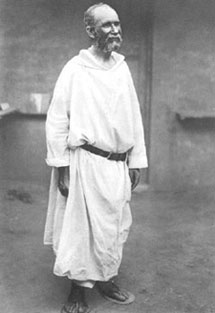

SAINT CHARLES DE FOUCAULD

15. Martyr of the Faith

BEFORE explaining the mystical significance of the death of Charles de Foucauld, our Father finds it important to establish the exact historical causes and circumstances of his death, He conducts his enquiry, examining the reports left by the military personnel: a report by Captain de La Roche, commandant of the Hoggar section, to his colonel, dated 6 December 1916; a report by Captain Depommier, area commandant of the Tidikelt and from the Hoggar to In-Salah, dated 11 September 1917; an account from Captain de La Roche to the Comtesse de Foucauld in May 1917; a note from General Laperrine of the 20th October 1927; information gathered in the Hoggar by lieutenant Proust and by second-lieutenant Béjot; and various pieces of private correspondence.

In his book, published in 1921, René Bazin quoted extracts from these testimonies. But in 1953, the question was re-opened by the Cahiers de Charles de Foucauld, with the publication of a study by lieutenant Charles Vella, a former Saharan officer, who was directly implicated in the drama, under the title: “ The real causes of the assassination of Father de Foucauld ” (8th series, no 31, p. 28-61) This document of major importance went unnoticed and needs, therefore, to be brought out into the light of day, firstly by discarding the suspicion arising from the fact that its author seems to attribute to himself responsibilities which he did not actually have in 1916. In reality, it is Michel Thiout who, in the introduction, states that Vella was «station chief at Fort-Motylinski from 1915 to 1920» (p. 28), whereas in fact he was only chief brigadier and will not be appointed adjutant until 1917, then sublieutenant on 29 December 1920. The station chief was Captain de La Roche. Lieutenant Constant, who had been in charge until July 1915, took over when La Roche had to be absent on account of lengthy operations outside the Hoggar. Father de Foucauld was in regular correspondence with Constant, as is shown by his letters of 1915 and 1916 to Commandant Duclos and General Meynier. But it is true that Vella took charge of operations as soon as La Roche and Constant were detained elsewhere, as is seen in this letter which Father de Foucauld addressed to Commandant Duclos on the 1st September 1916:

«At the beginning of April we received an unusual warning. Rumours that were contradictory in detail but in agreement over certain points, announced both the evacuation of Djanet by our troops and their retreat to Polignac and at the same time the march of the Senoussiste harka on the Ahaggar; Constant was at the sit works of the automobile track; Vella, who commanded at Motylinski in his absence, immediately prepared for defence: he sent out patrols, positioned sentinels, put the bordj on the defensive, etc.» (Amitiés sahariennes, vol. I, p. 255)

We can trust Vella’s testimony; Father de Foucauld judged him to be «an honest boy» (ibid., p. 199). Assigned to In-Salah until 1922, then to El-Oued, he continued the “civilizing rounds”, dear to Laperrine, « In the course of my rounds with the people of the Hoggar and their Aménokal Moussa ag Amastane, in both West Africa and in Ajjer, he will write, I was able to ascertain how our Saharan tribes really felt towards Father de Foucauld. With the return of peace, I was kept on as Resident Officer until 1923, which gave me every opportunity to attempt to re-establish what I believe to be the truth about both the causes of the tragedy of Tamanrasset and those directly responsible. Today, I consider it my duty to publish these facts.»

THE TOUAREGS: CONVERSION POSSIBLE.

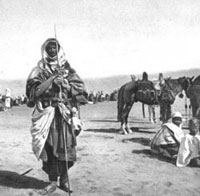

Charles Vella begins by painting as complete a picture as possible of the Sahara at that time. Concerning the religion of the Touaregs, he rightly observes: « Although theoretically Muslim, the Targui is not in fact subject to any religion. Speaking very little Arabic, often none at all, and being totally ignorant of its writing, he cannot be imbued with verses of the Koran. He believes, with no fanaticism, in God whom he calls “Massina”, but in his obscurantism implores this God only intuitively.

« The Touaregs are certainly not Arabs; ethnically, they are Berbers. But for my part, I see no racial affinity between these men and the Berbers of other regions, nor any other kind of similarity, apart from their Tamacheque idiom which is related to the Kouchite language of the Numidians from whom the Berbers are descended.

« In every respect, the Touaregs are quite unlike the various Berber tribes I have come to know: Berbers of Kabylie, of the Drâa or Moroccan Tafilalet, the Troglodyte Berbers of Southern Tunisia and of Tripolitania, who are all alike in their customs and morals, and especially in the fanatical practice of the Muslim religion.»

Suggesting that the Touareg tribes might have links « with the various races who successively invaded Egypt at different periods of Antiquity», he concluded in this fascinating hypothesis:

« It is also possible that these mysterious veiled people owe their feudal origin, their ancient weapons and their cruciform art, to Christian contacts in Egypt or in the vicinity of Egypt, perhaps even with the XIIIth century Crusaders who, in their turn, occupied this attractive country for six years.»

In any case: « This detour concerning the origins of the Touaregs shows that the conversion, or rather the attachment of these undecided souls, which was envisaged by Father de Foucauld in 1905, was not utopian.» Let us say that it was the project of a saint who did not live on illusions but on supernatural hope:

«First of all, our Father explains, we must realise to what extent Brother Charles de Jésus lived among “Apaches”, as he called them (cf. letter to Colonel Sigonney of the 3rd June 1910, Amitiés sahariennes, vol. II, p. 204), and among Muslims, some of whom were indifferent and others fanatical. At Tamanrasset. Father de Foucauld had first of all supported and favoured the serf tribe of the Dag Rali, the imrads, against the “nobles” who regarded themselves as their masters, rapacious bandits and plunderers whom he recommended should be firmly brought under the common law.»

Vella continues: «In 1913, the Father travelled to France, taking with him the young Ouksem ag Chikkat, nephew of Ouksem ag Ourar, chief of the Dag Rali tribe (cf. photo reproduced on page 26 of the CRC n° 296, English edition, May 1997). Charles de Foucauld was counting on making this young Targui an active propaganda agent for the French cause, but the choice of a serf to represent the Hoggar tribes must also have shocked the nobles. This official proof of the French missionary’s preferences was such as to wound the self esteem of these proud warriors; it undermined the rules of precedence of a people very much attached to principles of protocol by reason of their ancient customs.» In fact, as we have seen, it was the deliberate thinking and policy of Father de Foucauld to destroy this improper hierarchy based on no merit and real state of service.

« Of very small stature, not attractive, unintelligent, scarcely communicative, Ouksem ag Chikkat was indeed the least representative type of his race. His shifty look, moreover, reflected what he was in reality: a cheat. As events turned out, this Hoggar proved to be unworthy of the choice made of him. In the course of the war, he was to become a fierce enemy of the French.» First disappointment. But if one had to list them all, what pangs of anguish!

« The settling process begun around the hermitage did not develop; the only result was to increase the black population who were also more avid for substantial goods than for spiritual teaching! Furthermore, stimulated by the presence of a Catholic priest in the midst of these tribes of no precise religion, the Muslim confraternities in the meanwhile stepped up their personal propaganda in the Hoggar.

« Then, the Aménokal himself settled at Tamanrasset where the military authorities had a residence built for him. But Moussa only visited his new residence occasionally between long intervals. It has to be said that the Touaregs have little taste for the sedentary life, and that the guarding and rearing of their flocks necessitated frequent moves.

« If the effect of this immediate neighbourhood failed to calm the suspicions of the nobles, the Father and the chief of the Hoggar were nevertheless on very courteous terms with each other. Any offence that might have been taken was, however, cleverly exploited to the Father’s detriment by a very influential figure of the Aménokal’s permanent circle. It was the Arab marabout from Fezzan, Ba Hamou, of the Kadria Muslim religious sect. Originally from Rhat, Ba Hamou was a subject of the Senoussist chief Si Labed, fomenter of the holy war in the Sahara. We shall see further on the primordial role played by this fanatic in the course of the events that led to Father de Foucauld’s death.»

ISLAM : MORTAL RIVALRY.

