Father Pierre Henry,

apostle of the Netjiliks

“a heart of fire amid the polar ice”

Learning of the death of Father Henry early on the morning of 5 February 1979, Father Ducharme, a veteran of the Far North, then ninety years old, declared: «If any man merits the title of saint, it is certainly him.»

Fifteen years later, as our Brother Henry of the Cross was making his perpetual vows, our Father, the Abbé de Nantes, declared:

«Father Henry is an exceptional figure, because he is a saint. Not every saint is canonised, but one day perhaps he will be found worthy of the honour of the altars. He is a saint who can be seen to enter the period of crisis and pass through it with an understanding of what was going on, all the while reacting with his whole being like an old man who cries out in torment, like an oak tree which groans on all sides but never breaks. He died faithful to the teaching of his parents, to the convictions of his mother, to his Rule, to the spirit of his community. It is very significant for us to have been able to have known, loved and possessed in our Brother Henry a witness of what has happened and of the renaissance that we are waiting to behold, the fruit of a supernatural and theological hope.»

I hope in these few pages to make you yourselves know and love him, particularly as the different stages of his life reflect the nature of his Congregation’s entire missionary effort in Canada.

THE BIRTH OF A VOCATION

Born on 16 December 1904 at Cornean, a small Breton village of around twenty families near Plouguenast, Pierre Henry knew the rough life lived by peasants, a life made easier by the Catholic faith which impregnated it. The following page written by him sixty years later provides us with the main details of his early years:

«After the grace of God, it was owing to my mother’s example and her spirit of faith that I became a missionary . She had always entertained the secret hope of having a priest among her children, and, very soon, she discovered that her Pierre would be the one. I can still see myself as a very young child following her around as she worked; she filled my heart with numerous little snippets of advice and delicate secrets. She spoke to me of prayer, of the Mass and of the examples of holy priests she had known and whom she dreamed of seeing me imitate. Her words sank quietly into my souls like the morning dew falls on cultivated ground. Oh! the sweet memories of my childhood where the unaffected conversation of my mother gradually led me into the service of God. From her soul, united to God, prayer arose quite spontaneously, like the freshness of a spring morning. Her joy delighted me and made me desire to quietly repeat the many ejaculatory prayers of her own invention which she used to say out loud as she worked.

«It was she who taught me to pray when I was very young, in the same way that birds teach their young how to fly and to sing – a precious habit which was to go on developing and to serve me so well in life! In the school of my Mama who loved to visit the sick, to feed the poor, to comfort the afflicted and to bury the dead, love and tenderness for those in need went on growing in my heart, finally leading to the irresistible impulse which would make me carry the Gospel to the most disinherited people in the world. It was owing to her that I became a missionary.»

It was in 1921, when he was seventeen, that he entered the college of the Oblates, and then in 1924 the novitiate. The assessment of his novice master, Father Alazard, was not particularly laudatory: «A somewhat obstinate Breton who loves his vocation. A mediocre candidate, good for the foreign missions.» It was this kind of reasoning that the gentle Mgr Charlebois could not help criticising, for, according to him, the missions required on the contrary the very best candidates. But fortunately, in the present case, the assessment was completely erroneous, as the superiors of the theological college soon came to realise.

Brother Henry was unanimously accepted for perpetual vows: «He no longer merits the judgement of his novice master. He is a good candidate.» On 1 November 1929, he took up his cross as an Oblate with a matchless joy. After his traditional thomist clerical formation, to which he adhered with all his intelligence and with all his heart – there was not the shadow of a doubt or a question in such a soul! – he was ordained to the priesthood on 12 July 1931. One year later, according to the practice of Oblates of the time, he was assigned to the apostolic vicariate of Hudson Bay. To a friend he wrote: «Just the thought of leaving everything to follow the Divine Master into an unknown country, so stirs my heart and soul that I could die of joy.»

«For myself, having come from a large poor family and accustomed to many deprivations, saying farewell to my family was less hard than for the others. It all took place very naturally in an act of faith. My last minutes at home, with papa and mama, on our knees on the bare ground before the fireplace, were occupied in consecrating to the Sacred Heart the two dear beings who had given me life. A peace and a profound silence enwrapped all three of us. Once the ceremony was complete, we rose and we embraced each other one last time, then I departed immediately, on foot by the orchard at the back.»

After an eventful crossing, he disembarked at Quebec where he spent a few days with Father Lelièvre who literally fascinated him. Between the celebrated preacher of the Gospel and the Sacred Heart to the Quebecan crowds, and the young missionary on his way to the polar icecap, an undying friendship was forged from that very moment, a friendship which would be a regular source of financial aid to the Arctic missions.

