SAINT CHARLES DE FOUCAULD

3. The French Officer

SAINT-CYR.

Suddenly subjected to the frugality of military life and to numerous physical exercises, Foucauld rapidly lost his surplus fat. His tailor-made uniform, made to measure in view of his corpulence, became too large for him. He had to wear another one !

From glimpses of his character, from his culture, his brilliant memory, and his amazing capacity to assimilate courses he had not attended by rapid reading, his comrades see in him a man of keen intelligence. However, he shows himself to be singularly indolent and applies himself minimally to work. Polite, well brought up, disciplined, he is not poorly rated. He does not make himself disagreeable, but he is not very approachable ; he is « withdrawn, talks very little and rarely laughs ». However, though distant, dilettante and pleasure loving, he remains a gentleman and wishes to serve his country. At the end of his first year, he passes out 143rd from an overall class of 391.

On the 1st February 1878, Charles is summoned urgently to Nancy, and two days later his Grandfather, Colonel Morlet, died. He showed no sadness at this, so wrapped up was he in his egoism. Until that day, his Grandfather’s presence had still exercised a certain restraint on him. Now, there was nothing left to curb him. There is only his little sister, Mimie, whom he loves greatly, but she has no influence over him. Furthermore, he inherits an enormous fortune : he comes into possession of a six hundred thousand pound annuity. A millionaire at the age of twenty ! He then throws himself headlong into a life of debauchery and dissipation. He attends his courses even less. He no longer even stands up straight ; he lets his hair grow and his trousers are dirty and unstitched. He begins to be poorly rated. The punishments fall thick and fast : in two years he will be punished forty five times and collect forty seven days confined to barracks.

He leaves Saint-Cyr 333rd out of 386. Having obtained a place in the Cavalry, he enters Saumur on the 2nd October 1878.

SAUMUR.

His room mate is his best accomplice from Saint-Cyr, Antoine de Vallombrosa. They have an affinity through birth, fortune and tastes. Their room becomes a veritable club. Charles is firmly resolved to make the most of life. He smartens up and organises his pleasures : parties and suppers. He even invents a pâté !

As for his military duties, he does only what is obligatory and is not interested in promotion. The two friends nonchalantly pick up days of confinement to barracks. In order to thumb his nose at the General, Charles even goes as far one day as to disguise himself as a woman, feigning to have introduced one of his ladies into the school !

He is unstoppable. He does not draw his pay ; he is very generous, though discreet. He does not hesitate to lend. He manages to help one or the other without it being known. His tact and his heart are unanimously recognised and his humour disarms the most critical. He never reproaches others when he is caught out. His mind concentrates on things and institutions, never on his friends.

Yet, he is not happy... Unable to stand it any longer, he absconds twice. General L’Hotte keeps him under close arrest and warns his family that he is thinking of discharging him. The cup is full. His aunt Inès Moitessier sends him an extremely severe letter. If he continues, she will disown him. He then digs his heels in : he is ready to break with his family when, fortunately a letter arrives from Marie de Bondy. Through her tenderness and sweetness, she moves him ; she does him good, and he agrees to make it up with his aunt.

Charles leaves Saumur 87th out of 87. He is posted to Sézanne, where he is bored to death, and he asks for a change. Six weeks later, he is moved to Pont-à-Masson where most of the cavalrymen of the 4th Hussars are to be found.

WITH THE 4TH HUSSARS.

At Pont-à-Masson, he finds another crony, the future duc Jacques de Miramon Fitz-James. They live it up like grand lords and libertines. They organise dinners of unparalleled refinement and dazzling balls ; the revellers provoke one another to duels. But the more splendid the parties, the sadder he feels. In his retreat at Nazareth, he will write :

« You made me feel, my God, a sorrowful emptiness, a sadness that I never experienced except then... it would return to me every evening, when I found myself alone in my apartment... it held me mute and overwhelmed me during what are called parties : I organised them, but when the moment came, I spent the time in a state of speechlessness, disgust and boredom... You gave me this vague anxiety of a bad conscience which, dormant though it was, was not quite dead. I have never felt such sadness, such a malaise and such anxiety except then ! »

(Nazareth retreat, “ Me, my past life ; God’s Mercy ”, 8 November 1897, in Charles de Foucauld, “ La dernière place ”, published by Nouvelle Cité, 1974, p. 101-102)

After such nights of pleasure, very early next morning he would be on horseback with the others. He proved to be a vigorous horseman, full of stamina. His troop loved him as much as he respected them. On manœuvres, he always knew what he was about. And when he submitted reports to his superiors, they complimented him on his work even though he wrote them off the cuff ! As he was much too fat, his men called him “ le Père de Foucauld ”, meaning “ mate ”.