« Up to the declaration of the 1914 war, there were three Muslim religious sects exercising, or attempting to exercise, their influence over the tribes of the Hoggar. Since the Touaregs for the most part showed little inclination for such a development, the results of this activity were very mediocre. If a few notables were more willing to submit, it was more through simple conformism or ambition rather than through conviction and sincere belief.

« These three sects are: the Kadria, the Tidjania and the Senoussia.

« The Kadria was represented in the Hoggar by the Fezzan marabout Ba Hamou, mentioned above. Two Hoggar chiefs are of particular interest in this domain: the Aménokal Moussa ag Amastane himself and the chief of the Dag Rali, Ouksem ag Ourar.

« Before 1914, the Tidjania sect was the most well known in the Hoggar. Its activity goes back to a time before the arrival of the French in this region. This confraternity had a few members among the notables of the Issakkamaren and Dag Rali serfs.

« There remains the all too famous Senoussia sect which, until 1914, had concentrated its activity on the nomadic Touareg Ajjer wandering in the vicinity of the Zaouïas of Rhât and Mourzouk in the Fezzan.»

Father de Foucauld had seen through the personality of Ba Hamou, having had much to complain of regarding him. He wrote to Colonel Sigonney on the 24th December 1908:

«Ba Hamou, Moussa’s Khodja, or rather his ex-Khodja, for Moussa has half, three-quarters, stood him down, is also very dubious. He is obviously someone to be sent back to his native country of Rhât, but not yet; out of consideration for Moussa, we must wait until he is there [...]. For the present, I believe that Ba Hamou is underhandedly doing us a lot of harm with his talk.» (Amitiés sahariennes, vol. II, p. 178-179).

One is reminded of Jesus’ patience with Judas. Brother Charles de Jésus put up with Ba Hamou with an evangelical patience and maybe with a judicious self-interest too. Knowing the bad influence he exerted over Moussa, he may have preferred to keep him with him to help with his linguistic work and so not involve the Aménokal. In any case, if there is a Judas in this business, our Father exclaims, it is more likely to be Ba Hamou than El Madani.

Vella continues:

« As for the Hoggar nobles, they fell, in Sudanese Adrar, under another marabout influence, that also belonged to the Kadria: that of Si Mohamed Baye Ould Cheikh Sidi Amer, an Arab marabout who, at that time, enjoyed very great prestige among the Touareg tribes of the region.

« A strange story was circulating in Sudanese Adrar, in 1915, at the time when I was there myself with the Aménokal Moussa ag Amastane: Si Mohamed Baye was none other, so it was said, than a Frenchman hiding beneath the appearance of a marabout. He was one of two officers who had disappeared from the Voulet-Chanoine Mission, in the thick of the Sudanese bush in 1900, at the time of the drama in which the former members of this mission were battling against those who had been sent by higher authority to relieve them. Si Mohamed Baye, whose face was always hidden behind thick veils, never appeared, it is true, to his visitors. He would speak to them through a hanging curtain which divided his tent. This detail, together with the fact that Si Mohamed Baye always kept himself at a distance from military posts and detachments, and would counsel, so we are assured, our colonials in the best interests of France, make this story somewhat plausible.

« The fact that Moussa ag Amastane never, at the time of the general insurrection that followed, gave the order for dissidence to the serf tribes remaining in the Hoggar, and that he himself and his noble tribes kept to a cautious rather than bellicose attitude, proves that he had not in fact been badly advised and that his religious initiation had not made him fanatical.»

THE MARABOUT BA HAMOU, SOUL OF A VAST PLOT

In order to extend their holy war movement beyond their favoured regions: Tripolitania, Libya and the Fezzan, the Senoussist chiefs had won over all the sects of lesser influence, but of the same orthodoxy and naturally with the same anti-European aim.

The Kadria marabout Ba Hamou, who originated from Rhât in the Fezzan, hence a subject of Si Labed, a Senoussist chief fiercely hostile towards the French, could not, therefore, be anything other in the Hoggar than an anti-French propagandist, an executive agent for Senoussia and, consequently, a certain enemy of Charles de Foucauld and all that he stood for in the Hoggar.

The fact that this person belonged to a fanatical sect and that he was constantly present around the Father from 1914 to 1916 are sufficient proof of premeditation and murder in the killing at Tamanrasset. It is not simply a coincidence that it was someone else from Rhât, also a subject of Si Labed and of the same Senoussist dependency, the traitor El Madani, who played the role we know.

The marabout Ba Hamou, moreover, was to disappear from Tamanrasset at the same time as the Dag Rali dissidents, to return there in 1918 and die there in 1922.

An educated Muslim, Ba Hamou was Moussa ag Amastane’s right hand man, counsellor and director of conscience as it were, and so was excellently well placed to demolish Father de Foucauld’s priestly mission. Which he did not fail to do with a remarkable skill and tact characteristic of all Muslim marabouts.

Playing a double game, this treacherous marabout knew how to capture the confidence of his French “ friend ”. He passed on minor details to him and even gave him very useful help with his work on Touareg writing. But, at the same time, he fostered and attracted everything that could harm his cause.

Thus it is that he managed to bring the Hoggar chiefs to the Muslim religion, a religion whose rites they practised but with no great conviction. He saw this as a way of increasing his authority over his subjects and of extending his personal influence beyond his territory. Under this religious sway, the Aménokal had even envisaged the building of a mosque at Tamanrasset. The 1914 war had prevented this plan from being carried out, but the very intention to do so marked hostility towards Charles de Foucauld’s cause, and it was the effect of Ba Hamou’s secret action.

When, towards 1914, Moussa and his noble tribes left the Hoggar for the Sudanese Adrar, in order to provide for their flocks, the marabout Ba Hamou concentrated all his nefarious activity on the Dag Rali and the other servile tribes who, like him, had remained in the Hoggar. »

Charles Vella (op. cit., p. 43-44)

THE HOLY WAR.

In 1915, the hundred and twenty-five meharists responsible for security in the Hoggar were scattered from the Sudan to southern Tunisia: a worrying situation, explaining « the precautions that the Father had to take at that time, that is to say, the construction of a shelter for the protection of the black population in his vicinity.

In 1915, the hundred and twenty-five meharists responsible for security in the Hoggar were scattered from the Sudan to southern Tunisia: a worrying situation, explaining « the precautions that the Father had to take at that time, that is to say, the construction of a shelter for the protection of the black population in his vicinity.

« As the horizon darkened towards the East, so the activity of the marabouts intensified. Charles de Foucauld judged how sterile his own efforts were from all this insidious propaganda, which gave him cause for bitter complaint. Informed of this state of affairs, the military commandant took policing measures, but they proved to be ineffective because of the complicity of the tribal chiefs themselves.

« If, in the great North African centres, the French administration had been able, with the support of the Caïds and other devoted and sincere natives, to thwart this secret action, it would have been much easier in the southern territories where the tribes are scattered and where they can be up to a thousand kilometres away from the word of command.

« This marabout propaganda was much more effective in the Hoggar for being exercised over subjects temporarily freed from the authority of their absent masters, and much less aware than the latter of the risks entailed in any adventure.»

The holy war, therefore, broke out in December 1914 starting from the Fezzan, preached by the Arab chiefs of the Muslim Senoussiya sect, in the name of its founder Muhammad ibn Ali es-Senousi (1792-1859). As we saw in the previous chapter, the Italian garrisons are routed; those of Rhât and of Ghadamès, isolated posts, abandon their positions and seek refuge in French territory.

« Because of its extremely favourable geographical situation, the Fezzan, thereafter a free territory, has become the meeting place for Senoussist agitators and their satellites. This agglomeration of chiefs and subjects, resistant to European authority on various counts, represents an excellent element of discord, which the Turco-Germans do not fail to exploit against the occupying allies.

« Abandoned by the Italians, the Fezzan is militarily equipped, and the Harka soldiers are enlisted for it and are equipped with the latest weaponry. It seems that Turco-German officers had a hand in this organisation them- selves since, among these native formations, Whites have been seen.»

The Fezzan agitators then lose no time in bringing their efforts to bear on French Saharan territory. After the fall of Djanet, French troops were obliged to beat a strategic retreat:

« It follows that we have to evacuate the whole of the Ajjer region, in order to retain no more than a foothold at Fort Flatters further north. This painful necessity gives serious encouragement to the Senoussist chiefs. Their propaganda and their success have definitely won over the Ajjer tribes, who have been greatly influenced by the presence of Sultan Ahmoud on their side. This Targui chief was formerly the sovereign ruler of the Djanet Oasis and implacable ene-my of the French.» Rather than accept French suzerainty, Ahmoud went over to the Fezzan, awaiting his hour and plotting intrigues. Moussa esteemed and feared him. He will finance the assault on the “Christian marabout”, using El Madani.

