Can the Old Testament Be Trusted?

3. The Book of Exodus and Archaeology:

From Egypt to Sinai

The Book of Exodus relates how the Hebrews left Egypt under the leadership of Moses. (Ex 1-15). Having crossed the ‘Reed Sea,’ they arrived by stages at Sinai (Ex 15-18), the holy mountain where God concluded a Covenant with His people (Ex 19-40).

The combined data of archaeology and geography allow us to piece together, with some precision, the itinerary of the Hebrews and to date the Exodus from 2 300 years before Christ. We follow the reconstruction proposed by Professor Emmanuel Anati, since he provides sufficient evidence to identify Har Karkom with the true Mount Sinai.

THE EXODUS IN THE 23rd CENTURY

If they are historical, the events recounted in the book of Exodus must have left traces in the Egyptian texts. It so happens, Anati explains, that “an attentive examination of all texts under the New Empire (1550-1200 b.c.) does not reveal any mention of a flight of Asians from Egypt, or the episode of the ‘Red Sea.’ The behaviour of an army charged with the supervision of the border that lets a group of fleeing slaves pass through [“six hundred heads of household (elef), all the men without counting their families” (Ex 13:37)]” without anything filtering through anywhere? This is at least “a very strange behaviour”!

All becomes clear if we consent to dating these events, not from the 13th century b.c., but from the 23rd, “that is,” he pursues “almost ten centuries before the literary and epigraphic sources on which the specialists of the Bible have always centred most of their research.”

For this period, in fact, contacts are numerous. For example, “in the reign of Pepi I (2375-2350 b.c., according to the date that seems the most probable to us), the Egyptians launched a certain number of punitive expeditions against Asians. A general named Uni immortalised these campaigns against the ‘inhabitants of the sands’ (or ‘Those who are on the sands’) by an account written in the first person, in which he refers to situations comparable to those described in the Book of Exodus.” In his account, however, Uni sings his own praise rather than that of Moses and his God!

The pagan mythologies themselves are influenced by the historical events of the exodus. Anati adds: “It is necessary to emphasise that the parallels between the Pentateuch and Egyptian literature cannot be limited to the time of Moses. Several analogous elements also exist in the Mesopotamian period.”

THE OPPRESSION OF THE HEBREWS

“Now there arose a new king over Egypt, who did not know Joseph. He said to his people: ‘Behold, the people of Israel have become more numerous and stronger than we are. Come, let us deal shrewdly with them, lest they multiply, and, if war befalls us, they join our enemies and fight against us and escape from the land.’ ” (The Book of Exodus 1:8-10)

An echo of this concern can be found in Egyptian texts dating from the reign of Pepi I (2332 - 2283 b.c.), that is, exactly in the right times according to the new dating: “In the delta region instability and violence reign, and foreigners have become the masters [...].” This is a clear allusion to foreigners who had become landowners.●

THE VOCATION OF MOSES

“And when she [Jochebed, Moses’ mother] could hide him [Moses] no longer she took for him a basket made of bulrushes, and daubed it with bitumen and pitch; and she put the child in it and placed it among the reeds at the river’s brink.” (The Book of Exodus 2:3)

Sargon, founder of the city of Akkad, Mesopotamia, around 2300 b.c., attributes to himself the same adventure: “My mother, the high priestess, conceived me; in secret, she gave birth to me. She put me in a basket of reeds, which she covered with bitumen, she sealed the lid. She pushed me into the river, which did not rise above me. The river carried me away and passed in front of Akki, the water carrier [...] Akki (adopted me) as his son (and) raised me...”●

Who copied whom? According to traditional chronology, it was the Bible that copied the Mesopotamian legend, a thousand years later. Everything changes, however, if we adopt the new chronology!

We find another story parallel to the story of Moses’ flight●, in Egyptian literature this time, in the 20th century b.c.: a popular account also portrays a high official named Sinuhe, who must flee his native land and, like Moses, go into exile.

