THE HOLY SHROUD OF TURIN

Supporting articles

AN IMAGE NOT MADE BY HUMAN HANDS

THE “ SYDOINE ” OF THE LORD

Constantinople, August 1203. Robert de Clari, a knight from Picardy, contemplates in the Church of Our Lady Saint Mary of Blachernae, the “ sydoine ” of the Lord, which is stood “ upright ” every Friday “ si que on i pooit bien veir le figure Nostre Seigneur “ (so that the figure of Our Lord can clearly be seen).

“ Figure ” signifies not only the face, but the form of the whole body. The following year, the Crusaders ransacked the city and “ nul ne seut on onques, ne Griu, ne Franchois, que li sydoines devint quand la vile fu prise ” (no one ever knew, neither Greek nor French, what became of the Shroud when the city was taken) (The Conquest of Constantinople, 42).

Two years before, Nicolas Mésaritès, guardian of the relics kept at Saint Mary of the Pharos, the “ sainte-chapelle ” of the imperial palace, recalled the mysteries of Christ’s life perpetuated by the presence of the relics in that place: “ Here He rises again, as shown by the Shroud and the cloths [...]. They are of linen (apo linou) [...]. They withstand corruption, for they wrapped the ineffable Dead Christ, naked and perfumed, after the Passion. ”

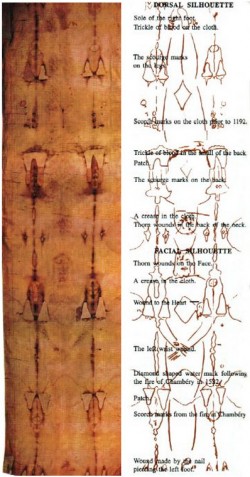

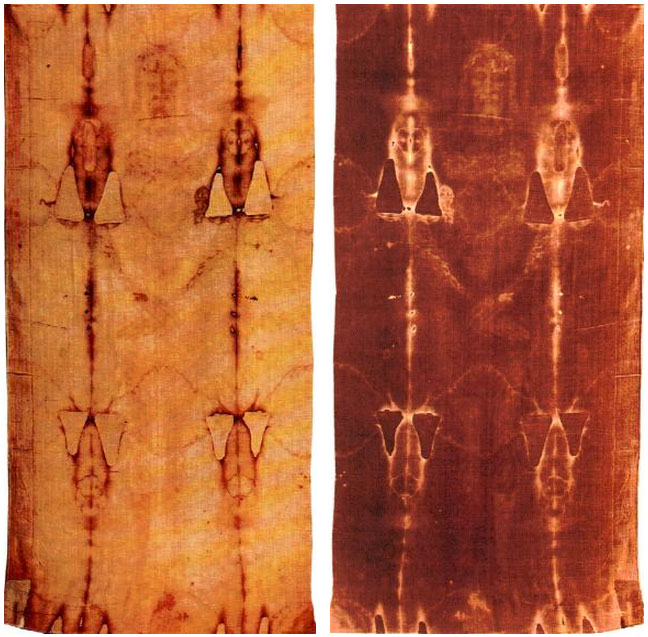

The Holy Shroud now kept in Turin, a herring bone weave “ linen ” cloth, is this same Relic, marked with the imprints of the “ naked, ineffable Dead ”, Jesus Christ Our Lord, shrouded in this cloth after having been “ perfumed ”. In the middle of the Cloth, two Body imprints are distinguishable, meeting at the heads without, however, touching. One is of the front image of the Body and the other is of the back, inverted as though in a mirror.

The explanation is quite simple: at the moment of entombment, the Body of Jesus was laid on its back over half the length of the Shroud, which was then pulled down over the head and over the front of the Body down to the feet.