The uprising reaches the Sudan: « The Hoggar, which now finds itself isolated, will be the last bastion for the Senoussist headquarters to attack before reaching the goal they are aiming for.» It is then that Father de Foucauld, sensing imminent danger, goes down to Fort-Motylinski in order to advise Constant to withdraw into the mountains. The officer will faithfully follow his advice. Despite the few resources at his disposal, he will put the fort into a good state of defence and will prepare a fortified hideout several kilometres from there. He would like to keep the Father at the fort, but the hermit obstinately refuses and goes back to Tamanrasset.

THE PLOT.

Let us resume Charles Vella’s account: « A void was created around Tamanrasset as around Fort-Motylinski. Only a few black fellahs stayed to tend their fields. The Dag Rali and other serf tribes now prefer to wander in the eastern part of the mountains. It is clear that their moving camp in the direction of the rebel regions has been commanded by events in preparation.

« The meharist group from the Hoggar still find themselves engaged in exterior operations.» They follow Moussa’s camps and flocks to protect them. « Recalled from the Sudan in order to take command of Fort-Motylinski, all I had for its defence were twelve native meharists.» Thus reduced, the garrison can hardly move and is incapable of bringing aid to Father de Foucauld and his Harratins.

« Having established a permanent courier with the Father, we correspond across the mountains, outside the normal tracks. It is Paul Embarek, his black servant, who operates this clandestine courier. His equipment consists of nothing more than a big hollow stick - this is his master’s innovation - in which we place our correspondence. Given the ever more menacing danger, I propose that the Father leave his hermitage and come to Fort-Motylinski where he will be in greater safety. He comes to the post, but does not want to stay.»

Vella, therefore, lets the holy hermit go back to Tamanrasset, « taking with him fifteen 1874 model rifles and four boxes of cartridges, which I had brought with me to give to him for the defence of Tamanrasset’s black population. We were in 1916, and I was never to see the Father again. The defection of his Touareg friends, which was already effective, had apparently been a great trial for him. Well informed as to the causes of the uprising, and having witnessed for eleven years the Arab marabouts’ efforts to circumvent the people of the Hoggar, Charles de Foucauld was now witnessing the conclusion of the tenacious propaganda conducted by his adversaries in religion. He was to be dealt a very harsh blow as both a large-hearted Frenchman and a missionary of ardent faith. It was also the collapse of his hopes of any further evangelisation, which his early disappointments had not quenched.

« We are eventually informed of the presence near Tin Tarabine, a few days from Fort-Motylinski, of the Senoussist war leader, Khaoucen. The Hoggar tribes and the Senoussists, in contact with the Hoggar, seem to be awaiting either the arrival from the Sudan of Aménokal Moussa ag Amastane’s noble tribes, or else a word of agreement from him to make a common assault on Fort-Motylinski. Not obtaining the support counted on from the Hoggar chief, Khaoucen decided to join the latter in Sudan.

« The servile Hoggar tribes, now dissident, found themselves somewhat disconcerted by the loyal attitude of their chief Moussa ag Amastane and by Khaoucen’s change of objective. But always under the fanatical yoke of the marabout Ba Hamou, who never leaves them, and in contact with other Senoussists, the chiefs of the servile tribes are no longer masters of their own actions. Under this relentless hold over them, the vague revolutionary impulses of a moment will give way to declarations of hostility against us.

« It will be under this constant religious domination that the Dag Rali, Charles de Foucauld’s friends for eleven years, will allow this sacrilegious act to be carried out on their territory by the Senoussists - an act which they would not have perpetrated themselves and in which they will not share. The Kadria marabout Ba Hamou, of Fezzan origin and Senoussist obedience, will succeed in convincing them that they must allow the fulfilment of this act willed by Allah.»

And so, urged on by a letter received from a European, mentioned by Laperrine in his report (cf. inset below Martyr of Christendom), Khaoucen decided that the Father should be deftly eliminated. Ba Hamou doubtless served him as a liaison agent.

A bandit by name of Beuh ag Rhabell moved with his troop towards the fortified hermitage. They were accompanied by Kerzou, a Touareg noble from a dissident tribe. A year earlier, he had deserted Fort-Motylinski, where he had been meharist-brigadier and where he certainly met Father de Foucauld. Other Touareg nomads joined the raid as well as a few Harratins, including some whom the “marabout” looked after, helped and treated as brothers, in particular a crop-grower from Amsel by name of El-Madani. He worked at Tamanrasset with Father de Foucauld and so knew all his ways.

HANDED OVER THROUGH TREACHERY.

« The garrison of Fort-Motylinski has been reinforced with a Meharist platoon which brings our numbers up to forty-five men under the orders of the captain in command of the Hoggar region», who is Captain de La Roche. But it reads as though Vella avoided naming him. In fact, he even writes: « Fatality was such that the Father could not count on help from anywhere.» What “fatality”? Vella continues:

« Obeying an instinct of prudence, apparently based more on fear of opposition from the Dag Rali than on an intervention by the post’s forty-five meharists, who were without horses as he knew, the enemy group had left the usual track through the mountains in order to make a long detour to the east and south through the plain, bypassing Fort-Motylinski.

« Informed of this enemy presence in our vicinity, the captain commanding the Hoggar had thought that the raiders were looking for the garrison’s horses, or that we were to expect a forthcoming attack on the post. As far as this officer was concerned, the Father was safe in his impregnable “ stronghold ”. Besides, there was every reason for thinking that the Touaregs would not attempt anything against the French Priest, and no one could foresee the treachery of a Madani.»

« No one could foresee.» Truly? In vain does Vella try to excuse Captain de La Roche; what he adds simply lays the weight of responsibility for fatal negligence on this officer:

« For all these reasons based on plausibility, the Captain commanding the Hoggar had not thought it his duty to authorise me, as I had asked him, to attempt a surprise action when the Senoussist group found themselves level with the post.» (op. cit., p. 61)

The raiders went to the area surrounding Tamanrasset, to the small village of Amsel where, in September, a plot against Father de Foucauld had already been fomented. It was in this village that El-Madani lived, as we have said. This choice of waiting place proves that the part played by El-Madani is not fortuitous, as he claimed. It is even attested that his part was active and decisive:

« For several days, Madani has spread the rumour that the danger is over and that life at Tamanrasset can continue as before. It is possible, therefore, that the Father’s usual companions were taken in by Madani’s lies, but it is even more likely that they were not unaware of the presence of the enemy, camped for two days at Amsel, where they were awaiting the fatal day when the mail is delivered.

« Nobody, however, informed the Father, any more than the meharists, of the danger threatening him. For certain, the Senoussist warriors had told the Blacks nothing of their reasons for staying at Amsel nor of the ambush they were preparing; but this presence should have aroused the fears of the most devoted of them, especially Paul.

« It is also possible that, in order to attenuate the cowardly attitude of these Blacks towards their benefactor, they succeeded in believing that no harm would befall him.» (op. cit., p. 52)

DIES NATALIS : 1st DECEMBER 1916.

On Friday, the first of the month, at about 7 o’clock in the evening, the Father was alone in his place; his door was bolted. Paul Embarek, his servant, was in the village. Two meharists from Motylinski, Bou Aïcha and Boudjema Ben Brahim, had to leave Tamanrasset that same evening for Tarhaouhaout. They had to pass by the Father’s residence to say their farewells and to take his mail to Motylinski. So he was waiting for them...

On Friday, the first of the month, at about 7 o’clock in the evening, the Father was alone in his place; his door was bolted. Paul Embarek, his servant, was in the village. Two meharists from Motylinski, Bou Aïcha and Boudjema Ben Brahim, had to leave Tamanrasset that same evening for Tarhaouhaout. They had to pass by the Father’s residence to say their farewells and to take his mail to Motylinski. So he was waiting for them...