“Now Moses was keeping the flock of his father-in-law, Jethro, the priest of Midian; and he led his flock to the west side of the wilderness, and came to Horeb, the mountain of God.” (The Book of Exodus 3:1)

L’événement capital de la théophanie du Buisson ardent eut lieu « à la montagne de Dieu : l’Horeb », nous dit le texte. Les exégètes ont longtemps pensé que ce nom de “ montagne de Dieu ” lui était donné par anticipation. D’après eux il se serait agi d’une montagne ordinaire, devenue ensuite seulement “ montagne de Dieu ” parce que Dieu y avait conclu son alliance avec son peuple.

The major event of the theophany of the Burning Bush took place “on the mountain of God: Horeb,” the text tells us. The exegetes have long thought that this name of “mountain of God” was given to it in anticipation of this event. According to them, it would have been only an ordinary mountain that subsequently became the “mountain of God” because it was there that God had concluded His Covenant with His people.

This is an error! Emmanuel Anati with his team discovered that Horeb, (or Sinai, i.e. Har Karkom) had been in the past, a great centre of worship and pilgrimage, a sacred mountain for the people of the desert.

In 1992, the unearthing of a Palaeolithic “sanctuary”, about forty thousand years old, proves that “its [the mountain’s] religious function is far from being simply limited to the Bronze Age; this is attested by a succession of multi-millennial events and traditions, making this mountain one of the most ancient sanctuaries known, [and even] one of the first evidences of human religiosity.”●

Jethro, a Midianite priest, introduced his son-in-law Moses to this mountain of Horeb, which was already sacred to the Midianites.

“The angel of Yahweh appeared to him [Moses] in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush; and he looked, and lo, the bush was burning, yet it was not consumed.” (The Book of Exodus 3:2)

The botanists from the team of Emmanuel Anati inventoried the vegetation of Har Karkom. It happens that one can find, scattered here and there, rtam bushes more numerous in the rocky gullies on the edge of the plateau. A certain variety, which resembles our broom, reaches two metres in height.

“I [God] will be with you [Moses]; and this shall be the sign for you, that I have sent you: when you have brought forth the people out of Egypt, you shall offer worship to God upon this mountain.” (The Book of Exodus 3:12)

On his way to Egypt, Moses stopped again at ‘the mountain of God’ where he found Aaron, who had come to meet him on God’s command.● The mountain was therefore located on the road to Egypt that Moses was to take, on the border of the Midianite territory of the tribe of Jethro. Har Karkom meets these requirements.

THE PLAGUES OF EGYPT

The staff of Aaron

Among the numerous rock engravings that decorate the “mountain of God”, one represents a crook next to a serpent that resembles it. According to the ideograms to the left, it is the graphic illustration of the staff of Aaron, which transformed itself into a serpent●, the instrument of the marvels by which Moses brought forth his people from Egypt. (...)

“At midnight Yahweh smote all the first-born in the land of Egypt, from the first-born of Pharaoh who sat on his throne to the first-born of the captive who was in the dungeon, and all the first-born of the cattle.” (The Book of Exodus 12:29)

William G. Dever, professor of archaeology and anthropology of the Near East at the University of Arizona, explains that many of the “plagues” correspond to evils to which the Egyptians were accustomed; periodic infestations of frogs, bats, flies and locusts (plagues 2, 3, 4, and 8), and epizootic diseases decimating herds (plague 5) are not rare in these regions, today as in antiquity; serious meteorological perturbations with sudden floods, hail storms, dark clouds (plagues 7 and 9), characterise the harsh climate of the eastern Mediterranean. As for the ulcers (plague 6), they can be compared to an infection known and treated under the name of subcutaneous leishmania, caused by a parasite transmitted by sand flies.

Dever adds, however, that the last plague, (the death of all the first-born male Egyptians) cannot be explained scientifically: “No known epidemic could be so selective.”● This last plague shows that behind all the others, it was indeed God Who intervened and directed these natural disasters against the Egyptians.

THE CROSSING OF THE SEA

“ ‘Tell the people of Israel to turn back and encamp in front of Pi-hahirot, between Migdol and the sea, in front of Baal-zefon.’ You shall encamp opposite this place, by the sea. For Pharaoh will think: The children of Israel are wandering to and fro in the countryside. The wilderness has closed in on them.” (The Book of Exodus 14:1-3)

The place names define with precision a place of encampment and an itinerary.

