SAINT CHARLES DE FOUCAULD

14. The Great War

THE SAHARA STAYS CALM.

WAR was declared on the 2nd August 1914. On the 25th November, Father de Foucauld wrote to the future General Dinaux:

«It was not until the 3rd September that news of the war reached us here. I spoke about it with the natives who had learned the news at Fort-Motylinski, but regarded it as a matter of no importance. They don’t give it a thought and have no idea of what France is going through. So, they remain profoundly calm and are concerned only for their material interests.» (Amitiés Sahariennes, vol. II p. 458)

On the 15th September, he wrote to Mother Saint-Michel:

«We have just learned the news of the war... You know how much my prayers are at the front. How many souls will suddenly appear before God, and so ill prepared... Europe will emerge from this war either independent or subject to the Germans; France may emerge either exalted or profoundly humiliated for centuries to come. May God protect France; may He have pity on so many souls; may He cause good to emerge from so great an evil.»

On the same day, he wrote to Marie de Bondy:

«You know how much it costs me to be so far away from our soldiers and from the front. But it is clearly my duty to stay here in order to keep the population in a state of calm. I shall not leave Tamanrasset until peace is declared. Everything is calm here: the Touaregs know nothing of Germany, not even the name, and they have not the slightest idea of European affairs. The calm will continue unless there are serious uprisings in southern Algeria or northern Sudan, or unless there is serious agitation from the marabouts in Sudan or Tripolitania. So far, nothing of that sort has appeared, and the Touaregs are totally unaware of the grave situation we are in. Do not worry, therefore, about me. I do not think I risk any danger here, as long as there are no uprisings in Algeria or in the Sudan.»

He remains at his post, therefore, working for peace by his very presence, but inwardly he is eating his heart out at the thought of those engaged in battle over in Europe. It takes more than a month for the news to reach him.

On the 12th December 1914, he writes to the Trappist, Brother Augustine:

«My nearest relations, nephews, and nephews according to the use of that term in Brittany, who are under fire, are all right so far. General Laperrine was also faring well on the 16th October. Among my friends and more distant relations, more than one has been killed - thirteen so far. Pray for the living and the dead. May God keep France and the French and all their subjects and allies! May He bring good for souls out of this trial!

«You know that I would love to be close to our soldiers, but I think I can be of more use here, helping to maintain the state of calm. Our Touaregs from the Sahara, moreover, are perfectly calm, wholly occupied with their material interests. Our people here are quite indifferent to the fact that Turkey has entered the war, and it makes no difference to them and to the prevailing calm. They are not likely to relinquish their calm unless violently stirred up by outside agitation: but again, that would be very difficult.» (“ Letters to my Trappist brothers ”, Cette chère dernière place, Paris, 1991, p. 392)

Father de Foucauld gave a reassuring explanation of the conflict to the Touaregs so that they might understand without being disturbed. There was not a word about Turkey, which would be capable of mobilising Islam and creating a disturbance. It was as though Turkey did not exist! The Sahara thus entered the war in peace. Fortunately, the Sahara was much more concerned with the raid in which Moussa was nearly captured. After a miraculous escape, Moussa pursued his assailants from October 1914 to January 1916, which was all time gained! Father de Foucauld followed these events very closely and kept the colonial officers informed, as we read in his letters to Commandant Duclos (Amitiés sahariennes, vol. I). He himself changed nothing of his routine. He wrote to General Meynier on the 30th March 1915:

«I am delighted with your tour around the Ahaggar, not only for myself, but because it will be particularly useful this year when, as a result of events in Europe, it is a good idea for the French authorities to be seen as much as, or rather more than, usual: it gives the natives the impression that everything back in France is following its normal course, and that even though there are wars in Europe, they present no danger to France, whose strength is unshakable. Such is the impression I do my best to convey.» (Amitiés sahariennes, vol. II, p. 411)

He himself remained totally isolated in the midst of a population vegetating in extreme poverty. It had not rained for five years, and so there were no crops. And anything that did manage to grow was devoured by locusts, which had overrun the region for a year. An epidemic of fever broke out in which people, goats and camels died. In the midst of so much poverty, theft and demands for money all increased.

The Father fell ill. With the deprivations he endured, his body was worn out. Doctor Vermale, who was called to his bed on the 6th January 1915, diagnosed advanced scurvy. After visiting a sick person himself, the Father was seen accompanied by a little girl for the illness had affected his eyes.

Six months later, he wrote to Marie de Bondy:

«I cannot say that I wish for death; at other times I would have looked forward to it. Now that I can see all the good that needs to be done and all the souls without a pastor, I would very much like to do some good and to work a little for the salvation of these poor souls: but the good God loves them more than I do, and he has no need of me. May His will be done...» (20 July 1914)

Our Lord had reserved another kind of death for the hermit of the Hoggar. For the time being, he was put back on his feet and recovered through the care of the doctor. In the time left after receiving his many visitors, he got on with his language work: «It seems strange to me, in these very grave times, to be spending my days copying out pages of verse!» he wrote to Laperrine in August 1915. Yet, by the 10th June, he was up to the letter Z of his dictionary: 2028 pages copied and re-copied, which are still there to be admired in exhibitions devoted to Father de Foucauld.

He also got down to the task of teaching the women and the girls how to knit and crochet, and he asked Marie de Bondy to send him the necessary materials:

«All these things are spiritually useful because everything stands together: these people can only be made to quit Islam if they are given instruction, thus opening their minds and giving them some idea of and the desire for, firstly a material life superior to their own and then for a superior intellectual life; for the moment, they have no concept of this and consequently no desire for instruction. They find it easier to understand the idea of perfecting their material life, but if they make progress in this, they will acquire the habit of work and will settle down. Then gradually their minds will open and they will be led to travel; the rest will follow little by little. » (16 April 1915)

“ ANGOR PATRIÆ ”.