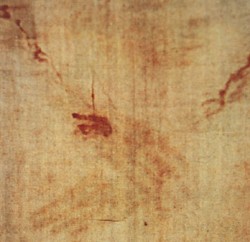

The Blood which flows from the wounds in the hands, the feet and the side, trickling into the small of the back, forming droplets on the forehead and the nape of the neck is indeed, in visible light, the colour of “ dried blood ”, as Barbet had observed in 1933 when the Holy Shroud appeared on the steps of the Duomo; a “ crimson ” colour noticed by Brooks in September 1978.

On the other hand, it loses its colour under ultra violet rays: “ Highly absorbent. No colour. Fluorescent edges around certain zones ”, notes Pellicori. Which is in agreement with the laboratory data where the blood as a whole shows a total absorption. These fluorescent borders associated with blood flows, as well as the numerous flagellation marks, powerfully suggest, therefore, the presence of blood serum.

Confirmed by the chemistry of the micro-traces taken from the surface of the Cloth: “ The blood stains are composed of haemoglobin and also react positively to the albumin test. ”

THE PHOTOGRAPH OF JESUS

THE DIVINE SURPRISE

Turin, May 1898. On the fringes of an exhibition of sacred art, the Holy Shroud was displayed above the high altar of the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist. A Salesian from Provence, the thirty seven year old Don Noël Noguier de Malijay, one of the first French Salesians to have been admitted to the noviciate by Don Bosco himself, was absorbed “ in meditative contemplation, as all were inspired to do by such a wonderful testimony of the Passion and Death of Our Lord Jesus Christ ”, as he himself relates.

He was at that time a teacher of physics and chemistry at the international high school of Valsalice. He continues: “ But besides pious thoughts, I soon developed a scientific preoccupation (you will forgive a science teacher for such a thing) concerning the authenticity of the famous shroud. That is why I meticulously examined every slightest detail of this double imprint of Our Lord’s Body, which stood out sufficiently from this cloth, despite the effect of time, together with the numerous scorch marks left on the Shroud after a fire and stains resulting from tests applied in the Middle Ages, and which no painting could have withstood. ” The fact that the image has remained stable through fire and water and reagents capable of changing any colouring, sums up to this day the specific chemistry of the image and constitutes an “ ongoing mystery ”.

The research programme to come later is already drawn up in the questions which the young and learned Salesian put to himself: “ 1. What is the nature or, if you like, the chemical or physical cause of the impression of the strokes that have reproduced and preserved the image of the divine Saviour? 2. Is this image positive or negative? ”

A surprising question, which inspired Don Noguier, “ from the very first day of the solemn exposition, with the idea of having the Holy Shroud photographed ”. He will recount later how this idea occurred to him – an idea which we can regard as the most brilliant intuition of the century. Looking through a pain of powerful binoculars, he noticed that “ the body reliefs were of a darker shade, whereas the deep set or receding parts were of a lighter shade; it did not take me long to compare the image of the Shroud to some kind of negative photograph. Long conversant, moreover, with photographic art, it quickly occurred to me that a photographic reproduction of this extraordinary document would yield interesting results. That is why I congratulate myself today on having been among those who then exerted themselves to have the Relic photographed, despite a certain opposition which was happily overcome. ”

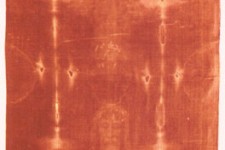

Secundo Pia was merely the one designated by the King of Italy to carry out this idea of Don Noguier (during the night of May 28 to 29, 1898). Besides, he was not the only one, nor even the first. Don Noguier, “ foreseeing that he would be able to obtain directly on the photographic plate a positive image of Christ ”, had already taken photos which verified his intuition: from the semi-darkness of the background of the cloth, light in reality, made dark through photographic inversion, there appeared, luminous, the perfect positive image of a real human body of athletic beauty.