Taking the railway via Montreal and Winnipeg, Father Henry reached Hudson Bay in the autumn of 1932. Providentially, a longer stop than intended at Le Pas made it possible for the young Oblate to visit the bishop’s house where happily Mgr Charlebois was at home, something unusual for the wandering bishop. Father Henry would come to regard his conversation with the venerable missionary that evening as one of the greatest graces of his life. After his death, he had a devotion for him which rivalled that which he bore for Saint Theresa of the Child Jesus, which says it all!

INITIATION INTO THE MISSIONARY LIFE

Having arrived at Churchill too late to take the boat that would have taken him on to the north side of Hudson Bay, our young impatient missionary stopped there and spent his first Canadian winter with Mgr Turquetil whose enthralling accounts he listened to avidly. He spent his spare time acquainting himself with the Eskimo language. Finally, in March 1933, he was able to go north by land, using a dog sleigh. It was his first great voyage, through temperatures which dropped below 40°. At the Saint Theresa Mission in Cape Eskimo, he said his first Mass on mission, not without some astonishment: naked children ran freely down the aisle, mothers breastfed their babies, old women blew their noses noisily or spat without decorum into a can, and there was always someone leaving to relieve themselves!

Continuing on his journey, he arrived in time at Chesterfield where he had the honour of singing the Easter High Mass and witnessing the departure of Father Clabaut who was setting off to found the mission of Our Lady of the Snows in Repulse Bay, in the polar circle. While he was waiting for instructions from his bishop, he attended to the hospital nuns, and on 18 June, brimming with enthusiasm, he took part in the first Corpus Christi procession to be organised in such a latitude.

At the end of the summer, he received orders to go and join Father Clabaut in Repulse Bay. There he learned a great deal, particularly everything a missionary needs to know in order to survive under such impossible conditions. He also perfected a technique for building dwellings made of stones cemented with clay, more economical and more impenetrable to the icy wind than wooden huts. Nevertheless, he champed at the bit, as his superior did not give him any opportunity to exercise his ministry. In this his first post, he revealed the quality of his religious soul, deeply attached to the exact practice of the Rule whose apostolic fruitfulness Mgr Charlebois had indicated to him.

Father Clabaut, an excellent missionary and subsequently Mgr Turquetil’s bishop coadjutor, would himself have preferred a little more latitude in the Rule. He notes in the mission codex:

«My God, sometimes the saints manage things in a way that is difficult for those who are not saints.»

It was during this winter of 1933 that Father Henry started to feel a particular attraction for the evangelisation of the Netjiliks who lived in an even more remote region, to the north-west of Repulse Bay, in the direction of the magnetic pole. With a reputation for cruelty, these Eskimos had not yet been evangelised, even though some of them had ventured as far as Our-Lady-of-the-Snows. Father Clabaut apparently refused to let his young companion leave on so perilous a mission. With a tenacity characteristic of the proverbial Breton, Father Henry often returned to the attack with his superior, but always in vain. Then, he started to ask Our Lady for this grace, through the intercession of Mgr Charlebois, who had died eighteen months earlier.

In January 1935, while Father Clabaut was on his rounds, he met a group of Netjiliks who had allowed themselves to be evangelised and were asking to be baptised. He saw in this a sign from heaven, and he decided that on his return to Repulse Bay he would to open this new apostolic field to the ardent zeal of Father Henry. Little did he suspect, at that very moment, that the latter had nearly been asphyxiated: the cold was so intense that night in Repulse Bay that ice had blocked the chimney.

THE APOSTLE OF THE NETJILIKS

It was on 26 April 1935 that he left, not without emotion, having received Father Clabaut’s blessing. An old hand who was visiting, Father Bazin, warned him in all charity: «You have no idea what awaits you.» It was only too true! Fifteen years later, he would recount his adventures; the sobriety of style does not manage however to disguise the heroism and zeal of our young missionary. Read on:

«Once the first encampment was reached, I introduced myself by crawling under the entrance of the igloo pointed out to me. At first it was complete darkness; then as my pupils gradually dilated, I saw two old Eskimos squatting in a corner and, in the middle of the place, pieces of seal streaked with blood. I went up to the old man and shook his hand. His silence chilled me. The old woman showed herself more welcoming. “Ah! you have arrived.” she said. That made me feel better. We spent the evening in silence, for I had great difficulty understanding them. I was hungry and hoped that they would offer me something to eat. How could I open any of my cans before them without offering them some? And so, there was nothing left for me to do. I went to bed without supper. The next day, I celebrated my first Mass in this pagan igloo. They watched me without saying anything. This time necessity made me open up my box of provisions for I could not go on any longer. The old man finally ventured to open his mouth and ask me why I had come to this land. “I have come to announce Heaven.” – “You will be very hungry”, was his only reply.