From the very first day of hostilities, the Father was seized with anguish for his country and very attentively and closely followed events at the front. He has left a great many letters, which open his soul to us.

Even before the outbreak of war, he was concerned about the decadence of France, in terms that are as brutally topical as they were then. He expresses his concern in one of his first letters to Joseph Hours, dated 24 July 1914, one week before the declaration of war. He sounds the alarm:

«May God keep France! How is it that France has reached the point at which she now finds herself? Great harm has been done to our faith by the lowering of philosophical and religious studies. Young men, even though piously brought up, are far from being educated in philosophy and when they reach an age when objections arise from their own minds or from their reading, they are defenceless. The age limit in schools means that studies have to be rushed, and anything not on the programme is omitted, even for Christians. Our developing material well-being has entailed a widespread pursuit of futilities and of research opposed to Christian simplicity and moderation and contrary to the good arising from the spirit of poverty and mortification. It has dug an even deeper rift between proprietors and workers and has diminished Christian fraternity and charity. It has led to the more cultivated minds spending far too much of their time in the quest for profit and the workers spending too much of their time acquiring their daily bread. There are other causes too, but increasing ignorance and the growing need for material goods are the two main causes. There has to be a reaction.» (Letter to Joseph Hours, Cahiers Charles de Foucauld, n° 16, 1949, p. 99)

This war was something that could be seen coming long in advance. There was such a difference between the mentality prevailing in France and the discipline, militarism and aggressive mentality which had been forged in Germany by Bismark... France’s defeat in 1870 had simply reinforced Germany’s self-confidence and its impetus for overall domination.

Furthermore, France had been weakened and divided as a result of the Dreyfuss affair, and her intelligence service beheaded before an increasingly aggressive Germany, as had been demonstrated by the Kaiser’s visit to Tangiers... All French nationals were aware of the threat weighing on their country. Action Française had organised street campaigns and with great difficulty had succeeded in having military service increased to three years, a decision that was implemented only on the eve of the war, but that was to spare us defeat.

In addition, France was infested with spies, as Léon Daudet had proved in his “ l’Avant-Guerre ”. Socialists like Jean-Jaurès and Christian Democrats like Marc Sangnier joined forces to declare that, whatever happened, there would be no war because the German socialist workers would revolt against the Kaiser rather than go to war against their fellow workers in France. During his travels, Father Foucauld had been much disquieted by this.

From the day when war was declared, he threw himself into prayer and formulated all sorts of heroic vows, which are ardently expressed in a letter he wrote to Joseph Hours dated 21 October :

«May Jesus protect you and all yours in the midst of this storm through which France and Europe are now passing. May He protect France and bring her out of this trial better, wiser and more Christian. May He guard our allies and our subjects of all religions - all those who are fighting for us and who are mingling their blood with ours. May He have pity on the many souls who appear before Him daily. After this storm, may He cause better days to shine on this world when souls can go straight to God and may He keep them far from the vanities of this world. Hallowed be His Name! May His Will be done! May His Kingdom come! » (ibid., p. 100)

He wrote to Laperrine every day. On this same 21 October 1914, he confided in him as follows: «The way the war is going shows how necessary it was; it shows how great the power of Germany was and that it was time to break its yoke before it grew even more fearful; it shows the kind of barbarians to which Europe was half enslaved and near to becoming wholly so, and how necessary it was to deprive those people of power once and for all, for they make bad use of power and always in a way that is immoral and dangerous for others.» (Bazin. ed. 1921, p. 430)

A few months later, he wrote to his friend General Mazel, with whom he had been in the same year at Saint-Cyr:

«Never until now have I felt the happiness of being French. We both know that there are many miseries in France, but in this present war, she is defending the world and future generation against the moral barbarity of Germany. For the first time, I understand the Crusades: this present war, like the Crusades, will result in preventing our descendants from becoming barbarians. That is a benefit which cannot be bought too dearly.» (Castillon, p. 474)

And further on: «It is necessary to destroy German militarism and to extirpate the possibility of their starting again... There can only be lasting peace at the cost of their total defeat.»

To Gabriel Tourdes, he wrote on the 15th July 1915:

«May we soon be rejoicing in complete victory, re-entering our Alsace become French again, and see a solid peace established sheltering the world from the invasion of German barbarity for a long time to come... » (Letters to a school friend, p. 183)

There we have the ardent thoughts of a saint faced with an appalling cataclysm. And here we have the supernatural hope of seeing good come of all this for the good of souls. He writes again to Joseph Hours:

«Like you, I hope that out of this great evil, which is the war, there will emerge a great good for souls. Good for France, where this vision of death will inspire grave thoughts, where the fulfilment of one’s duty will lift souls up, will purify them, and bring them closer to Him Who is Goodness itself, will make them more apt to perceive the Truth and give them more strength to live in conformity with it. Good for our allies who, in becoming closer to us, become closer to Catholicism, and whose souls, like ours, are purified through sacrifice; good for our infidel subjects, multitudes of whom are fighting on our soil, getting to know us and growing closer to us, and whose loyal devotion and daily presence inspire the French to be more concerned for them than in the past, and will stir the Christians of France, I hope, to work for their conversion much more than they have in the past.» (Cahiers Charles de Foucauld, no 16, p. 101)

A little further on, he quotes Saint Teresa of Avila, as though to exhort himself as well as his correspondent, to stay calm, whilst millions of Frenchmen are on the battlefields and, among them, all his friends with whom he was together at Saint-Cyr and Saumur:

«Let us take for our rule Saint Teresa’s motto: “Let nothing disturb you, let nothing frighten you, everything passes. God does not change. Patience obtains everything. When we have God, we lack nothing: God alone suffices!” Let us work with all our strength, for God, for France; let us offer ourselves as victims. Let us pray and work at what is useful.»