The assailants advanced, after having looted the village of Amsel. Having carefully collected all the various testimonies of this drama, René Bazin made of this a detailed account, which is well known. It is a dramatically powerful account, with the savour and the violet colour of the Gospel of the Passion: like his “unique Model”, Charles de Foucauld was “hated without cause”, arrested through treachery, and “pierced” by the bullet which violently and painfully killed him. Like the lamb being led to the slaughter, he did not open his mouth:

« The raiders were armed with Italian rifles; not all their auxiliaries had weapons. Together, some on foot, others mounted on camels, they advanced to within two hundred metres of the fort; they made their camels kneel down along the garden wall and silently surrounded the home of the “roumis’ marabout”. There were about forty of them. But they had to have someone who knew the Father with them in order to get the door open. El Madani, who knew the habits and the passwords of him who had been his benefactor, approached the door of the fort and knocked. The Father arrived after a moment and, as was his custom, he asked who was there and what he wanted. “It is the letter carrier from Motylinski”, was the answer. As this was in fact the day for the mail to be delivered, the Father opened the door and held out his hand. His hand was seized and held tightly. Immediately, the Touaregs who were hiding near by rushed forward and pulled the priest out of the fort, and, with shouts of victory, they tied his hands behind his back and left him on the terreplein, between the door and the low wall which hid it, guarded by one of the bandits armed with a rifle. Father de Foucauld fell to his knees and remained motionless; he was praying.

« I shall transcribe here, the depositions of the negro servant Paul, together with those of another Hartani, such as they were consigned to the two official reports, and I shall complete them in accordance with the data of various documents.

«“On the 1st December, after having served the marabout’s dinner, I went to my zeriba, situated about 450 metres from there. It was about 7 o’clock and it was dark.

«“Shortly after, just as I was completing my own meal, two Touaregs suddenly appeared in the zeriba and said to me: Is that you Paul, the marabout’s servant? Why are you hiding? Come and see with your own eyes what has happened: follow us! I answered that I was not hiding and that what was happening was the will of God.

«“Arriving near the marabout’s house, I saw him sitting with his back against the wall, to the right of the door, his hands tied behind his back, looking straight ahead of him. We exchanged no words. I knelt down to the left of the door, as I was ordered. The marabout was surrounded by numerous Touaregs; they were talking and gesticulating, congratulating and blessing the Hartani El Madani who had drawn the marabout into this ambush, telling him that as a reward for his work a life of delights awaited him in the next world. Other Touaregs were in the house, entering and leaving, bringing out various objects from inside : rifles, munitions, provisions, chegga (cloth), etc. Those who were surrounding the marabout pressed him with the following questions: When is the convoy coming? Where is it? What is it bringing? Are there any soldiers in the bled? Where are they? Have they left? Where are the soldiers from Motylinski? The marabout remained impassive; he did not utter a word. The same questions were then put to me, as well as to another Hartani, who was apprehended whilst passing through the wadi at that moment.

«“The whole thing lasted less than half an hour. The house was surrounded by guards. At that moment, one of the guards gave the alarm and shouted out: The Arabs are here! The Arabs are here! (the soldiers from Motylinski). Hearing these shouts, the Touaregs, with the exception of three, two of whom stayed in front of me, and another standing on guard by the marabout, turned towards the direction from where these shouts were coming. Almost immediately there was a sharp burst of gunfire. The Targui who was near the marabout brought the mouth of the barrel of his gun close to the latter’s head and fired. The marabout did not move or make a sound. I thought he was not wounded; it was only after a few minutes that I saw the blood flow, and the marabout’s body slid slowly down, falling to its side. He was dead.”» (Bazin, op. cit., p. 453-455)

According to the report by Captain de La Roche, Paul specified: « The Hartani (who was questioned) said there were two soldiers in the bled, who were due to leave Tamanrasset that same evening, for Tarhaouhaout, and that, perhaps, they had already left. No sooner had he said that, than the soldiers arrived on their camels; they had come to greet the marabout. The enemies got down into the trench surrounding the house, and all fired together. Bou Aïcha fell on the spot; Boudjema Ben Brahim wanted to save himself, but he did not make sixty metres before he fell. The moment the meharists appeared, the marabout made an instinctive movement, foreseeing the fate in store for them.» It is then that the Targui in charge of guarding the prisoner, a sixteen-year-old adolescent by name of Sermi ag Tohara, fired his rifle.

Anxious to avoid all personal risk of punishment involved in this fearful mission, the Senoussist warriors had entrusted the execution to this boy, who was rapidly to expiate his crime - he alone! Taken prisoner by the French, he will be killed after attempting to escape.

Paul Embarek continues: « The Touaregs were not long in returning, after having killed the two soldiers who were passing through Tamanrasset and had come to greet the marabout, as was their custom, before taking the route for Motylinski. They stripped the marabout bare of all his effects, then threw him into the ditch surrounding the house. They then discussed what was to be done with his body, and whether or not they should kill me, as a kafer (unbeliever), like my master.»

In fact, Paul Embarek had been baptized by Father de Foucauld.

« On the intervention of the Harratins of the bled and of their chief who, on hearing the gunshot, had run forward, I was spared and set free.» No doubt after having pronounced the chahada. But that is something Paul Embarek will never tell!

« As for the marabout, some wanted to take the body away and hide it, others wanted to attach it to a tree not far from the house, in the wadi, and leave it as food for the dogs of the Chikkat Touaregs of the Dag Rali tribe, whom they knew to have been friendly with the marabout.

« In the end, still other Touaregs with no interest in the question, and who could satisfy their desires by simply helping themselves to provisions found in the house, put an end to the discussion by obliging each one to watch over his share of the loot.

« The marabout’s body was momentarily forgotten. The assassins spent the night eating and drinking. The next day, the discussion began again with no definitive solution reached, and so the marabout’s body was abandoned without being mutilated.

« In the morning, the Touaregs succeeded in killing another soldier, taken by surprise - an isolated soldier who had come from Motylinski, knowing nothing of the drama, and who was going to call on the marabout to bring him his mail from In-Salah.

« At about midday, they left, taking their loot with them. The Harratins then buried the marabout and the soldiers. That evening, I set off to go and inform the post of Fort-Motylinski, where I arrived at midday on the 3rd December.»

A further variant according to the report by Captain de La Roche: « They ate Ben Aïcha’s camel and slept there. In the morning, they were getting ready to leave, when Kouider ben Lakhal arrived bringing the post. The enemies took up their positions, some in the ditch and others on the terrace; they fired at him, but he was not hit. Suddenly, his camel knelt down, and then they threw themselves on Kouider, holding him by his hands and legs. One of them shot him in the back of the head. They tore open the bag and all the letters it contained.»

THE CHAHADA : « RATHER DIE ! »

Was Father de Foucauld killed through haste, as the pacifist biographers would have it, making of this death an “insignificant event”, as the Abbé Six odiously dares to write (Itinéraire spirituel de Charles de Foucauld, published by Seuil, 1958, p. 364), and as Castillon du Perron inclines to let it be thought (op. cit., p. 515)? And again, quite recently, J.-J. Antier: « He died as he lived: discreetly, neither a hero nor a martyr, “vaguely assassinated”, writes J.-F. Six, by petty bandits come to raid. For this reason, neither country nor religious order can take over so ordinary and banal a death, to make of him a hero whose name is engraved on a monument.» (cf. Jean-Jacques Antier, Charles de Foucauld, ed. Perrin, 1997, p. 301).

Or was he killed as an enemy of Islam, out of hatred for the Christian faith? On this point, Vella’s testimony is decisive. He proves that the crime was premeditated, as the decisive action of the holy war declared by the Senoussists. Little by little, the Islamic plot concentrated on the Father because, after two years of war and the capture of Djanet, the only power keeping the Touaregs faithful to France was this “Christian marabout”. In killing him, Islam could resume its expansion and throw the French into the sea.

« Paul Embarek, the Father’s servant, writes Vella, presumably made different declarations on this subject from those which he gave me to hear, on the 3rd December, at Fort-Motylinski, from the very mouth of this native come to announce the death of his master.

« Here is the exact reproduction of the first declaration made by Paul Embarek in my presence:

«“ From the moment he was seized and tied up until his death, the Father simply prayed, absolutely indifferent to what was going on around him.”