Numerous women passed through his life, as objects of pleasure, but nothing more. One of them, Marie C..., did, however, hold his attention and knew how to cheer him up. He decided to install her in his life officially.

When his regiment was sent to Algeria, he introduced her as his legitimate spouse. His colonel found out about this and thought it was in very bad taste. He summoned him and ordered him to send away his mistress. Charles refused ; yet he was happy in Algeria. He came back from his expeditions with notebooks full of information about the customs of the Kabyles. As for sending away his friend, no, he could not bring himself to do that. It was not that he was so deeply attached to her, but his heart of gold could not bring itself to hurt her.

On the 20th March 1881, he was struck off the Army lists and put « in non-activity through withdrawal of employment, for indiscipline as well as notorious misconduct ».

After organising a sumptuous farewell dinner, Charles and Marie embarked for Évian.

DID HE HAVE A MILITARY VOCATION ?

In appearance, Foucauld accepted this decision very placidly, but in reality he was braving it out. Why ? Because for him this was but another sanction. He knew that he would be back. This was a kind of leave given to this enfant terrible on the part of a paternal authority. In effect, the Army was his second family, and to leave it would be to orphan him twice over. He is a soldier and he found in the military world the necessary framework for his being to blossom, for he needed the firmness and manly commitment involved in serving the good. In the person of the colonel or of the general, he found the father he was missing. So when his superiors reproach him for his bad behaviour, he appears to be rebellious and pigheaded... but in reality their warnings strike home, and he will not forget them.

Contrary to those who persist in portraying Charles de Foucauld as an antimilitarist, our Father pursues his analysis in a way that is enlightening. He points out that at that time the French army constituted a body in two halves, divided according to two different vocations. The metropolitan troops were preparing for “ the revenge ”, in order to re-take Alsace and Lorraine, their eye fixed on “ the blue line of the Vosges ”. Officers, like Pétain, in the same year as Foucauld, and Castelnau, were studying and teaching tactics and strategy with a view to the coming confrontation on the eastern frontier.

The colonials, on the other hand, thought only of endowing France with an empire, to increase her power : they loved perilous and heroic expeditions, dangers and adventure with men full of courage, idealism and endurance.

As for Charles de Foucauld, he loved the Army, but... garrison life bored him ! He complained about it in letters he wrote to his friend, Gabriel Tourdes :

« For nothing in the world, do I wish to live the life of the garrison... » « I detest garrison life ; I find the experience deadly... » « We are bored with ourselves more than ever, and they bore us more than ever. »

(Lettres à Gabriel Tourdes, published by Nouvelle Cité, 1982)

But given the chance of an expedition, he enlists without delay ! He will be the greatest of the artisans of French restoration through the imperial organisation.

TRANSFORMATION.

May 1881. Only two months have passed since he was classed as being in “ non-activity ”... Our troops in Algeria are focusing on Tunisia. A victorious expedition. But since the Southern Oranais were poorly defended, Bou Amama raised the standard of the Holy War in that area. The 4th African Chasseurs moved, therefore, towards South Oranais. Foucauld learns of this at Évian. His heart skipped a beat : his comrades are in danger ! Leaving his mistress there, he goes straight to the War Office and asks to be re-integrated. They refuse. He then hands in his resignation as an officer in order to enlist as a simple spahi. Service, before all else ! The authorities were touched by this very generous willingness and re-integrated him in his rank. He was sent to the 4th Chasseurs in South Oranais. It was the 3rd June 1881. On the 9th July, Charles de Foucauld was on active service. The rebels are pursued, but each time they disappear into the Sahara and take refuge in Morocco.

Charles proved himself to be a true soldier and a real leader in that campaign. With his toughness, discretion and reserve, he immediately won his comrades’ esteem. He bore every privation and fatigue ; he undertook the roughest work with no fear of mixing with the men of the troop and depriving himself of necessities for their sake.

