SAINT CHARLES DE FOUCAULD

2. The Unbelieving Orphan

AN UNHAPPY CHILDHOOD.

THE vicomte François-Édouard de Foucauld de Pontbriand married Marie-Elizabeth de Morlet, on the 15th May 1855. They were both profoundly Catholic, as we have seen, and resolved to bring up their children according to the ideal illustrated by the virtues of so many of their forebears.

Their first son, Charles, was born in 1856, but the child died after only a few months. Fortunately, a little Charles-Eugène was born at Strasbourg on the 15th September 1858. He will be followed by Marie, born on the 13th August 1861.

« A boy and a girl ! The happiness which must have been complete in the Foucauld household then began to desert them. For inexplicable reasons, Édouard changed completely and went through periods of such deep depression that he became incapable of work and of leading a normal life. There was talk of neurasthenia, and various doctors were consulted. The round of the doctors begins and will never cease. » Elizabeth will quickly lose hope of ever seeing him cured. Édouard will enjoy periods of remission during which time he is able to return to his family. « Then he will relapse into melancholy. The crises become more and more frequent. He will sink into total despondency and will end in a state of quiet delirium, incapable of recognising the members of his family or of talking to them. » (Marguerite Castillon du Perron, Charles de Foucauld, Grasset, 1982, p. 22)

Charles, therefore, grows up away from his father. The vicomtesse and her two children move in with her father, Colonel de Morlet who, in 1842, marries a second time. His new wife is Marie-Anne Amélie de Latouche, whom Charles nicknamed “ Bonne Mémé ”.

and her two children.

« Every morning and evening Elizabeth de Foucauld took Charles’s hands, joined them and showed him how to pray. The two of them knelt down before the little altar placed on the chest of drawers in his bedroom, and, as it was the month of May, the altar was adorned with a statue of Our Lady and vases of flowers renewed daily. But that is not sufficient. God is present everywhere. He has created all things and we must ceaselessly give Him thanks. She would often take him for walks to have him discover the beauty of the world and to teach him to make the sign of the Cross before all the many crosses set up at the cross-roads. She would send him to gather violets, cowslips, buttercups and daisies and help him to form them into bouquets to be placed at the foot of the roadside shrines along the way. Together they would say their “ Hail Marys ”. They were moments of happiness for Charles and left him feeling a great peace. This peace and this sweetness, however, are not really joy. Without being able to define it, Charles senses a mystery and suffers through not knowing it. » (Castillon, p. 20)

The dominant memory the poor little orphan will keep of his mother is of a « very sad » maman. On the approach of a third birth, the vicomtesse dies of a miscarriage on the 13th March 1864, murmuring : « May God’s will be done and not ours. » She was only thirty six. Her husband, in his turn, died in the August of that same year, aged forty-four. The children were then entrusted for a few weeks to their paternal grandmother, the vicomtesse Charles-Armand de Foucauld, who had also just lost her husband. As she was taking the children back on the 6th October 1864, the vehicle was attacked by a herd of cows. Struck with terror and fearing that the children were in danger of being trampled on, she had a sudden heart attack and fell down dead beneath their eyes. So many bereavements in only a few months for children of six and three !

By way of family, all they were left with was Aunt Inès Moitessier, their father’s sister, with her two daughters, and Colonel de Morlet and his wife, who made Charles and Marie welcome. This grandfather, of whom they were very fond, was a former student of the Paris Polytechnique, a brilliant colonel and a keen archaeologist. He lived in Strasbourg and gave the children a very gentle upbringing.

This unhappy childhood is lit by a ray of light : the holidays spent at Louye with the Moitessiers, who surround the two orphans with maternal care.

THE MOITESSIERS.

Aunt Inès was very rich. She had married Sigismond Moitessier, a banker, considerably older than herself, and a widower at that. A daring, clever and powerful man, his fortune was recent. His family had gone over to the Orleanists, to Louis-Philippe “ king of the streets ”. He himself appreciated the ideas of the encyclopædists and of Rousseau.

Of a superior intelligence, an incomparable mistress of the home and accomplished woman of the world, Inès Moitessier formed, with her husband, a very united couple. She shared her husband’s modern ideas, but she was also deeply pious. They both used their power and their money to honour God and to help the poor. Charles was to be very happy with them.