On 20 November, he wrote to Henry de Castries:

«The more we go on, the more fronts that are opened, so the battle develops in this war as has never before been seen in this world. We would have wanted the war to be short, but I believe, despite what certain neutral countries think, that, without her governors seeking it, the eldest daughter of the Church continues to fulfil her providential mission, with the help of God who has so visibly protected her from the first day of this war; and for the fulfilment of this mission at the present hour, that is to say, for the salvation of Christian civilisation, of Christian morality, and the freedom of the Church and the freedom of peoples, God wants a long war: only a long war can weaken the once strong Germany, to the point of begging for mercy. The length of the war is also for the allied peoples a punishment and a lesson they stood in need of. Let us hope that they will emerge the better for it. Caritas omnia sperat.

«May the good God keep you, my very dear friend; may He protect France; may He give us the full victory!

«You know that, with all my heart, I am yours affectionately and devotedly in the Heart of Jesus.

«Charles de Foucauld.»

(Letters to Henry de Castries, p. 215)

His reactions are all of supernatural Hope. He is certain that this war is a benefit for souls! So many French anticlericals will regain their faith in the trenches, and through the ministry of the chaplains, they will die like heroes and saints.

But there are so many who die in action that Father de Foucauld asks himself whether his place is not on the battlefield. On the 2nd August 1915, he wrote to General Laperrine:

«In case the laws of the Church allow me to enlist, would I do better to join up? - If yes, how do I go about getting enlisted and sent to the front (for it is better to stay here than to be in a depot or in an office) ?... Between the tiny unit that I am and zero there is very little difference, but there are times when everyone should offer himself... Answer me without delay.» (Bazin, p. 433)

Laperrine wrote and told him to stay in the Hoggar: the presence of Brother Charles de Jesus is necessary to keep the population calm, for nearly all the officers of the southern Sahara have been recalled to France. He will remain at his post, therefore, supporting those on the battlefield with his letters.

Laperrine wrote and told him to stay in the Hoggar: the presence of Brother Charles de Jesus is necessary to keep the population calm, for nearly all the officers of the southern Sahara have been recalled to France. He will remain at his post, therefore, supporting those on the battlefield with his letters.

He writes to Brother Augustine, a Trappist from the Abbey of Our Lady of the Snows:

«I weep with you over good Brother Ernest. The good God has received him on high among the martyrs of charity.

«This war is not like other wars. Those who die in it give their lives to spare their brothers and sisters not only a degrading subjection, but all the cruelty, violence and abuse of the worst barbarians. They are truly martyrs of the love of their neighbour.

«Thank you for the news you give me of all the dear Fathers and Brothers on active service; you know how much I pray for them, asking the good God to keep them and to do them much good; they are missionaries among our soldiers, not by their words maybe, but by their example, virtue and goodness, which is worth more. The good God is bringing good out of evil. The effect of laws against religion is to spread religion; a war which covers the world with blood and ruins brings many souls back to God, and for Europe it is a necessary, and I hope, fruitful lesson.

«My humble and most affectionate regards to Father Abbot. Commend me, as well as my Touaregs and my nearest and dearest at the front, to the prayers of Our Lady of the Snows. To all, my faithful prayer and my heart. May God keep you and may He protect France!

«I embrace you with all my heart as I love you in the Heart of Jesus. Charles de Foucauld.»

(Cette chère dernière place, p. 398)

At the same time, he is following events very closely:

«How greatly this war fills me with gratitude and admiration for Belgium and her King! How it tightens the bonds between the French and certain peoples, with the Belgians first of all, with whom we are united not only by kinship of race but now by such gratitude! With the English and then the Russians. May God bring the good of souls out of this trial. There are many of our subjects here, and of our Muslims from France, shedding their blood with us and for us. Let us pray for them. Let us do what is useful for their souls...»

He learns of the proud declaration made by Cardinal Mercier, calling on the Belgians to redouble their patriotism, and he is full of admiration.

But this war touches him very directly, since in 1893, when he was at the Trappist monastery of Akbès, he had been a powerless onlooker whilst 160,000 Christian Armenians were massacred under the most barbaric conditions, the Turks showing themselves to be of the most outrageous ferocity. Now the Turks were Germany’s allies. Father de Foucauld wrote to Laperrine on the 6th December 1915:

«I hope that our affairs are going well on all our fronts, the number of which is increasing. What barbarity the Armenian massacres displayed: people sold into slavery in bulk, women selected for the harems! If Turkey is allowed to subsist as a State after that, it will be a shameful thing for the allies. It is already a matter of shame for the Americans and other neutrals, who could have repressed these horrors, but who folded their arms. I had thought that, on entering the religious life, I would especially have to counsel meekness and humility; with time, however, I see that what is more often lacking are pride and dignity! There are two things I ardently desire: that Turkey should cease to be a State, that she should be divided up among the European states, and that Germany should beg for mercy, should lose her unity, should no longer have the Hohenzollerns for princes, and should be made incapable of doing harm. Secondarily, I desire that we have no part of Turkey, the Holy Land or anywhere else. We have enough with our own vast colonial empire; let us work for its progress and prosperity, and administer it well, but not increase it.»

There is wisdom, as opposed to the French who thought only of expansion and of robbing still more territories from this one and the other for the aggrandisement of their empire.

THE PRESENT WAR IS A TRUE CRUSADE.

