The Catholic Church in the United States

I. Pioneer days

IN British America, Catholicism and religious freedom have been associated from the very beginning. In fact, George Calvert, a former Secretary of State of James I and Peer of Ireland under the name of Lord Baltimore, converted to Catholicism in 1625. If he wanted to found a colony in America, it was with the intention of establishing a model society where Catholics and Protestants would live side by side in perfect equality. In 1632 he equipped two-hundred families, most of whom were Catholic, so that they might take possession of the territory granted by the King: today it is composed of present-day Maryland and part of Pennsylvania. Two Jesuits accompanied the expedition as chaplains. Lord Baltimore died a few days before they set off, but his sons carried on with the enterprise.

His utopia, a land of tolerance that would thrive among other colonies that were handed over to the fanaticism of the Protestant sects, lasted no longer than ten years. When religious passions awoke, his heir thought that he would quell emotions by appointing a Protestant as governor! He also thought it would be effective to have the Assembly pass the famous Act of Tolerance of 1649, which « is the oldest text from American territory devoted to freedom of worship. » This freedom, however, was only to the advantage of the Puritans and Episcopalians, who ended up seizing power and... repealing the Act of Tolerance! The historian Robert Sylvain sums up what happened afterwards: « Where the most absolute respect of other people’s opinion prevailed on matters of religion, religious freedom disappeared and Catholics were deprived of all the rights they had previously enjoyed. A law of 1704 forbade Catholic priests to say Mass publicly, to fulfil any duty of their ministry, and to convert people. That was not all: Catholics were pushed to the bottom of the social ladder and were banned from all relations in society. They were forbidden to walk in front of the building called the State House and to frequent certain districts of Baltimore. » To cap it all, the third Lord Baltimore apostatised in 1713 in order to find favour with the King of England.

Nevertheless, Providence allowed that a family of influential notables in Maryland, the Carrolls, remain faithful to the Catholic Faith. They had the plan of taking refuge in Louisiana in 1751, but Louis XV did not authorise it, thus they made the best of it. As they had remained firmly attached to their convictions throughout the upheaval, they won the gratitude of the Catholics who came from more modest backgrounds. They garnered the esteem of some Protestants as well, particularly the Quakers, who had just founded Philadelphia and the neighbouring colony of Pennsylvania. The Jesuits were able to find refuge there and open a few schools.

THE CARROLLS, CATHOLIC PATRIOTS

When the colonies rose up against the Crown of England, the Carrolls immediately took up the cudgels for their compatriots. They hoped to receive the right to exist in exchange, as Charles Carroll, the head of the family at that time, admitted. He was also a friend of Washington, Jefferson, and Adams: « I zealously adhered to the revolution, he would say, in order to obtain both religious and civil freedom, and as I noticed that the Christian religion was divided into sects, I hoped that none would dominate to the extent of becoming the state religion. » He succeeded in communicating his enthusiasm so well that Catholics were proportionally more numerous than the others to shed their blood, « to cement the work of independence. (...) Whether they were officers in the army or in the navy, or mere soldiers, they did not enlist as Catholics but as Americans, embracing the common cause », wrote Charles’ cousin, John Carroll, who would become “the father of the American Church”.

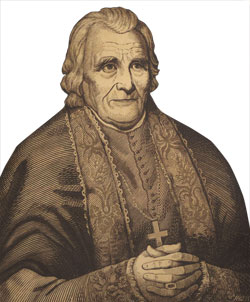

John, who was born in 1735, studied in France at the secondary school of Saint-Omer and entered the Jesuits at the age of eighteen. He was ordained a priest in 1759 and did not return to his homeland until 1774 after the suppression of the Jesuit Order. A friend of the Freemason Benjamin Franklin, he published in 1784 a report on the relations between the Church and the State in which he opted for a « general and equal tolerance ». That same year, the Holy See appointed him « head of the missions in the provinces of the new Republic of the United States of North America ». His culture, his energy, his prudence, as well as his broadness of outlook rapidly earned him the consideration of the twenty-four priests of the local clergy – almost all of whom were former Jesuits – as the undisputed head of American Catholics. He was appointed first Bishop of Baltimore by Pope Pius VI on 6 November 1789.

