleasing God and meriting His graces, the postconciliar liturgy is wholly occupied with both pleasing man as though it were an art and meriting that he take interest and participate in it.

That is why the Second Vatican Council itself did not define the liturgy of the future. It was a decisive stage in opening the Church up to novelty. That stage was soon overtaken and it became accepted that ‘obedience to the Council’ meant ‘going beyond’ what had been authorised and in ‘developing’ what it contained in germ. For more than fifty years, there has not been a single heresiarch who has not appealed to the Council in carrying out his action in broad daylight with full immunity. This is especially true in the liturgical domain through all the liberties, orientations and creativity opened up by the conciliar reform, particularly with regard to demolishment of the Mass and the suppression of all Eucharistic ceremonies and devotions.

The true problem is not the rite per se. We are not asking that we be granted a few furtive ceremonies in Latin and the right to make three genuflexions instead of one. We have always recognised that the Mass said according to the Novus Ordo of 1970 is valid.

No, in order to reconcile us, it is a question of being reconciled first of all with God by avenging the insults made to Him officially in the Sacrament of His Body and Blood by heretical theologians and perjured priest.

We can no longer remain insensitive to the sadness of God that deeply moved Francisco of Fatima nor to the pressing request of the Angel of Fatima in 1916: “Eat and drink the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ, horribly outraged by ungrateful men. Make reparation for their crimes and console your God.”

LUMEN GENTIUM.

We profess that this society, the Church, is a human organism or created instrument by means of which God calls all men to salvation and gives them, if they adhere to her through faith, justification and grace for eternal life. Thus, the Church is the means and the source of the true religion, the union of men with the One God. The Church is a Mother who engenders the sons of Adam, through a new birth, to restored grace. She is a family in which divine life is transmitted, beginning with Christ, from generation to generation. The Church is human and divine. Revelation alone makes it known to us in two connected and complementary truths. First of all, the Mystery of the Church is that of a human society of which the Son of God is the human founder and remains the Sovereign Head always living and glorious. He, in fact, governs it Himself with the assistance of a hierarchy that He founded and equipped with His own divine Powers and His rights. It is through Himself, then through His Apostles and through their successors that Christ creates and organises His Church as a social, living, life-giving, holy and perfect Body. The hierarchy is the efficient cause, the created, human, historical and visible cause.

Nevertheless, the union of the human Church with her divine Head is not physical, as in the Incarnation, but moral. It supposes in the Church a holy will, a divine energy, a principle of fidelity that keeps her indefectibly united to her Head. This ‘uncreated Soul’ of the Church is the Person of the Holy Spirit, Who was sent to her on Pentecost by the Father and the Son. The divine Soul of this unique and particular Body, the Paraclete has a profound affinity for this Church, the Catholic Church alone.

Even when He calls all men to the divine Life, it is in subordination to and in view of His one Church. This work of the Holy Spirit is the “formal cause” or the “immanent principle of organisation” of this social Body of which Christ is the Head: that is to say, His Energy descends and communicates itself hierarchically from the Head to the members according to the degrees of the Powers established by Christ. Even where the Holy Spirit acts in complete liberty by the gift of “charisms”, it is neither in contradiction to nor separate from the hierarchical institution and its apostolic discipline.

The Constitution Lumen Gentium perverted this enlightening Catholic definition of the Church.

First of all, it made the Church the light of the world. She is therefore no longer self-sufficient. She is no longer oriented towards the service of God, drawing all men to this superior life for which she alone holds the keys. She is busy, with a passion for the world, for its success, providing it vaguely with an energy said to be divine, a light of the Spirit, a Christlike unction, in order to allow it to attain its complete fulfilment on earth. One could soon come to the conclusion that wherever ‘spiritual’ or ‘cultural’ animation, generosity, liberating struggles take place among men, in a new form, the Church is there.

Then, the Constitution proceeded with a revolution by first presenting the Church as the ‘people of God’ before dealing with the Hierarchy. Thus, the pyramid found itself inverted. The People would have thus pre-existed, and this People is presented, as entirely alive, wholly illuminated and utterly sanctified. It is gathered together by the direct, invisible, disinterested, unexpected, and unlimited action of the Holy Spirit before the hierarchy even remotely intervenes! The entire structure of the Church is overthrown and her boundaries torn down. This people of God goes far beyond the narrow limits of Catholicism and, full of the Spirit, it is adorned with all perfections: all its members are prophets, kings and priests. When thought was finally given to the Hierarchy, there was nothing left to ascribe to it other than a secondary and vaguely antagonistic role. It is put “at the service” of this people of gods!