It is then that there gradually took shape in his mind an idea that is going to become predominant. On the 22nd February 1915, he wrote to Commandant Duclos, who was not exactly a fervent Christian:

«Those nearest to me who are under fire have so far been spared; I hope the same is true for your men too...

Out of my more distant relations and very dear friends, many of them are already asleep after having given their blood in this crusade; you may have known one of them, Captain Jacques d’Ivry, who commanded a battalion of Moroccan infantrymen, killed gloriously on the 5th September, - a very dear friend.

«This war is indeed a crusade, a crusade for the freedom of a threatened world, for civilisation, for the ideas of law and justice, for the freedom of France and of all other countries, for all liberties, none of which would exist if German tyranny, German injustice and German barbarism were to prevail.

«I pray God to preserve you in this war, to keep you in the affection of your family, my affection too, and that of France and French Africa. Victory will be the prelude to a new era of prosperity for France and of development for the colonies, especially for North Africa, which has taken such a great and brilliant part in the war and which is an extension of France: you will, I hope, be among those who work for this development and for the progress that will be made.

«Have you read Cardinal Mercier’s pastoral letter? One could not find a better summary of Catholic doctrine on patriotism and on the well founded hope that Heaven is open to those who die for their country, in the most noble exercise of charity, that of giving their life for their fellow countrymen.

«What a joy it will be to see each other again and to embrace after the victory! In the meanwhile, I embrace you with all my heart, as I love you in the Heart of Jesus.

«Charles de Foucauld.»

(Amitiés sahariennes, vol. I, p. 160)

And on the 9th January 1916:

«I had never really understood the Crusades. Now I understand them; God will once more save the world through the eldest daughter of His Church.» (ibid., p. 198)

Throwing into the scales the weight of his supernatural faith, he never ceases to impress upon his correspondents the thought that this war is not like any other war between two, three or even twenty countries. This is really a Crusade where the salvation of the world is at stake. And France is God’s instrument. He wrote to Marie de Bondy on the 11th January 1916: «The present war enables me to understand the Crusades. Especially that of the Albigensians. Now I understand. It was Christian civilisation, the independence of nations, the traditions of honour and of virtue, the freedom of the Church, often the life and honour of persons that were at stake, as they are now. I am fully confident that God will keep France and that through her who remains, despite all, the eldest daughter of the Church, He will save the principles of justice and morality, the freedom of the Church and the independence of peoples. I also hope that the peace will give rise to a better France, more virtuous and more Christian, to peoples more fraternally united together, and also to more zeal for moral progress, sound administration and the salvation of the souls of the natives in our colonies. May the good God protect France and make much good come out of so many evils.» (Lettres, p. 240-241)

We can see that the Father was expecting a renaissance of Catholic civilisation to result from this gory trial, on condition that «our soldiers completed the victory over the enemy outside by curing certain evils within», as he will write to Fitz-James.

He prays to Our Lord God, «That He may protect us to the end, that He will make a better and greater France to emerge from this storm, a Christian and more Catholic Europe. Several great Catholic movements have already begun. There have been very many consecrations to the Sacred Heart on the part of individuals, families, associations and military units, and there is the vow to make a pilgrimage to Lourdes after the victory. The war has also helped bring together France, the eldest daughter of the Church and the greatest Catholic nation, on the one hand, and the protestant and schismatic peoples of England, Russia and Serbia, on the other, which in turn will bring the latter closer to the one Shepherd and the one Fold.»

To compare these hopes and prayers with the reality of the post-war years is to understand how strong was the devil’s work: the French, who had wrought marvels of heroism, will not be capable of going the whole way with the war; they were prematurely stopped by their Government, when « three or four days of battle would have condemned the German armies to capitulate in the open country. It is to escape this disaster that Germany signed the armistice» (Poincaré, 1st December 1919).

Far from drawing closer to Catholic France, the Allies will begin, in the thick of the war, to plot the humiliation of France and Austria, Catholic nations, in order to safeguard... Germany!

THE FRANCE OF THE SAINTS AND OF THE KINGS SHALL NOT PERISH

«We must pray for France, our country, more then ever, that she may emerge from this storm, in which all Christendom is finding itself more Christian, wiser and better, with a more beneficent action in the world; at any rate, her Christian majority is more faithful than any other to the Holy See, more apostolic than any other through her missions, through her men and women religious established in distant places. The devotion to the Sacred Heart, which has its home in France, the apparitions and miracles of Lourdes for which God chose France, are very comforting proofs of the Christian spirit that continues to reign in France, despite the appearances of a government that denies religion whilst sullying its influence in many things.» (Letter to the Poor Clares of Nazareth, refugees in Malta, at the beginning of 1915.)

«The present war is a true Crusade, in which France, ever the Church’s eldest daughter, is fulfilling her providential mission, protecting Europe and the world against the invasion of German paganism. What would become of future generations if the Germans were to impose their material and moral domination, and if their antichristian principles were to reign in souls and over Europe? And France, despite all appearances, remains the France of Charlemagne, of Saint Louis and of Saint Joan of Arc. The old soul of the nation is still vibrant in our generation: the saints of France are still praying for her. God’s gifts are given without regret, and the people of Saint Rémi and of Clovis remains Christ’s people... In choosing France for the cradle of devotion to the Sacred Heart and for the apparitions of Lourdes, Our Lord has indeed shown that He keeps France in her rank as first-born... These martyrs of charity, who have given their life to protect their brothers and sisters of France from the cruelties and horrors of the German invasion, are helping our armies with their prayers and from Heaven they are fighting for us...