« The summons to apostatise, which would have been made, according to another certain declaration of Paul Embarek’s, may very well refer to the ritual Muslim “chahada”, to which the Father would, in my opinion, have been unfailingly subjected. This koranic rule is, in fact, applied in similar circumstances to anyone condemned to death, Christian and Muslim alike, and by the Touaregs as well as by the Arabs. Here are two facts, moreover, which verify this statement: taking part in an expedition in 1915 against Moroccan Réguibat raiders near Taoudeni, I witnessed eleven prisoners being put to death by Aménokal Moussa ag Amastane and his Hoggar tribesmen. For each one of them, the “Chehede Allah” was pronounced. I was able to see personally, in the course of an affair which nearly proved fatal for me, that this Muslim rite was no less rigorously observed by the Touaregs with regard to Christians. The circumstances of this failed execution (mine), were just as fortuitous and its decision just as rapid as they must have been for the Father.

« I have no hesitation, therefore, in writing that it would be absolutely contrary to koranic rites, and to Muslim warrior traditions, for Charles de Foucauld not to have been summoned to pronounce the “chahada”.» That fact is beyond doubt, and we shall see that it was applied a fortiori to Paul Embarek, the Hartani baptized by Father de Foucauld.

« The response to the summons to pronounce the chahada is as follows: “I swear that there is no God but Allah and that Mohammed is Allah’s prophet”. Put to a priest, this injunction assumes a very particular character in the sense that it invites him to recognise another God than the one he serves. One arrives at the conclusion, therefore, that to answer this summons with silence is in reality a refusal to abjure. It matters little, therefore, whether or not the Father pronounced the words baghi-n-mout (I wish to die) or garib-n-mout (I am going to die) which have been attributed to him. Taking refuge in a prayer which he knew to be his last is indeed a refusal to “acknowledge Allah”. This prayer in itself signified, without there being any need to express it otherwise, that he preferred death to any submission other than to Christ.»

THE KISS OF JUDAS : EL MADANI

Referring to a certain law setting a time limit for prosecutions, the military authority involved did not punish the traitor El Madani as he deserved. Madani eventually died at Ghât of a natural death, in 1951. Thus, this criminal fanatic was able to travel freely throughout these regions for many a long year, glorying in his anti-Christian and anti-French exploit. For this lofty deed, he enjoyed the consideration, veneration even, of his co-religionists. Madani never failed to exploit this prestige for the benefit of his sect and the detriment of French authority.

« Madani seems to have claimed, in his defence, that he had been forced by the Senoussist warriors to play the role which we know he took. But the fact that he was taken in 1920 with weapons in hand against the French, proves that in reality he was not only a conscious fanatic but also a determined enemy of France.

Madani ag Soda was born in the Djanet oasis, today Fort-Charlet, in the Touareg territory of Ajjer. He was the natural son of a black mother by an Oraren Targui, his father. The matriarchy practised among the Touaregs classed individuals of this type as serfs attached to the glebe, cultivating palm trees and gardens throughout the oases of Saharan Algeria and Tripolitania for the benefit of their Arab or Touareg masters.

The Djanet oasis, Madani’s birthplace, was dependent, before French occupation, on the suzerainty of Sultan Ahmoud, that Targui chief who preferred to abandon his rights and property and cross the Fezzan frontier rather than submit to the French. Sultan Ahmoud settled at Ghât, a neighbouring Fezzan oasis, from where he continued to supervise his former fiefdom and to collect the customary tithe from his vassals.

Contacts continued, therefore, between French subjects and their former master as well as with the local Senoussia chief, Si Labed. With the fall of the Italian posts, the Fezzan gained a state of independence, which made it possible for even closer contacts to be forged between our colonials and the Touareg and Senoussist chiefs of this neighbouring enemy territory.

For his part, Madani, although settled in the Hoggar, made frequent visits to Rhât, and we may suppose that the reason for his visits was not simply to acquit his obligations as a vassal with regard to his master. From that moment, he was an intelligence agent for our enemies. The Senoussist chiefs could not find a better auxiliary to serve them in the Hoggar. It is quite probable that Father de Foucauld’s fate was decided during one of those visits to Rhât.

Charles Vella (op. cit., p. 52-53)

THE RENEGADE.

Paul Embarek was present at Father de Foucauld’s death: he is therefore the only eyewitness. But he relates the events in several different ways. René Bazin writes:

« Five weeks after the assassination, when the information collected was taken to In-Salah, rumour had it that the assassins had enjoined Father de Foucauld to apostatize, by reciting the chahada, that is to say the Muslim prayer formula, and that he had refused: a letter addressed to M. de Blic, telling him of his brother-in-law’s death, is proof of this.» (op. cit., p. 462)

It is a pity that René Bazin did not reproduce this letter, but we find an echo of it in the letter written by Marie de Blic to Dom Augustine, a Trappist at Our Lady of the Snows, dated 4 February 1917: « We have received several accounts of these tragic events; in one of them (sent by Captain Depommier, from In-Salah on the 9th January), it says that the assassins wanted to force the Father to pronounce the Muslim prayer, and that, faced with his refusal, one of them shot him in the back of his head with his rifle, killing him point-blank.

« The captain, who greatly loved my brother and had known him for eight years, told us that he must have smiled at this death - ideal for him! It is indeed martyrdom bringing a dignified end to the sacrificial life of Father Charles de Foucauld. What a consolation for us and what an example for our children.» (Lettres à mes frères de la Trappe, Cerf, 1969, p. 402-403)

Bazin observes that neither the report of Captain de La Roche nor that of Captain Depommier mention the fact. « But that, during the half hour when Father de Foucauld was subjected to ill treatment and insults before being killed, he would have been summoned to abjure remains highly likely for two reasons: firstly, as a Saharan officer wrote to me, because the contrary would be the exception among the Muslims, who never separate death from the chahada; in the second place, because the words reported by the negro Paul Embarek were repeated by him in 1921. “In my presence, the enemies simply asked: where is the convoy? where are the people? After the death of de Foucauld, I heard them speaking among themselves: he was asked to pronounce the chahada but he answered: I am going to die. This last phrase was said by some of the men of the Aït-Lohen, whose names I do not know” (source: letter from Captain Depommier to the author, 8 March 1921).

« Today, therefore, it seems probable that Father de Foucauld was summoned to abjure, according to custom. It seems certain that the assassination did not follow immediately after the refusal: it was the arrival of the meharists from Motylinski that proved to be the decisive cause of his death. The original idea had been to make a prisoner of Father de Foucauld; the opportunity occurred to kill him, and so he was killed, for fear that he escape or be set free. Hatred of the Christian, however, could not be considered alien to this drama, and the servant Paul is of this opinion since, in his statement, he says that they threatened to kill him too as an “unbeliever” (kafer).»

Kafer, in koranic Arabic, does not mean “unbeliever” but “apostate”. That at least is Brother Bruno’s interpretation, which in the circumstances proves to be exact since Paul Embarek was baptised! It is understandable that he preferred not to insist on that, and that he even passed in silence over this major circumstance of the marabout’s death... whose fate he should have shared!

Father de Foucauld died not only a martyr of the faith but of charity too. Bazin in fact adds: « It also needs to be remarked that Father de Foucauld, having constructed the fort so that the poor village people might be sheltered with him, would never abandon them, and his stubborn charity, therefore, was his death.» (op. cit., p. 462-463)

THE HOST WILL NO LONGER RADIATE OVER THE HOGGAR.

René Bazin again writes:

« When the raiders had withdrawn towards Debnat (west of Fort-Motylinski), the victims’ bodies were not left abandoned for long. The Harratins were not afraid to come forward and bury the victims in the moat of the fort, a few yards from where Father de Foucauld had fallen. The Father’s body was not untied from the ropes that held his arms behind his back until after he had been laid in the ditch. The Harratins knew that the Christians put their dead in a coffin, and so they placed stones around the corpse, sheets of paper and fragments of wooden boxes. Then they walled up the door of the fort.

