SAINT CHARLES DE FOUCAULD

6. The Trappist Monastery (1890-1897)

NOTRE-DAME DES NEIGES

of Notre-Dame des Neiges.

On the 16th January he arrived at Notre-Dame des Neiges, and on the 17th he entered the community.

« What are you able to do ? Dom Martin, the Abbot, asked him, in accordance with the rule of Saint Benedict.

– Not very much, he answered.

– Can you read ?

– A little.

– And what else ?

– Sweeping. »

On the 23rd January, he received the name of Brother Marie-Albéric, after the name of the second founder of La Trappe, Saint Albéric.

«So, he sweeps, he scrubs, he polishes, he shines, he cleans; he never wastes his time. The air is very good for his lungs. They are at an altitude of 1100 metres! The monks around him, moreover, are all very fit. Beside the monastery, there is a pine forest where he often takes a walk. He thinks of all his nephews and nieces. He marked in a note book birthdays, deaths, first communions.» (Castillon. p. 197)

He is happy, and he is at peace. He discovers Saint Teresa of Avila, who will make a big mark on his spiritual life. Following her example, he will be ablaze with the same love that she had for the sacred humanity of Jesus and with the same desire to imitate Our Lord. He copies out long passages from the saint.

«But he had left without warning a soul. He was seen as an employee or a servant on the platform of a double decker, which seemed bizarre. Invitations were addressed to him, but they remained unanswered, which seemed even stranger. Duveyrier was in despair. His house at Sèvres seemed empty without the visits, which had become a habit with him. “ I am in the country, with good friends ”, Charles wrote to him at first in March, and then, as he had promised the truth, he wrote on the 24th April to complete this news by telling him of his vocation and the reasons that impelled him to become a monk:

«... “Why have I entered La Trappe? That is what your dear friendship asks of me. Through love, through pure love. Our Lord Jesus Christ lived as a poor man, working, fasting, obscure and disdained as the last worker; he spent days and nights alone in the desert. I love Our Lord Jesus Christ, though with a heart that would like to love still more and still better. But, any way, I love Him, and cannot bear to live a life other than His, a life that is sweet and honoured, when His was the hardest and most disdained that ever was... I cannot go through life in the first class whilst He Whom I love went in the last... the greatest sacrifice for me, so great that all the others do not exist by comparison and are as nothing, is the separation for ever from an adored family and from a very small number of friends, but to whom my heart is attached with all its strength: there are only four of five of these very dear friends, and you are one of the first: that is to say how much it costs me to think that I shall never see you again...» (ibid.)

It is still his pilgrimage to the Holy Land that is guiding and leading him on to... we shall see where. For the moment:

«I was expecting nothing but the Cross; I have received peace», he wrote in 1893 (Six, p. 124).

In fact, peace and spiritual consolation abounded: he says so in letters to Marie de Bondy. For example, on the 7th April 1890:

«I should not say that I bore the fasting and the cold well: I did not feel them at all. As for the Lenten diet, only one meal a day at 4 h 30, I can only say one thing: I found it pleasant and easy, and I did not feel hunger for a single day. Yet, I did not overeat.

«As for my soul, it is in absolutely the same state as when I last wrote to you; the only difference being that the good God supports me still more. He supports me in both body and soul. I have nothing to bear, he bears everything. I would be very ungrateful towards this most tender Father, towards our most gentle Lord Jesus Christ, if I did not tell you how He holds me in His hand, putting me in His peace, keeping trouble away from me and chasing away all sadness from the moment it tries to approach.

«This state is so unexpected that I can only attribute it to Him. What is this peace, this consolation? It is nothing extraordinary; it is a union of every moment, in prayer, reading, work, in everything, with Our Lord, with the Blessed Virgin and with the saints who surrounded Him in His life. The Divine Office, Holy Mass and prayer, where my dryness made everything tedious for me, are now so sweet despite the many distractions for which I am to blame. Manual labour is a consolation through resemblance with Our Lord and a continual meditation. Or rather, it should be: I am very distracted. Let us hope in the infinite mercy of Him Whose Heart you made me know...