THE THIRD DIMENSION

Not only is the image a negative, but it registers the body relief. Using a volunteer who had allowed himself to be draped as the Holy Shroud was draped, Jackson and Jumper studied experimentally the relationship between the body-cloth distance, on the one hand, and the intensity of the image, on the other. The hypothesis of an inversely proportional relationship, the mathematical formula of which would allow the body’s natural volume to be reconstituted, was found to be unequivocally verified one day, in a way that was quite unexpected, by Bill Mottern working on the VP8 in 1976. Further proof of authenticity, renewing the surprise of Don Noguier’s photo, in so far as everybody had forgotten that it was another Frenchman of genius, Gabriel Quidor, Don Noguier’s contemporary, who had already formulated and verified this hypothesis seventy years before.

Thereafter, the facts are there, excluding the idea of a false shroud of Christ having been fabricated in the Middle Ages. Before 1898, no one had seen the real and true image of the Body of Jesus crucified, His admirable Head and His incomparable Face, as the photographic inversion, the negative, shows here. All anybody had seen were these mysterious brown stains on the linen cloth, but only positively, and without the benefit of photography, stains which, taken as a whole, define an enigmatic and disturbing silhouette of a supine human, wounded moreover, killed and wrapped bleeding in this shroud.

THE HOLY SHROUD OF LIREY

Not long after the capture of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204, the Holy Shroud was removed to Athens. The following year, the nephew of the emperor Isaac II Angelus complained about this to Pope Innocent III, demanding among all the treasures stolen from his uncle, “ who is holy ”, the relics, and “ among them, the most sacred object of all, the Shroud ” which is presently “ at Athens ” (1205). The Shroud then passes into the possession of the Charpignys, a noble Franco-Greek family of Morea. Agnes de Charpigny, Dame of the Vostitza, the wife of Dreux de Charny, eldest brother of Geoffroy, Lord of Lirey, brought this “ saincte relique ” to France.

Thus, after having sojourned in the East for twelve centuries, the Holy Shroud was shown for the first time in the West in Champagne, by the canons of the collegiate church of Lirey, founded by Geoffroy de Charny.

As is recognised by the anonymous archive document known as the “ Mémoire de Pierre d’Arcis ” (1389), “ far from being restricted to the kingdom of France, [the news] spread throughout the whole world, as it were, so much so that from every point in the universe, masses of people flocked ” [to see it] in a vast upsurge of faith and devotion, comparable to what was seen in 1978 and to what we shall see again tomorrow: an exposition lasting forty-three days drew three and a half million pilgrims, filing past the sacred Relic non-stop.

Diocese of Troyes, Saturday May 28, 1356. By letter duly signed and sealed, given in his palace of Aix-en-Othe, his summer residence, Henri, elected to and confirmed in the episcopal see of Troyes since 1354, grants the noble knight Geoffroy de Charny, lord of Savoisy and of Lirey, “ approval, authority and decision ” in the “ divine worship ” celebrated in the collegial church by the said Lord, in so far as, the bishop adds, “ we have been informed by the legitimate documents ”. You will search in vain for this piece in the voluminous archive files published by Ulysse Chevalier. It does not figure there at all.

This approval was again confirmed by a bull of indulgence dated the 5th June 1357, co-signed by twelve bishops, addressed to all the pilgrims visiting the said church and venerating the relics to be found there, reliquias ibi existentes.

A pilgrimage medal, a sort of lead medal worn by pilgrims in the Middle Ages, now kept at the Musée de Cluny, provides unquestionable proof that the Holy Shroud figured among the said “ relics ”.

It represents two figures vested in copes – whose heads have disappeared – holding the Holy Shroud full length as though they were taking it from its reliquary, itself struck on the right (on the left for the reader) with the arms of Geoffroy de Charny, who met his death at the battle of Poitiers on September 19, 1356.

We shall not be surprised to see this great swell of fervour giving rise to a furious polemic, as witnessed to by the “ Mémoire ” attributed to Pierre d’Arcis, Henri de Poitiers’ successor in the episcopal see of Troyes; document dated... 1389! A close study of these distant events, gives one the inescapable impression of dealing with “ something known ” ; like a repetition, six hundred years in advance, of the events of the 20th century. Even the dates coincide!