His brother, Daniel Carroll, was one of the two Catholics who signed the Constitution that recognises religious freedom for all « denominations », even Catholicism. Its first amendment, which was passed in 1789, could not be plainer: « Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. »

Thus, it seems that the bravery of Catholics against the English, as well as the example given by French soldiers who had come to support the Rebels, and above all that of their chaplains, broke the age-old distrust of Protestants towards the « Papists ». It is not surprising, therefore, that thereafter American Catholics did not harbour distrust for religious freedom and the separation of the Church and the State. Mgr Carroll wrote to an English friend: « I am deeply pleased to see that this policy of tolerance is beginning to be adopted in England and in Ireland. I cannot help thinking that you are indebted to America for this blessing. » At that time, it was not a question of renouncing to preach the one Truth, as the extraordinary apostolate of the French Bishops of America will bear witness.

A NASCENT CHURCH ENTRUSTED

TO THE CARE OF THE FRENCH CLERGY

The Bishop of Baltimore’s first concern was to recruit clergy in Europe. His twenty-four aging priests were actually not at all sufficient to take care of the twenty-five thousand Catholics, who were scattered among four million Protestants! Mgr Carroll suffered many disappointments in this search, since out of thirty thousand priests, who had been driven out of France by the Revolution, only about a hundred settled in the United States from 1791 to 1815; yet, providentially, they were Sulpicians or former Jesuits of eminent virtues and culture. They would engage in prodigious activity.

Their first concern focused on the Baltimore seminary. From 1800 to 1810 forty-six students registered there. and twenty-three of them would reach ordination. « The French priests, Robert Sylvain tells us, were increasingly looked on as the heads of the American Catholic community; thus bishops were naturally chosen from among their number. Like his holy friend Fr. Matignon, Fr. Cheverus, aroused sincere admiration among the most cultivated men of New England for his gentlemanly manners, his knowledge, and his virtues. He became the first bishop of Boston in 1808. Flaget, who had evangelised the West since 1792, arrived in Bardstown in 1811 after having been consecrated bishop the year before. His diocese comprised the states of Kentucky and Tennessee, and the territory situated between the Ohio, the Mississippi, and the Canadian border, where he began his apostolic voyages. The main stopovers on his trips would become the sites of future diocesan sees: Saint Louis on the Mississippi, Vincennes in Indiana, Detroit in Michigan, and Cincinnati in Ohio, Buffalo on the shore of Lake Erie. Du Bourg was appointed to the episcopal See of New Orleans in 1815; Jean Dubois to New York in 1826; Ambroise Maréchal was placed in the episcopal See of Baltimore in 1817. Finally, Bruté de Rémur would become the first bishop of Vincennes in 1834. These are the most outstanding names of a long list, for throughout the 19th century not less than thirty-five French bishops would have a place in the American hierarchy. »

Their priestly virtues as well as their extensive culture and the distinction of their manners wrought many conversions: there were 25,000 Catholics in 1790, 40,000 in 1800, and 150,000 in 1815. For example, in the diocese of Vincennes, a quarter of Mgr Bruté de Rémur’s faithful were former Protestants, who had recently converted.

One should not imagine, however, that this expansion went off smoothly.

EMERGENCE OF A NATIONAL SPIRIT

In many regions, committees formed of lay trustees who legally managed Church real estate, claimed to be able to choose their parish priest, in accordance with the practice of the Protestant communities. As their Bishops were opposed to this practice, dissensions and sometimes schisms would offer a lamentable spectacle that would considerably slow down the Church’s expansion.

Now, this revolt of laymen was often supported by a part of the Irish clergy, who were neither very cultivated nor disciplined. They had difficulty agreeing to be placed under the authority of French prelates whom they reproached for their mediocre command of the English language.

The trustees’ revolt was subdued above all by the action of Mgr John England, a virtuous and cultivated Irish priest – he is the exception that proves the rule – who in 1820 was appointed as the first bishop of Charleston in South Carolina, a region that was then on the verge of schism. He restored there the bishop’s right to scrutinise the management of parishes, but in return he instituted a consultative assembly where laymen could intervene. In this way, calm gradually spread to the other dioceses. Until his death in 1842, Mgr. England expended a zeal comparable to that of his French colleagues, but in a very different spirit. He himself worked to form an authentically American clergy, for he mistrusted both the seminarians trained in Baltimore in the « Sulpician mould » and the Irish clergy whose faults he knew. He was, in fact, the first to affirm that « the spirit of this nation is incompatible with a French administration, for one of the keenest reproaches that are made against us is that we represent a foreign and not an American Church. Now, the French will never be able to become American. »

Mgr England was evoking here a reality that is different from the cultural one, for the extraordinary fruits of the French priests’ apostolate among both the Protestants and the native populations in the West would contradict his words. Likewise he was not unaware of the fact that, before him, the French-speaking Bishops had appealed to the unity of the Church linked to the « American nation », in order to counter the excessive « community-based » claims of the Irish priests. Actually, the true opposition between Mgr England and the French-speaking bishops concerned the « Republican spirit ». The former had it out of conviction; the latter, out of necessity.