«We had to walk for a total of thirty-seven days before reaching Pelly Bay. At this second departure, my guide hinted that my luggage was too heavy for his dogs. “You would do better to return”, he told me. And I felt that he wanted me to go back. On the way, he returned to the attack and said to me: “Besides, you cannot live like us because you cannot eat what is rotten.” – “Yes, I can.” Taking a knife, I cut a piece of seal killed a year ago and intended for the dogs. I ate it by dint of thinking of something else, and it went down. My companions were amazed; there was complete silence, not a smile, not a word of congratulation. But I had taken up the challenge and the matter would not be raised again.

«A few days later, I was offered raw fish, and curiously this sticky viscous flesh made me heave, and I spat it out in the snow whilst looking at the sun. But fortunately no one observed me. “As he eats what is rotten”, they reasoned, “he will be able to eat what is fresh.” Since then, I have accustomed myself to this diet, and it is only seldom that I eat cooked food. It is all to the good of my health.»

Let us pass quickly over the other incidents of this journey and over the first days in Pelly Bay where he founded the Saint Peter Mission. There, on his own and in suffering and hardship, he built a chapel, twenty feet by five, with native materials, stones cemented with clay. On 15 August 1935, the carcass work was finished.

«I made an altar with a wooden box; it was poorer than Bethlehem. I slept right next to the tabernacle, like a dog lying at his master’s feet. But my spirits had risen, I felt happy. These were the most beautiful moments of my apostolate. When I think on this today, I say to myself: those were the most perfect years of my life; if I had taken greater advantage of them, I could have become a great saint.

«At first the Eskimos kept their distance, uncertain what to think of this newcomer, this missionary whom their tribe had requested. One of the first to come and see me was the witch doctor, who enquired into the reason for my presence in his country. I realised that he what he wanted above all was my matches. Nevertheless, he hastened to repeat to the others what I had said to him and thus became my first assistant in the apostolate! He, the apostle of the devil, became for a moment the apostle of the Good God. “For a moment”, for alas he would turn against me later. Others approached me, and each time I wondered whether my life was in danger.

«I kept an open house, gave them food, and sang hymns to them. Having told them that I had been sent by Jesus, they concluded: “Then you must have fallen from the sky and not have a mother as we do”… I even consented to take off my shoes to prove to them that I had human feet and not the feet of a caribou, as they thought.

«In the autumn 1935, a young man asked me to hear his confession. “Everything you tell us is beautiful; would you save us? We live like dogs. Hear my confession, will you?

– Not before you have been baptised.

– I will make my confession all the same, for from now on I want to live a good life.

«A little later it was the turn of an elderly man. At Christmas, I was able to perform five adult baptisms. It was an extraordinary event and it was then that I felt the desire to build a large snow chapel with a diameter of thirty feet and capable of holding a hundred and twenty-five people. It was the cradle of Christianity in Pelly Bay; there we lived with all the enthusiasm of the early Church.»

At the end of a year, he should have returned to Repulse Bay, but an opportunity arose of going further north, to make contact with other tribes that were still pagan. Father Henry did not hesitate; he headed in the direction of the Boothia Peninsula where the magnetic pole is located and where he would soon be wanting to found a new mission. During this time, Mgr Turquetil was extremely worried and had even blamed Father Clabaut:

«You should not have let him go. He is a young Father without experience. Perhaps he is now dead; if he is still alive, he should be sent home.»

«Several months passed by before they were able to organise an expedition. One day in February 1937, when I had decided to visit several families, I had the surprise of seeing coming to meet me a number of strange men and dogs. It was Father Clabaut! Note that this was on 17 February, the great feast of the Oblates, an evident proof of the Blessed Virgin’s consideration. We embraced almost without being able to speak, then we gave our tongues free rein. But mine was tied in knots. Not having spoken a syllable of French for two years, I spoke to him half in French and half in Eskimo. I pulled myself together and finally managed to find the necessary words. We built ourselves a small igloo on the spot and spent the night there talking and exchanging news. Father Clabaut was very happy to learn that I had already baptised sixty people. “I have the power to administer Confirmation”, he said. “We will go there tomorrow”. We returned to the camp the following day, and the celebration in the igloo-chapel was unforgettable. High Mass and Confirmation with the Gloria (in mid Lent) and the Credo sung throughout by the congregation. It made my superior weep with joy.»

