The Federal Government

and the Indians of Western Canada

AFTER the scandal of the residential schools, which rebounded on religious communities, it is important to have a precise idea of the government policy that presided over their foundation. James Daschuk’s thesis, published by Les Presses de l’Université Laval under the title La destruction des Indiens des Plaines (= The Destruction of the Plains Indians) mercilessly brings it to light.

Initially undertaken to discern the causes of the health inequalities between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in western Canada, it analyses “the material conditions that, determined by economic and environmental forces,” have led to the present disparity. In the end, however, it corroborates the theses of Maureen Lux and Mary-Ellen Kelm who, as early as the 1990s, scientifically explained the decline of Aboriginal populations by the racism of settlers and government policies.

The first chapters, which are already very interesting, examine the ebb and flow of tribes in the Northwest as soon as the fur trade began, especially from the beginning of the 18th century. The author shows that the annihilation of some tribes while others expanded their territory was due to epidemics caused by diseases unintentionally transmitted by Europeans to the native population, which was not immune, and to the demands of trade: “The invisible hand of the market had a palm full of germs which, as imperceptible as it was to the naked eye, would nevertheless transmit deadly diseases and an unprecedented hecatomb on the Plains. Between 1730 and 1870, several epidemics devastated the Canadian Northwest. It was not until the first vaccination campaigns that their transmission from generation to generation was stopped and their impact mitigated.”

The first chapters, which are already very interesting, examine the ebb and flow of tribes in the Northwest as soon as the fur trade began, especially from the beginning of the 18th century. The author shows that the annihilation of some tribes while others expanded their territory was due to epidemics caused by diseases unintentionally transmitted by Europeans to the native population, which was not immune, and to the demands of trade: “The invisible hand of the market had a palm full of germs which, as imperceptible as it was to the naked eye, would nevertheless transmit deadly diseases and an unprecedented hecatomb on the Plains. Between 1730 and 1870, several epidemics devastated the Canadian Northwest. It was not until the first vaccination campaigns that their transmission from generation to generation was stopped and their impact mitigated.”

The thesis makes little mention of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate who began their apostolate in these vast regions in the mid-19th century. James Daschuk notes that the Hudson’s Bay Company, the owner of these territories, accepted their presence when it saw its advantage. The Catholic missions, coupled with schools, health centres and training centres for trades and agriculture, settled the converted populations. They thus played an essential role in preserving the natives, until the establishment of reserves.

WHEN CANADA TOOK OVER THE NORTHWEST TERRITORIES

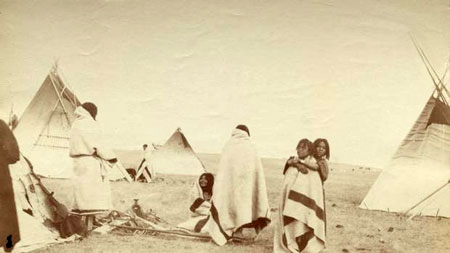

Everything changed with the arrival of the federal government, as James Daschuk will show. Indeed, since 1850, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s hold on its territories had loosened considerably: colonists arrived and settled practically wherever they wanted, while the native populations, struck by the depletion of the buffalo herds, were to fall victim to five successive epidemics in twenty years: influenza, smallpox, scarlet fever and whooping cough.

In 1864 and the following four years, the crops were devastated for various reasons. In 1868, a general famine ravaged the whole of Western Canada, to the point that an international relief campaign was launched with the help of the Canadian government. The unfortunate starving people never saw a single penny of it: Ottawa allocated the amounts collected to finance the construction of a road linking Lake Superior to Red River. In fact, Prime Minister Macdonald, who coveted these territories, thought that the Company would hand them over to him all the more easily if the relief expenses were more onerous to the Company than the profit that the territories could yield. Thus it was that in December 1869, Rupert’s Land and the North West Territories fell under Ottawa’s jurisdiction.

The Company’s agents lost their authority, but the government had not yet installed its officials. While the Métis of Red River rebelled against the land-surveying of their property, the southern Plains, now Canadian, became a haven for bandits of all kinds fleeing the United States police! For more than a year, violence took hold of the region.