Their elder daughter, Marie, was of a very keen faith and showed an astonishing fervour for her age. She was fourteen and she welcomed her orphaned cousins with great affection. She took them to Mass every morning and then to kneel before the Blessed Sacrament and the statue of the Sacred Heart.

THE HIGH-SCHOOL BOY.

On the 19th July 1870, Napoleon III declared war on Prussia. Colonel Morlet weighed up the risks of a German occupation and decided to leave Strasbourg to live at Rennes with his family. After the disaster of Sedan, they fled to Switzerland.

On the 26th February 1871, France ceded Alsace and the north of Lorraine to Germany, after which the Morlets came back to France and settled in Nancy. The Father Delsor, who undertook to help Charles catch up with the studies he had missed for a year, judged him to be « intelligent, taking an interest in his studies, of a gentle character, more girl than boy ». He is no fighter !

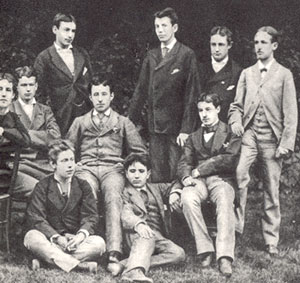

In the autumn of 1871, he starts the Lycée in class three : he is thirteen years old. On the 28th April 1872, he makes his first Holy Communion and is confirmed by Bishop Foulon in the cathedral of Nancy. Charles de Foucauld will himself say of his first Communion that it was « very pious », and made after « a long and good preparation », a Communion « surrounded with graces and the encouragement of an entire Christian family, beneath the eyes of the beings I cherished most in the world. » His cousin, Marie Moitessier, came especially from Paris for the occasion and brought him a gift, “ Les Élévations sur les Mystères ” by Bossuet. After his conversion, this will be his first reading.

Charles was happy at the Lycée ; he liked his teachers and he made friends, Gabriel Tourdes in particular, with whom he stayed in correspondence all his life. But they both lost the faith during those years of study. They certainly received a very good humanist culture but, later, Father de Foucauld would vigorously denounce the lack of philosophy and the atmosphere of immorality and incredulity of our high schools. We need to quote these all too unknown texts of his in these times when secularism is again virulently perverting our young people.

« A good, true philosophy, not just for the sake of passing exams, but for the good of one’s soul : if our dear Olivier, if I, had studied a true philosophy we would not have experienced doubt. Our doubt and that of so many others had only one cause : ignorance. We regarded difficulties that had been solved centuries ago as insoluble, but no one ever taught us that they had been solved. » (To Marie de Bondy, letter of 1st October 1897)

The poor orphan obviously had no one to talk to ; his grandfather was too old, and he was not going to find a master at the Lycée capable of answering his questions !

To his brother-in-law Raymond de Blic, he wrote on 12th December 1899 :

« How I understand your sadness at seeing the way things are going in France ! Never, dear friend, agree to sending your children to the university ! I was there, and I know what it is ! Even those teachers who are not bad – and none of mine were bad ; on the contrary, they were all very respectable – but even they do harm in that they are neutral, and young people need to be instructed not by those who are neutral, but by believing and holy souls, by men, moreover, who are learned in matters of religion and who know how to give an account of their beliefs and who can inspire in the young people a firm confidence in the truth of their faith. It would be better to do as your ancestors, who came over from England to France, and who went abroad or sent their children overseas rather than deprive them of a religious education given by priests ! Let us seek first the Kingdom of Heaven and all the rest will be given us over and above.... Apart from teachers who are nearly always neutral, rarely good, there is the milieu of detestable friends. Even the good teachers, moreover, cannot make up for religious instruction given by religious – an infinite good ! Even the good teachers will utter stupidities in philosophy, and will give vent to heresies without knowing it or meaning it ! How fortunate you are to have received a religious education with the Jesuits ! And how happy your children are to be having this good fortune ! For all the world, come what may, do not give way on this point ! »

He will even offer to have his nephews at Notre Dame des Neiges in order to save their souls :