What explains the power and success of Father Henry’s apostolate, our Father remarks, is his fundamental humility. «It is not difficult to be a priest, one has simply to act like one’s former parish priest. This is what I did when I became parish priest of Villemaur. He himself did the same among the Eskimos. I speak advisedly: he formed a Catholic community in every respect like that which he had seen, loved and believed in his native parish, like that which he had received from his father and mother, basing himself on its indestructible convictions and virtues. We need a backbone. None of us will ever do anything great or good unless we imitate and receive as our heritage the convictions of our father and mother and, if our father and mother are not Christian, we must make a violent effort to entrust ourselves to another spiritual paternity and maternity to provide this necessary foundation. Without which, one is merely an adventurer, a patent revolutionary.»

Father Henry was not an adventurer; he was “the Church, Jesus Christ spread and communicated” unto the ends of the earth. All the Oblates shared this same conviction, firmly rooted in their missionary vocation and the condition sine qua non of its fruitfulness.

THE GOOD SHEPHERD

He extracted from Father Clabaut permission to remain two additional months in Pelly Bay before returning south. «You can see that I am well, he said to him. Let me perform the Maundy Thursday adoration with my Christians and celebrate Easter with them. So I returned to Repulse Bay in April and even went down to Chesterfield for the vicarial synod which coincided with the consecration of my superior who thus became Mgr Clabaut. This time Mgr Turquetil was keen to establish a regular mission in Pelly Bay, and he named it after my patron, Saint Peter. At the same time, he gave me a companion in the person of Father Vandevelde, who had recently arrived from Belgium.» This assistant enabled him to continue his exploration towards the magnetic pole.

Fortunately he was already back in Pelly Bay in 1939 when an Anglican minister arrived. Here is an account of the meeting drawn up by the pastor’s hierarchical superior: «Mr Turner, an Englishman from England, approached Pelly Bay. No one came out to meet him. Even the dogs were silent. Father Henry, a Frenchman from France, calmly waited for him. Dressed in his soutane, he approached Canon Turner and stopped a few paces from him. Without any preliminaries, he said to him: “If you agree not to propagate your message here and to depart without disturbing the peace or the faith of the natives, I will readily give you food for both you and your dogs.” There was in his voice, it seems, a touch of menace.» The Anglican settled there all the same, gave gifts to everyone and even offered some to the Catholic missionaries… but he obtained no results in Pelly Bay. He had more success among families who, dispersed further north, only received visits from the Oblate very episodically. Father Henry did not have too much difficulty reintegrating them into the Church; and the wolf disguised as a shepherd understood that there was nothing more for him to do than to leave with his presents!

“IT IS THE CHURCH WHICH TRAVELLED TO THE POLE.”

Once he had got rid of him, Father Henry was free to resume his missionary travels. «I had set my sights on another group of pagan Eskimos 180 miles away in the Boothia Peninsula, to whom I wanted to carry the Gospel at all costs. After six months, I wrote to Mgr Turquetil:

«“Ah! if only you could send us a little wood to build a small chapel in honour of the Blessed Virgin, here at the magnetic pole!”

«The requested wood arrived by boat from Repulse Bay in 1940, and we spent eight years transporting it to Pelly Bay, at a rate of one or two trips each winter. It only remained now to take it to its final destination. In the spring of 1948, I requisitioned five of my the best and most enthusiastic Eskimos. It was a stroke of audacity, but as the sea was the only route open to us, we had to take advantage of the remaining pack-ice, otherwise the foundation would have been delayed by another year.

«In five days and five nights we had transported this wood a distance of 180 miles, the same wood which we had spent eight years in getting to Pelly Bay. I had had the idea, at the time of our departure, of making this voyage a kind of Marian procession of the kind that I had heard was happening everywhere else. We therefore placed on the prow an image of Our Lady of Perpetual Succour, venerated by all our Christians in Pelly Bay, and we set off for the magnetic pole. Everywhere, the Eskimos came to meet us and prayed with us to the Virgin. Several wept to see the missionary leaving, thinking they had lost him for ever. Almost the whole of the voyage was carried out in silence and prayer.

