The Catholic Church in the United States

III. « Who benefits from religious freedom? »

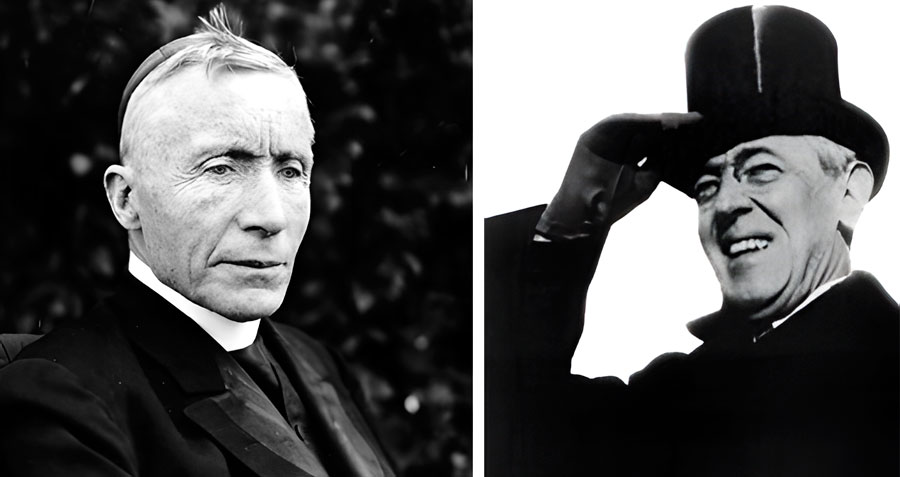

(1865-1921)

IN the hope of assuring religious peace in his country, but also out of sincere admiration for American values based on the cult of liberty, Mgr Gibbons, the Cardinal Archbishop of Baltimore, resolutely engaged the Church in the United States in a policy of unconditional support for American institutions. Persuaded that the “European model” was obsolete and that the democratic regime as invented by the United States was the way of the future, he considered that the fate of the Catholic religion was bound to it. Therefore, it was necessary to accept American-style democracy loyally and to give proof of it. In particular, the Church had to admit the separation of the state and religion as a sine qua non condition of the durability of democratic institutions. Thus, she had to set an example of respect for religious freedom, of constant dialogue with the other religious “denominations”, and of struggle against intolerance.

Once these conditions were respected, Mgr Gibbons was convinced that under such a regime, « the Catholic Church could but open out like a rose ». Yet, on three occasions, this certitude should have been shaken.

THE SCHOOL QUESTION

The first occasion was the school question in 1884. In its concern to adapt itself to American reality, the third Council of Baltimore refused to condemn public education even remotely. It decreed, however, a series of measures in order to facilitate the development of private parochial education; it called for optional religious education in public schools in addition to the compulsory syllabus. We should also know that at that time, parochial primary schools gave quality education and attracted children from Protestant families. Thanks to the development of religious communities, secondary education, in turn, began to extend, and Mgr Gibbons prepared to found the Catholic University of Washington, which would be done in 1889.

American bishops were thus setting up a remarkable school network capable of welcoming all Catholic children. It also promised to be a good instrument of apostolate towards our separated brethren.

Nevertheless, the operational costs of these schools represented great expenses for dioceses and families; these families were not exempt from local taxes, a large part of which financed public schools. The development of private Catholic education was, therefore, in the near future to lead the episcopate to approach authorities to obtain either a partial exemption from the fiscal burden or partial allocation of these resources to Catholic schools.

For the first time since the persecutions in the 1850s, the regime of the separation of Church and State sought an adjustment in favour of the Church, and thus risked a confrontation. This perspective did not fill with enthusiasm the bishops who were most infatuated with American institutions. All the more was it so because some of them like the very liberal Mgr Ireland would have preferred that Catholic children not be brought up apart from other Americans.

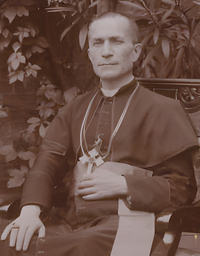

Archbishop of Saint Paul

Therefore, shortly after the Council of Baltimore, under the pretext of rapidly finding an adequate solution to urgent, local financial problems, the enterprising Archbishop of Saint Paul proposed an original agreement to the leaders of public schools in his diocese. It was nothing less than establishing a single school system, which would be financed through school taxes levied on the whole population. All schools, whether public or Catholic, would thus follow the same school syllabus; Catholic schools with their religious personnel would thus impart neutral teaching. On the other hand, all schools would offer religious teaching – after school hours – that would be compulsory for Catholics and optional for others.