He fought together with two men who, like him, believed in France’s colonial future : Henry Laperrine, who already held the rank of lieutenant at the age of twenty-one, and Baron de Motylinski, an intelligence officer and the company’s interpreter. Charles eagerly listened to his friends and did not miss a chance to learn.

With peace restored, he can no longer be content with garrison life. He has understood the difficulty of French colonisation and he requests leave in order to travel in Southern Algeria. His request is refused. He therefore resigns, on the 28th January 1882. His family are worried, thinking that he has had another brainstorm. They make him take sound advice from his cousin Latouche. But Charles still regards himself as an officer : he wishes to serve France as an “ enfant perdu ” (a lost child) so as not to compromise the Government.

He thought first of exploring South Algeria, but he understood that the Moroccans made the most of their strategic advantage to sweep down towards South Oranais, raiding and disturbing French peace. So he then decided to penetrate Morocco and explore it so that one day our troops might conquer it...

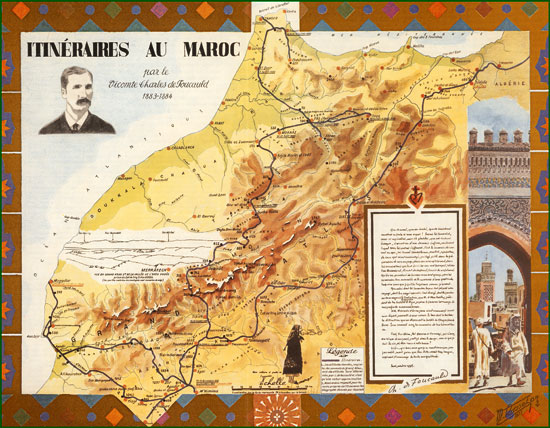

RECONNAISSANCE IN MOROCCO : 10TH JUNE 1883 – 23RD MAY 1884.

This expedition places Charles de Foucauld among the greatest explorers of all times, but the glory of this exploit was overshadowed by that of the hermit and of the saint he was to become.

Foucauld settled, therefore, in Algiers, where he stayed for more than a year meticulously preparing for the expedition with the help and advice of MacCarthy, the town’s librarian and former explorer of the Sahara. He learned Hebrew, Arabic, topography and the use of the sextant. He provided himself with a compass, a chronometer, an oil barometer to measure altitude, and a thermometer. To think that Morocco was then a blank patch on geographical maps : they still went by the information given by Jean-Léon the African (1518) ! As this country is extremely xenophobic towards Europeans, it is only possible to penetrate it under the guise of the greatest abjection, poverty and squalor. Since the Jews are despised by the Arabs, it is as a Jew that Charles will enter Morocco, under the name of Joseph Alleman, accompanied by an old and real Jew : Mardochaeus.

Having calmed the fears of his family and overcome the opposition of his legal adviser, he can finally leave with Mardochaeus, on the 10th June 1883, to discover the forbidden land.

Oran, Tlemcen, Lalla Marnia, Nemours, the frontier town. They are driven back, and so they set sail for Tangiers, the principal port of Morocco.

They cross the Rif towards Fez and visit Tétouan, Chechaouene, a town from which no European has ever returned ! Furthermore, they barely escape death. Foucauld notes what he discovered : the filth and the squalor of peoples constantly oppressed by brigands.

At Fez, a cry of admiration before this Moroccan capital. Then, in order to prepare the paths for French penetration, he makes his way towards Taza. In this town situated on a rocky barrier overlooking a deep and rather narrow gorge, he discovers a very friendly people, always being killed, oppressed and enslaved by a cruel tribe, the Riata. These poor people never cease begging the French to come and deliver them : « When shall we live in peace, like the people of Tlemcen ? » they ask. « It’s not far ! What are the French waiting for ? »

He returns via Wadi Inaouene, as Lyautey will do thirty years later, again passing through Fez and then on to Sefrou and Meknès where he is the first European to penetrate. In “ Bled el-Makhsen ”, it is the brigands who rule : here too, the inhabitants are only waiting for the French. And these are the indisciplined territories of the “ Bled es-Siba ”, the forbidden land. Only just saved from certain death, he makes his way towards the Atlas through the desert of Tadla. At Boujad, an important and leafy “ zaouia ”, he is well received by El Hadj-Idriss and his father. They are Berbers, an open and honest race. Their conversation is confidential, for Idriss lets him understand that he has recognised him as an explorer sent by his government to prepare for the arrival of the French. « How rich this country would be, he said, if it were governed by the French ! They will come soon ! » Twenty-four years later, in 1907, Idriss will welcome General Drude in Casablanca and will be France’s best helper in penetrating central Morocco. By forging a friendship with him, Foucauld was indeed the starting point of the colonisation !