«Having arrived on the southern tip of the Boothia Peninsula, we gave a wide berth to an encampment which we knew to be badly disposed towards us; but everyone looked at us from afar with telescopes and did not believe their eyes. It was the Church which was making its way up towards the magnetic pole. Having arrived one Saturday evening at Thom Bay, I immediately choose a beautiful plateau which overlooked the sea and dedicated it to Mary. “This is your dowry, my good Mother, reign here, be a beacon for the pagans who surround you.”

«We had to begin work on Monday morning. We had ardently prayed to Mary for good weather, but now, just as we were starting to work, a formidable snowstorm suddenly broke out.»

Having waited in vain for a lull, huddled up in the tent, the Father and his Eskimos decided to get down to work all the same:

«We built like Trappists, in silence and prayer. The storm raged continually. Nevertheless we tackled the framework, and the little chapel went up with great pain and hardship amid the squalls. Sometimes the wind tore the boards from our hands and they blew away like straws. I wept over this. And I allowed myself to say to the Blessed Virgin: «Really, You should help us.» But the storm only ceased on the fourth day when we had finished fixing the last board. And, to our astonishment, the chapel was beautiful and shipshape. Nevertheless I remained perplexed at the mysterious persistence of this storm despite so many prayers. I believe I found the answer in subsequent events. The fact is that, without knowing it, we had built on an historic site. This plateau had always served, from as far back as the Eskimos could remember, for annual witchcraft gatherings. It seemed to me that the devil did not want to vacate the site. Well! he has gone now. The Blessed Virgin has crushed him once again.»

You will observe once more that the Father Henry method is none other than that recommended by Our Lady, both at Lourdes and Fatima: prayer and penance. In this we can say that Father Henry was a model Oblate of Mary Immaculate.

«I went more than six months without experiencing a single consolation. The Eskimos said to me: “If you remain here, we are all leaving, for we do not want to be Catholic.” I stayed in the igloo and spent all my time in prayer. I made small sacrifices and, when I saw someone coming, I said to myself: Perhaps there is hope; and I put on a cheerful face for him. Ah! what a dreadful six months I spent there! I believe it was my Calvary. At the end, I said to myself: perhaps I should go down south to see my bishop. Perhaps he will tell me to abandon this station and to shake the dust, or rather the snow, off my feet, since there is nothing to do here. But now in June 1949, they brought me a young man of twenty years who was said to be very sick and who wished to see me:

– He wants to die with you at his side and to become a Catholic.

«Now here was something that exceeded all my expectations! I ran to see him, taking an image of Mary and the Holy Oils. I was able to baptise him in time, to administer Extreme Unction and to give him the blessing of a good death, and he passed away quietly in my arms. It was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen in my whole life as a missionary. Then I started to cry and I said: “Thank You, my God, for having made me leave my homeland, my parents, comfort, money, everything, everything, to bring me here and to give You this soul. Ah! yes, I have suffered for him, but I have opened the door of Heaven to him. Thank You, my God!” Yet I said to myself: Will the others come? Well! they did come. I was able to achieve thirteen catechumens in the first year.»

BEHIND THE FRONTLINE THE SALT LOSES ITS FLAVOUR

In 1950, for the first time in eighteen years, his bishop obliged him to return to France to see his family again, even though his parents were already dead. He used the break to visit his friends and the Carmel at Limoges where a Carmelite nun was praying and sacrificing herself particularly for his apostolate. With her he maintained a genuine spiritual friendship which was a great consolation to him, similar to that which also united him with a Grey Sister in Quebec who, in addition to her fervent prayers, contrived to send all kinds of necessities to the Eskimo families of Pelly Bay; was not her missionary brother bringing them the benefits of civilisation as well as the Gospel?

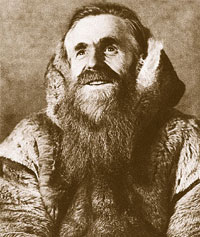

During this trip, the impact he had on those in his company and even on simple passers-by was extraordinary, as this delightful anecdote testifies: «Before returning to Canada, he visited a priest benefactor in Louisiana with whom he went out for a long walk, which obliged them to stop at a restaurant. Father Henry found himself sitting facing the street, in full view of pedestrians who were passing by. The noble bearing of the missionary, his eyes with their profound look reminiscent of the mystics of yore and especially his long, magnificent, fiery-red beard, could not fail to draw attention. People stared at him, simply stopping in the street, and then, driven by curiosity, they entered the restaurant… When the Father wanted to pay the bill, the owner refused to take his money: your presence here has attracted plenty of customers; the least I can do is offer you a free meal in return.»