The Company’s agents lost their authority, but the government had not yet installed its officials. While the Métis of Red River rebelled against the land-surveying of their property, the southern Plains, now Canadian, became a haven for bandits of all kinds fleeing the United States police! For more than a year, violence took hold of the region.

Then a new smallpox epidemic broke out. The Hudson’s Bay Company was no longer there to monitor the progress of the epidemics through its network of posts and to organise vaccination campaigns, and the Canadian government, which knew that these plagues were frequently ravaging the population, had made no plans to curb the disease.

It was not until October 1870 that a Board of Health was set up to take the necessary measures. It was a little late: the epidemic caused 3,500 victims, and the toll would have been even higher without the dedication of a doctor of the Company, Dr. McKay, who travelled the entire region between the Athabasca and Saskatchewan, and without Oblate Fathers Petitot and Seguin, who vaccinated 1,700 people in the Mackenzie River basin.

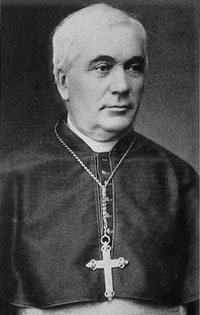

James Daschuk reports on the heroic attitude of the missionaries during this epidemic, especially Bishop Grandin: “At Fort Carlton, Vital Grandin, Catholic Bishop of Lac La Biche, went from tent to tent trying to bring some comfort to the sick. He had no medicine to combat the plague, which simply took its terrible and often deadly course. He heard the dying in confession, placing his head close to theirs to listen to their exhausted murmurs of pain and repentance. Many asked him for baptism before they died.” In fact, the mission diary records two thousand baptisms for that summer of 1870.

“The bishop also accompanied one of the sick employees, although Protestant, because his pastor had not come. James Nisbet, the long-awaited pastor, chose not to go to the fort for fear of contaminating his small community in Prince Albert when he would return.

“Grandin’s intervention at Fort Carlton and Nisbet’s refusal to go there illustrate the respective strategies of Catholic and Protestant missionaries in the face of the epidemic. (...) In the Protestant missions, the order to disperse was often given at the first rumours of contagion, even before the epidemic had arrived in the region. (...) In contrast, Catholics closed ranks in the face of the ordeal. The Métis communities that grew up around the Catholic missions in Alberta experienced extremely high mortality rates in the summer of 1870. Thanks to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s quick and effective intervention, the disease took very little toll on Fort Edmonton. A little further away from the palisades, the situation was quite different: only ten kilometres from Edmonton, the Métis community of Saint Albert had a population of about 900; the disease spread to two-thirds of the population and caused 320 deaths.”

However, James Daschuk is honest enough to supplement this reflection with an excerpt from the Butler Report, named after the British officer of the Red River Expeditionary Force, who was sent to evaluate the extent of the epidemic: “The reluctance of the Catholics to disperse the population may not entirely explain the high death rate in the communities under their care. (...) “However,” Butler indicated, “the serums purchased at Fort Benton and used in Saint Albert at the height of the epidemic ‘were not what they claimed to be.’ ” That is evident!

The Board of Health, which intervened too late, still tried to justify its existence, but it did not want to take into account the results obtained by Dr. McKay or by the Oblates who had acted without its authorisation. It therefore decreed a sanitary cordon around the contaminated areas, even though they were no longer contagious, which deprived them of all supplies just at the beginning of winter. In some regions, such as Saint Anne mission, famine once again followed the epidemic.

A WAR NARROWLY AVOIDED

Obviously, all these upheavals were close to provoking a general war by the natives against the new arrivals, whom they accused of all the evils. The Catholic missionaries spared the region from this third plague, thanks to their influence on the great Cree chief, ‘Sweetgrass’, a recent convert. This led to the idea of signing treaties between the Dominion and the natives.

However, their negotiations were biased. For the latter, it was a question of having their property rights recognised in the face of the ever-growing number of colonists. For the government, on the other hand, it was a matter of stalling for time and buying peace in a way that would allow it to eliminate as soon as possible its interlocutors, whom it considered to be the main obstacle to the economic development of these vast areas.

A first treaty was signed in 1871. Its conditions applied only to the territories east of the Red River. Others followed, zone by zone towards the West. In 1873, the Liberal Alexander Mackenzie succeeded the Conservative Macdonald, but kept the same Indian policy.