«I am in a state that I have never experienced, except for a little on my return from Jerusalem; it is a need for recollection, for silence, to be at the feet of the good God, to look at Him almost in silence. One feels, and would like to remain almost indefinitely feeling, without even saying it, that one is all God’s and that He is all ours. Saint Teresa’s “So is it nothing to be all God’s?” keeps the prayer going.»

This peace and this consolation do not prevent the sorrows of the heart. This man, already advanced in the way of asceticism, does not miss the newspapers, the news of Paris, the entertainments, no! Only one thing pains him: separation from his spiritual Father and Mother. He suffers to know that she is suffering, for she tells him. But he elevates her thinking. He is going to begin by being a tutor for her, whilst calling himself her child. He brings her back to the supernatural:

«In this sad world, we have, after all, one happiness that neither the saints nor the angels have: that of suffering with and for our Beloved. However hard life may be, however long its sad days, however consoling the thought of this good valley of Josaphat, let us not be more eager than God wishes to leave the foot of the Cross. Good Cross, said Saint Andrew. Since our Master has deigned to make us feel, not always its sweetness, at least its beauty and its necessity for anyone who would love Him, let us not desire to be detached from it sooner than He wishes. And yet God knows that the day when this exile ends will be welcome, for there is more force in my words than in my heart.»

(Letter of the 5th February 1890, Six, p. 103)

These lines are precious pearls; expressed in a bare and simple style, the straightforwardness of the soul of this saint shows through. He admits that he does not always see the sweetness of the Cross; all the same, he understands its necessity and its beauty, and that in itself is a great thing! And he consoles himself by thinking that one is with Jesus, that one wishes to carry the Cross with Him and to stay with Him to console Him for as long as this earthly exile lasts and for as long as He wishes.

Let us note one little thing, very minor, concerning his interior sentiments rather than his external actions, but which shows even now how salutary his apprenticeship with the Trappists had been for him... On the 26th May of that year, three months after his entry into the community, he wrote:

«The origin of this dryness is nearly always in the feebleness with which I resist temptation. Especially temptations against obedience of the mind. I find it difficult to subdue my mind: that will not surprise you.»

(Letter to Marie de Bondy, 26 May 1890)

If this phrase is taken out if its living context, which we know from elsewhere, and from what follows, one could portray an indomitable Foucauld, a man consumed with his independence, who has lost none of his aristocratic and military authoritarianism and who, for seven years, dreams only of regaining his freedom. That would be a total misinterpretation. If we read what follows, we find that he is concerned, from his earliest months in the monastery, to attack, in order to destroy even in the smallest things of the conventual life, that autonomy of mind which is the basis of human disorder :

« I find it difficult to subdue my mind : that will not surprise you ! Yet, it is no little thing : I do not accept the manual labour I am given to do with sufficient joy. It is a great lack of love. If I were aware how much that brought me close to Our Lord, how happy everything would make me. May Our Lord’s will be done and not mine ! I tell Him that with all my heart. I tell Him that at least I want to tell Him with all my heart ! For I am afraid of telling Him with my lips only, and yet it is true that I only want His Will ! »

Fortunately, we have the testimony of his novice master, who observed two days after his arrival :

« The good young man has entirely divested himself of everything; I have never met such detachment, and all with an excessive modesty. He can boast of having made me weep and of having made me aware of my own wretchedness. »

(Letter from Father Eugene, novice master, 19 January 1890, quoted in Cette chère dernière place, Lettre à mes frères de la Trappe, Cerf, 1991, p. 45)

NOTRE-DAME DU SACRÉ CŒUR OF AKBÈS.

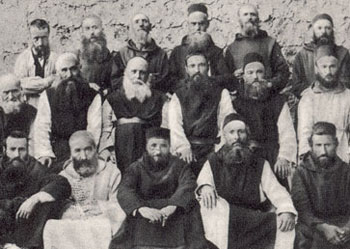

In June 1890, six months after his entry, his superiors sent him to the Trappist monastery of Cheiklé, near Akbès, as he had requested. It was a very poor monastery, «a collection of wattle and daub wooden huts, with thatched roofs, in a deserted valley».