But this return to civilisation also had a reverse side which for the first time plunged Father Henry into a strange feeling of sadness. His peregrinations in France as well as in Quebec and the United States, had made him aware, in a thousand small details, of how insipid the clergy had become. This disturbed him, but as yet he was unable to understand that it was the rotten fruit of the liberalism and modernism that had infiltrated the whole Church, despite the condemnations of Saint Pius X, to the exact extent that Popes Pius XI and Pius XII had refused to obey the pressing demands of Our Lady of Fatima. It would not be long now before the repercussions were even going to be felt in Pelly Bay!

THE COMBAT AGAINST PROTESTANTISM

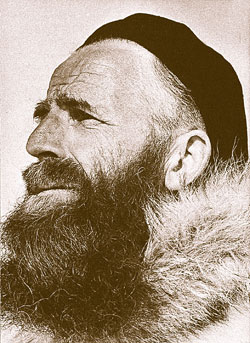

For, on his return to his dear mission on 30 April, he was pained to note the apostasy of several families, despite the dedication of his young colleague. The cause of this was the Anglican propaganda spread by the officials whom the Netjiliks met when they visited the trading posts of the Hudson’s Bay Company in Gjoa Haven or Spence Bay, two hundred miles west of Pelly Bay. Father Henry immediately understood that damage-limitation exercises were not enough to protect his mission and to win back families who had lost the faith; it was also necessary to go on the counter-attack and to found a mission at Gjoa Haven, right next to the trading station! On 28 May, he set off. The building materials had not yet reached their destination; no matter, he would do without them! As he was departing, a passing photographer immortalised his features: the face of the missionary reflects his anguish for the salvation of souls as well as his supernatural abandonment.

For, on his return to his dear mission on 30 April, he was pained to note the apostasy of several families, despite the dedication of his young colleague. The cause of this was the Anglican propaganda spread by the officials whom the Netjiliks met when they visited the trading posts of the Hudson’s Bay Company in Gjoa Haven or Spence Bay, two hundred miles west of Pelly Bay. Father Henry immediately understood that damage-limitation exercises were not enough to protect his mission and to win back families who had lost the faith; it was also necessary to go on the counter-attack and to found a mission at Gjoa Haven, right next to the trading station! On 28 May, he set off. The building materials had not yet reached their destination; no matter, he would do without them! As he was departing, a passing photographer immortalised his features: the face of the missionary reflects his anguish for the salvation of souls as well as his supernatural abandonment.

Having arrived at Gjoa Haven on 5 June, he needed to find a favourable site as quickly as possible. This weighed on his mind during the night, so much so that he was unable to sleep. So he got up, went out and walked the length and breadth of the place, reciting a great many rosaries. Suddenly, as though inspired, he planted a piece of wood in the ground; it was here that the curacy would be built which he would dedicate to the Immaculate Heart of Mary. He returned to his tent, celebrated his Mass and immediately set to work. The Eskimos looked on, but no one came to his aid. What did it matter that the manager of the Company’s trading post refused to give him heating oil for the winter? Father Henry would live like an Eskimo throughout the whole of the winter 1951-1952: he would not retreat.

In March 1952, all Inuits were summoned to Spence Bay by order of the federal government for a lung X-ray. He decided to accompany his flock. It was just as well he did, for descending from the plane, in company with the doctor, could be seen an Anglican bishop ready to immunise the population against the papists! It goes without saying that this was one of the most trying periods of his life, but nothing diminished his spirit of prayer and sacrifice, as had been the case ten years earlier at Thom Bay. This time he was not fighting against paganism but against Protestantism, maintained by the federal administration. As at Thom Bay, the power of the Rosary manifested itself in the year 1952-1953: the Eskimos came to him in such numbers that he was able to open a school. Of the one hundred and twenty inhabitants of the area, he would baptise sixty-one of them!

Obviously he was not one to rest on his laurels. Persuaded that he could now leave Gjoa Haven in the hands of a younger missionary, he hastened to Spence Bay there to found, on 23 May 1954, the Mission of Saint Michael, immediately opposite the Protestant temple. The Anglican minister sent this message to his superior: “The opposition is established in Spence Bay.” He might well have added: “and even beyond”, for Father Henry was intent on settling on King William island before them. He carried out his project in the spring of 1955 by building the Holy Cross Curacy, established on the outer borders of the two vicariates of Hudson Bay and Mackenzie.