«With you and my sisters, I shall pray this day for France and the Allies, even more than I do daily, asking God for complete victory on every front, and a glorious peace that will repair the past and guarantee the future in as far as possible, asking Him that France and her Allies may enjoy a new era of Christian renaissance, of holiness, of true greatness and of beneficent influence in the world. (Letter to Mother Saint-Michel, 28 November 1916)

But in the end, because this is a “holy war”, the soldiers will not have fought in vain:

«How happy we are to be born French, to be in the camp of the right and the just, in the camp that is fighting for Christian morality to remain the law of the world, and to become even more so, for the liberty of the Church and the independence of peoples. It is the whole heritage of Christianity that is being defended by France and the allies. “Gesta Dei per Francos”. Through the grace of the Church’s Divine Spouse and of the Divine Spouse of faithful souls, the eldest daughter of the Church is pursuing the fulfilment of her providential mission in the world. Trust and hope.»

That is why Brother Charles de Jesus crowns all those soldiers who have fallen on the field of honour with the title of «martyrs of charity», and more and more they are to be found in the ranks of his friends and close relatives. He writes to Madame Bricogne, who has just lost her husband:

« I pray faithfully for him, even though I am certain that he is enjoying the eternal light, as a martyr of charity, having loved his brothers of France with the greatest love, that of laying down his life for them. Not only has he sacrificed himself to save French men and women from the German invasion, but it was in a true Crusade against a new paganism that he fought to the death. Our brothers who fall at the front belong to these martyrs of charity.

« This war is such that we are fighting as much for the whole world and for civilisation, as for ourselves... Hence, this is truly a holy war. And that makes one understand why the name of holy war has been given to other wars.»

He is extremely faithful in writing to the combatants: one guesses that this is his way of serving. The combatants are no less regular in replying to him, like General Gourand, who having lost his right arm in action, wrote to him with his left hand.

In October 1916, all his thoughts turn to appealing to the Sacred Heart and to the Immaculate Heart of Mary:

«I am happy about the vow made by the French bishops to Our Lady of Lourdes and also with the way individuals, families, societies and military units are consecrating themselves to the Sacred Heart. We are thus turning towards our true protectors: Our Lord who has chosen France for the revelation of the devotion to His Heart, and the Blessed Virgin who has chosen France for Her appearance at Lourdes.» (to Marie de Bondy, 30 October 1916, Lettres, p. 250) He himself promised to go on pilgrimage to Lourdes after the victory.

SENOUSSIST INSURRECTION IN TRIPOLITANIA.

In the meanwhile, he mounts guard in the Sahara. He gives information and advice to the few officers who are watching over this vast territory as big as France, with greatly reduced troops.

On the 1st September 1916, he complains to Commandant Duclos:

«The Ahaggar has been abandoned since the 1st August 1914; it is dangerous to leave it like this. I understand the difficulties. But I also see the dangers of an abnormal situation being prolonged.» (Amitiés sahariennes, vol. I, p. 255)

From the beginning of the year 1915, rebel troops infiltrate from Tripolitania, an Italian possession since 1912 (present day Libya). In the south, the Fezzan in the desert is in the hands of the Senoussists, the worst enemies of France, whose religious fanaticism conceals an implacable will for expansion and domination. Three hundred men are sent as reinforcements, to provide a guard to the east, two thousand kilometres from the frontier! To the west, southern Morocco is still very far from being pacified. The Adrar is heavily raided, with attacks on Moussa’s tribes in the Hoggar, which are all the more daring, the less resistance they meet from the French. Fortunately, Moussa remains faithful to France.

In September, the Libyans revolt against the Italians and attempt to cross the frontier of southern Tunisia. They are flanked by the Germans...

Two of our posts undergo repeated assaults and defend themselves outnumbered by one hundred, by thirty to three thousand. In 1916, the Moroccans increase their attacks in the Adrar, and Moussa pursues the raiders in an attempt to crush them.

At the Tripolitania frontier there is fighting. On the 6th March, Djanet is assaulted by Ahmoud with a thousand Senoussists.

The Fort is defended by Sergeant Lapierre, commanding fifty men. For a post of such importance! The Fort has no well. The Senoussists know this, so they wait until the defenders, dying of thirst, emerge for fresh supplies of water, and then the post will be taken with no great difficulty.

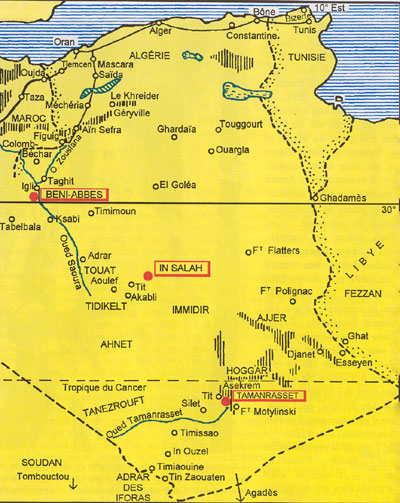

Father de Foucauld learns this and weighs up the danger: of the three main posts providing defence at 2,500 kilometres from the frontier, there only remains Fort-Polignac and Fort-Flatters to the north (see the map, CRC no 294, English edition, March 1997, p. 20).

The frontier is open to invasion from the south. The Hoggar is without military defence as far asTamanrasset, defended by Fort-Motylinski, established 50 kilometres to the north.