« We are installed in quite a vast encampment. There are cattle : cows, goats, horses, donkeys - everything necessary for a big cattle farm. In our encampment, we also lodge fifteen to twenty Catholic orphans, between five and fifteen years of age. There are at least ten to fifteen lay workers, whom we also lodge; finally, there is a varying number of guests: you know that the monks are essentially hospitable [...]. Our main work is working in the fields. »

On the 15th December 1890, he wrote to Father Huvelin to express both the feelings of his grateful heart and of the peace he savours.

« Saint Teresa has taught me that it is permitted not to be detached from those we love and to desire and to miss those who do good in God’s Church... I am always impatient for news of you, but now more than ever, especially in January [...].

« These last days, I have been full of the thought that this time last year I was with you and with them. Soon 1890 will go to join the years that have passed... dear 90, whose first fifteen days are such a poignant memory for me, so full of emotion and sorrow, all the rest of which is so abundantly filled with divine graces... The year 90, in which I left so much and received so much!... received the Holy Habit, this bridegroom’s habit which Our Lord has given to such an unworthy being... received this wonderful peace in which it has pleased Him to keep me without interruption! Give thanks for me, Father, thanks for the infinite graces of those first fifteen days of January 90, so dear to my heart, so full of memories, in which you have a part, so full of God’s very goodness, so loved, so marked in the very depth of my heart, so blessed through many divine favours! Give thanks for these eleven months of religious life, where God has placed me in such an admirable state of peace that I am bound to be inspired with great gratitude, great emotion and great faith! Thank Him also for the great good that you have done to me, for the sight of the other novices obliges me to give frequent thanks for having been prepared for the life we lead... I am gathering the fruits of your preparation, and I am aware of all that I owe to your dear hand which worked on such sad soil.» (Père de Foucauld – Abbé Huvelin, p. 8-9)

For their part, his superiors and his brothers were inexhaustible in their praise of this exemplary monk.

Dom Polycarp, the founder of the Cheiklé Trappist monastery: « Brother Albéric is still the little saint whom you know and still as he was with you at Notre-Dame des Neiges. He is always edifying, always gives delight, sometimes gives cause for alarm [through he desire for penance]. Do not cease to pray often for him.» (Letter of 10th December 1890, Cette chère dernière place, p. 64).

The Prior, Dom Louis de Gonzague, is no less full of praise: « Brother Albéric’s presence among us is a great grace from the good God and a daily lesson.» (10 February 1892, ibid., p. 89)

« If we are not too unworthy of it, God will make a true saint of him.» (ibid., p. 95)

« In my greatest difficulties, it is sufficient for me to cast a glance at him in church to feel consoled.» (Letter to Dom Martin, 4 February 1892, ibid., p. 89)

« Father Marie-Albéric is always a treasure of consolation for his superiors and of edification for the community. » (Letter to Dom Martin, 18 August 1892, ibid., page 108)

FIRST VOWS.

On the 3rd February 1892, he is admitted to take his simple vows, happy to attain a more intimate union with the Spouse. For him, it is a mystical espousal with Christ, as he will write later to Father Jerome:

Through your simple vows, «you were made, three years ago, the spouse of Jesus: at every moment of your life, look for your duties in this name: to be at every moment what a spouse of Jesus should be, this sums up everything [...].

« Let us both belong to Jesus, as faithful spouses of our Unique Spouse!» (8 May 1899, ibid., p. 197-198)

There are some who will be surprised that a man should use such feminine language, he, a former officer, the heroic explorer of Morocco and such a penitent monk! But our Father has often explained to us that with the saints this manner of speaking in fact reveals the mystical richness of their soul combining the two registers: the holiness of the man who is all gift, energy and alacrity, and that of the woman who is reception, tenderness and sweetness. Brother Albéric is like that. His ardent love of Jesus leads him to such a degree of conformity with his Beloved that he desires only one thing: to descend, to become very small, humble and fragile, even to having the soul of a spouse and, with regard to Father Huvelin, to be regarded as a little child:

« I feel myself to be more than ever a little child; it seems to me that I am four years old... I see my powerlessness, my uselessness, my incapacity, my indecision, I see that I cannot take a step without you, that for everything I have to have recourse to you, that you have to hold me not only by the hand but in reins...» (3 March 1898, Père de Foucauld – Abbé Huvelin, p. 71-72)