Moreover, and despite a quickly forgotten Nota prævia, the Constitution Lumen Gentium gave the semblance of having the idea of collegiality triumph, by making the episcopal College the primary factor, the depositary of the “spiritual gift” granted by the Holy Spirit to the Apostolic College. Thus “the collegiate character and aspect of the episcopal order” are asserted. In an extraordinarily ambiguous sentence, the Council makes this College “the subject of supreme and full power over the universal Church.” This was stated with much tact so as to show consideration for the Pope’s authority! With the decree Optatam totius ecclesiæ renovationem, the bishops, who until then had enjoyed a real and personal authority over a limited territory, now exercise an appearance of power without real authority over immense regions and an unlimited universe. This is in direct opposition to the Divine constitution of the Church, such as had been provided for by her Founder, Our Lord Jesus Christ.

Finally, this subversion of the Hierarchy, this new service of the world, has logically resulted in the promotion of the laity to the detriment of the priest who no longer has a specific function wherein he would be irreplaceable, except for the validity of certain sacraments. The real work is left to the laity, of whom he is only and vaguely an animator, an adviser, a bearer of the Word. As a result, there are no more priests, the bishops continually handing them over to the diktats of the laity who are finding themselves with ever more new ministries: conducting funerals, distributing Communion, preaching, and one fine day, they will preside at the Eucharist!

DIGNITATIS HUMANÆ.

We profess that the great apocalyptic combat about which the Revelation speaks to us unceasingly is that of men rebellious to God. They follow the example of Satan, their Prince, whose war cry is: Non serviam, I will not serve! This revolt is the demand for the autonomy of the creature eager to deify himself, to become equal to God by claiming to be free! Eritis sicut dii, you will be like gods. As God enters into the society of men for their salvation, this rebellion would become more aggressive.

In our modern world, the whole tradition of atheistic Humanism and of the Revolution – ‘Satanic in its essence’ – is the refusal of the sovereignty of the God made man, by man who wants to make himself god. The charter of this revolt is the Declaration of the Rights of Man, the substance of which is more metaphysical than political. Its political content aims at attacking our religion and ending with the substitution of the cult of man for the cult of God. Thus, it is normal that the main adversary of the Revolution, more than families and thrones, is the Church, the work of God and Christ among men. This does not mean that the Church has denied human freedom through absolute contradiction of a Revolution that has proclaimed such freedom to be sovereign and employed it against God.

The Church has always recognised that every man has the right and duty to follow his conscience, even if, correctly informed, it is erroneous. The Church knows that “God left man to his own counsel.”● In order to act as men, all must heed their conscience and follow its orders. It is on this interior obedience that God will judge them. Since decisions relative to religion and morality are spiritual works that are a matter for the conscience, no one can be coerced into believing or adopting a moral rule by duress, for what God wants is the assent of the heart. The Church, however, has never defended a conscience that raves.

Even if the duty to follow his conscience is incumbent on each individual, it does not create a social right. As soon as it is a question of life in society, it is no longer the sincerity of the subject that determines freedom but the truth of the action. In every field of social life, it is God Who is the Sovereign Legislator and no one can claim any authority or any right unless he obtains it from God Himself by doing His Will. The Church and the State, acting in accordance with God, in the name of God and for God, cannot recognise any right to the man who is mistaken, whether sincere or not, for it would be tantamount to withdrawing from God a part of His authority and sovereign domain in order to abandon it to His Adversary and to abolishing all objective justice. Nevertheless, a certain “tolerance,” which the Church has always allowed, can be left towards one who is mistaken, in the practice of his error, for the good of peace.

Consequently, social liberty, political as well as religious, which is proclaimed as a human right is, in any event, a crime against God and a delirium, as the Popes – in particular Blessed Pius IX in 1864 in his encyclical Quanta cura – have always declared. For it is both a declared break in man’s subjection to God and a break in the social order, which is atomised by the anarchy of a myriad of individual liberties before being solidified into a Leviathan totalitarianism where the freedom of the strongest places the multitude in slavery. Moreover, the Church has struggled against her own members who claimed that the demand for man’s rights could be reconciled with the rights of the Church, as though one vast whole might be formed by reconciling this better part, the Church’s rights, with man’s. In fact, she cannot accept this reconciliation without renouncing her very essence, and her unique dignity as the one true religion of the One God and Saviour Jesus Christ.