So, in 1955, the whole Arctic had been evangelised! He wrote to his spiritual sister in Limoges: «Here the kingdom of Satan is being whittled away a little every day, but we must pay dearly for it. What an encouragement you are to me! You will only know in Heaven the good you have effected through my ministry, especially the spiritual good you have earned for my poor soul and so many other priestly souls. The little Theresa must be very pleased with you.»

Unfortunately, in that same year of 1955, the American army landed in the Arctic to construct its infamous radar stations. Opulence, wastefulness and immorality were established in the midst of the greatest poverty. How could one fight against such an offensive? The Church would have needed authority over the federal power, and this was something that Pope Leo XIII had forced her to renounce sixty years ago!

Then, without waiting for help from Rome or from the Catholics of Canada, and despite worrying symptoms of sickness and physical strain, Father Henry founded a new school to remove children from the influence of the military bases; he even turned it into a boarding school! As soon as the plan became known, an Anglican pastor was dispatched to the site; he was not short of dollars and even less so of the favour of those in government.

«I have had this minister on my doorstep for more than a month, laying the foundations of his temple and attacking Catholic teaching before our simple faithful. One fine Sunday, with a strong sense of being spiritually assisted through my dear Carmel, the idea came to me of consecrating the site of this temple to the Immaculate Heart of Mary, through the intercession of Saint Pius X. I even slipped a Miraculous Medal under the foundations of the heretical mission and, close by in the sand, another bearing the image of the saintly Pope. Imagine my surprise on 3 September, the feast of this Pope Saint, when I received an urgent call to the bedside of the Reverend. He had been laid low by an acute attack of appendicitis. He had to be evacuated as soon as possible. As a result, the Anglican mission broke down!»

Thus, while everyday life in the Far North was becoming much easier, especially as radio had reduced the distances involved and supplies could be lifted by air, the life of the missionary became more painful and the fight against the forces of Satan even more fierce. But this was merely the beginning of the drama.

GETTING TO GRIPS WITH THE DISASTROUS COUNCIL

The shock hit Father Henry in 1960. Obliged to go to Europe again, this time to Rome, to represent the brothers of his vicariate in the Congregation’s General Chapter, he came up against a new mentality which deeply disturbed him: no longer was the idea to seek to be more faithful to the spirit of the founder, but to adapt to the rule of the modern spirit! Then, having returned to his mission, in addition to the physical evils that increasingly overwhelmed him, his heart was afflicted with terrible sorrow. In May 1961, crisis struck. A severe bout of uraemia affected his mind and led to his emergency evacuation to Montreal where he would recover only slowly. What a humiliation!

After convalescing in the Benedictine Abbey of Deux Montagnes, he was staying again with his friends in Louisiana when, for the first time, he realised the significance of the conciliar revolution. He heard ecumenism and religious liberty extolled. He also learned that Pope John XXIII had received Queen Elizabeth of England, the head of that Anglican Church which had wrought so much harm among his Eskimos. Fearlessly he wrote: «Tolerance presents the illusion that all religions are good; this is a dangerous frame of mind for the true Church, the Catholic Church. The clergy is itself imbued with this false theory. How can the situation be remedied?»

As the Catholic faith cannot alter, these innovations could only be a supreme attack by the Devil against the Church. He was going to pursue the fight with the weapons that are well known to us.

Having made a full recovery, he received permission to return to the Far North, but he was not allowed to go back to the magnetic pole or even to Pelly Bay. He was entrusted the spiritual direction of the school in Chesterfield. It was then that a ten year martyrdom commenced for him! Everything was changing around him. All the new ideas were being accepted: the reform of catechetics, special methods of education. He was reduced to fighting to prevent adult films from being shown in Catholic schools: «It is not necessary to show evil to children to enlighten them and put them on their guard!» he raged.

But above all, having settled within the apostolic vicariate now become the diocese of Churchill, he took part in meetings with colleagues who wished to apply the conciliar revolution. Each time it was like a thorn pressed in his heart: no, he could not accept the Protestant Mass; no, he could not give up the soutane or the Oblate’s cross. «On his own admission, he gives the impression of being narrow-minded and out of date», writes his biographer who was in fact his Provincial at the time! And he adds: «Kayoaluk knows he is right but does not feel able to discuss the matter with his Provincial. Before him he appears to lose his mental faculties and is incapable of defending himself.»