On the 10th April, he wrote to Commandant Meynier:

«What will the enemy do after the capture of Djanet? Will he act as though satisfied for the time being? Will he attack Polignac, Fort-Flatters, Motylinski, simultaneously or successively? In any case, Motylinski must hold itself in readiness for anything. Constant has received from Captain Duclos orders to put Motylinski into a state of defence, without delay. But, Motylinski is indefensible against an enemy with cannons; even against an enemy without cannons but who are numerous, defence is almost impossible because of the water situation.» (Amitiés sahariennes, vol. II, p. 426-428)

Having advised that «an impregnable place supplied with water» be set up in the mountains of the Ahaggar, to which the garrison could retreat, Brother Charles de Jesus adds:

«For myself, I am staying here, for I do not want to appear to be afraid, and am anxious rather to appear confident and smiling, also to counsel Ouksem and Litni and to give Constant [the second-lieutenant and head of Fort-Motylinski] the benefit of the information and of the clues I pick up here. In case of attack, I shall join Constant without delay. If I think it useful, I shall make brief visits to Constant from time to time.»

Father de Foucauld is a strategist! In his book Charles de Foucauld, Français d’Afrique, Pierre Nord shows that the hermit knew what was going on six hundred kilometres to the north, five hundred kilometres to the east, and what was going to happen six hundred kilometres to the west: one wonders how! He is at the centre of all the information with which all the Touaregs provide him out of an intense sense of loyalty. He stays, therefore, at Tamanrasset, but goes all the same to Motylinski in order to encourage second lieutenant Constant. He writes to Commandant Duclos:

«As I told you a few days ago, Constant, although not cut out to be an officer of native Affairs, will, I think, make a very honourable officer of troops. He is much the best head of post that we have had at Motylinski. He is very gentle with the natives... But it is obvious that he lacks formation.» (23 September 1915, Amitiés sahariennes, vol. I, p. 182)

A little later, and the Father has perfectly sized up his man: «He is light-minded, inclined to gossip, but I think he is honest, of good mind and good will.» (ibid., p. 197)

Then comes the revolt of the Ioulliminden, to the South, from the direction of the Agadès: these important Touareg tribes, acting on the orders of Chief Firhoun, go over to the enemy. Fortunately, Commandant Meynier recaptured Djanet after thirty hours’ fighting. It was a great victory, especially as the Senoussists were pursued, scattered, and that various favourable battles restored the garrisons’ confidence.

Moussa ag Amastane was certainly encouraged in his loyalty to France as a result of this. But Father de Foucauld is worried about him and deplores the attitude of certain officers towards him: Lieutenant de Saint-Léger shows too much confidence in Moussa whilst Lieutenant de La Roche, who commands the Southern Hoggar alone, suspects Moussa of having gone over to the enemy and treats him harshly, thereby giving him an excuse for joining the rebels. The Father confides his thoughts about all this to Commandant Duclos, in a letter dated 16 April 1915:

«When we are able to talk together here at leisure, which I hope will be soon, I shall tell you all about the misfortunes caused by the administration of the corporals or sergeants; Saint-Léger will also tell you about this. Saint-Léger’s knowledge of this whole Touareg country is admirable, and I would urge you to have orders passed through him for some time, on points you judge to be useful. It is just that I think that he shows too much confidence in Moussa. Moussa is very intelligent, energetic and courageous, as Saint-Léger knows ; on the other hand, he is a liar and crafty too, which Saint-Léger does not sufficiently realise as a result of his three years’ absence. I believe that Moussa is loyal to France because he understands, especially since his visit to France, that it is a necessity. » (Amitiés sahariennes, vol. I, p. 165)

Here we touch on the trouble with our civilised philanthropists, our Father comments. Through a sort of psychological transference, they attribute to the primitive peoples they have to deal with sentiments that are absolutely foreign to their mental world. All the progressivist theories which have lost us the world are based on ignorance and utopianism on the part of naive people who think they are dealing with people who are as naive as they are themselves. They know nothing of the psychology of primitive people who know neither A nor B, but whose struggle to preserve their lives against difficulties has forged for them powerful instincts. They are meat eaters, people who fight for life. With them, it is win or die. When we see nomads submitting to us, we think they are attached to us with their heart. Father de Foucauld, who had a heart of gold, also had a very sharp intelligence and he lived in such close contact with them that he knew their deepest motivations. We can say of him, as is written of Jesus: “He did not trust himself to them, for he knew all people” (Jn 2. 24)

This is what he said about Moussa:

«Whilst being loyal and attempting to bring his people into contact with us, in order to avoid reproaches for himself and punishments for them, he seeks to govern them without us, as though we did not exist. He surrounds himself (especially out of vanity) with marabouts who are foreign to the country, who detest us, whose influence is bad, and who are plainly awaiting the arrival, thirty years hence, of the Mahdi, who will subject all the Christians and other infidels to the Muslims, and who will establish the reign of Islam over all the earth - events that are announced as certain by all the tolbas of the country (all strangers, from Rât or from Tidikelt) and as bound to happen within thirty years... As these populations are not very religious, what the tolbas say does not give rise to any proximate danger; they only half believe it, especially the date; but it makes everybody feel that our presence here is only temporary, for a more or less long time, during which our subjects have to be patient. I am sure that that is what Moussa tells his people: be patient, be calm; be obedient towards the pagans for as long as God gives them power over us; the time is not far off when he will give us, in our turn, power over them, when he will send his Mahdi, a time which, all the wise men say, is near.

«It is only through instruction, through contact with us, through the more intelligent travelling to France, that these errors will gradually be dispelled. Our victories over the Muslims of Morocco, Tunis, Tripoli. Egypt and Turkey only serve to entrench this belief in the Mahdi’s forthcoming appearance, for it will be preceded, so the Muslim writers say, by the greatest of calamities for Islam.» (ibid.)