But he sets off again : Casbah Tadla. He climbs the Atlas (4000 m high) and goes via the Telouet pass (2650 m). From there, he discovers the Sahara, the great black stoned Hamada. He progresses in an incredible solitude and amid incessant dangers. He reaches the oases, visits that of Tisint and from there the neighbouring oases. If penetration is impossible from the North, it will have to be planned from the South, especially as it is from that direction that the rezzous pass as they sweep down on Algeria ! Then Mrimina, whence a Harratin friend has to come to deliver him with his harka.

He stops fifteen days at Mogador, time to receive the necessary money to continue on his way. Back in Tisint, he climbs up from the other side of the Middle Atlas, through the valley of Moulouya, always accompanied by Mardochaeus. Wadi Dra, the Djebel to the East, the gorges of Todra : Ksar-es-Souk. From there, he sees Tafilalet. They escape an ambush, and they arrive facing Oudjda : that is in fact the way through which our troops will pass in 1903. They cross what passes for a frontier, and on the 23rd May 1884, they are at Lalla Marnia, in French territory. Foucauld immediately presents himself at the military guard house, but the lieutenant finds it difficult to recognise in “ this squalid Jew ” he who was once “ the arbiter of French elegance ” ! It was a radical transformation which no one could have imagined.

SERVING THE FRENCH COLONIAL EMPIRE.

On his return, Foucauld will work for two years editing his book “ Reconnaissance au Maroc ” : 495 pages, to which will be added twenty pages of maps reproducing the regions of Morocco on a scale of 1/250 000. Some 680 km of routes were already known ; he added the exact course of the 2, 250 km of tracks covered, with detailed information about relief, vegetation and the possibilities of irrigation.

He determined forty five longitudes and forty latitudes, and where only a few dozen altitudes had been known before, he added three thousand.

As for the human geography, his observations were so psychologically exact in their analysis of native society, that the officers for Native Affairs will know the Moroccan, Arab and Jewish soul in advance, the customs of the tribes and, above all, the disorder and the wretchedness of these poor countries, subject to raids and endemic famine... He also discovers Islam as a simple, popular religion, but with a moral code that leaves men to their own instincts and fails to raise them above their nature !

Most of the biographers have attempted to explain Charles de Foucauld’s exploit by “ The call of silence ” (Bazin), a desire to rehabilitate himself in the eyes of his family (Carrouge), pride and the will for power : “ a worldly rage to understand, to see and to know ” (Six and Massignon). Our Father roundly refutes these theories and shows us the truth in a definitive manner : Foucauld was a well born man, an aristocrat of a military dynasty, a soldier at heart and in love with the service of France. Out of pity for the Moroccan populations, living in perpetual terror of the rezzous, and through a desire to see the French Empire extended over all Africa, he went in the vanguard of our armies ! He is not an explorer strictly speaking ; he is first and foremost an officer on a reconnaissance mission.

There is no other explanation for his bravery in danger, his physical courage, his tenacious will, asceticism and renunciation other than as dedication to a higher cause : the French Army. It is Lieutenant de Foucauld who, acting against the inertia of the Republican government, will find a way of sparing the lives of those valiant soldiers, always uselessly exposing themselves to death in ambushes in pursuit of the rebels. And, in the end, what he gives to those poor peoples is French peace.

This “ reconnaissance ” is what gave him a passion for the colonial Empire, and will finally carry him further. For he poses the question : what to do with the Morocco of the future ?

His patriarchal sentiment is reawakened in the face of the Berber race which he discovers as a feudality : it reminds him of the great lords of the Middle Ages, the protectors of their people. He is charmed by the uprightness of the Berber people, not yet affected by Islam and quite hostile to Arab cunning.

The future Morocco he sees as French. This most beautiful country will be even more beautiful when the French are there, arousing this civilisation from its lethargy and forming elites, when the peasants are no longer being raided, when the land is irrigated and when there are roads ! In the meanwhile, these people are in a pitiful state and they must be pulled out of their wretchedness.

