The Dawn of Islam and the Genesis of the Qur’an

“ Once upon a time there was a poor Arab camel driver named Mohammed. Although an illiterate orphan, he was tormented by the mystery of God. He eagerly informed himself when he happened to meet Christian monks about all the beliefs of his time and, already he was unconsciously elaborating his personal synthesis of so many disparate dogmas. It was then that he received a revelation from Allah who spoke to him through his archangel Gabriel. Today, this revelation constitutes the Qur’an, a religion so pure and so perfect that it conquered for over a thousand years many Christian peoples from the East and the West.”

In an article of February 1980 outlining his programme, our Father, Georges de Nantes, evoked in this way the beginning of this “Tale of A Thousand and One Nights,” which constitutes the story of Mohammed and the expansion of Islam in the 7th and 8th centuries, as it has been handed down to us by Muslim tradition.

Scholars, such as Fr. Lammens, a Jesuit at St. Joseph University in Beirut, had already provided striking proof of the purely legendary character of the historical Muslim tradition by showing that it is entirely drawn from the Qur’an. Fr. Lammens thus observed that the Sîra, i.e. the life of Mohammed “ comes not from two parallel and independent sources, mutually complementing and verifying one another, but from a single one, the Qur’an, slavishly interpreted and developed by the Tradition following preconceived ideas [...] attempting to specify the meaning, to put everywhere dates and proper names. The product of this exegesis, carried out haphazardly, is that the Sîra remains to be written, just as the historical Mohammad remains to be discovered.”

What does this tradition tell us? For example, it relates that Muhammad was born at Mecca. Mecca, however, is absent from all the ancient maps of the Arabian Peninsula. This poses the enigma of the location where the founding events of Islam took place! As for the author of the Qur’an himself, Mohammed is not in attested history any more than “Mecca” is in true geography.

As for Fr. Lammens, he did not attempt to resolve these two enigmas, nor did anyone after him. In fact, whoever wants to translate and comment on the Qur’an, or even to determine the history of the earliest period of Islam, comes up against a major difficulty. Either he will have recourse to the abundant, but legendary Muslim literature on the subject, or he will decide to reject totally this legend dating from a later period; in that case he will be confronted with an incomplete history that is difficult to reconstruct, and he will have to make do with the few reliable historical and archaeological elements that he has at his disposal at the present time, even if it means leaving a certain number of questions unresolved!

This was the course that our Father chose in 1957 when it became obvious to him that it would be necessary to apply to the Qur’an the historico-critical method that had long been in use in the study of the Bible, which would entail explaining the Qur’an by the Qur’an. This considerable exegetical work was entrusted to Brother Bruno Bonnet Eymard and the result is a translation and systematic commentary on the first five suras. This was achieved without the slightest recourse to what must be referred to simply as “the Muslim legend.” Brother Bruno essentially used Holy Scripture, in the Hebrew language, but also positive historical data.

It is this “true history” of 7th and 8th century Arabia that we must rediscover today in order to attempt to understand how the Qur’an and Islam made their apparition.

In part one of this article, we will start by considering “Arabia” which, before Islam, was Christian. This will allow us to understand our Father’s and Brother Bruno’s increasingly corroborated conclusion: the Qur’an germinated in a Christian breeding ground!

In part two, we will focus on the events that took place during the war between the Byzantine Empire and Persia in the years 603 to 628, those pertaining to our subject: the capture of Jerusalem by the Persians in 614 and the dawning of an “era of the Arabs” following the great victory of the Byzantines over the Persians in 622.

In part three, we shall consider a few significant aspects of this Arab domination in the entire Near and Middle East during the first century of this Arab era, which will lead us in part four to focus on the new “heresy of the Ishmaelites.”

WHEN ARABIA WAS CHRISTIAN.

CHRISTIAN CIVILISATION IN ARABIA.

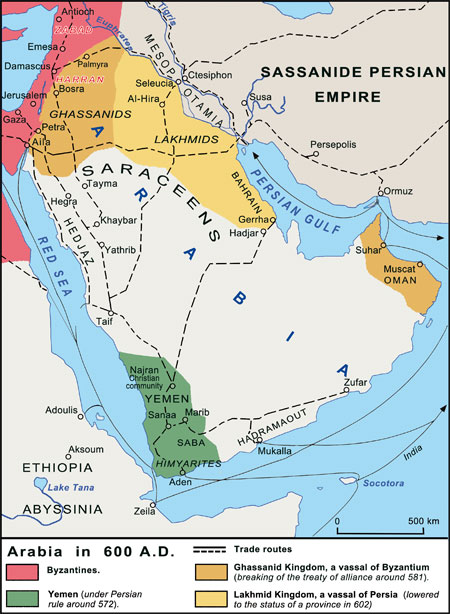

What is “Arabia?” At the beginning of our era, it designated the land of the Arabs. “ It is hard to be more specific since the ‘Arabs’ were defined by nomadism and were spread over an area that included the whole territory of Syria, as well as the Eastern Desert up to the Euphrates, Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Sinai Peninsula, the Kingdom of the Nabataeans and Arabia Felix.” » (Michele Piccirillo, o. f. m., L’Arabie chrétienne, Milan, 2002; the French adaptation is published by Ed. Mangès).