“Pi-hahirot” (1) refers to an overflow, located on the coast and discharging its water into the Mediterranean sea. Although traditional exegesis persists in indicating a route directed to the south of the peninsula (towards Saint Catherine’s Monastery), this name of Pi-hahirot suggests another direction. It does not lead to the Red Sea, but to the Mediterranean Sea.

“Pi-hahirot” (1) refers to an overflow, located on the coast and discharging its water into the Mediterranean sea. Although traditional exegesis persists in indicating a route directed to the south of the peninsula (towards Saint Catherine’s Monastery), this name of Pi-hahirot suggests another direction. It does not lead to the Red Sea, but to the Mediterranean Sea.

“Migdol” corresponds to one of the control posts where there was one of the Egyptian garrisons controlling the road along the north coast. A multitude on the run could not have passed through without being both spotted and stopped. That is why God did not make His people take this road.

“Baal-zefon” (2) was located on the lagoon that borders the Mediterranean. This lagoon was a former branch of the great delta of the Nile where rushes, reeds, and swamp bushes abounded, whence the name of “Reed Sea.”

Pursued by Pharaoh, the Hebrews thus embarked on the trail marked out along the barrier beach, which looks, even today, like a ford, in the middle of the sea. It is actually a long and narrow band of land, composed of a series of dunes and rocks. Even modern jeeps get stuck! This helps to imagine the Egyptians who got stuck in the mud:

“Yahweh so clogged their chariot wheels that they could scarcely make headway.” (The Book of Exodus 14:25)

At certain points, the costal tongue of land sinks somewhat under water. Some places are reputed to be dangerous because of the presence of quicksand.

“As the water flowed back, it covered the chariots and the charioteers of Pharaoh’s whole army which had followed the Israelites into the sea. Not a single one of them escaped. The people of Israel, however, walked on dry ground through the sea, the waters being a wall to them on their right hand and on their left.” (The Book of Exodus 14:28-29)

The “Red Sea” has no connection with the account. Firstly, because the Biblical expression must be translated “Reed Sea.” Rushes and reeds do not grow in what we call the Red Sea, to the south of Suez. Furthermore, the account does not speak of shoals, but of a dry, unbroken causeway, flanked to the right and to the left by the sea, that the Hebrews travelled over dry-shod.

Thus, the army of Pharaoh was rendered powerless by the conditions of the terrain, while the tribe on foot, charged with its goods, herding livestock, counting in its ranks old people, women and children outdistanced its pursuers.

Of course, Anati dispenses with a divine intervention. So when it comes to the cloud and the darkness that prevented Egyptians and Hebrews from meeting, he thinks he can interpret: “It seems to mean that the Hebrews knew the way, while the Egyptians were wandering in the dark.” The text, however, says something altogether different! The same applies to the conclusion of this pursuit; it must be admitted that the Egyptian army was not annihilated by a natural cause:

“Yahweh said to Moses: ‘Stretch out your hand over the sea, that the water may come back upon the Egyptians, upon their chariots, and upon their horsemen.’ ” (The Book of Exodus 14:26)

We imagine this tidal wave very well: just think of a tsunami. With this difference: here there is no natural explanation, no earthquake, but only the hand of Moses stretched out over the sea, and Yahweh gazing on the Egyptians, sowing confusion in their army.

THE CROSSING OF THE DESERT

Emmanuel Anati managed to rediscover the itinerary followed by the Hebrews. Here we give only one example, that of Marah (3):

“When they came to Marah, they could not drink the water of Marah because it was bitter; therefore it was named Marah. The people murmured against Moses, saying: ‘What shall we drink?’ And he cried to Yahweh; and Yahweh showed him a piece of wood, and he threw it into the water, and the water became sweet. There Yahweh made for them a statute and an ordinance and there he proved them.” (The Book of Exodus 15:23-25)

This site, (El Mura today), is an oasis of greenery, in the middle of the dreary expanse of dunes. The rare wells furnish brackish, undrinkable water. The abundant vegetation, however, shows that the roots of the plants reach an underground sheet of fresh water. It suffices to read the above text to be able to identify the location!