Nevertheless, Mgr England deeply marked the American Church. His influence was the decisive factor that determined the choice of bishops and contributed largely to the quality of the Irish Episcopate. Above all, however, his view of a specifically American clergy was concretised by the canonical legislation elaborated after his death by a series of provincial and then national councils, which gathered in Baltimore.

FIRST WAVE OF PERSECUTIONS

Nevertheless, the great trial of American Catholicism was its confrontation with the Protestant sects. They were very anti-papist and guided by popular evangelisers, whose religion was simple, spectacular, and emotional.

If the Church registered many conversions, it should, however, not be hidden that she had been unable to prevent the apostasy of thousands of the faithful, who were too isolated and therefore unable to resist sectarian propaganda. Now, the latter would become extremely violent from 1820, which was the date of the scission among the Protestants between the orthodox and liberal-minded. The orthodox Protestants retaliated with violent attacks not only against their dissidents but mainly against the « Romanists » or « Papists ». For them, freedom, prosperity and the marvellous wealth of America were based on orthodox Protestantism: the use of the Bible, free judgement, the observance of Sunday, strict morality were so many values that had to be defended intransigently. The restoration of the Jesuits, Pius VII’s condemnation of biblical Societies, the Catholics’ emancipation in England gave rise to a multitude of anti-Catholic pamphlets.

This propaganda fell onto fertile ground, especially in New England, where the Yankees had an aversion towards the Irish, who came to swell the ranks of the Democratic party to the detriment of the Republican party. Above all the Irish formed an undemanding workforce, which provoked a decrease in salaries.

Nativism was a movement that reacted defensively and intended to protect American institutions and ideals. All of this explains how this movement was directed essentially against Catholicism, the zeal of which was becoming more visible every day. In particular, the publication of Catholic newspapers raised alarm among Protestants. It was the initiative of Mgr England, who founded the first Catholic newspaper in Charleston, in 1822. New York had its own in 1825, and Boston in 1829. These newspapers conducted intense controversies against Protestants and did everything possible to make the expansion of Catholicism spectacular.

The Protestants counter-attacked with well-orchestrated press campaigns, which were the first of a long series. « They began to report almost daily the arrival of ships in the harbours and the number of immigrants who disembarked. Some people took the Irish for disguised Jesuits; others believed that Rome was sending a great number of poor people and criminals to the shores of America in order to weaken the Republic with a view to a possible conquest! Under the influence of these mad terrors, Native American Associations were set up in New York, New Orleans, Cincinnati, and in other places; their main goal was to exert pressure on the government. »

In 1834, scenes of incredible violence took place in Boston, the capital of American Puritanism. During the night of 11 August, a crowd that was roused by the sectarian preaching of Lyman Beecher, the father of the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, took by storm and set fire to the thriving boarding school of the Ursulines, where numerous honourable Protestant families sent their daughters for their education. For almost four years, acts of violence against Catholics were a common practice as well as arson perpetrated against churches. Appalling libellous pamphlets were widespread amongst the population, which is known to be credulous for completely implausible facts.

The bishops showed much courage. At the height of the storm, some claimed the respect of their rights, according to the principle of religious freedom acknowledged by the Constitution. This was particularly the case in public schools. But these requests, as well as those of the gentle Mgr Kenrick in Philadelphia, provoked bloody riots. « Kenrick’s powerless gentleness, the historian Maynard writes, resulted in attacks on convents and churches, and in a riot in which thirteen persons were killed and fifty wounded. It was even more than a riot; it was a three-day-long battle. Two churches, the seminary, a whole row of Irish houses were burnt to the ground, while the firemen and policemen remained passive (...); the rioters even went to find two canons and shot at the door of Saint Philip Neri church. »

In New York, Mgr John Hughes’ attitude was more effective. At the time of the riots in Philadelphia, he warned the mayor that he himself would protect the churches of his diocese if the administration did nothing. « So, you are afraid for your churches! » the mayor sniggered. « No, I am afraid for yours. » the intrepid bishop replied. A disciple of the Sulpician Dubois, whom he would succeed in the See of New York, Mgr Hugues was an integral, fearless Catholic above reproach! Maynard also relates that instead of dissipating the calumny concerning the pontifical plot to seize the American West that was circulating among the Nativists, he thundered from the pulpit: « The Protestants claim to have discovered a great secret. They make our region shudder from time to time by unveiling what the Pope intends to do with the Mississippi valley. They think they have made a fine discovery here! But not at all! Everyone should be aware of the fact that our mission is to convert the whole world – the inhabitants of the United States included – members of the army and of the merchant navy, the principal private Secretaries, the President of the United States... » It is hardly surprising that the diocese of New York was spared violence.