1356 : we are in the years following the Holy Year of the Jubilee for 1350, which drew immense pilgrimages to Rome, where the “ Veil of Veronica ” was venerated. The faith was so alive in those times that any evocation of the Passion of Jesus caused a stir. And so these crowds did not move out of curiosity, but out of devotion, of tender compassion for the sufferings of our gentle Saviour, for the grief of His Mother the Virgin standing at the foot of the Cross.

In 1350, on the threshold of the modern age, effigies of the Holy Shroud in fact renewed the effect of the stigmata which the “ Poverello ” of Assisi had displayed in his own flesh in the previous century.

Jesus was an athlete: the facial imprint allows His height to be evaluated at 1.80 m; and His build allows His weight to be evaluated at 80 kg. When in full health, Jesus must have radiated an extraordinary charm, the revelation of which has been reserved to our times of photography. Before then, painters and mosaic artists took as their model this inexplicable and unaesthetic imprint, copying it positively, even if it meant interpreting it (cf. for example, the Holy Face of Laon, reproduced in CRC n° 237, Eng. ed., p. 22; Christ the Pantocrator of Daphni, CRC n° 217, Eng. ed., p. 11, the Holy Faces of Genoa and of the Vatican, ibid., p. 12, the Christ of Sinai, CRC n° 237, Eng. ed., p. 9; the umbella of John VII, ibid., p. 10). It is an untenable contradiction to claim that this vague body form might itself be a work of art produced, in some way or other, with the impossible intention of making it appear positively, through photography, as the imprint left by Jesus on His Shroud.

Jesus was an athlete: the facial imprint allows His height to be evaluated at 1.80 m; and His build allows His weight to be evaluated at 80 kg. When in full health, Jesus must have radiated an extraordinary charm, the revelation of which has been reserved to our times of photography. Before then, painters and mosaic artists took as their model this inexplicable and unaesthetic imprint, copying it positively, even if it meant interpreting it (cf. for example, the Holy Face of Laon, reproduced in CRC n° 237, Eng. ed., p. 22; Christ the Pantocrator of Daphni, CRC n° 217, Eng. ed., p. 11, the Holy Faces of Genoa and of the Vatican, ibid., p. 12, the Christ of Sinai, CRC n° 237, Eng. ed., p. 9; the umbella of John VII, ibid., p. 10). It is an untenable contradiction to claim that this vague body form might itself be a work of art produced, in some way or other, with the impossible intention of making it appear positively, through photography, as the imprint left by Jesus on His Shroud.

On the one hand, it is a fact that the copyists of modern times, from the 16th to the 19th centuries, thinking that they were dealing with the positive image of the body of Jesus Christ imprinted on this Shroud, arranged things so as to free it from its vagueness, feeling their way towards its... negative which will not appear until 1898 (cf. for example, the epitaphios of the cathedral of Smolensk, reproduced in SS II, p. 101).

On the other hand, any supposed mediaeval forger would have had to work backwards, starting from an individual copied, sculptured or traced positively, in order to end with something ghostly, disturbing and incomplete (cf. Joe Nickell’s scumble, reproduced in SS I, p. 93!)... unacceptable to the Church, meaningless and repulsive for the devout, but powerfully traced and done so as to appear, through the invention of photography, as an incomparable image of Jesus Christ? It is impossible.

What do we see on this image? The ugliness of the suffering servant (Is 53), or the beauty of the most beautiful of the children of men (Ps 45)? The Fathers of the Church are divided. The question is renewed again today. Penetrating the depth of the mystery of the Redemption, the Abbé de Nantes constructs an admirable “ aesthetic of the Holy Shroud":

“ We have here a man of great physical beauty. Tall, well built, muscular, of athletic virility, showing the full form of this perfectly developed being. We still have to eliminate the defects in the linen cloth to see this slender height and the magnificent bearing of the head. If we go into detail, we notice the finesse of the shoulders, the wrists, the elegance of the hands made to seem even longer by the thumb being retracted in the hand.The Face is magnificent: of an immense serenity, a gentle and humble majesty. The brow is wide and open. The eyebrows are very firmly drawn, the nose imposing and the head is long.This Body and this Face are those of a Leader. ”