Our Father concludes:

«The whole loss of our Algeria consists in this one word “ temporary ”... To these people who regarded our presence as temporary, we swore to remain with them always and to protect them. It was a false oath since our presence was, in fact, no more than “ temporary ”! That is something a Muslim will never understand, nor will the Berber ever forgive. Especially as those who were sufficiently noble, loyal and, at the same time, naive, to trust in us French who were capable of perjuring our oaths, had their throats slit... No pity: they chose the wrong side; they betrayed Islam. And we let them be slaughtered, without a protest! And then we left...

« But who then inspired these “ tolbas ”, prophesying our departure fifty years in advance ? I have no hesitation in answering : Satan. Father de Foucauld himself came up against Satan. You see how these liberals, infatuated with ecumenism, seal a union with the worst in Islam. In this great battle between Christ and Satan, we always see these false “ men of heart ” siding with the enemy each time. Father de Foucauld, on the other hand, teaches us true supernatural charity, which is to conquer, to hold on to our power over these peoples in order to allow peace to reign, to settle amongst them, gradually to assimilate them, to raise them up to us and to make them our brothers. In that way, they will come to trust us and lose faith in their “ tolbas ” and in the “ Mahdi ” to come. They will understand that we are with them for ever and they will not be afraid to convert. You see how all that comes into the Apocalypse! And when the Senoussists make their way towards Tamanrasset in order to kill the Christian marabout, they will know why : their aim is to get at the soul of French resistance and of Saharan loyalty. Because it was first and foremost a spiritual combat. But let us not run ahead... »

THE BORDJ.

Faced with the danger of the Senoussist attacks, Father de Foucauld decided to transform his hermitage into a fort so that the neighbouring peoples might find shelter. Helped by a few soldiers and by the natives, he began in April 1916 to construct this fort, sixteen metres by sixteen and five metres high. It was built with good bricks, admirably simple and of great beauty. At the centre of the Bordj, there was a well, which made it possible to sustain a siege until help came from Fort-Motylinski. The work was completed on the 23rd June, and Father Charles de Jesus installed himself there, stocking it with food supplies, medicines and rifles

Faced with the danger of the Senoussist attacks, Father de Foucauld decided to transform his hermitage into a fort so that the neighbouring peoples might find shelter. Helped by a few soldiers and by the natives, he began in April 1916 to construct this fort, sixteen metres by sixteen and five metres high. It was built with good bricks, admirably simple and of great beauty. At the centre of the Bordj, there was a well, which made it possible to sustain a siege until help came from Fort-Motylinski. The work was completed on the 23rd June, and Father Charles de Jesus installed himself there, stocking it with food supplies, medicines and rifles

«He is truly, our Father said, the soldier-monk watching over the frontiers of the Christian empire. His bordj is a bastion of Christendom, lost in the sands of the desert and facing the enemy.» Father de Foucauld writes to his former friend of Saint-Cyr, General Mazel, commander of the Vth Army :

«The corner of the Sahara from which I am writing to you is still calm. But everywhere we are on the alert because of increasing Senoussist agitation in Tripolitania; our Touaregs here are faithful, but we could be attacked by the Tripolitanians. I have transformed my hermitage into a fort; there is nothing new under the sun; seeing my battlements makes me think of the fortified convents and churches of the tenth century... I have been given six boxes of cartridges and thirty carbine rifles, which remind me of our youth... I am happy that you have our brave Laperrine under your command; I hope you will keep him for a long time. It is to him that we owe our tranquillity in the Algerian Sahara; the wisdom and vigour of his actions and the incomparable memory he left behind account for the fidelity of these peoples who are reckoned to be difficult. » (Entre-nous, September 1956, n° 15)

THE “ METHOD OF RETREAT ”.

In June 1916 our positions seemed more secure. The French troops were, however, obliged to beat a strategic retreat, for Briand would not change his policy with regard to Italy (cf. Amitiés sahariennes, vol. II, p. 275). After having retaken Djanet in May, Commandant Meynier evacuated it for want of supplies and retreated to Fort-Flatters. A little later it was Fort-Polignac that was abandoned. The official representatives of Italy and France negotiated with the rebels. Instead of putting down the revolt, they encouraged it! Father de Foucauld immediately denounced the wrong-headedness of such a strategy.

He wrote to Commandant Duclos:

«Tamanrasset, 1st September 1916

«I am entirely of your opinion on every point. On the absolute necessity of severely repressing crimes committed, desertions, acts of dissidence and going over to the enemy; on the necessity of expelling undesirables, spies and troublemakers; on the necessity of forbidding all contact between our docile subjects and insubordinate and dissident enemies, etc.; on the necessity to abstain from all negotiation with the native enemies, except in the one case where they come to ask for peace and make an act of full submission...

«To fail to repress severely is to embolden the criminals and to encourage others to follow them; it is to lose the esteem of all, the docile and the insubordinate alike, who will see in this conduct nothing but weakness, timidity and fear; it discourages the loyal who see that the faithful can expect the same, or nearly the same, treatment as the deserters, the insubordinate and the rebels...

«Not to chase out undesirables is to allow trouble to foment that may be weak to begin with but which develops and produces its full effect, and which can be very serious, reaching the proportion of a full-scale rebellion... To treat with enemy chiefs or rebels as power with power, is to exalt the enemy infinitely and to diminish oneself to the same degree... (Amitiés sahariennes, vol. I, p. 252)

On the 6th September, he wrote to Lyautey to warn him of imminent danger, allowing his anguish to show: Algiers is doing nothing to put down the rebellion!