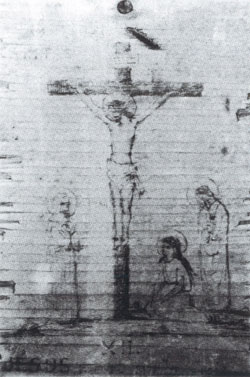

« The first thing done by the Commandant in charge of the Hoggar section was to go in pursuit of the band of fellagas. The raiders were engaged in combat on the 17th December and several of their men were killed. It was not until the 21st December that Captain de La Roche was able to go to Tamanrasset, accompanied by a sergeant and a soldier. The first thing he did on his arrival was to identify the graves. He added a layer of earth to that covering the bodies, and planted a wooden cross over the Father’s grave. Then, for those who had died for France, he paid due military honours. And only then did the officer enter the fortified hermitage. « The interior of the casbah had been ransacked ; the ban-dits had taken away everything of value that they could. All the rest had been overturned, torn up and partly burned. The whole library and all the papers had been scattered all over the room which served as chapel and sleeping room. Below is a list of the various items found:

« A few objects for divine worship, pious objects, devotional books, the four volumes of the dictionary and the two volumes of poetry could be restored in their entirety; office furniture, a tropical helmet, a camp table, a camp bed, a large thermometer, a certain number of letters written by the Reverend Father during the day of the 1st December, sealed and stamped, etc. »

Some time later, in February 1918, a detachment of Saharan troops, operating against the dissidents, and killing seven of their men, found various items at an encampment, three hundred kilometres to the east of Tamanrasset: sandals, kitchen utensils, scissors and other different objects, all of which had belonged to the Father.

« Among the “ objects for divine worship ” and the “ pious objects” found in the fort, there was a rosary having belonged to the holy priest; a way of the Cross made of boards on which very fine pen drawings of the Passion scenes had been etched; and a wooden cross also bearing a very beautifully drawn image of Christ’s Body. Kicking the ground over where all sorts of objects had been thrown, the young officer discovered in the sand a very small monstrance, in which the Sacred Host still appeared to be enclosed. He picked it up with respect, wiped it and wrapped it in a cloth. “I was very put out, he related later, because I felt that it was not for me to be carrying the Good God in this way”. When the time came to leave Tamanrasset, he took the small monstrance, placed it in front of him on the saddle of his méhari and travelled thus for the fifty kilometres separating Tamanrasset from Fort Motylinski: it was the first ever Blessed Sacrament procession in the Sahara. Having arrived at the station, he was greatly embarrassed. Along the way, M. de La Roche remembered a conversation he had had with Father de Foucauld. How he had said to him: “You have permission to keep the Blessed Sacrament, but if any misfortune were to overtake you, what would you have to do?”

The Father had replied : “There are two solutions: make an act of perfect contrition and give yourself communion or else send the con-secrated Host by post to the White Fathers.”

He could not bring himself to take this second course. So M. de La Roche called a non-commissined officer at the post, a former seminarian who had remained a fervent Christian, and asked his advice. He thought it best that the one should give communion to the other. The officer “put on white gloves which he had never used” to open the monstrance and make sure that he was not mistaken, that the Host was really there. It was indeed, just as the priest had consecrated and adored it. The two young men asked each other: “Will you receive it, or shall I?” The non-commissioned officer then knelt down and received communion.» (Bazin, op. cit., p. 463-465)

MILITARY PACIFICATION OF THE HOGGAR.

Lieutenant Vella ends his study thus:

« The attack on Tamanrasset was immediately followed by other hostile acts against the French: horses were taken from the Fort-Motylinski garrison; isolated méharists were massacred; the post and its communications were harassed.

« The Dag Rali were more prepared than the others for this kind of subversive action thanks to the marabout Ba Hamou, who was always with them, and were therefore more fierce in their attacks against us. To them, we owe the loss of several méharists including a number of Frenchman. One of them, the company sergeant-major Piétri, wounded and taken prisoner, was savagely finished off just as he was talking with Chief Ouksem ag Ourar. The young Ouksem ag Chikkat, the Chief’s nephew, whom the Father had taken to France in 1913, stood out particularly in operations against us, in which he was wounded moreover.

« Méharist reinforcements arrived from other regions, but they were not enough to put down the movement prevailing everywhere, despite the murderous combats courageously waged by our small detachments under extremely difficult conditions in the mountains.

« Alarmed by the general uprising of the Sudanese tribes followed by the siege laid to the posts of Ménaka and of Agadès, and fearing for Fort-Motylinski, whose strategic interest is emphasised by these grave events, the top military command took the necessary measures.»

General Lyautey, who was then War Minister, decided to return Laperrine to the Sahara, with the title of Superior Commandant of the Saharan territories. Laperrine was at that time head of the 46th Infantry Brigade, at La Maisonette, on the Somme. On the decision of the War Ministry, he quit his front line command on the 7th January 1917, received his new assignment on the 12th and was back in Africa on the 21st.

« The General called on tried and tested former officers of the Sahara, two of whom knew the Hoggar through having been in command there, each for several years. The two were Commandant Sigonney and Captain Depommier.

« The experience of such officers immediately bore fruit. One of them, Captain Depommier, did not hesitate, at the head of a small Méharist detachment, to go to the Agadès region, in Sudanese Aïr, where the Aménokal Moussa and his noble tribes still held out. There, he also found the Harka enemy, whose chief, Khaoucen, was trying to win the Hoggars over to the Senoussist cause.

« Depommier’s Méharist detachment, therefore, met up with the Aménokal Moussa ag Amastane, in Aïr, in the month of March 1917, at just the right time. The post of Agadès, in the meanwhile, was cleared by the colonials. Only one part of the nobles had gone over to the dissidents: the Taïtoqs, furious raiders for whom subordination to the French weighed heavily. For many long years, these Taïtoqs had sought to detach themselves from Moussa’s authority. Already in 1915, I myself had been given the task of going in the direction of Ménaka, in Aïr, to win them back.

« Captain Depommier found the Hoggar chief in a very delicate situation. Pulled towards dissidence by the Senoussist war leader, who was near him with a very strong troop of superior weaponry, and by those of his own people who thought that the time for independence had come; worried, on the other hand, by the lack of military command in the face of events in the eastern Sahara, the Aménokal held talks and temporises, still trusting in the destiny of France.

« The unexpected arrival of this detachment made everything possible for him again. He immediately won them over and, resuming his full authority, which had wavered for a moment, he assembled all his people, except for the Taïtoq fraction, who will follow a few months later.

« Before returning to the Hoggar, Moussa sets his warriors on Khaoucen’s Harka, and Khaoucen has to seek shelter in the mountains. The military command will once again send Moussa and his men to Aïr to take part in operations against Khaoucen who, this time, will be definitively routed.

« The return of the Aménokal Moussa ag Amastane to the Hoggar obliged the serf tribes to cease their hostilities against us. The Dag Rali chief, Ouksem ag Ourar, wanted to be the first to beg the “aman”.

The Hoggar dissidence will come to a complete end at the beginning of 1918, with the somewhat reluctant return of the Taïtoq and Aït Lohaïn tribes.»

WHEN THE FRENCH ARMY EXORCISED THE DEMONS OF ISLAM

In the months following [the pacification of the Hoggar, at the beginning of 1918], the military commandant decided to employ the Hoggar tribesmen in re-establishing order in the Ajjer territory still under Senoussist control. Dissident activity overran the Ajjer region, reaching the oasis of the North as far as El Goléa via the Tadmaït, and eleven Frenchmen were massacred.

Still head of Fort-Motylinski, I was designated, in October 1918, with seven native méharist volunteers, to accompany two hundred Hoggar Touaregs and their Aménokal Moussa ag Amastane, to a meeting point, where we would be joined by a Méharist detachment from In-Salah, under the orders of Captain Depommier.

The party’s objective was to retake Fort-Charlet (Djanet), which had been abandoned since 1916. On the 28th October 1918, the French flag was once more flown over this post, which had been so gloriously defended two years before by the garrison sergeant major, Lapierre. The enemy bands of the Senoussist chiefs Ahmed Chérif, Si Labed, Abdesselem, then the Touareg chiefs Ahmoud, Boubékeur ag Allégoui and Brahmin ag Abakada, the treacherous murderer of the French, kept out of sight in order to entrench themselves in upper Tasili.

Peace negotiations were immediately entered into between the Aménokal Moussa ag Amastane and Sultan Ahmoud, master of the situation. Moussa obtained an agreement for an interview with Sultan Ahmoud high up in the mountains in his own camp.

Dressed as a Targui and veiled, I was secretly present at these negotiations with our fiercest enemy. It was a voluntary mission “ at my own risk and danger”, to use the very terms of the party commander, Captain Depommier. Since he himself could not take responsibility for such a mission, he will make no mention of it in his report. Sultan Ahmoud, who would have been seventy at the time, died before making his submission. He had sworn “ to die without seeing a Frenchman”. But I took “ the tea of friendship ” with him and the Hoggar chiefs, sitting on his own cover.