And yet He has chosen to leave us this photo of His ugliness, the image of Him “ whose look was as it were hidden ” (Is 53. 3), who is like a worm (Ps 22) in the act of His Passion: the body naked and torn apart, the chest raised, the face puffy, the lips swollen and tight, as though bursting. But it is an ugliness that is beautiful “ because it speaks of virtue, of sacrifice, of heroism, of suffering willed out of love for us, for our redemption ”. It is the dramatic aesthetic of the sorrowful mysteries.

Furthermore, for one who is not put off by this ugliness and who carries on in a vigorous act of faith, the height of beauty is revealed: “ It is beautiful like a dissonance evoking the things of the hereafter. “ Hyperbolic aesthetic of the glorious mysteries: “ This Holy Face suddenly radiates a goodness which streams from the fold of the eyelids. The very noble, very open and radiant brow prevails over the faults of the lower half of the face and the burst lips. It shines with the glory of God. The very beautiful sweetness of a call to love falls from these lips being presented for a kiss. Ecce sponsus, ‘Behold the bridegroom’. Thus has God loved. ”

THE HOLY SHROUD OF CHAMBÉRY

1453 is the year when Constantinople was taken by the Ottoman Turks. In retrospect one shudders to think what would have become of the Holy Shroud had the Crusaders not removed it from there in 1204! Or rather: let us admire the ways of Providence...

In that year, Marguerite de Charny, granddaughter of Geoffroy, made a gift of the Holy Shroud to Duke Louis of Savoy and to his spouse Anne de Lusignan. At first, these princes attached the notable Relic to their portable chapel. Regarding it as a palladium, they took it with them wherever they went: to Bresse, to Piedmont, to Savoy and to Switzerland. Then from 1502, they entrusted it to the canons of the collegiate founded by the Duchess of Yolande, sister of Louis XI, and her spouse the Blessed Amadeus IX, to be kept in the chapel of the castle of Chambéry, to which Pope Sixtus IV granted the title of “ Sainte Chapelle du Saint Suaire ”, with indulgences and privileges. In his treatise De sanguine Christi, this Pontiff claims for the Linen Cloth “ the homage and adoration due to the Cross by virtue of the divine Blood with which it is stained. ”

There then begins an era of public veneration for the “ Holy Shroud of Chambéry ”, which will last for two centuries, the scale of which is difficult for us to imagine today. It has to be said that the Church encouraged it with all her authority; the approval of the Sovereign Pontiffs was added to the official favour shown by princes. In 1506, Pope Julius II authorised public devotion to the Relic by means of a Bull wherein he designated it as “ the notable shroud in which Our Lord Jesus Christ Himself was wrapped in the tomb ”. He fixed an annual feast day for the Holy Shroud, with a proper Mass and office, to be kept on May 4, the day after the feast of the Finding of the Holy Cross. He also claimed for the Relic the honours due to the Cross, that is to say, veneration and adoration. According to this maxim which fell much later from the lips of the Blessed Valfré of the Oratory (1629-1710), chaplain to Duke Victor-Amadeus II and his spouse, Anne of Orleans:

“ The Cross receives the living Saviour and gives Him back dead; the shroud receives the dead Saviour and restores Him alive. ”

The Holy Shroud is shown to crowds of pilgrims twice a year: on May 4 for the feast and on Good Friday. These solemn expositions will witness immense crowds of pilgrims from every social class: kings, princes, lords, burgesses and village people. In 1516, François I, whose devotion to the Holy Shroud was due to his mother, Louise of Savoy, came to Lyons on pilgrimage, with all his court, on foot, clothed in an alb, as an act of thanksgiving for the victory of Marignano.