In the eyes of Mgr Ireland, the advantages of this system were numerous. Catholic parents could – without having to pay anything more than their taxes – in good conscience send their children to public schools, since religious education was also given there. For its part, the diocese was relieved of a heavy financial weight. As for the authorities, they were free again to organise and supervise profane teaching as they liked.

Bishop of Rochester

Some bishops were not deceived by this and protested against this abandonment of Catholic teaching in favour of neutral teaching. They pointed out its considerable danger for souls; Mgr McQuaid and Mgr Corrigan of New York informed Rome concerning their complete disapproval. But the Archbishop of Baltimore defended Mgr Ireland by speaking in favour of his good intentions and of the financial necessities. A moral theology professor at the Catholic University of Washington, an institution that Mgr Gibbons held dear, added fuel to the fire by publishing an opuscule in which he maintained that the State’s right to supervise education was broader than what Catholics were generally ready to admit.

The debate was growing more bitter; Mgr Satolli, the newly arrived Apostolic Delegate, entered the scene in order to resolve the conflict. He did so by means of a diplomatic statement in the very style of Leo XIII, that is to say, by recalling Catholic doctrine while justifying the exception: « Far from condemning or treating public schools with indifference, the Catholic Church in general and the Holy See in particular, wish rather that, through combined action of civil and ecclesiastical authorities, public schools may exist in every state in order to dispense instruction in useful arts and natural science; but the Catholic Church disapproves of the kinds of schools that counter the truths of Christianity and of moral doctrine. Since, in the very interest of society, these unpleasant characteristics can be removed, it is necessary that not only the bishops but citizens make every effort to get rid of them in virtue of their rights and for moral reasons. »

This statement was tantamount to giving full recognition in veiled terms to Mgr Ireland, who was contributing to removing the “unpleasant characteristics” of public teaching by obtaining that public schools agree to after-school religious instruction!

For this reason, the poorest bishops or those who did not yet have a very developed school system in their diocese, imitated the example of the Archbishop of Saint Paul and, in accordance with local circumstances, came to an agreement with public authorities.

As for Mgr McQuaid, he carried on with the struggle… against the Pope. He wrote to his colleague in New York: « Here we are in a right fix thanks to Leo XIII and to his Delegate. Just when our forty years of arduous efforts were beginning to bear abundant fruit, they came and arbitrarily destroyed everything! If an enemy had done it! »

Finally, the tenacious bishop of Rochester won his claim… in 1893, when Leo XIII wrote Mgr Gibbons a letter in order to urge him to respect firmly the decrees of the Third Council of Baltimore in favour of parochial schools. But it was too late. Since the bishops had already entered into agreements with the authorities, it was impossible for the episcopate to establish a common stance in order to insist that private Catholic schools be financed by school taxes.

The Church of the United States had just missed an opportunity to complete a fully Catholic school system. The historian Maynard, who does not, for all that, conceal his sympathy for Gibbons, has the honesty to note that this direction was fraught with consequences. Although the American Catholic school system was the world’s largest, it provided schooling to only half of the Catholic youth. The other half received a strictly secular education, which means that they grew up in a Godless world. Maynard sees in this one of the causes of the moral confusion that has gradually swept through the Church, especially shortly after World War II.

AMERICAN IMPERIALISM

The rise of American imperialism should have shaken Mgr Gibbons’ ardour for American institutions even more than the school question, since consequences were disastrous for the Church, contrary to what he had expected.

We recall that in 1887, when he was elevated to the rank of Cardinal, he delivered an important and very laudatory discourse in favour of his homeland, stressing in particular the pacifism of this nation. Less than ten years later, the United States embarked on a policy of bellicose expansionism. The – Catholic! – Spanish colonial empire was the first to bear the cost. The Archbishop of Baltimore did not approve of this policy, which ran counter to his ideal conception of America. In the Cuba affair, he vainly called Catholics and his compatriots to restraint. From the pulpit, he had the courage to defend Spain against the imperialists’ slanderous propaganda.

In a detailed study of Blessed Mary of the Divine Heart’s life, the Abbé de Nantes established that, through her agency, the Sacred Heart let Leo XIII know that he had to take a stand in favour of Catholic Spain against the Protestant United States. But the Pope preferred to try to negotiate an agreement; Americans saw in this attitude an attempt at meddling that went counter to the separation of Church and State. Mgr Gibbons understood his compatriots and, once war was declared, rallied American Catholics to the Government.