Although it had been agreed that the chiefs of the opposing camps would not be accompanied by more than twenty warriors, Sultan Ahmoud brought with him his whole troop including all those who had taken part in the raid on Tamanrasset, Madani too. All the nearby rocks were decked with rifles and bayonets. Behind us, the camp was closed. After long hours of discussions, occasionally very lively, Sultan Ahmed promised to cease hostilities and to return to the Fezzan.

But we were hardly on our way back to the Hoggar than his warriors robbed a convoy of provisions destined for Fort-Motylinski, between In Salah and the Hoggar.

For another two years, despite the promises undertaken, Sultan Ahmoud will continue to harass our posts and detachments. The Hoggar people, for their part, stay calm, but this agitated neighbourhood gives no peace to those in command. Fort-Charlet has to be abandoned once more.

Faced with this ever alarming situation, fostered by the Senoussist chiefs, the masters of Tripolitania and of Libya, the military command decided on a further expedition into the Ajjer country. A party under the orders of Commandant Sigonney, military commander of the Oases Territory, set out from Ouaregla in June 1920, with Djanet as their objective once more. The Hoggar Touaregs will join this party en route and, acting under my orders, will once again take part in these operations.

Fort-Charlet was re-occupied for the second time on the 20th July 1920. The Sigonney party reached the North again. It was my mission, as the only Frenchman among one hundred and forty Hoggar Touaregs and thirty native méharist regulars, to pursue Sultan Ahmoud’s Harkas who held the uplands, and break them up. After an eight day operation in the Tassili and on the Fezzan frontier, and a murderous battle in the impracticable gorges of Assakao where the harassed enemy had taken refuge, the Senoussist bands, though superior in number, were thrown out of our territory.

Among those of the enemy who met their death were three Oraren Ajjer chiefs affiliated to the Senoussist sect and attached to Sultan Ahmoud, two of whom, Chebbeki and Toumi, had, together with Ebeuh ag Rabelli, led the expedition against the hermitage of Tamanrasset in 1916. Madani, the traitor. picked up from among a group of defeated warriors, was only wounded. Entrusted to be guarded by the Hoggar Brahim ag Doua of the Adjouh-N-Tahélé, he fled under cover of the night during the battle, thanks to his guard’s complicity.

The happy results of these operations were 1° to put an end to the disastrous agitation of the Senoussists, by chasing out the troops of this fanatical sect once and for all; 2° to bring back the dissident Ajjer tribes under our authority; 3° to punish severely the perpetrators of Father de Foucauld’s murder; 4° finally, to put a stop to the activity of the Senoussist Muslim religious confraternity in our territory by rehabilitating the French and Christian presence in these regions.

This restoration of order in the Ajjer region, due to the sacrifices in human life accepted by the Hoggar Touaregs at Assakao, effectively marked the defeat of the great Tripolitanian and Fezzan marabouts, whose first act in the Hoggar had been to bring down the French representative of an opposing religion.

And though the assassination of Charles de Foucauld was perpetrated through the treachery of certain Hoggar tribesmen, this death was avenged by the Hoggars themselves.

Charles Vella (op. cit., p. 57-59)

THE SEAL OF LOVE

Father de Foucauld could have died in 1908, of exhaustion: he came very close to it! And he really thought that the moment had come. If that had been so, he would hardly be spoken about.

With those of great heart, it can be said that death is the seal of their virtue : that is why it marks a starting point, being the sacrament of their fruitfulness. With the saints, death comes as the crowning of their imitation of Christ And so it is with Father de Foucauld. Death came to harvest him, in the way he had so much desired and expected: that of martyrdom. Those today who want to portray this martyr of Christendom as a pure mystic simply enamoured of spirituality are travestying the truth out of hatred for this political and French colonial doctrine, which was part and parcel of his life and message. Because of this hatred, they do not hesitate to cover over this whole part of his life, even if it means making a futility and absurdity of his death. For them, “destiny” intended that he should die in this absurd manner, in a fortress, when he was a man of love; beside boxes of munitions and rifles, when he was a man of peace... We must react against this betrayal of his message, and assert that Father de Foucauld died as God wanted him to die: as a martyr.

As for the spiritual significance of his death, it has to be said that he did not die to “redeem” souls, strictly speaking. His doctrine, his devotion to the Sacred Heart was not, as Six remarked (op. cit., p. 344, and 345 note 65), a doctrine of expiation but a doctrine of mercy. It cannot be said that he offered his life to expiate for sins, no. Nor to witness to the truth, as was the case with the Apostles, for example. Not even to witness to the truth of his mission, like Joan of Arc. Nor even to arouse the inert masses. Martyrdom can have many different meanings. For, when a man has worked all his life to bring the Christian people back to the truth, to virtue, he feels that he has nothing better to hope for than to die, and perhaps his death will come as the shock that will reawaken, if God wills, those who remained indifferent to his preaching throughout his life.

With him, it was not like that. It has to be said his death was given him by God, as he himself wanted it: a death through love of Jesus, for love of Jesus, a death of love, in a perfect conformity. Since he wanted to imitate Jesus, and since his love was wholly of imitation, Jesus gave him this supreme imitation. Rather like Saint Francis of Assisi receiving the stigmata of the Passion through meditating on Christ’s Passion. It is the Christus factus est obediens usque ad mortem, mortem autem crucis, that would need to be sung here: Christ made Himself obedient, He who was God, and He not only became man, but the servant and the slave, and descended still more, even to the shame of death on the Cross. It is the example given by Saint Paul to the Philippians (Ph 2. 5-11). Humility is no mediocre bourgeois virtue: it is to descend and descend and descend to abjection. And the final abjection is death on the Cross. Father de Foucauld desired to descend that far: «Think that you are to die a martyr, stripped of everything, stretched out naked on the ground, unrecognizable, covered in blood and wounds, violently and painfully killed, and desire that it be today.»

This note, written at Nazareth in 1897, is truly like a prophecy of what was to come. Now, as Six remarked, Brother Charles underlined in his notebook that same day, these very moving words: «If only Jesus told me that He loved me, but He never tells me that!» It is from the very depths of spiritual dryness, therefore, that he drew the greatest love. And this greatest love was transformed as though into a prediction, a light cast on his future.

Only, it is possible to write on paper: “ Think that...”, and then die in one’s bed. But when one has written, in 1897, that is twenty years in advance, the very way in which God will have us die, God’s providential Will is there to witness to the holiness of His servant. What he had thus foreseen, in his desire to conform with Jesus, is what God gave him. And not only did he write it one day, but he lived by it every day, until it actually happened! A thousand marks of this are to be found in his correspondence, but we also have the deposition of this “Brother Michael” who had spent two and a half months with him in 1906:

« He would have liked to give to Jesus Christ the greatest proof of affection and of devotion that it is possible for a friend to give to a friend, by dying for Him as He died for us. He desired and he earnestly asked God for martyrdom, as the greatest of all benefits. The prospect of an immolation, the beauty and grandeur of which, exalted his generous faith, transformed his ever firm and ardent words, into veritable songs of joy: “If I could one day be killed by the pagans, he said, what a beautiful death! My very dear brother, what honour and what happiness, if God would answer my prayer!”»

This desire went back to the days when, in Armenia, he had seen the Christians savagely killed by the Turks. He then understood that his place was not to be among the Trappists, spared through self-interest, but in the midst of these poor Christians massacred by the Turks out of hatred for the faith. Now, he was massacred by order of this same Turkish government, out of hatred for the faith...

One of his notebooks has come down to us from his time at Tamanrasset, a sort of little memento which begins with these words:

« Live as though you hsd to die as a martyr today.»

At the end of the note book, there are three prayers which insistently repeat the same supplication. In the second prayer, he lets it be understood that, in a prophetic light, Our Lord had shown him what his death would be. In advance, he forgives his assassins:

«My Lord Jesus, You have said: “No one has greater love than he who lays down his life for his friends”, and I desire with my whole heart to give my life for You. I earnestly entreat this of you. Thank you for having given me this hope. Allow me to die giving You the greatest possible glory, in You, through You and for You! Holy Virgin, Saint Joseph, Saint Magdalen, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Peter and Saint Paul, Saint Stephen, my good angel, come to our aid! My God, forgive my enemies and grant them salvation! » (Carnets de Tamanrasset, p. 178)

Another text is less well known: a letter from Father de Foucauld to the Marquis de La Roche-Thulon et Grente reveals that, thirteen years before his martyrdom, he already foresaw the possibility of dying the same death as his former friend of Saint-Cyr and Saumur, the Marquis de Morès, assassinated in 1886 (Amitiés sahariennes, vol. II, p. 376):

«Beni Abbès, 18 March 1903.