1516 is also the year when Marguerite of Austria ordered an artist, whose identity is a matter of controversy, to paint a copy of the Holy Shroud, which copy is now kept in the Church of Saint Gommaire, at Lierre in Belgium. It is the first of a long series of such copies, which are now very useful, not just as a record of the history of devotion to the Holy Shroud, but more especially to illustrate all the blunders which a “ forger ” would inevitably have made, from the Renaissance to the 19th century, as indeed during the Middle Ages and at any time...

In 1532, during the night of December 3 to 4, a raging fire broke out in the Sainte Chapelle of Chambéry. One of the canons saved the silver reliquary, as the metal was already beginning to melt. The irradiation of the red hot metal, and no doubt a few drops of molten silver spilt on to the corner of the folded linen inside, burned it. Consequently, when the cloth was unfolded, there were as many scorch marks as there were folds in the linen cloth. The water thrown over the cloth to put out the fire left those diamond shaped marks with the burnt edging, which we see along the whole length of the longitudinal axis: they too follow the order of the folds as does the symmetry of the scorch marks. By what miracle did the two silhouettes remain safe, in the middle of the Sheet, framed by the two scorch lines!

The following year, 1533, the damaged Holy Shroud was not displayed for May 4, and rumour immediately spread that it had disappeared. We find an echo of this in Rabelais, where Gargantua is made to say:

“ When Brother John set about punishing the miscreants who were picking the monks’ grapes, some made a vow to Saint James, others to the Holy Shroud of Chambéry. But it burned three months later, so much so that not a single shred of it was saved. “ A barefaced lie, but one that at least testifies to the popular custom of invoking the “ Holy Shroud of Chambéry ” on a par with Saint James.

The Protestants swore a particular hatred for this devotion. Calvin is venomous: “ When one Shroud has been burned, they always find a new one the next day. They said it was indeed the same one as that of the day before, which had been saved from the fire by miracle; but the painting was so fresh that the lying availed nothing, if there were eyes to look. ”

Pope Clement VII set in progress an official recognition of the Relic. Then the Holy Shroud was carried in procession to the convent of Saint Clare where it stayed for fifteen days. Whilst praying, the Poor Clares knelt and sewed patches into the areas that had been burned, then backed the Holy Shroud with a length of Holland cloth to reinforce it. And on May 2, 1534, the Relic was returned to the Sainte Chapelle, to the sound of all the bells ringing in the town. A witness wrote:

“ There were a great many pilgrims who came from Rome, from Jerusalem and from several other distant countries. ” Thus it can be stated that the Holy Shroud of Chambéry was Christendom’s principal pilgrimage destination at that period.

THE HOLY SHROUD OF TURIN

September 14, 1578, the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, the Holy Shroud makes its entrance into Turin, become the capital of the House of Savoy, greeted by artillery salvos. Duke Emmanuel-Philibert had had it transported on men’s backs, over the mountains, at the time of the pilgrimage of Saint Charles Borromeo, Archbishop of Milan, who came to fulfil a vow that he had made in answer to his prayer that his diocese be delivered from the plague.

The holy archbishop, escorted by a small group of priests and members of his household, left Milan on October 6. During the whole journey, covered on foot, the pilgrims meditated on Our Lord’s Passion, recited the office and prayers, and sang canticles. Saint Charles Borromeo’s entrance into the Piedmontese capital, to the booming of canon and harquebus, was triumphal. The following Sunday, the Holy Shroud was displayed publicly in the square of the palazzo ducale.

The Relic never returned to Chambéry, and that was a further Providential arrangement. For two hundred years later, the Sainte-Chapelle of Chambéry will be ransacked by the French troops of the Revolution.