Brother Marie-Albéric, however, does not know perfect joy for he feels a growing need to respond to the grace received in the Holy Land, by living in greater conformity with his Beloved. Furthermore, Dom Polycarp, with his experience, sees that this monk is called to an exceptional destiny. Later, Charles de Foucauld will write:

«Seven years ago, I thought I had found what I was looking for, with the Trappists; from the beginning, I saw that it was not here, but I had hoped that it might be, and that one could lead that life here. For three years, I have seen that that hope has to be abandoned... From the very first days, I never found at Notre-Dame des Neiges my ideal, and if I had not intended coming here, I would not have stayed.» (Letter to Marie de Bondy, 24 June 1896)

In 1893, they wanted him to do theology studies, and he had a feeling that they were probably going to send him to Rome for higher studies so that he could become a priest, which would lead him to be a superior, whereas he had taken a vow to live in abjection, in the last place. And he was not mistaken, for Dom Louis de Gonzague wrote to his sister Marie de Blic, two days after his simple profession of the 2nd February 1892:

« Concerning this dear and holy soul, allow me to tell you in confidence... I would like to have our Father Marie-Albéric do his theological studies, here of course, so that one day he might be advanced to the priesthood. I have not yet spoken to him about this plan, But I foresee that I shall have a serious struggle to contend against his humility.» (Lettres à mes frères de la Trappe, Cette chère dernière place, p. 91)

Similarly, Father Philomen had written on the 29th November 1891:

« My hope is that after his profession he will replace me as sub novice master, – I have held this position for so long – until such time that he is raised to higher responsibilities, as he well deserves. How happy I shall be to obey him.» (ibid., p. 86)

Brother Marie-Albéric confides his anxieties to Father Huvelin: he finds that the monks are not as poor as they should be, even though his letters never cease to express his attachment to the community, his peace and his submission. It is not pride on his part. But the monastery is situated in that part of Armenia where the people are human tatters, dying of hunger, and he feels pity for these poor people. The Muslim Turks are slaughtering the Armenian Christians, in this year of 1893, right up to the approach to the monastery. 160,000 dead will be counted. Brother Marie-Albéric is shocked to see that nobody comes to help these Catholics. He tries to alert the authorities in Paris, through the intermediary of his cousins, informing them of what is happening, but everybody knows and yet does nothing. So he wants to face the danger himself, to come to their aid, to die a martyr, but Father Huvelin advises him to obey his superiors, which is common sense. What would be gained from a few monks having their throats slit, when Europe is indifferent to it all!

Brother Marie-Albéric writes to Madame de Bondy:

«My soul is still in the same state: my thirst to seek the life of Nazareth outside the Trappist monastery increases from day to day; I am in peace, but I am very impatient for the hour to sound when this time of trial and of waiting will end and when I can go to where the good God is calling me.» (18 February 1896)

«My craving to exchange my religious state for that of a simple domestic or odd-job man for some convent is becoming more and more intense... The aspirations are the same but they become stronger each day. Every day I see more clearly that I am not in my place here; every day, I desire ever more to plunge to the lowest state of abasement, following the footsteps of Our Lord...» (19 March 1896)

It was then that Pope Leo XIII softened the Trappist regime. It worried Brother Marie-Albéric, for it was no longer the penance he had come to seek. He wrote to Marie de Bondy on the 27th June 1893:

«Let it be said between you and me, this is not the poverty that I would have wanted; it is not the abjection I would have dreamed of... on this side of things, my desires are not satisfied...»

«Pray for me, because at this moment the direction I see being taken by our order is moving further and further away from poverty, abjection, manual labour and austerity, which gives rise to sorrow and many thoughts in me.» (26 August 1893)

He confided these worries to Dom Polycarp and to Father Huvelin. Having first urged him to repel all these thoughts as temptations, Father Huvelin gave way, for he knew his man. He could see that Brother Marie-Albéric was following a supernatural appeal: « Since that is how things are, he wrote to Marie de Bondy, I am alarmed by this life he wants to enter, at the idea of this group he wants to form around him, but I hope he will keep with the Trappists.» (July 1895, Six, p. 159)