Another well-known episode is that of the manna:

“In the evening quails came up and covered the camp; and in the morning dew lay round about the camp. And when the dew had gone up, there was on the face of the wilderness a fine, flake-like thing, fine as hoarfrost on the ground. When the people of Israel saw it, they said to one another: ‘What is it? [man hūʾ] ’ For they did not know what it was. And Moses said to them: ‘It is the bread which Yahweh has given you to eat.’ ” (The Book of Exodus 16:11-15)

Nowadays, quail land by thousands in their migration season in the north of Sinai. “On a day in May 1984,” relates Emmanuel Anati, “I witnessed a similar shower of migratory birds on Har Karkom. Entire groups fell, exhausted by fatigue and the terrible heat.”● As for the manna tamarisks (tamarisk mannifera) that grow in the bed of wadis, Anati explains that they are covered with yellow flowers with fleshy petals, very edible, that the Bedouins call “manna”. The wind often blows them off in great quantities.

In order to complete this possible explanation of the prodigy put forward by the archaeologist, let us add that one would however seek in vain a natural cause for this daily supply of food falling exactly on the place of camp of the Hebrews, and in sufficient quantity to feed them all!

How many Hebrews were there? Archaeological data provided by Anati and his team offer a partial answer to a passage of the broadcast “The Bible Unearthed” where some contributors laughed to scorn the number of Hebrew fleeing from Egypt: “The Biblical account refers to six hundred thousand men under arms, which would undoubtedly represent two million souls in all. Can you imagine two million people leaving a country as big as Egypt that only counted three and a half million inhabitants? That would have provoked an economic and social collapse from which the Empire would never have recovered.”

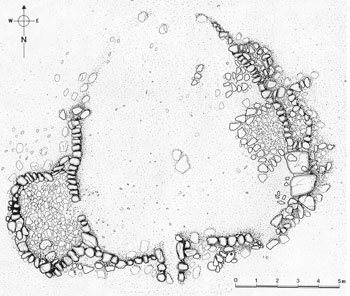

In reality, if we refer to the Hebrew text, it is translated thus: “The sons of Israel set out from Rameses to Soccoth, in total, six hundred elef on foot – all men – not counting their families.” (The Book of Exodus 12:37) Now, elef, in Hebrew, means “thousand” but also “heads”! That is to say: six hundred heads of families. In terms of numbers, this corresponds indeed to the “five hundred and eighty-three habitations,” the plan of which archaeologists have been able to reconstruct, from the “vestiges of the structures,” that are at the foot of Har Karkom. But that is not all. At the foot of this mountain, archaeologists have uncovered other clues. (...)

These are excerpts from Can the Old Testament be trusted? A reply to the programmes of the television channel Arte: The Bible Unearthed, He is Risen, no. 45, May 2006.

According to Emmanuel Anati, quoting Esodo, tra mito e storia, 1997, p. 246

Quoted by Emmanuel Anati, Esodo, tra mito e storia, 1997, p. 248

The Book of Exodus 2:15

When Pharaoh heard of it, he sought to kill Moses. But Moses fled from Pharaoh, and stayed in the land of Midian; and he sat down by a well.

Emmanuel Anati, Les mystères du mont Sinaï, p. 10-11

The Book of Exodus 4:27

Yahweh said to Aaron: “Go into the wilderness to meet Moses.” So he went, and met him at the mountain of God and kissed him.

The Book of Exodus 7:8-12

8 And Yahweh said to Moses and Aaron: 9 “When Pharaoh says to you: ‘Prove yourselves by working a miracle,’ then you shall say to Aaron: ‘Take your rod and cast it down before Pharaoh, that it may become a serpent.’” 10 So Moses and Aaron went to Pharaoh and did as Yahweh commanded; Aaron cast down his rod before Pharaoh and his servants, and it became a serpent. 11 Then Pharaoh summoned the wise men and the sorcerers; and they also, the magicians of Egypt, did the same by their secret arts. 12 For every man cast down his rod, and they became serpents. But Aaron’s rod swallowed up their rods.

William G. Dever, Aux origines d’Israël. Quand la Bible dit vrai, Bayard, 2005, p. 25, translated from Who Were the Early Israelites and Where did they come from?

Emmanuel Anati, The Mountain of God, p. 157