And why this civilising work ? On this point, there is a confrontation between the unbelief of Charles de Foucauld and the religious soul of these peoples. These Jews and these Arabs, whose morals he describes as execrable, nevertheless believe in a God, and the foundation of their civilisation is God. Allah akbar, God is great ! This train of thought will lead him to make a profound return to his own traditions. French penetration and colonisation : yes, but why ? To teach what ? Republican and revolutionary dogmas ? It is this question that will bring him back to his family’s traditions, in order to continue them... and these traditions are Christian ! Remember that it was the lands of Lardimalie that he wanted to visit on his return from Morocco.

That is how the service of the French officer, taken to the lengths of extreme heroism, will gradually and slowly lead this soul to recover the fullness of the faith.

What lessons for us ! Like Saint Augustine, Charles de Foucauld is an example of conversion – a very attractive example for youth of all times. Let him be canonized ! Let the crowds learn about his life, and it will cure them of all today’s mental and moral disorders ! Unfortunately, because of the “ diabolical disorientation ” blowing a storm throughout the Church, his beatification dossier has been relegated to oblivion. His whole thinking on colonisation is horrifying to modern minds ! Our Father, however, has long since made it his own and has not ceased preaching it in his writings and in his news conferences as the only possible remedy for the dramas of Lebanon, Yugoslavia, Algeria, Somalia and Rwanda, and many other countries sinking one after the other into war, anarchy, terror and famine, thus fulfilling the prophecy of Our Lady of Fatima : « Several nations will be annihilated. » (cf. CRC, Eng. ed., n° 290, p. 6) It is in this fidelity to Father de Foucauld that our Father has ceaselessly battled, to the point of being imprisoned (1962) and dismissed from his parishes (1963), so that Algeria and our whole Empire might remain French ! In the same way, he will not cease to propose, as a remedy to the dangers of immigration, the integration of foreigners into the French army, that they may be civilised and converted and, if they show themselves worthy of it, become fully fledged Frenchmen.

CCR n° 291, December 1996

RECONNAISSANCE IN MOROCCO

In an article entitled “Itinéraires au Maroc”, and published in the Bulletin of the Paris Geographical Society (1st quarter 1887), Charles de Foucauld summarizes his travels and his work. Furthermore, the author unintentionally gives us a striking portrait of himself. We shall quote here only the most curious passages about the precautions taken by the explorer in the course of his travels.

«The Sultan of Fès, he writes, is master of only a small part of the territory assigned to him on our maps: about a fifth or a sixth. The rest is free and occupied by independent tribes, of various races, languages, habits and customs, each tribe living as it pleases: some as a monarchy, others as a republic. Over the Sultan’s territory, the European can travel openly and without danger; in the rest of Morocco, he can enter in disguise and then at the peril of his life: he is regarded as a spy and would be massacred if recognised. Nearly all my travels were in independent countries. From Tangiers I disguised myself to avoid any awkward recognition. I passed myself off as a Jew. During my travels, I dressed as a Moroccan Jew, I practised their religion and I gave my name as Rabbi Joseph. I prayed and I sang in the synagogue, I mounted the sifer, parents begged me to bless their children. If anybody asked me my place of birth, I would answer sometimes Jerusalem, sometimes Moscow or else Algiers. And if I were asked the reason for my journey? For the Muslim I was a mendicant rabbi begging from town to town; for the Jew, I was a pious Israelite come from Morocco, despite fatigue and danger, to enquire about the condition of his brethren. The state of being an Israelite involved all sorts of unpleasantness: walking bare foot in towns, sometimes in gardens, receiving insults and stone throwing was nothing: but to live constantly among Moroccan Jews, the most contemptible and repugnant of people, with some rare exceptions, was an intolerable torture. They spoke to me open-heartedly as a brother, boasting of criminal actions and confiding shameful sentiments to me. How often have I not regretted the hypocrisy involved! All this trouble and disgust was compensated by the ease of travel afforded by such disguise. As a Muslim I would have had to live in common, always in the open and always in company; never a moment’s solitude; always eyes fixed on oneself; difficult to obtain information; even more difficult to write; impossible to use instruments. As a Jew, these things did not become easy, but as a rule they were possible.