To negotiate each treaty, the government waited until the tribes, even more weakened, were on the verge of revolt. One by one, their means of subsistence disappeared: the buffalo, the Hudson’s Bay Company shops that were closed to them because it no longer bought furs, the job of rower on barges now that steamboats were multiplying on the lakes.

Tensions rose in 1873-1874. In the autumn of 1874, the signing of Treaty 4 at La Qu’Appelle did not go well: the three thousand Natives gathered there were certainly half-starved wretches, but they were well aware that their weakness was being exploited, so they refused to smoke the ceremonial pipe.

The government’s intention was to settle them in the reserves, but without giving them the means to become real farmers. The famines therefore continued, while tuberculosis began to take its toll: from 1880 onwards, it was the leading cause of death in the reserves.

CONDEMNED TO STARVE TO DEATH OR TO DISAPPEAR VOLUNTARILY

It took the victory of the Sioux against the American army in 1876, in which General Custer was killed, to convince the Canadian government to quickly sign Treaty 6 with tribes that were already very much weakened but still capable of joining the ranks of the Sioux. At the same time, and because it was more intent than ever on getting rid of this threat, it hardened its policy.

The negotiator began by refusing to include in the treaty a commitment to provide food aid in the event of famine or epidemic, on the pretext of not turning the natives into an idle population; as if they had the will to be always hungry and sick. Eventually he reversed his decision, but when the Cree asked for free medicine, he replied that “a medicine chest will be kept at the home of each of the Indian agents in case any of you should fall ill.”

James Daschuk shows that during the period 1877-1882, the government responded to the famines “in a way that was tailored to further its own development projects in the West by subjugating malnourished and increasingly disease-ridden Aboriginal populations.”

In Ottawa, Alexander Mackenzie was doing everything he could to evade the pressing demands for food aid. He refused to allocate funds on the grounds that it was the responsibility of local authorities, who had no resources!

Faced with the tragedy that was unfolding, some local officials, such as Lieutenant-General Morris, took it upon themselves to buy cattle and distribute them to the natives. They were dismissed from their functions!

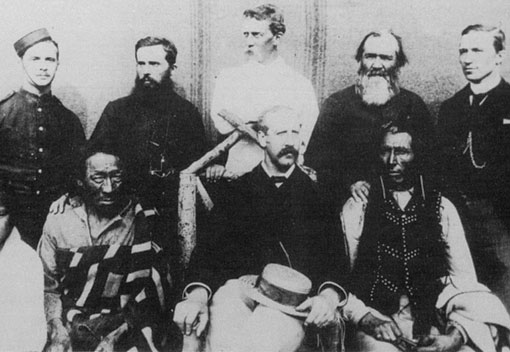

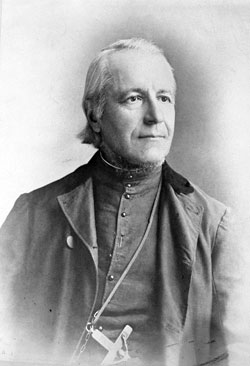

Prime Minister Macdonald

In October 1878, Macdonald returned to power where he would remain until his death in 1891, and the Conservatives continued to rule the country until 1898. They were therefore the ones primarily responsible for what followed, even though they acted with the agreement of the Liberal Party.

An old friend of the Prime Minister’s, Dr. Daniel Hagarty, was appointed Medical Superintendent of the Northwest Territories in 1878. In this position, he did extraordinary work, to which James Daschuk pays tribute, eradicating smallpox from the Canadian Northwest. He was therefore a competent man, too competent for his friend’s taste! When, in 1880, he noticed the outbreak of tuberculosis in all the Indian tribes and wanted to implement an effective policy to reduce it, he was purely and simply recalled to Ottawa and his post was abolished.

It was the distribution of beef that caused the epidemic. Indeed, the disappearance of the buffalo herds was compensated by the importation of huge herds of cattle from the South, in particular from Texas. Over a period of twenty years, more than ten million head were transferred, as well as a million horses. Unfortunately, among them were frequently cattle infected with bovine tuberculosis, which can be passed on to humans through the consumption of infected meat.