«Monseigneur Livinhac has sent me your letter. Yes, I am among those people who killed my friend, avenging myself and avenging him by paying good for evil, trying to give them eternal life.

«This dear Morès, whom I think about and pray for every day, is helping me in this. In heaven, at the heart of eternity, the immense charity in which he is immersed, he has nothing but prayer and love for those Muslims who shed his blood and who will probably shed mine. But we are working together, he up above in glory, and I here below, at the same work of salvation and of love. Help us with your prayers!

«I shall pray for your friend Abd El Aziz. How much I pray for those who loved and who will love this very dear Morès! «Charles de Jésus (Foucauld).»

Finally, one simple phrase written to Joseph Hours, at the beginning of the war, says it all: «Let us offer ourselves as victims»...

There is more. Not only did he desire martyrdom, but he felt death coming, and he desired it with a great love for Jesus. From the age of fifty, he regarded himself as old, and he found that death was slow in coming. One day someone said to him that life was short; and he answered: «Yes, so they say, but it drags on and on and on...»

He wrote to Marie de Bondy:

«It is the solitude that increases; one feels more and more alone in the world. Some have left for France; others have a life that is more and more apart from ours: one feels like the olive left alone at the end of a branch, forgotten, after the harvest. At our age, this biblical comparison comes frequently to mind, but Jesus stays! Jesus, the immortal Spouse who loves us, as no human heart can love. He remains now; He will always remain; He loves us at this moment, and He will love us until our last sigh. If we do not repel His love, He will love us eternally.» (1st September 1910)

If ever a man was ready to die, it was he, as is shown by the letters he wrote on the very day of his death:

He encourages Louis Massignon, this ever loved son who moved, however, towards another vocation than that he had hoped for him: For the moment, he is in the Dardanelles:

«Very dear Friend, very dear brother in Jesus,

«Moved at the thought of the greater dangers you will perhaps incur, and which you are probably already incurring. You did the right thing in asking to be transferred to the troop. One must never hesitate to ask to be posted where the danger, the sacrifice and devotion are greatest. Let us leave honour to those who want it. But let us always ask for danger and trouble! As Christians, we should set an example of sacrifice and of devotion. It is a principle to which we must be faithful all our life, in all simplicity and without asking ourselves whether pride enters into this conduct. It is a duty: let us do it, and ask the Beloved Spouse of our soul to do it in all humility, love of God and of neighbour...

«If you die, God will look after Madame Massignon and your son without you. As He would have looked after them through you. Offer your life to God through the hands of our Mother, the Most Blessed Virgin, in union with the Sacrifice of Our Lord Jesus Christ, and for all the intentions of His Heart, and walk in peace. Have confidence that God will give you the best fate for His glory, the best for your soul, the best for the souls of others, since you ask only for that; and since all that He wants is what you want, fully and unreservedly.» (quoted by Bazin, p. 450)

He takes up his pen to write to Madame Raymond de Blic, his sister. He tells her news but he does not speak from the bottom of his heart. Above all, he does not want to cause her anxiety... Again, a long letter to Laperrine, very relevant, with admirably precise strategic considerations... Finally, one last example of holy tenderness: he writes to Marie de Bondy, his dear spiritual mother. It will be the 734th and last letter addressed to her! What a magnificent testament of a great heart all burning with love of Jesus and, in Him, of one’s nearest neighbour!

Here is the essential of that letter:

«How could you not feel the weight of years, you for whom they have weighed double through trials, for so many years. How could you not feel crushed, after the anguish of these last two and a half years of war and constant anxiety for France and for John! These sufferings, these anxieties, both old and recent, accepted with resignation and offered to God in union with the intentions and sorrows of Jesus, are, not the only thing, but the most precious that the good God offers you to enable you to arrive before Him with your hands full. No doubt, you find that your hands are empty and I am very happy about that, but my firm hope is that the good God will not be of your opinion; He has given you too great a share in His chalice here below and you have drunk from it too faithfully for Him not to give you a very great share in His heavenly glory too. Our self effacement is the most powerful means we have of uniting ourselves to Jesus and of doing good to souls; that is what Saint John of the Cross repeats on nearly every line. When one is able to suffer and to love, one can do a lot - the most that is possible in this world. We feel when we are suffering, but we do not always feel when we love, and that is an extra great suffering! But we know that we would want to love, and to want to love is to love. We find that we do not love enough. How true that is! We can never love enough, but the good God who knows the mud in which we are steeped and who loves us more than any mother can love her child, has told us - He who never lies - that He would never drive away one who comes to Him.»

Written shortly before the drama, it is the desired obliteration... When the Senoussists asked him a few minutes later to abjure his faith, what could he answer other than «I prefer to die; I wish to die; I desire to die»? It is the fulfilment of all his hopes. And to die through love of Christ, what could be greater! Dassine will say, after his death: « The marabout must have gone straight to Heaven, the day when God called him to Himself.» Of that, we are fully convinced.

CCR n° 304, december 1997

MARTYR OF CHRISTENDOM

Charles Vella thus concludes his study on “ The real causes of the assassination of Father Charles de Foucauld ”: «Contrary to what has so often been written, it is not an isolated fact attributable to a few half starved nomads drawn by easy loot, nor is it the unconscious reaction of a crazy young warrior, but the premeditated suppression of a religious adversary, and that is the real reason why the grandmasters of the Senoussia Muslim religious confraternity extended the “holy war”, started in neighbouring Fezzan, to the Hoggar.» (op. cit., p. 51) The inquiries made by the officers stationed in the Sahara, immediately after the Father’s assassination, corroborate Vella’s conclusions.

From Captain Depommier.

« Among the basic motives behind the assassins’ action is certainly fanaticism: “war on the Roumis!” For a long time, propaganda in favour of the holy war had been active in the region; numerous propagandists came from the East, from the Senoussists, and had won over to their cause the men of the Ait-Lohen, a Hoggar tribe from the bordering region of Azdjer. Father de Foucauld was aware of all this [...].

« The leaders of the assassin bandits were strangers from Azdjer, joined by Hoggar (Ait-Lohen) fanatics, won over to the cause of holy war, and living more than a hundred kilometres away from Tamanrasset on the other side of the mountains. It is not surprising, therefore, that they could easily gain help from one or several fanatics, so numerous in Islam, from among the Hartanis, negroes of an intrinsically servile temperament.

« Nothing so far, allows one to believe that a single imrad or Touareg noble from the Koudia region was in favour of the murderers’ plan. The event, however, is still quite recent, and the wise advice of prudence is that time should be allowed to complete its work of investigation, before giving a positive answer on this point...

From a general point of view, it can be said that at the moment of Father de Foucauld’s assassination, every heart in the Hoggar had been won over to our enemies’ cause, and that their dearest wish was for us to disappear from the region very soon and for good.

« Motylinski, 11 September 1917.

« (signed) Captain Depommier.»

From General Laperrine.

Following the official report, General Laperrine dictated a note to be added, which in its conciseness leaves no hovering doubt :

« In my opinion, the assassination of the Reverend Father de Foucauld has to be linked to the letter found at Agadès, among Kaoucen’s papers, in which a European (Turk or German) advised him, as a first measure, before stirring up the populations, to kill or to take as hostages Europeans known to have influence over the natives, and native chiefs devoted to the French.

« Ouargla, 20 October 1917.

« For General Laperrine, Commandant in chief of the Saharan territories,

«(signed) Bettembourg.»

(quoted by René Bazin, p. 457-460)

Father Nouet, of the White Fathers, thus sums up a conversation he had with General Laperrine on the 7th September 1919:

« Turkey, pushed by Germany, wanted to get the Touaregs to rebel against us first, followed by all the desert tribes. The agents of this policy very soon realised that their aim was unattainable for as long as Father de Foucauld remained among the Touaregs of the north, whence his influence radiated. They decided, therefore, to capture him and hold him as a hostage, but not, according to the General, to put him to death. A group was sent on its way to Tamanrasset, etc.»