In the summer of 1895, he wrote to Charles authorising him to ask his superiors for permission to live according to his vocation, whilst remaining linked to the Trappists, but the superiors were opposed to this. Father Huvelin revoked his authorisation, but in 1896 he will approve Charles’s ideal, although regretfully: « I would so much have liked to keep you with a family where you are loved and to which you could have given so much.» (Castillon du Perron, p. 226)

For his part, Brother Marie-Albéric wrote to Marie de Bondy on the 8th July 1896:

«Father Huvelin has written me a letter dated 15 June, which I have only just received and which gives me the permission I have for so long yearned for: not only does he tell me that I can begin to take steps to look for my Nazareth outside here, but that I ought to... Thank the good God for having granted me this longed for grace of following Him... To follow the One you love hand in hand, to share His life and especially His prayers and His poverty is the sweetest of all sweetness and how I longed for this day...

«Now ask that your child may be faithful... He was in a tranquil boat; he is now throwing himself into the sea with Saint Peter and he has such great need of fidelity, faith and courage... that I feel my weakness, my incapacity, and all my wretchedness... the good God can do all... pray for me.» (Letter to Madame de Bondy, p. 60-61)

ABANDONMENT TO THE WILL OF GOD.

As soon as he had received Father Huvelin’s approval, Brother Marie-Albéric wrote to the Most Reverend Father General in Rome, Dom Sebastian Wyart, asking to be granted dispensation from his simple vows. At the same time he sent to his director, on the 14th June 1896, the Rule he had already written. Father Huvelin was appalled: « Your rule is absolutely impracticable... Whatever you do, found nothing.»

Now, at the beginning of 1897, he will have to take his perpetual vows or leave. His Abbot, Dom Louis de Gonzague, who loves and admires him, wants to keep this estimable monk. He decides to send him to Rome to continue his theological studies, saying to himself that, under the direction of Dom Sebastian Wyart, he will take his vows and remain in the order to become one of its pillars.

On the eve of leaving his brothers, Charles weighs up all the good he has received in the monastery. He writes to Raymond de Blic:

«These seven years have passed like a dream.»

For him, they were seven years of perfect life, in the greatest stability and strict monastic obedience.

On the 30th October 1896, he arrived in Rome and got down to his studies with ardour. He abandoned himself completely to the good will of his superiors who, like himself, he understands, are seeking only the Will of God. He meditates on the Old Testament and in recalling the sacrifice of Abraham, he writes:

«Good Shepherd, answer me. You know and You love these sheep; turn your eyes towards this one and tell him what he must do to give himself to You in the most complete manner.» (Méditations sur l’Ancien Testament, December 1896, Rome, quoted by Six, p. 179)

The 2nd February draws near, the day when he will have to pronounce his vows or leave the order for good. Dom Louis de Gonzague does everything he can to keep him.

On the 16th January, he goes into retreat and, with great relief, confides in Father Lescand, the student master, in whom he finds a true Father with an exceptional gift of discernment. He entrusts himself absolutely to the judgement of his superior, in a total death to himself, a death of obedience. For seven days, from the 16th to the 23rd January, he awaits God’s answer, ready to be a Trappist all his life if his Father General so orders. He is also ready to leave with happiness, and courage too, for this will not be an easy path, but will mean walking with Jesus, in His footsteps, towards the Cross.

Dom Sebastian Wyart calls his council and, on the 23rd January 1897, Brother Marie-Albéric learns that his superiors recognise his special vocation and encourage him to follow it under the direction of Father Huvelin. The Father permits him to leave for the East, as he wishes, and to live in poverty as a convent porter. But he implores him not to group other souls around him.

In the evening of the 23rd January, Charles writes a meditation on the Pater (cf. Lettres et Carnets, p. 46 sq., extracts, p. 19 bis). His heart is filled with peace. He has the strongest moral certitude that can exist on earth that his superiors’ decision expresses the Will of God. And he is happy that his vocation should have been confirmed in Rome itself!