This happened all the more easily because the Indians consumed it in the same way as buffalo meat: raw or dried. The mortality rate in 1880, 1881 and again in 1882 was catastrophic. Thousands of people died, especially in the south.

Macdonald understood perfectly well the advantage he could take of the situation in order to build his transcontinental railway “without human obstacles,” unlike our neighbours to the south, who had to contend with continuous fighting with Indian tribes.

Yet there was little risk for Canadians. All the reports of the Mounted Police and the various officials responsible for setting up the reserves were unanimous until 1881 in their surprise at the extraordinary submissiveness of the natives. There were hardly any cases of theft of cattle or horses, even though the Natives were starving. There were certainly gatherings of people near the forts or government shops, but always peaceful, far from the stereotyped image of savages to be pacified.

In fact, already at this time, many were converted, and all understood that following the disappearance of the buffalo, they no longer had their usual means of subsistence. Agreement with the government was a matter of survival for them. What they did not imagine, and neither did their missionaries, was that the government did not want their survival, but their disappearance.

An example: Macdonald, who was personally in charge of the Department of Indian Affairs, had decreed that food assistance would only be given in exchange for work. This could be justified, but he did not plan for any work to be given to the Indians. Or again, he claimed that he was turning these semi-nomads into farmers, but there were neither sufficient training staff nor seed grain.

In cases of serious need, Macdonald conceded the distribution of food, but never of clothing or blankets, when the Indians had nothing left to make them for lack of buffalo. Touched by compassion, some officials took it upon themselves to provide them with these goods. One of them protested to the Prime Minister: “When the government has to spend $1000 to accomplish what $10 would suffice to accomplish today, it will understand that it has been sleeping on a volcano.” When one thinks of the millions the federal government spends today on Native assistance, perpetuating the neglect of the past while claiming to be repairing it, it is fair to say that this public servant was perceptive.

In 1881, Macdonald took advantage of the first brawls involving loss of lives to further reduce food aid, the savings being used to finance the defence of government warehouses.

On January 2, 1882, following a rumour that the government was deliberately starving the Blackfoot, a black market deal involving a head of beef and some offal went wrong and sparked an armed confrontation. It was the end of more than ten years of good relations between these tribes and the Mounted Police.

Despite this, the government did not release a single additional dollar. The Liberal opposition felt that the Conservatives were still doing too much, and accused them of “squandering public funds.”

Despite this, the government did not release a single additional dollar. The Liberal opposition felt that the Conservatives were still doing too much, and accused them of “squandering public funds.”

It was finally decided that the army would distribute the food, with the instruction: “Use discretion in the distribution of food while exercising the utmost restraint.” Contrary to the provisions of the treaties, food assistance was granted only to the natives living on the reserves.

The Mounted Police, considered too favourable to the Indians, were placed under the authority of the Department of Indian Affairs; from then on, they would enforce its policy mercilessly.

This is how Macdonald had achieved his goal: the land was free for the settlers and the railway, since the natives were parked on the reserves and the recalcitrant ones would starve to death. In August 1883, the first train reached Calgary without incident, and two years later, Vancouver.

This did not prevent the Indian populations on the reserves from being undernourished and increasingly ill. Indian aid was further reduced in 1883 on the pretext that wheat yields were good; true, but there were not enough mills to make flour. In 1884, a very submissive and hard-working Indian received 150 grams of flour per day, which was considered preferential treatment!

Let us quote the testimony of Father Cochin: “I saw the children arrive at my house to be taught, naked, emaciated, and dying of hunger. These poor little ones came to the catechism and to school, despite a cold of 30 to 40 degrees below zero, their bodies barely covered with a few rags with holes in them. It was a pity to see them. The hope of having a small piece of good dry cake, probably more than the desire to learn, was the motive for the cruel sacrifice they imposed on themselves every day. Many of them died from deprivation.”

During the 1880s, the food that the Hudson’s Bay Company shipped by river often arrived at the reserves several months late; it was spoiled but distributed anyway.

Nevertheless, the operating budget for the reserves exploded. In 1880: $157,572.00; in 1882: $607,235.00, thereafter nearly a million dollars a year. This was obviously due to the corruption of officials and suppliers. Until the rise of agricultural capitalism, supply contracts were the real engine of the commercial economy in the West.