Who can measure the Calvary of this exemplary religious and of several others since forgotten? For we are of the opinion that their missionary heroism was the fruit of their humility: they were always convinced that they were nothing without their Congregation, and that obedience was the surest means of doing God’s will. And now religious obedience seemed to be constraining them to disown the very essence of the faith. For Father Henry, it was not only a question of soutanes and rites, it was a matter of whether the Catholic faith alone opened the doors of Heaven. This is what he had been taught, this is what he believed in, and it was for this reason that he had gone to the ends of the earth to save a few hundred souls, with the manifest aid of his Immaculate Mother. And now he was being told that the Spirit blows everywhere, that Protestant pastors had to be respected, that religious liberty was a right of Man, as if one were entitled to damn oneself!

«For a month now, he wrote, I have passed through great anguish, darkness and doubt, and I have seen very little of the light of Mount Tabor. Never in my life before – he was sixty – have I felt such a strong need for a spiritual guide. There are moments when I am at a complete loss; it seems to me that the world has never been so bad and yet I am told that it has never been so good, so spiritualised, and that it is I who am lagging behind the times. However, I enjoy inner peace. I love Chesterfield and its young people, and I rely on God for whom nothing is impossible. The devil is jealous of the good which is done here despite everything.»

It must be said that he had a great reputation with the young people at the school. He acquitted himself of his role in a marvellous manner, succeeding in helping several of them stay faithful to their vocation. Unfortunately, his young people had to go south to continue their studies, far from their guardian angel. One day in 1965, he took advantage of a short trip to Montreal to go and visit his alumni at the school in Churchill; he had the impression that they were like sheep without a shepherd.

«My visit was a great occasion for them; so much the better if it did good to their souls. The better of them continue to write to me, especially those who aspire to the priesthood. They have need of great graces to remain good. They have Mass every Sunday and sometimes on Saturdays, but the organisation and the ambience of this kind of boarding school do not favour piety and virtue, and then their time is monopolised by leisure, social activities, sports, dances, etc. Oh! how I wish I were already, and ever more daily, a great saint who could save them!»

It was in this continual inner heartbreak that Father Henry spent the last ten years of his life in the Far North. As his health continued to deteriorate and he suffered more and more from the way his community was evolving, his bishop and his provincial invited him to leave the diocese of Churchill once and for all in the spring of 1971. Having first settled in Sutton, he did a little pastoral work at Sherbrooke, preaching and hearing confessions during Eucharistic retreats. In September 1973, he settled in Mauricie with the agreement of his superiors, for Father Henry, as an exemplary religious, never compromised his vow of obedience.

However, at Shawinigan, he was long solicited by Mgr Lefebvre’s Society of Saint Pius X which had opened a priory there. Our friends in the Counter-Reformation exerted themselves to counteract this influence which could have led him into schism. As an assiduous reader of the Letters to my friends and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, in November 1974 he agreed to meet our Father who remembers the occasion perfectly:

«At our first meeting, at the home of the leader of the CRC circle at Trois-Rivières, during a snowstorm that blocked us in for a whole day, we spoke of that which was torturing him: this New Mass. Certain people had told him it was invalid and, for him, it had a Protestant inspiration and character, which is what he most loathed about it! I have never celebrated this rite and nor had he, but nevertheless I did my best to demonstrate to him its certain validity and unquestionable liceity. At the end, he seemed happy to trust what I had said.»

The Bishop of Trois-Rivières, urged by our friends and moved by the service record of this old missionary, was more than happy to grant him permission to continue to celebrate Mass at Shawinigan in the traditional rite on behalf of our friends. This enabled him to continue to do a little good right till the end of his life. It was only in December 1978 that his worsening heart condition forced him to retire to the infirmary of the Oblates at Sainte-Agathe-des-Monts, where he passed away peacefully on 4 February 1979.

A short while before, he had said: «I am going to Heaven from whence I will draw you by the hand.» Let us be confident that he will do this for everyone who accompanied him and supported him during his long martyrdom. But there is something more: today, as we in our turn pray for the triumph of the Immaculate Heart of Mary and the renaissance of the Church, we can only join our prayers to those of Father Henry, Mgr Charlebois, Mgr Fallaize and Mgr Grandin, all those great Oblate missionaries today forgotten, but who so loved and served their Immaculate Queen that She could not remain deaf to their supplications. Their zeal for the salvation of souls and their indefectible love for their Congregation and the Church, are the unquestionable pledge of the rebirth of missionary zeal in the Church. They too will return with their hearts of fire and, through their faithful successors, they will evangelise the most forsaken of men. Then, according to the promise of the Most Blessed Virgin, the Reformation and liberalism will be laid low, and Christ will effectively reign «from sea to sea, from the River to the ends of the earth.» (Ps 71)

Brother Peter of the Transfiguration