Nevertheless, the hostilities ended up dying down. The middle class was overcome with fear, and the political power refused to follow the Nativist claims to their logical consequence so as not to challenge the Constitution. Would the latter then be an efficient and protective bulwark for the Church?

IS THE AMERICAN CHURCH A MODEL FOR THE MODERN WORLD?

One could think so. The Church came through this first great confrontation with increased stature and strength. The damage was quickly repaired. In 1852, the gentle Mgr. Kenrick, who had become Metropolitan, presided over a new Council in Baltimore, the legislative results of which were remarkable. For a European observer, the Church resumed her expansion with disconcerting ease.

At Rome as in France, people could not help comparing this growth with the situation of the Church in the post-revolutionary countries of Europe. What a contrast, for example, with Louis-Philippe’s France where the State did not cease exerting overzealous and persecuting checks in particular on Catholic education. On 24 December 1845, Henry de Courcy observed in Louis Veuillot’s newspaper L’Univers: « You recently recalled that in the last six years, fifty-four new Catholic churches were erected in England, and you found in this fact the proof that the true Faith had progressed in this land. New York is just one of the twenty-one dioceses of the United States and during these same six years, fifty-eight Catholic churches were opened to worship. In New York, the number of priests increased proportionally to churches, and almost all of them come from the diocesan seminary founded in 1839. At that time, the diocese numbered only forty ecclesiastics. Today there are a hundred and nineteen. »

Basing himself on the American example, Louis Veuillot demanded freedom for the Church in France: « People cry out to us that religion needs protection and freedom would kill us. We only have to point to the young, vigorous American Church in order to reply to our false friends. » On 13 December 1845, Gregory XVI himself, an anti-liberal Pope if ever there was one, received Tsar Nicolas I and presented the American Church to him as the model to imitate, claiming the same liberties for Russian Catholics.

The infatuation of Catholics for the United States reached a summit during the months that followed the election of Pius IX. He enjoyed extraordinary popularity in the land of Washington: « He seemed to personify this trend of imprecise aspirations in which a blast of Christianity and a blast of Democracy were uniting on the eve of 1848. » The most important meeting in honour of Pius IX in the United States took place in New York, on 29 November 1847, the anniversary of the Polish revolution. « Americans, French, Irish, Italians, Spanish, English, Swiss, Belgians, etc… merged there in a common homage to Christ’s apostle and to Liberty. » Six thousand citizens from the city, with the mayor at the head, signed a letter to the Pope « as a testimony of the warm friendship of the American people for the cause that the illustrious Pontiff has so wisely defended ».

Obviously, the French liberal Catholics exulted. For example, Mgr Maret praised the American example and stated: « Religion is much more necessary in republics than in monarchies. Society will perish if the moral tie does not tighten when the political tie looses. What can be expected from a people, who are their own master, if they are not submissive to God? Complete independence from religion and integral political freedom are incompatible. If a people do not have the Faith, they must serve; but if they are free, they have to believe. » Fr de Ravignan, a renowned Jesuit who was also won over to American freedom in his treatise on The Freedom of the Church, would proclaim in 1849: « The Church has no need of the protection of men, of the mighty of this world, whether king or peoples; she only needs freedom. »

We will notice that these statements retain their topicality; hence, our study has its relevance, to recall that this euphoria did not last... At the end of 1852, the spell was broken. That year, Pius IX offered by way of friendship a marble block that was intended for Washington’s future monument. This gesture of courtesy caused fierce controversy until the excited populace threw it into the Potomac!

SECOND WAVE OF PERSECUTIONS

The restoration of the Catholic hierarchy in England by Pius IX in September 1850 provided the sects with the pretext for rekindling the confrontation with a very vigorous Catholic Church. The Protestants understood very well the issue they confronted in integral Catholicism, as this letter from one of them to the Royal family of England bears witness: « With regard to the attitude that Protestantism must adopt towards Catholicism, the worst thing, what we cannot do, is run the risk of being tolerant. Romanism, which denounces or excludes every other belief and never gives up the slightest portion of its infallibility, forces Protestantism to commit, out of love for tolerance, acts that are sometimes intolerant in fact. »