Gradually, an American company, Baker, which enjoyed the status of a transnational corporation, which exempted it from customs duties, monopolised the supply contracts, finally supplanting the Hudson’s Bay Company. Its owners were generous donors to the Conservative Party in Ottawa, as they were to the inhabitants of the White House.

The fundamentally racist reserve system was dominated by Macdonald’s relative, Lawrence Vankoughnet, who knew virtually nothing about the realities of the North West, which he visited only once, shortly after the opening of the railway. He showed a maniacal determination to cut back on the expenses of the Department of Indian Affairs, of which he was the most senior official. On one occasion he decided that assistance would be reserved for “Indians who show a disposition to manage on their own.” On another occasion, he simply abolished the custom of exchanging gifts, etc.

He went so far as to calculate the minimum ration for their survival, or to decide that a sick Indian could be given medicine as prescribed by the doctor, but not food.

THE REVOLT OF 1885 AND ITS CONSEQUENCES

Such treatment could only lead to violence. From 1882 to 1885, there were a few spontaneous incidents, which, moreover, were never aimed at the police or civil servants who were showing humanity. In 1885, however, the Indians, especially the Cree, joined the Métis revolt. In April, some settlers and two Oblates, Fathers Fafard and Marchand, were massacred at Frog Lake by two young Cree warriors who accused the missionaries of having betrayed them.

We know how Macdonald put down the revolt ruthlessly. For fear of reprisals, many Indians left the reserves. Tracked down, many rebels preferred to commit suicide rather than fall into the hands of the White.

Even bands that surrendered were severely punished, especially the Cree. Deprived of lawyers, some of the accused were sentenced to death by public hanging as an example. Prime Minister Macdonald approved of these practices, which “must teach the Redskins that the White man is in charge.”

In Eastern Canada, newspapers nevertheless reported on the mistreatment of which the Indians were victims. The scandals were quickly hushed up. In Parliament, the government acknowledged that there had been fraud, but only “from time to time.” Macdonald peremptorily declared on July 13, 1885: “This, however, cannot be considered a fraud on the Savages, for they are merely living on the benevolence and charity of the Dominion, and as the old saying goes, beggars can’t be choosers.”

When the explosion of venereal disease in the West also became a major public health problem, the cause had to be exposed: the prostitution of Indian girls and the sale of barely pubescent girls to whites for $10. It was then that Hector Langevin, the brother of the Bishop of Rimouski, refused on behalf of the government to consider this practice as trafficking in women, on the pretext that “according to the thinking of the savages, marriage is only a market and a sale, and the parents of a young girl are always on the alert to find her a buyer.”

It is fact that, from that time onwards, the murders of Indians and especially of Indian women were never the object of investigation, let alone prosecution.

After the revolt of 1885, the Ministry decided to break up the tribal system. Several chiefs, even moderate ones, were imprisoned for futile reasons. On the reservations, land was allocated and exploited individually, and all commercial exchanges were subject to authorisation; an efficient way to prevent the Indians from integrating into the local economy.

In short, the whole life of these populations was completely disorganised. Several bands went into exile in the United States where they were not treated any better.

Finally, the completion of the railway allowed the beginning of a massive colonisation of the West and the arrival of new waves of contagious diseases, such as influenza and measles, in addition to chronic tuberculosis. The native population of the Plains then reached its lowest demographic level: between 1885 and 1889, it dropped by about 50% and stabilised at around 15,000 people, all of whom were subject to the Department of Indian Affairs.

THE CATHOLIC MISSIONARIES,

THE ONLY DEFENDERS OF THE NATIVE POPULATIONS

Let us now turn to the notorious residential schools run by the Catholic Church and the Protestant denominations, where many children were taken away from their parents, civilised by force, often brutalised and sometimes even assaulted. If the complaints for the most despicable acts concern mainly the establishments managed by Protestant pastors, it does not prevent the opprobrium from falling on the Catholic Church, which is accused in particular of cultural harassment.

All the above suffices to make us understand that these compulsory educational institutions, created by Macdonald, had the same intention. This is enough to exonerate the Church from infamous responsibility, especially since it was, on the contrary, the only one to oppose the Prime Minister’s ambitions and then to seek a way to mitigate their devastating effects.