The 17th century marks a sort of apogee with the devotion brought to the Holy Shroud by Saint François de Sales. “ The copy of this sacred effigy was his favourite image, wrote Msgr. Camus, Bishop of Belley, his friend and neighbour. He had it in embroidery, in painting, in oils, in line engraving, in illumination, in half relief and engraving. He put it in his bedroom, in his chapel, in his oratory, in his study, in his living room, in his gallery, everywhere. ”

"It is the country’s shield, the holy bishop would say; it is our great Relic... Certainly, I have a particular reason for being devoted to it, for my mother dedicated me to Our Lord, when I was in her womb, before this holy standard of our salvation. ”

This was an allusion to the exposition of July 21, 1566, at the collegiate church of Annecy, Notre Dame de Liesse; Françoise de Boisy, who was only fifteen years old, kneeling beside her pious husband, thirty years older than herself, whilst contemplating with tearful compassion the bleeding effigies of her Saviour, had asked Him that the child she bore might be a boy and that this son would become a priest. A month later, she gave birth to a son, her first born, the future François de Sales.

That is why this saint had a life long devotion for this Relic, the devotion of the predestined, imprinted with tender compassion and full of love. We find this gently expressed in a better he wrote to Saint Jeanne de Chantal, dated May 4, 1614 (see below).

Less is known of the devotion of the Blessed Sebastian Valfré for the Holy Shroud, and his zeal for spreading it. He considered that an exposition was as good as a homily. He wrote to the Duke: “ Oh! how much it said, even though it did not speak when Your Royal Highness approached the Sacred Cloth to kiss it. It will certainly have offered your soul peace and will have declared war on sin. May God grant us the grace of being struck in our hearts by such a rare sermon so that they remain with Jesus Christ, in the hands of Him to Whom all human hearts belong, especially those of princes and kings. ”

Duke Emmanuel-Philibert had ordered in his will, in 1580, the construction of a church for the safe keeping of the Relic. More than a hundred years had to pass before this project was realised – a project that would never have seen the light of day without Valfré’s constant appeals: “ I feel impelled to beg Your Royal Highness to have the chapel of the Holy Shroud completed as a matter of urgency. Because I ought not to resist such an impulse, I tell it to you, hoping that you will construct an even more magnificent chapel in your heart. ” (Cesare Fava, Vita e tempi del Beato Sebastiano Valfré, Torino 1984, p. 265-268)

Finally, on June 1, 1704, the Relic was transferred to the chapel built in the apse of the cathedral by the Theatine father, Guarino Guarini.

THE DEVOTION OF A PREDESTINED SOUL

Annecy, May 4, 1614.

Whilst waiting to seeing you, my very dear Mother, my soul greets yours with a thousand greetings. May God fill your whole soul with the life and death of His Son Our Lord!

At about this time, a year ago, I was in Turin, and, whilst displaying the Holy Shroud to such a great crowd of people, a few drops of sweat fell from my face on to this Holy Shroud itself. Whereupon, our heart made this wish: May it please You, Saviour of my life, to mingle my unworthy sweat with Yours, and let my blood, my life, my affections merge with the merits of Your sacred sweat!

My very dear Mother, the Prince Cardinal was somewhat annoyed that my sweat dripped onto the Holy Shroud of my Saviour; but it came to my heart to tell him that Our Lord was not so delicate, and that He only shed His sweat and His blood for them to be mingled with ours, in order to give us the price of eternal life. And so, may our sighs be joined with His, so that they may ascend in an odour of sweetness before the Eternal Father.

But what am I going to recall? I saw that when my brothers were ill in their childhood, my mother would make them sleep in a shirt of my father’s, saying that the sweat of fathers was salutary for children. Oh, may our heart sleep, on this holy day, in the Shroud of our divine Father, wrapped in His sweat and in His blood; and there, may it be, as if at the very death of this divine Saviour, buried in the sepulchre, with a constant resolution to remain always dead to itself until it rises again to eternal glory. We are buried, says the Apostle, with Jesus Christ in death here below, so that we may no more live according to the old life, but according to the new. Amen.

Francis Bishop of Geneva.

May 4, 1614.

(Oeuvres complètes, édition d’Annecy, 1910, t. XVI, p. 177).