At that time, new press campaigns roused the United States. They focused on the defence of two Florentine innkeepers, Francisco and Rosa Madiai, who were said to have been sentenced to a long imprisonment for having read a Protestant bible. However much the bishops explained that the Madiais had actually been sentenced for breach of the peace, it was to no avail. There were demonstrations in all the towns of the country. The scenes of ten years earlier occurred anew. Henry de Courcy, who formerly used to praise American freedom, in consequence of this made a more realistic observation for his readers of L’Univers: « The unrest that the Protestants had been preparing for a long time and for which the affair of the Madiais was only a pretext, an unrest that is spurred on by biblical societies, is beginning to bear fruit; it rouses against Catholics passions of fanaticism that can sometimes lie dormant but never die out. »

Then came lecture tours in honour of the Hungarian revolutionary Kossuth, « a victim of Austrian repression » and especially those in honour of the Italian, Gavazzi, « a victim of French repression in the service of the Pope »; this brought the overexcitement of people’s minds to a head. A plot was fomented against Mgr. Bedini, the apostolic nuncio, who was on his way to Brazil, but charged by Pius IX with a fact-finding mission in the United States. His stay was relatively calm from June to December 1853. But on 21 December at Cincinnati , the police had to intervene in order to save him from the crowd, who set fire to the church where he was preaching. The representative of the Pope had to leave the country clandestinely, since all the ports were closely watched by the sectaries, who did not want to let him escape alive!

Professor Sylvain draws the following conclusion from this incident: « The Bedini case dissipated illusions, dampened enthusiasm. Pius IX had just bitterly experienced freedom; he could only be extremely struck by the fate that the Republic where the cult of liberty had become an axiom had reserved for his envoy: there, as in Europe, freedom degenerated too often into anarchy »; in actual fact, into persecutions.

THE SALT LOSES ITS TASTE

Unfortunately, the Irish Bishops, who at that time replaced the Francophile bishops in the United States, remained attached to the « republican spirit ». From 1845 on, the Irish immigrated in droves to the United States: more than 160,000 every year. At that rate, American Catholicism took on an Irish appearance in the space of a decade, and Rome had to take it into account. The demeanour of the Irish clergy had markedly improved, but their attachment to the modus vivendi that had been agreed to with the authorities and the other « denominations » weakened the Church’s apostolic zeal.

Statistics concealed the evil: in fact, when Ozanam, for example, exclaimed: « However prodigious the development of the United States had been, one has every right to conclude that the conquests of the Faith advanced even more rapidly, since the progress of Catholicism is twenty times greater than the general increase of the population », he did not notice that this extraordinary growth was explained by the influx of Catholic immigrants alone. On the contrary, the flow of conversions from Protestantism considerably slowed. The Irish, who were firmly attached to the Catholic Faith for themselves, were generally less concerned about the apostolate and were quite content with a system of religious freedom that left everyone in peace.

It is certainly one of the reasons for the little interest that the Church took in the Black population. In 1850, only 3 % of the three million seven hundred thousand slaves, – they were descendants of émigrés from Santo Domingo – were Catholic. Fifty years later, they would be no more than 2.2 %, and the American clergy would include only five black priests. The marvellous missionary apostolate of the French clergy among the native populations experienced the same sad result. Despite the conversion in droves of these people, the missionaries, who were left to themselves, had no means to counter the extermination of the most Catholic tribes, like the Cheyenne, or to their confinement on reservations. On some of them, because of religious freedom, the priests were even compelled by the federal administration to hand over their place to pastors so that there would be the same number of pastors as priests accredited to these tribes who were, however, predominantly Catholic!

Thus, on the eve of the American civil war, the situation of Catholicism in the United States was not as flourishing as statistics would make it believe. Religious freedom had indeed given a legal status to the Church, but it also enabled her enemies to prosper. Above all it distorted the Catholic spirit of a great part of the clergy: once the principle of religious freedom was admitted, it followed that a certain modus vivendi would be accepted and that the apostolate would be restrained so as not to breach public peace. In the final analysis, the separation of the Church and the State bound the Church to the State and to the other denominations. If a press campaign or a persecution arose, or if iniquitous laws were promulgated, the Church would be powerless to resist, out of fear of disturbing public order and of challenging a climate that was generally favourable. In the middle of the 19th century, most of the bishops therefore focused their zeal on the existing flock, the immigration of which ensured continual growth.

In 1860 only a few perspicacious minds foresaw that such an attitude could but condemn Catholicism to a slow asphyxia. Apostasies increased proportionally to the integration of the Irish community into Anglo-Protestant society.

Yet, the American Civil War took place and reopened the debate.