It is true that the missionaries eventually agreed to take charge of part of these establishments, just as they had endorsed the principle of reserves; but did they have a choice? To refuse was to abandon their faithful there, with no one to do them any good and make their condition less harsh.

James Daschuk is honest enough to point out that many Indian families were able to escape starvation or confinement on the reserves because they had received basic education in the schools. They were thus able to exchange their legal status as Indians for that of Métis or even forgo government assistance altogether.

Today, it is easy and profitable to accuse the Catholic residential schools of cultural genocide, as if they were responsible for the abandonment of the Aboriginal way of life. This upheaval, however, is actually only the consequence of the total disappearance of the buffalo. In fact, the day when the Indians were able to obtain horses and rifles, they embarked, despite the warnings of the Oblates, on an unbridled hunt for buffalo, the dried bones of which would be transformed into fertilizer. Within a few years, the herds had disappeared and the traditional way of life became impossible. The residential schools were in no way responsible for this, neither were the reserves, and even less so the missionaries. The arrival of the settlers completed an evolution that had begun earlier because of the Indians themselves.

It must also be acknowledged that the settlers’ way of life attracted many natives, without regret. Among them, those who had received some education were able to take their place in Canadian society with all its advantages. If the advocates of the traditional Indian way of life were to go and live, subsisting by hunting in the North-West for a year, in tribes, in the real-life material and moral conditions of the time, with a witch doctor to treat them, they would undoubtedly soon shed their illusions!

What should be remembered is that Archbishop Taché of Saint Boniface and Bishop Grandin of Saint Albert had developed a Catholic education network fifteen years before the one set up by the government in 1870. When the Grey Nuns arrived in the West, they were able to open schools a short distance from the missions, i.e. not far from the parents’ homes. Children from 6 to 14 years of age were accepted. The teaching was not academic, but adapted to their future way of life, conserving in particular their mother tongue. These missionary bishops did indeed want to tear these children away from pagan life, its ferocity and its witchcraft, but they did not tear them away from their parents. On the contrary, they wanted to make apostles of them. After their schooling and while waiting for their marriage, Bishop Grandin advocated their paid employment near the mission.

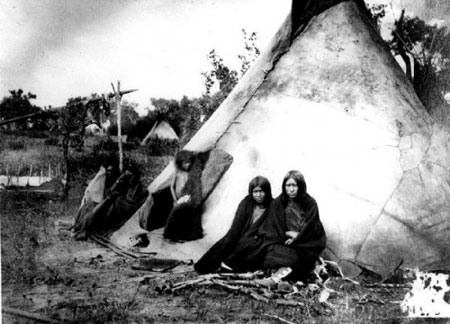

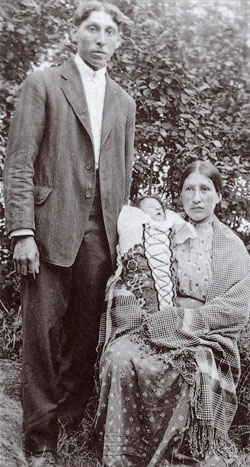

In a report, Bishop Grandin explained his charitable intentions which earned him the affection and attachment of the Indians. “For more than 25 years that I have been working to evangelise the savages of the Northwest, I have been able to acquire the certainty that the best means, I would dare say the only one, for doing real and lasting good among them, is to take the little children and make them one’s own. They are made to forget the customs and habits of their ancestors to make a nomadic life impossible for them and to turn them into civilised men. To attain this, we had to overcome many difficulties. Even the inhabitants of the country laughed at my efforts in the past and told me: give a savage as careful an education as you like, he will always be a savage. Based on facts and 27 years of experience, I can assure you that it is the lack of education that makes the savage.” His results were astonishing, as the documents of the time testify and, in particular, the photographs of his Christian Indian families radiating virtue.