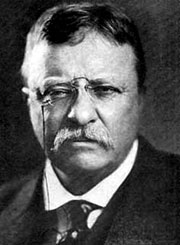

After Cuba, the United States had designs on the Philippines. When President McKinley asked the Cardinal for his opinion on their annexation, the latter answered: « Mr. President, it would be a good thing for the Catholic Church, but I fear it would be quite bad for the United States ». This was because he was persuaded that such expansionism betrayed the democratic ideal but that the « Catholic religion was more in security beneath the American flag than anywhere else ».

Obviously, the President did not heed Mgr Gibbon’s advice, and the American Army seized the archipelago. By establishing there the separation of Church and State, the new government deprived Spanish Catholic works of all resources. Their missionaries, who had made this archipelago into the only Catholic nation of the Far East, were thus forced to leave the country. In a few months, the Philippines were deprived of their clergy, with the exception of a few Jesuits and some American priests, while an influx of Protestant missionaries was arriving. Catholic schools, which safeguarded the Faith and the standard of which was markedly higher than what the anticolonialist propaganda had insinuated, were replaced with a secular school system.

In a few years, Catholic works were ruined…; the archipelago would have to wait a half century until it received once again missionaries who were sufficient in number!

However, the American government was generous and wanted to give the religious communities compensation for the despoilment of their real estate, which it valued at seven million dollars. It proposed the agreement to Mgr Gibbons, and Leo XIII approved it. Yes indeed, the Church was in security beneath the American flag…

AMERICANISM

Cardinal Gibbons was blind to the anti-Catholic attitude of the American government as well as to the consequences, in the very bosom of the Church, of his praise of a political system that was founded on the exaltation of liberty and individualism. It was the affair of Americanism that revealed it.

The publication in 1891 of the biography of Fr Isaac Hecker, who had died three months earlier – his preaching had been a decisive factor that determined young James Gibbons’ vocation – led to the crisis.

After an extraordinary career, this reader of Kant converted and entered the Redemptorists. Following disagreements with his superiors, he was driven out of his Order and founded his own congregation, the Paulists, who were devoted to the conversion of Protestants. Although the community had never included more than a hundred or so members, it had considerable influence in the United States through its publications, which spread a new spirit, the spirit of its founder.

In fact, he considered that the apostolate had to take each nation’s personality into account, since it had developed in accordance with God’s will. Thus, in his eyes, « the Americans’ independent and free character was a grace of God. »

By dint of this, he advocated new methods to evangelise America. These methods were based especially on natural virtues, which are more important for an American than supernatural virtues, and particularly on the action of the Holy Spirit in the individual soul, to which he attached more importance than to the institutional Church and the Sacraments.

As soon as his biography came out in France, there was an outcry. Fr Maignen denounced the book to Rome while the liberals defended it. They called Leo XIII to come to their rescue and intervene. But, considering the gravity of the theories for which Hecker was blamed, the Pope was forced to publish the encyclical « Testem Benevolentiae » (22 July 1899). Strictly speaking, it did not define the heresy that would be called Americanism, but it condemned five errors that can be summed up this way: « spiritual direction is less necessary in our days, since in an era of liberty, the Holy Spirit is guiding each soul individually. A second error was to put natural virtues far above supernatural virtues under the strange pretext that they were more modern and virile. A third error consisted in emphasising active virtues to the exclusion of humility, charity, and obedience. A fourth error was to reject religious vows, which restricted individual freedom and were useless to society. The fifth error was to claim that some Catholic truths had to be adapted so as to please those who would like to convert. »

Gibbons and other American bishops defended Hecker’s good name and claimed that Europeans who did not understand anything about the situation in the United States mistakenly attributed erroneous doctrines to him. They also energetically denied – even the very liberal Ireland – having supported the doctrines that had been condemned.

It seems, in fact, that they did not agree with these errors in their excessive form, and certainly not the Archbishop of Baltimore. Nevertheless, if we are to believe other bishops, in particular Mgr McQuaid and especially Mgr Corrigan of New York, Leo XIII’s encyclical was a salutary act, for Americanism was a real danger that was already poisoning the American Church.

Yet, Cardinal Gibbons used the great influence he had with Leo XIII to obtain the reinstatement of the director of Rome’s American college and of other prelates who had been penalised for their Americanism. On his recommendation, they received diocesan sees.