«I am writing to you today to tell you that things are not going well along the Algerian-Tripolitanian frontier, and that unless the united action of the Senoussists, Turks and Germans is stopped, it will quickly spread to the southern Algerian and Tunisian frontiers, to the north-east of French West Africa and even to Tafilalet and to parts of southern Morocco. Having chased the Italians out of Fezzan, often without a fight, the Senoussists, who are armed and provided with money through Turkish-German action, and who have an abundance of rifles, cannons and munitions left behind by the Italians, have organised themselves and are ready, despite giving the French peaceful assurances. Lifting the mask last March, they pounced on our post of Djanet without warning and took it, after a fifteen to twenty day siege, making prisoners of the fifty men of the garrison. A column of five hundred men retook Djanet in May, after three days of fierce fighting against them. The enemy retreated in an orderly fashion and shut themselves in at Rât, where the column was forbidden to attack them (in order to spare Italian susceptibilities, we were told).

«Under the shelter of the Italian frontier, become a sure rampart for them, the Senoussists made other arrangements: they attacked the convoys and couriers to the rear of our column, threatened the posts established along its flank, made it difficult for the column to get fresh supplies, and they massed forces close to its line of retreat. In order to hold on to Djanet once retaken, our column would have needed reinforcements which it never received.

« Fearing an attack at the rear and needing all its forces to resist such an attack, our column evacuated Djanet and retreated to Tarat. A convoy bringing it supplies was taken out, so, in order not to die of hunger, the column had to withdraw even further and retreat firstly to Fort-Polignac, then to Fort-Flatters. Just as this retreat was being put into effect, the Senoussists sent an imperative summons to evacuate Djanet and Tarat: it had already been done, but the coincidence was unfortunate. It was at the beginning of August when the column retreated to Fort-Flatters... What has happened since? Was the commandant of our troops (Lieutenant-Colonel Meynier, in charge of the colonial infantry and military commandant of the Saharan oasis) supplied with the wherewithal to retake the lost ground and to hold on to everything this side of the French frontier? If yes, then things are not so bad: the Senoussists will be stopped and their action will not spread... But several letters, from Algiers among others, make me fear that they may stop somewhere else: there is talk of making our troops evacuate Fort-Polignac and Fort-Flatters. That would allow the Senoussists to reach the ports of Ouargla. To abandon In-Salah, the Touat and the Ahaggar to the Senoussists would embolden them no end; it would be a discouragement to our loyal peoples, and even incline them to join the Senoussists to prepare uprisings in French West Africa and southern Tunisia and a recrudescence in the Moroccan South-East.

«I am writing to you in haste so that if, by misfortune, Algiers had adopted or wished to adopt this method of retreat, you could make them understand the dangers involved and obtain all that is necessary to put a stop to Senoussist action on our frontier. It is very easy to stop them, for they are unable, it seems to me, to place more than a thousand men along our frontier.

«May the good God keep you, may He guard your Morocco, may He protect France and may He make the light of full victory shine!

(Gorrée, Au service du Maroc, Charles de Foucauld, p. 204)

Within a matter of weeks, Father de Foucauld will fall victim to this “ method of retreat ” (ibid., p. 207). But the call of the one-time explorer of Morocco will be heard. At the same time, Lyautey will be called to head the Ministry of War. He will appoint General Laperrine as head of the Saharan troops. The necessary action will be taken to stop the Senoussists on the frontier. Thereafter, security and order will rapidly be restored, but Father de Foucauld will no longer be there to see it...

On the 15th September, Father de Foucauld will write to Marie de Bondy: «Unfortunately, the news from the Tripolitanian border is bad... Without having suffered a setback, our troops are retreating before the Senoussists; they are no longer at the frontier, but well inside... this retreat before a few hundred rifles is deplorable. There is here (at what degree of the hierarchy I have no idea) a grave failure of command. It is clear that if we retreat without even putting up a fight, the Senoussists will advance. If we fail to change our method promptly, they will be here within a short time. I am sorry to worry you again, but I have to tell you for the sake of the dear truth.» (Lettres à Marie de Bondy, p. 247-248)

The Senoussists, therefore, recaptured the initiative. However, in October and November, Father de Foucauld increasingly wrote reassuring letters:

«It seems to me that we have nothing to fear from the Senoussists at this moment.»

He is certainly sincere. Even so, he knew, and noted in his papers, that in September a plot had been hatched to kill him, by the Harratins of Amsel, where El Madani lived... He said nothing about that and took no measures to protect himself against it (cf. Captain Depommier’s report, quoted by Bazin, p. 457).

Captain de La Roche will write in his report:

« A plot was hatched against Father de Foucauld on the 21st September. The plot was discovered; four chiefs were taken and put to death. Two others escaped.» (Bulletin des Amitiés Charles de Foucauld, n° 111, p. 10)

On the 16th November, Brother Charles de Jesus wrote to Madame de Bondy: «In these days, better than other days, it appears that life is no more than a trial and that the figure of this world is passing. May God give us all eternal life, and may He give us the grace here below to help other human beings, our brothers, to attain it...

«I am all right. Our peoples are maintaining the best attitude. There does not seem to be any proximate danger from Tripolitania at the moment. The Senoussists are still agitating and threatening, but our troops have been considerably reinforced to face them and they are probably sufficient to contain them.» (Lettres, p. 250)

And elsewhere, still on this 16th November: «How good God is to hide from us the future! What a torment life would be if it were less unknown to us!! And how good He is to make known to us so clearly this future of Heaven that will follow this earthly trial !» René Bazin, who quotes this letter (p. 449). comments on these admirable mystical thoughts:

« He who wrote these lines had no more than two weeks to live. He did not know it, but he was ready, every day, to receive death at the hand of these men for whom he had prayed so much, walked through the sand and the rocks so much, suffered from thirst and heat so much, studied so many days and nights, accepted so much solitude, and, in short, suffered so much in body and mind.» (ibid.).

CCR n° 302, october 1997