Bishop Grandin would have liked to see the foundation of such schools on the reserves: “Their example would have a beneficial influence on the other children and on the adults themselves. Once married, they would become as many farming instructors in their nation and within a hundred years the savages would have ceased to exist as savages, but they would live as civilised people, they would be useful to the country and could be part of society. Limited to our own strength, by our unbounded devotion and self-sacrifice, we shall, as we have done up to the present time, procure the advantages of civilisation for only a few subjects, but this will not save the savages in general. In a hundred years, perhaps, there will be few of them left, they will not be transformed into civilised men; physical and moral miseries will have killed them and made them disappear, but, in the meantime, they will not be without much inconvenience to the whites of the country, and will be a much heavier burden on the Government than if they would help us to support and found the settlements I am asking it for.”

Not only did Macdonald refuse to accept his request, but he also withdrew his subsidies to Catholic schools in the missions unless the bishop agreed that they should be run by laymen! Thus his demands were in line with those of the anticlerical government of the French Republic against teaching congregations!

Bishop Taché and Bishop Grandin were not discouraged. To finance their establishments, they wanted to obtain resources abroad, and particularly in France, on the model of the aid to the Schools of the Orient. Despite Leo XIII’s consent, the Propagation of the Faith objected: it feared that its income would be reduced.

Bishop Grandin was tenacious and resigned himself to appealing only to Catholics in Quebec and the Maritimes, but it was Cardinal Taschereau of Quebec who stood in his way. The Bishop of Saint-Albert wrote to Archbishop Taché: “He told me in honest terms: ‘I do my business without you, do yours without me.’ An annual collection was nevertheless obtained by Bishop Laflèche and Bishop Duhamel, but no further collections were made after their deaths.

As a good Calvinist, Macdonald wanted the extermination of these peoples; the holy Catholic bishop wanted their progress, to do them good and to procure Heaven for them. The former despised them, the latter loved them. One must be totally blind or insincere, to claim, a century and a half later, that it would have been ideal to keep these peoples in the state they were, and to put our political leaders and the Church on equal terms in reprobation.

Moreover, if the Natives of that time were so docile to their missionaries, to the point of renouncing violence, except on rare occasions, it was because they knew from experience that the Catholic priest, the nun who cared for them and taught their children only wanted to do good to them.

Father Lacombe

We should mention here the admirable figure of Father Lacombe, one of our greatest Oblate missionaries. He was the one who persuaded the Indians to accept the demands of the Dominion, having understood that it would be merciless and would not hesitate to exterminate the rebels.

This peace-making role was accompanied by ardent pleas from the bishops to the government. Bishop Grandin stayed in Ottawa for weeks to get justice from “Old Tomorrow,” the nickname given to Macdonald because he always promised what was asked of him, but always put off fulfilling his promise until later on. As Bishop Grandin wrote to Father Lacombe: “It seems that in principle an injustice committed by a government employee becomes justice. It was only several years afterwards that I was able to obtain justice, and only by threatening to have recourse to publicity; this argument was for me, on several occasions, the best one with all the parties.” Then he recommended to his missionary to have no qualms about using it.

Once again, we realise that the tragedy of these valiant bishops of the North-West was to have Cardinal Taschereau in the primate see of Quebec, he who did not want to break the alliance of the Catholics with the politicians. The good understanding between well-bred people was well worth the sacrifice of the western savages who were none of his business.

The chapters of Bishop Grandin's biography concerning this decade of the 1880s should be read: their titles alone are enough to suggest their content: “The Dregs of the Chalice,” “The Assault on the Powerful,” “The Slaughtered Flock.”

Let us not forget that, as early as 1870s, these Oblates had understood that the massive arrival of immigrants, mostly Protestants, and the founding of Masonic lodges would not only condemn the Natives to famine, but also dispossess themselves of the fruits of half a century of heroic missionary action.

A century and a half later, the anticlericals, the godless and Freemasonry are still waging the same battle against the Church. Faced with the disastrous consequences of their racist, inhuman policies, instead of denouncing the persons truly responsible for them and dissociating themselves from them, today’s Conservative and Liberal politicians know nothing better than to organise appeals for ceremonies of forgiveness that will earn them a few extra votes without changing anything in the current sad state of Canada's Aboriginals. They, however, use the occasion to smear the work of those who did everything to oppose the genocide programmed by their fathers! Truly, deceit reigns supreme in our societies!

The Catholic Renaissance no.236, April 2016