«My instruments were: a compass, a watch and a pocket barometer, in order to pick out the route; a sextant, a chronometer and a spirit level, for observing longitudes and latitudes; two other holosteric barometers, various thermometers for meteorological observations... My whole itinerary was picked out by the compass and the barometer. Whilst walking I always had a five centimetre square notebook hidden in the hollow of my left hand, and a two centimetre long pencil never left my other hand. I noted down anything remarkable along the way, what could be seen to right and to left; I noted changes of direction, together with compass bearings, unevenness of the ground, stops, the rate of speed of progress, etc. I wrote practically the whole of the time along the route, and all the time in hilly regions. Nobody ever noticed me, not even in the most numerous caravans; I took the precaution of walking on ahead or else behind my companions so that, with the aid of my ample garments, they could not distinguish the slightest of my hand movements; the contempt inspired by the Jew was favourable to my isolation. The description and survey of the itinerary thus filled a certain number of small notebooks; as soon as I arrived in a village where I could have a room to myself, I completed them and copied them out into proper notebooks which formed my log book. I spent my nights doing this; during the day I was ceaselessly surrounded by Jews: to write at length in front of them would have roused suspicion. The night brought solitude and work.

«To make astronomical observations was more difficult than picking out the route. The sextant cannot be concealed as can the compass, and it takes time to use it. Most of the sun and star heights were taken in villages. During the day, I watched out for the moment when nobody would be on the roof top of the house, and then I would take up my instruments wrapped in clothes which I said needed to be aired. Rabbi Mardochaeus Abi Serour, an authentic Israelite who accompanied me on my travels, remained on guard on the stairway; his mission was to distract with interminable stories anyone attempting to join me. I began my observations, choosing the moment when nobody was looking from the neighbouring roof tops; very often I had to interrupt them. It was a very long process. Sometimes it was impossible to be alone. What stories were not invented then to explain the exhibition of the sextant? Sometimes it served to see the future in the sky, sometimes to give news of those absent. At Taza, it was a preventative against cholera; in Tadla it revealed the sins of the Jews, elsewhere it told me the time, what the weather would be like, warned me of dangers ahead, and I don’t know what. During the night, I could work more easily; I was nearly always able to act in secret. Very few observations were made in the open country, where it was difficult to isolate oneself. Sometimes I managed, with the excuse of prayer: as though to recollect myself, I would go some distance, covered from head to foot with a long sisit, the folds of which would hide my instruments. A bush, a rock, a fold in the terrain would conceal me for a few minutes, and I would come back having finished my prayer.

«To trace the contours of the mountains and make rough topographical sketches needed even more mystery. The sextant was an enigma that revealed nothing; French writing guarded its secret; but the least drawing would have betrayed me. On the roof tops as in the open country, I only worked alone with the paper hidden and ready to disappear into the folds of my burnous.»

On the other hand, Charles de Foucauld was to encounter certain difficulties with his guide, Mardochaeus Abi Serour. This is what he will write on the subject some years later:

«I have said very little about Mardochaeus in the account of my travels; I have hardly mentioned him. Yet, he played a very important part, for he was responsible for dealing with the natives and all the material cares fell to him... An intelligent man, very, even too prudent, infinitely crafty, a fine speaker and even eloquent, a rabbi with sufficient learning to command the respect of other Israelites, he was of great service to me: I must add that he always showed himself to be vigilant and dedicated to watching over my safety. If I have kept silent about all these services, it is because he was at the same time, through his contrariness, a constant and considerable obstacle to the execution of my travels; whilst contributing to the success of my enterprise, from first to last, he did everything that was in him to make it fail...»

«The truth is, as the Marquis de Segonzac has so rightly said, that there was between the two men an irreparable incompatibility. Foucauld was young, ardent, resolute, tracing his itinerary in advance to stop himself from making any changes; and Mardochaeus was old, timorous, accustomed to getting round obstacles and avoiding all resistance. And then, Foucauld’s travels lasted eleven months; for Mardochaeus they had lasted fifty years! The one was at the beginning of his course, the other had reached the end of his long wandering and aspired to nothing more than security and rest.»

No matter what, it has to be recognised that this rabbi, for all his indolence, at least once endangered his life for his master.

(Charles Gorrée, Au service du Maroc, “ Difficultés de l’exploration”, Grasset, 1939, p. 119-125.)