« Mimi tells me that you are worried that the Jesuits may be expelled. I beg you, never to send your children to government high schools. The teachers do not have the faith, and the pupils are of the worst kind ; the general atmosphere is deadly for souls. If the Freemasons insist on these schools, they have good reason ! I lost the faith there, even though I was given a very pious upbringing and made a very pious First Holy Communion. Let my experience be sufficient in the family, I beg you ! If there is no Jesuit house nearby where you can send Charlot, in case the Jesuits of Dijon are expelled, you can bring him here for a few years ! He will be made to finish his classes here, piously, in our convent, and then he can do what he likes. » (To Raymond de Blic, 5th March 1901)

Plainly an unrealistic solution, but it shows to what extent lack of philosophy was the main cause of his losing the faith ! Charles de Foucauld will ceaselessly come back to that point.

« I shall begin by making a confession : your faith was only shaken ? Mine was completely dead, for years ! For twelve years, I lived without any faith at all. Nothing seemed to me to be adequately proved. The equal faith with which one follows such diverse religions seemed to me to be a condemnation of them all. And the faith of my childhood seemed less acceptable than any other, with its 1 = 3, which I could not bring myself to state. I found Islam very pleasing with its dogmatic, hierarchical and moral simplicity, but I could clearly see that it was a religion of no divine foundation and that the truth did not lie there. The philosophers all disagree with one another ; I remained twelve years denying nothing and believing nothing, despairing of the truth, not even believing in God, since no proof seemed sufficiently evident... I lived as one can live when the last spark of faith has been snuffed out. By what miracle did God’s infinite mercy bring me back from so far ? » (Lettres à Henri de Castries, Grasset, 1938, p. 94-95)

How can we not immediately emphasise the fact that the Father de Nantes has answered this expectation by creating a school of thought capable of giving an account of our reasons for belief ? Those who were his pupils, more than forty years ago, can bear witness to that. Today, everyone can judge of that by listening to the philosophy course recorded on cassettes and by reading the “ Métaphysique totale ” (French CRC 1981-1982), but also “ L’Apologétique ” (1984-1985) and the “ Morale totale ” (1985-1986). “ Total ” is the right word : a fullness of doctrine capable not only of immunising young minds against all modern errors, but of making them enter into communion with the sweet primary truth.

THE STUDENT DEBAUCHEE.

When the faith is completely lost, there is nothing left to restrain the passions. The first of these in which the young Charles will indulge is reading. Between the age of fourteen and fifteen he will read the whole of his Grandfather’s library, with no discernment. With his pocket money, he will buy 1800 books, of a disconcerting mixture. Similarly, he will give way to gluttony. Some authors, like Madame Castillon du Perron recently, will invent a psychoanalytical cause for this self-indulgence : as an adolescent he was supposedly traumatised and frustrated by the marriage of his dear cousin, Marie, celebrated in April 1874, with Olivier de Bondy, of whom he was supposed to be “ jealous ”. Our Father refutes this crude error. We shall see the role played by the very tender affection that will link him to his cousin. For the moment, she does not play a major part in his life. She is twenty-four, and he is only sixteen. Besides, he never speaks of her in his letters.

At the end of the school year 1874, he was given permission to take his Baccalauréat early and passed with the grade Assez Bien (Quite good). His Grandfather then put him down for the Sainte-Geneviève school in the rue des Postes, Paris, so that he might prepare for the military academy of Saint-Cyr. But Charles grew bored with this school ; he gave way to idleness and every kind of dissipation and aberration. He began a life of debauchery.

Some years later, he will write to Marie de Bondy on the 17th April 1892 :

« At the age of seventeen, I began my second year at the rue des Postes. I think I had never been in such a lamentable state of mind. In a certain way, I behaved more badly at other times, but then some good had grown beside the bad. At the age of seventeen, however, I was all egoism, all impiety and desire for evil ; I was as though in a state of turmoil (...). There was not a trace of faith left in my soul. »

Since he refused to work, the Jesuits expelled him a few months before the competitive exam. His Grandfather paid for him to have a tutor and, after three months, he was allowed to take the entrance exam for Saint-Cyr, coming 82nd out of 512. He enlisted on the 25th October 1876.

CCR n° 291, December 1996