This clemency of Baltimore’s Archbishop is understandable. Fr Hecker’s theories were actually only the logical, albeit excessive, consequence of the exaltation of the “American spirit” that was so close to the Cardinal’s heart. If a new world was being born, making Catholic order and doctrine of the European Christianity of the past obsolete to the advantage of the American ideal, there was, in fact, no reason for this American ideal not to be introduced also within the Church and to alter certain behaviours.

From the end of the 19th century on, the Americanisation of the Church, that is to say her opening to the values of liberty and individualism, would always be the great temptation of Catholic Americans before becoming that of the whole Church after the Second Vatican Council.

Historians, however, observe that, under Gibbons’ authority, these errors were checked in seminaries and Catholic schools. Leo XIII's encyclical had indeed the beneficial effect of reinforcing episcopal control over Catholic education and publications. By that very fact, if the American Church always remained susceptible to the siren call of Liberty, she closed her heart, at least at that time, to Modernism, the poison that was fast spreading throughout Europe at the end of Leo XIII’s pontificate.

UNDER THE PONTIFICATE OF ST PIUS X

According to American biographers, this was perhaps one of the causes of the mutual esteem that would arise between Pope Pius X and Cardinal Gibbons. The latter was one of his major electors in the conclave. Saddened by the partisan struggles that political interests were stirring up and that divided Cardinals, the Archbishop of Baltimore had been impressed by the independence of the Patriarch of Venice. When he heard the latter say that « Europeans sometimes have a regrettable tendency to underestimate their brethren from other continents. A new vigour is arising and will not leave human feeling indifferent », he wrote in his diary: « This is a man of great vision; he is the one whom God wants ».

When the outcome of the vote became clearer and Cardinal Sarto was racked by the most terrible agony, Cardinal Gibbons went to comfort him in his room and managed to persuade him to accept his election.

Nevertheless, Allan Sinclair Will’s biography remains strangely silent about Cardinal Gibbons’ activity during the eleven-year-long pontificate of Pius X. He finds nothing to report except some interventions in social matters and the ceremonies, which he describes at great length, of the silver jubilee of his cardinalate and the golden jubilee of his priesthood in 1911, for which twenty thousand people gathered at Baltimore. Nothing more?

Still, we are told that Mgr Gibbons had noticed that Pius X’s standpoint was that of a man of the Church rather than that of a statesman. Now, looked at from that new viewpoint – Mgr Gibbons having enjoyed nothing but Leo XIII’s praises and congratulations – the results for the Church in America were less satisfactory than appearances showed.

St Pius X certainly showed himself more preoccupied than his predecessor when he heard conservative bishops expressing distress over the numerous acts of apostasy that afflicted the American Church but that the more progressivist part of the episcopate minimised. In fact, the number of conversions from Protestantism was insignificant, and only a strong Catholic immigration explained the prodigious growth of the number of Catholics in the United States. Yet, in the last quarter of the 19th century, 20 to 40 % of Catholics – the percentage varies according to nationalities and regions – apostatised!

The strange silence of Mgr Gibbons’ biographers, who are too inclined to praise his modernity and his open-mindedness, thus conceals the fact that their hero probably rectified his ideas under St Pius X’s influence, even though he kept intact his infatuation for the institutions of his homeland. Historians observe, in fact, that St Pius X’s instructions were carried out to the letter and zealously in the United States.

As early as 1904, the Cardinal worried about the spread of Socialism and, moreover, successfully mobilised the Church to preserve his homeland from it. At his instigation, the American episcopate supported the bishops of France, who were facing anticlerical persecution, while the exiled French communities were benevolently welcomed in America. The Cardinal also intervened with his government in the hope of putting diplomatic pressure on Paris.

Decrees against Modernism were zealously implemented. Even as academic institutions were just emerging from a distressing mediocrity, some prestigious professors were nevertheless banished from their post, and three of them left the Church.

It was also under Pius X’s pontificate that the immigration question was definitely settled: the government abandoned brutal assimilation of immigrants, and organisations were gradually set up in order to facilitate their progressive integration into American society. The name that evokes this charitable, specifically Catholic attitude is St. Frances Cabrini (1850-1917), who devoted herself to Italian immigrants.

There was no reluctance to implement either the reform of sacred music or the decrees on the Communion of children and on frequent Communion. From this followed a renewal of liturgical and religious life that would bear fruit in the following decade, by reviving a true wave of conversion from Protestantism.

THE CHURCH POWERLESS IN THE FACE OF THE FREE STATE

Above all, American bishops encouraged the zeal of laymen to develop a great number of works, most of which were at the parish level. These works were to benefit their brethren in the faith and to help the countless needy to whom American capitalism was giving birth. These works, which were carried out in the same spirit as that of Catholic Action as it had been conceived by the former Patriarch of Venice, could have had political impact. But Cardinal Gibbons countered it out of respect for the principle of separation of Church and State.