The conciliar declaration Dignitatis Humanæ Personæ, which was adopted following odious manoeuvres, raised the error of a strict and universal right of man and of every human community to religious freedom in the field of civil and social activities to the status of a principle. “Let no one be hindered, let no one be coerced.” The authors of this Declaration were unable to base it on any doctrine or to found it on Holy Scripture, much less on Tradition, as it was completely contrary to both.

With this Declaration, the Church relinquishes her truth, her dignity and her law, in order to recognise that man, every man and states have the freedom that they claim. In this way, it hopes to cooperate in a “harmony” and “peace” of the whole “human family,” which will go beyond the religious differences considered of secondary importance. “In addition, it comes within the meaning of religious freedom that religious communities should not be prohibited from freely undertaking to show the special value of their doctrine in what concerns the organisation of society and the inspiration of the whole of human activity.” (no. 4.) This affirmation of the Declaration means nothing more than a desire to build a fraternal world without basing it on Christ, but with the participation of all human religions and ideologies, fraternally associated. This is the main idea of this Declaration, the guiding idea of a new doctrine that Father de Nantes entitled: Movement for the Spiritual Animation of Universal Democracy (masdu.)

As Father Congar wrote: “Such things cannot be proclaimed with impunity (sic!). Loyalty to what one has proclaimed in this way has many consequences.” Hence, after proclaiming freedom everywhere else in the world, license also entered the Church. Anarchy followed. As this is always accompanied by intolerance, the Pope and the bishops, who have become mere ‘guardians of public order,’ no longer tolerate those who ‘create division’ by rising up against freedom, against their abdication, against their Council and all its ruin. Today in the Church, it is either freedom or anathema!

If we consider the contradiction of the conciliar declaration on religious freedom with all our holy Catholic doctrine and the devastation that has resulted from this novelty in families, in schools, in Catholic nations and in the Church, we must rather seek the inspiration for this plot against God and against His Christ in a wicked, infernal Evil Spirit, the same Spirit who supported the Counter-Church in its obstinate claim in favour of man’s and the state’s rights for Freedom and who finally triumphed at the Council.

The declaration on religious freedom is openly heretical and even constitutes a practical act of apostasy in irreconcilable rupture with the ordinary and extraordinary Magisterium of the Church. It is the focal point of our opposition to the Second Vatican Council. We must now give our verdict on its authority.

ON THE AUTHORITY OF THE SECOND VATICAN COUNCIL.

“Councils have always had the prestige of infallibility in the Church.”● The fact is that they were all convened with the formal intention of exercising the supreme Magisterium of the Faith, “in order to decide wisely and prudently what could contribute to a definition of the dogmas of the Faith, to unmask new errors, to defend, elucidate and develop Catholic doctrine, to conserve and elevate ecclesiastical discipline and to reaffirm morality that had become relaxed among peoples.” That is what Blessed Pius IX wrote in summoning the bishops to the First Vatican Council. The work of a Council was always both dogmatic – the pure divine truth of the Faith had to be declared, uncertainties dispersed and the errors of the time condemned – and canonical – the obligations arising from this Divine truth had to be presented to the faithful for their eternal salvation and in opposition to the maxims of this world.●

Vatican II thus broke with this tradition from the beginning and set out on a completely different path.

On the one hand, it renounced the exercise of its infallible doctrinal power and the canonical power that follows therefrom, in contradiction to what history and theology have taught concerning the unfailing exercise of this extraordinary Magisterium. On the other hand, it turned towards an entirely different work, that of aggiornamento, ecumenism, and opening up to the world – which is an original and vague work. Its real authority and legitimacy, and the degree of divine assistance it can enjoy, are difficult to estimate according to the norms of law. This surprising decision was imposed on the Council by John XXIII on October 11, 1962. It was then that the Fathers learned that they were not to do any dogmatic work, to define divine truths and denounce contemporary errors, nor above all to condemn anyone.

Pope Paul VI confirmed this orientation by adding a notification to the dogmatic Constitution Lumen Gentium, quoting the Doctrinal Commission’s declaration of March 6, 1964: “Taking conciliar custom into consideration and also the pastoral purpose of the present Council, the sacred Council defines as binding on the Church only those things in matters of faith and morals which it shall openly declare to be binding.” Then, on January 12, 1966, thus one month after its closing, the same Paul VI confirmed: “Given its pastoral character, the Council avoided proclaiming in an extraordinary manner dogmas to which the mark of infallibility has been assigned.”