The following day, he writes to Father Jerome, a Trappist at Staouëli, with whom he will maintain a regular and intimate correspondence:

«Obedience: it is the last and highest and the most perfect of the degrees of love. It is where one ceases to exist for oneself, where one annihilates oneself, where one dies as Jesus died on the Cross, and where one hands to the Beloved a lifeless body and soul, without will, without its own movement, with which He can do what He likes, as with a corpse: it is most certainly and without any doubt, the highest degree of love.» (Lettres à mes frères de la Trappe, Cette chère dernière place, p. 149)

A few days later, he left for the East without passing via France, having committed into Father Lescand’s hands his vow of perpetual chastity and poverty. To Dom Louis de Gonzague, who expressed a certain discontent with Brother Marie-Albéric’s departure, the Reverend Father General wrote on the 11th April 1897:

«Reverend and dear Father Abbot,

«Have you received news of Father Albéric? I have just received a delightful letter in which he tells me that he is in the service of the Poor Clares of Nazareth. His letter exudes a perfume of piety and of extraordinary contentment, which makes me believe that I was not mistaken with regard to his vocation. Allow me to tell you, concerning this, that I did everything within my means to keep this incomparable soul for you. When we meet, I shall tell you in detail the fight I put up to obtain the victory desired by Your Paternity. In the clearest possible manner, God imposed failure on me. Who can resist God?

«... Yours affectionately in Corde Jesu

Br. Marie-Sebastian Wyart, Abbot General o.c.r.»

CCR n° 292, January 1997

EXTRACTS FROM THE MEDITATION ON THE “ PATER ”

written in the evening of the 23rd January 1897

« May thy will be bone on earth as it is in Heaven. »

This request is exactly the same as the two previous ones: it asks for the same two things, the glory of God and the sanctification of men... What in fact does it mean to ask that men do God’s will, other than to ask that they be saints?... and it is in the very sanctity of men themselves that God’s glory on earth is made manifest. That shows how much He had these two objects at heart, how much they were at the bottom of all His sighs and of His prayers, as they were, moreover, the end of His life here below... It also shows me how much all that is involved in glorifying God and doing good to souls gladdens the Heart of Our Lord since it conforms to His most ardent desires and to His whole life’s work.

It shows how greatly any offence against God and all that retards a soul’s sanctification pains His Heart, since it is in direct opposition to what He most ardently desires, to what He asked of His Father every day, with tears and sighs, and for which He gave all His blood. We thereby see how those who, like the blessed Saint Teresa, experience a pang of anguish, an extreme suffering at the sight or the hearing of the least sin committed by anyone, have the spirit of Our Lord, Who Himself experienced exactly the same pain in such a case, since He so ardently desired, since He so keenly loved and chose the praise and honour of His Father and the sanctification of men.

We also see how little of Our Lord’s spirit they have, who can see and hear of sins committed without feeling sorrow...

Unless one feels this keen sorrow at any offence against God, as was felt by Saint Teresa, and still more by Our Lord, one does not have a real love for the manifestation of God’s glory, one is very far from having the spirit of Jesus. We should, therefore, have an extreme joy in and desire for every good action, an extreme zeal for producing good and an extreme sorrow and fear of everything that gives offence to God and an extreme zeal to avoid every least offence (it is in this spirit that Our Lord chased out those buying and selling in the Temple; that Saint John Chrysostom wanted the faithful to admonish, and even beat, bypassers, unknown persons, whom they heard blaspheming).

« Give us this day our substantial bread. »

With these words, what are we asking for, oh my God? We are asking for today and, at the same time, for this present life, which lasts no more than a day, the bread that is above every other substance, that is to say, supernatural bread, the only bread necessary for us, the only one for which we have an absolute need if we are to attain our end: this uniquely necessary bread is grace...

However, there is another supernatural bread which, though not absolutely indispensable as is grace, is indispensable for many and is the good of all good – this other bread, whose very name of bread gives us the thought, and which is a very sweet and a supreme good, – it is the Most Holy Eucharist. But above all, note that in asking for this twofold bread of grace and of the Eucharist, I am not asking it for myself alone, but for us, that is to say, for all men... I make no request for myself alone; all that I ask for in the Pater I ask either for God or for all men.

To forget myself, to think only of myself and of my neighbour, of myself alone in view of God and to the same extent of others, as is proper for one who loves God above all, above neighbour as well as self - that is what the Lord makes me practise at every request of the Pater, not to pray for myself alone, but to be concerned to ask for all men, for all of us, children of Our Lord and loved by Him, for all of us whom He has redeemed with His Blood.

(Charles de Foucauld, Lettres et carnets, p. 50-52.)