This explains why the United States adopted an increasingly expansionist, anti-Catholic policy. The Church who was, however, the very largest religious denomination, was unable to have the slightest influence! Admittedly Catholics formed the main body of the Democrat Party, but they had never defended a political line that was dictated by their faith or imposed by the instructions of the hierarchy.

Whatever their political party, presidents, except for Wilson, made a point of honouring the venerated Archbishop of Baltimore with their friendship and listening to his remarks, but they only heeded them when they agreed with their own views. This harmony concealed to the eyes of the prelate the total emancipation of the American State from Christ’s sovereignty; which is, however, the ineluctable consequence of the separation of Church and State, which had become a quasi-dogma for the American Church. Being sovereign, the American State turned into a soft totalitarianism that was certainly different from the one that would take hold in Russia, but that was just as much against the kingship of Christ: it was the totalitarianism of international high finance, which supported Freemasonry’s undertakings and worked from that time on to implement a new international order.

Catholicism and patriotism, however, always went hand in hand. After 2 April 1917, the date of the United States’ entry into the war on the side of France and England, Catholics formed the quarter of the strength of the American army and half of the navy, while they only represented a sixth of the population! Not only were they more patriotic than the others, but they also were the healthiest part of the population.

In order to assist soldiers and their families, and to see to the reintegration of the wounded and the demobilised, the Church would prove her remarkable organisational capacity. At the Cardinal’s instigation, the Catholic National War Committee was created. On that occasion, for the first time, the Bishops agreed to delegate a part of their prerogatives in their dioceses to a Committee of bishops that organised the work in the whole country, using the network of parishes. Thus they brought in sums of money that were considerable for that time.

After the armistice, the Committee turned into a Catholic National welfare Committee, which was actually the first national social organisation not dependent on the State. This experience was a false start, since once again the episcopate was afraid of antagonising the State and of infringing on the sacrosanct separation. The habit, however, of gathering bishops on a national basis endured, and so, long before the Second Vatican Council, the United States was the first country to endow itself with a national Conference of Bishops.

UNIVERSAL ESTEEM FOR THE CARDINAL

After the war, Cardinal Gibbons felt his strength progressively failing him. Since his golden jubilee in 1911, Catholics and civil authorities missed no opportunity to show attachment to and respect for him.

These festivities always led to speeches on the subject that President Taft had already developed in 1911: « We like to admire in him his tireless devotion to his country and to the Church. One of the dogmas of this Church is respect for established authority. We have always found Cardinal Gibbons on the side of law and order; he has always defended the cause of peace, brotherhood, and religious tolerance; he has always affirmed that freedom is the best safeguard of religion’s prosperity. (…) Despite the high religious responsibilities of his charge, he took an active part in all the movements that aimed at improving mankind. He has always proved himself a good Catholic not only in the religious sense of the term but in its widest secular sense. Men of all beliefs, all people, were quick to recognise in him an unselfish friend and to share the affection that his coreligionists show him. May he exercise his charge for a long time yet, may he continue for a long while to promote all human progress. Such is the fervent prayer of Catholics and Protestants, Jews and Christians. »

However, let us not delude ourselves: the esteem that Americans undeniably showed the Cardinal did not inevitably fall on the Church! In this climate of mutual respect, everyone stood his ground. As it was Protestantism and Freemasonry that held political power, it was thus they who shaped society.

The Catholic Church was still living under the watchful eye of fanatical Protestant organisations such as the American Protective Association, which was always quick to unleash media campaigns. The Ku Klux Klan would soon revive, this time no longer with an essentially racial objective but also a markedly anti-Catholic one. It does not seem that the number of Catholics apostatising noticeably decreased at the beginning of the 20th century.

Yet, it is also true that at the end of Mgr Gibbons’ life, the good effect of St Pius X’s instructions was being felt: religious congregations – even contemplative – were beginning to thrive, and the number of conversions of Protestants markedly increased.

On Wednesday of Holy Week, 24 March 1921, the Cardinal, at peace with his conscience, gently passed away in his Baltimore Archbishop’s house. His obsequies were grandiose.

In these post-war years, the United States experienced an era of prosperity that was as much to the advantage of Catholics. The American Church was entering a new stage of her history, which we will study next month. It will lead us to the Second Vatican Council and to the profound transformation that followed it.