After having renounced to exercise its supreme and infallible authority in matters of dogma and morals, the Council laid claim to a prophetic power of evangelical Reformation in the Church, equal to that of the College of the Apostles, as though it enjoyed the same privileges from which the latter alone benefited to found the Church. It claimed to be pastoral, not to make itself less than the previous dogmatic Councils, but to appear more than them altogether. The first words of the Constitution Dei Verbum clearly show on what this claim is based: the Fathers affirm that they are in direct, immediate and inspired contact with the very Word of God in order to found freely a new Church.

There resulted sixteen texts promulgated in the course of the four sessions of the Second Vatican Council – and all of which are fallible since none of them were declared infallible. The consideration given to each of them differ according to their various titles, their canonical form and their “theological note.” These sixteen texts are controvertible to a greater or lesser extent. It is all a mishmash of Constitutions, Decrees and Declarations. No one knows what Vatican II means. It is everything and nothing, a mixture of the traditional and the novel, the certain and the doubtful, the true and the false, the best being used to endorse the worst. To treat all this as equal to the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed is to decerebrate the Church, to putrefy the Faith by giving it a confused and unintelligible object, one that defies analysis and resists any definition.

Once this analysis was made and published throughout the sessions, what was the duty of our Father from December 8, 1965, the date of the closing of the Second Vatican Council?

Since its Acts were definitively adopted and promulgated by Pope Paul VI, should our Father have submitted, that is, should he have accepted them as being the work of the Holy Spirit, while abandoning all ‘his ideas,’ in a humble spirit of obedience to the Holy Father and to the Council Fathers who approved them with an impressive unanimism of the votes they cast? Should he, in all conscience, with full knowledge of the facts and against the very faith without which one cannot please God, submit to the doctrinal novelties of the Second Vatican Council? It was foreseeable that these novelties would lead the Church along the subversive path of a continual reformation, of an opening to the world inevitably followed by the falsification of dogmas, a radical disorder in the sacred liturgy and the destruction of Catholic morality and law, a total break with the traditional Magisterium? Should he place blind trust in all this?

On the contrary, should he have resisted, opposed this reformation of the Church, in the name of faith, by publicly denouncing it, refusing en bloc all the Acts of the Council? In this case, how far should he take such opposition? Should he have gone to the point of withdrawing from this Reformed Church that is inciting revolt, even if it meant creating a schism?

What had to be done when faced with an alternative such as the one with which our Father was dramatically confronted from December 8, 1965 onward? What would you have done, what will you do, Excellency, in such a situation?

In order to resolve this dilemma, our Father had to undertake something that is the most excruciating to the heart of a well-born son, pervaded by the filial love that governs the whole course of his thought and his life totally oriented towards the “return” to the bosom of the Father, “our most dear Heavenly Father” of Whom the Holy Father is, here on earth, the emanation. This cruel undertaking was the combat of the son against his father!

THE COMBAT OF THE SON AGAINST HIS FATHER

On January 6, 1967, a year after the closing of the Council, in his Letter to My Friends no. 240, our Father was already able to make an “assessment of an insane year” for the Church. An appalling decline in moral standards took place due to the laxity of the laws of natural and evangelical morality initiated by the pastors themselves, a disturbing alteration of the dogma of the faith and a calculated weakening of authority and personal responsibilities within the Church herself.

Yet, when “I arrived at this point in my Letter, in the evening of January 6,” our Father abruptly wrote, “for the first time in ten years the pen fell from my hand. After this catastrophic assessment, I was about to lay out all the documents that confirm it. They prove the reality of the decadence. Day after day since the closing of the Council, they demonstrate the global nature of the movement that is sweeping the Church away” and which imposes this conclusion: “A fundamental compact, a collusion, exists between the highest responsible Authority and the subordinate executors of the reformation with the aim of ‘creating a new Church in the service of the entire world,’” i.e. outside the boundaries of the Catholic, Apostolic and Roman Church.

‘The highest responsible Authority’ within the Church is none other than the Pope himself, Pope Paul VI. Our Father thus decided to publicly denounce the reformation of the Second Vatican Council as a second Reformation after the first one: that of Luther, four hundred and fifty years previously: 1517! “in order to encourage all good men to undertake the Counter-Reformation of the 20th century.”●

To direct this combat, he established two rules; the first, for him and for those of his friends who were willing to continue following him: never to declare that they alone constitute the Church, thus “repudiating this post-conciliar Reformed Church as schismatic and heretical,” the second: to combat “within the Body of the Church, i.e., the visible society in which fallible men conserve the power they have to err or to do wrong, this latent schism this parasitical heresy, this inadmissible novelty that defiles her divine purity and conceals her true life.”●

The first action taken in this combat consisted in addressing “the Sovereign Pontiff as the Supreme Pastor of the Church, and Our Lord Bishops as the legitimate pastors of our dioceses, in person, in order to demand and obtain the resolution of unbearable ‘doubts,’ – ‘dubia’ in canonical terminology – from their infallible Magisterium.”●

“Of course,” our Father added, “we are aware that we are carrying the lamp of our faith in maladroit hands, the flame of Christ’s love in fragile souls. We, nevertheless, conserve the Treasure of the Tradition that has been entrusted to us to be faithfully passed down to the upcoming generation. It is because we believe in the Church that we remain in her, openly fighting against false brethren. It is because I believe in the indefectibility of the Apostolic See that I am going to address the Sovereign Pontiff to ask him earnestly to put an end to the post-conciliar revolution.”●

Our Father sent a “Letter to His Holiness Pope Paul VI” on October 11, 1967. At the very first words, he denounced “The pride of the reformers.” It is a clear and comprehensive presentation of the plan for a certain reformation of the Church – the main idea of both the Second Vatican Council and Pope Paul VI’s pontificate. It aspires to overhaul the Church’s institutions and overthrow her traditions according to the conceptions and desires of men of the Church or of the world today.

Take good note, Excellency, that by sending this letter to the very instigator of this ‘prodigious’ reform, our Father was professing his faith in the Church. Pending her recovery effected by this appeal to her supreme Magisterium, he solemnly warned the Pope that he would beware of this reformation as though of the greatest of sins, because it is “Satanic in its essence, impious in its manifestations and its laws […]. We will differentiate as best we can, according to the infallible criterion of Tradition, that which proceeds from Your customary and Catholic Magisterium in order for us to submit to it, from that which comes from this usurped authority that serves for the Reformation of the Church, which we will always consider null and void.”●

A month later, Father de Nantes published an analysis conducted by a ‘theological study team’ on the encyclical, Populorum Progressio, which described a programme to transform the world, improve the lot of men, establish universal peace, with the participation of all religions and ideologies. This analysis forthrightly raised the tragic question of the Pope’s fidelity to the Catholic Faith. Our Father immediately added extensive quotations taken from Cardinal Journet’s book, The Church of the Word Incarnate, which dealt with the right that the members of the faithful have, to accuse the Pope of heresy or schism and even to go so far as to demand his deposition.●

Why? “Because good Catholics, and they exist at all degrees of the hierarchy as well as among the faithful, are caught in a vice between two temptations which they must resist. They must either accept everything: the chaos and the corruption of liturgy, faith and morals, all of which is ordered or authorised by a unanimous hierarchy headed by the Pope, a temptation to which they are strongly encouraged and constrained to submit! Or else, they must reject everything as a whole because it is all really too stupid, distressing, shameless and pernicious, but in doing so, they forsake a Church that is provoking them into revolt and openly desires their departure. Now these two easy solutions, too easy by far, are sins. One does not forsake the Church of Jesus Christ! Neither does one rally to the Modernist and Progressivist Reformation! So what is the solution? The solution is to reject the Reformation while remaining in the Church. There, however, is no way to dissociate the present Reformation from the Church that is imposing it! Unless… we ‘strike at the Head.’

“… unless we attack the very Person of the Pope, since he, and he alone, stands at the crossroads of these two worlds, those of order and disorder, of Tradition and subversion, of the Work of Christ and the machinations of Belial […]. One can only disobey a Modernist parish priest by invoking, not one’s own faith or individual conscience, but the faith of the Church as embodied in the Bishop. If, however, the Bishop defends his heretical subordinate, one will have to resist one’s prevaricating Bishop by invoking the faith and the discipline of the Roman Church as embodied in the Pope, and appealing to Rome. Yet what if every appeal to Rome should also be in vain? If the Pope should scorn our concern and our indignation? If his obstinate, absolute and terrifying will should uphold those who are demolishing the Church and assassinating the Faith?