The Gospel began to spread throughout Arabia shortly after Pentecost, as shown by the Acts of the Apostles, which indicates the presence of Jews originating from Arabia in Jerusalem during the feast day (Ac 2:5-11). It came from Jerusalem then spread to the East through the Perea region, located east of the Jordan and inhabited by Jewish communities of Essenian allegiance.

When Emperor Trajan founded the Roman province of Arabia, after the annexation of the Kingdom of the Nabataeans in 106, Christianity had already spread through the cities and the countryside, even though the presence of the Christian community is only attested in sources beginning in the 3rd century. The blood toll paid by the Christians of the province during the great persecution carried out by Diocletian in the 4th century bears witness to its vitality.

MISSION AND COLONISATION

The advent of the Sassanids in Persia during the first half of the 3rd century brought about the closing of the trade routes between the Roman Empire and the Far East. The caravan trade from Palmyra that until then had ensured the economic prosperity of the nomadic tribes from the Arabian Peninsula to the Syrian Desert was destabilised by this disruption and the Roman territories were then subjected to raiding by the Saracens.

While seeking to protect themselves from the incursions of pillagers, Rome attempted to re-establish the trade routes by creating a system of satellite States in central Arabia. The emperors therefore began to grant the status of ‘federates’ to Arabs by establishing “phylarchs” under the supervision of military authority. For the tribal chiefs it was a real gain in authority and for the Empire the hope of furthering Roman and Christian influence in central Arabia, which would constitute a threat on the flank of the Persians.

Under Constantius II (337-361) the court of the king of Himyar in the south of the peninsula thus received an embassy around 340. Although this embassy was well-received, in the end, this first Roman and Christian endeavor was thwarted on the religious level by the Jews. Already well-established in Yemen, they were in constant contact with the rabbinical school of Tiberias, the cradle of the renewal of synagogal Judaism. This embassy was also foiled by the Persians to whom the native Himyarite dynasty would soon pay tribute.

During their bloody incursions in the north of the peninsula, the Saracens met the monks of the desert. Through contact with them, some of Saracens converted, enthralled by the charisma and the miracles of a ‘marabout.’ This is how St. Euthymius founded Paremboles in Palestine by converting an entire tribe who refused to serve as an antichristian police force for king of Persia. Bishop Theodoret of Cyrus described Simeon Stylites’ role in the conversion of those whom he referred to as the “Ishmaelites,” using a biblical term. The accounts recall that the chiefs and their tribes put themselves at the disposal of the Romans in order to defend the Empire’s borders against the Persians and their vassals, the Lakhmid Arabs of Al-Hira (already organised as a kingdom since the 4th century,) and participated in the campaigns against the Palestinian Jews. Here we can see that the political alliance with Rome went hand in hand with the Christianisation of the tribe placed at the head of the confederation.

In an attempt to bring a permanent halt to Arab incursions, around 529, Emperor Justinian gave the Ghassanid Al-Harit, who had already been made ruler over the Arabs of Palestine, a title even better than phylarch: the title of patrician, accompanied by all the epithets that in Byzantium designated the members of the highest aristocracy. As for the Arabs, they called him “king,” the very title given to the emperor. The ‘Ghassanid barrier’ had been created, stretching from southern Palestine to the region of Palmyra.

TOWARDS A CHRISTIAN ARABIA?

Excavations carried out in the territory of the ancient province of Arabia have shown that its greater part was occupied by Arab populations perfectly integrated into the new Christian society.

Protected from the incursions of pillagers and Persians by the Ghassanid kingdom, the Roman province of Arabia experienced a veritable apogee in the 5th and 6th century, a consequence of the fact that almost the entire population adhered to Christianity. The conversion of nomadic tribes established relationships of trust between them and the sedentary populations, as well as with the Roman authorities. The most beautiful architectural and artistic expression of this apogee was the construction of many churches decorated with mosaics, the fruit of an outpouring of generosity from the Empire’s central government, local notabilities and Banu Ghassan phylarchs.

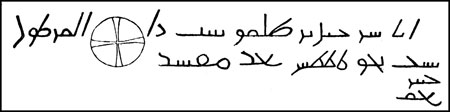

It is against this background that Arabic in its written form appeared. It originated, as our Father wrote in his afterword to Volume 2 of the translation of the Qur’an, “ not on the trails of the Hedjaz [...], but under the sign of the monogram of Christ, sculpted on the pediments of the churches in North Syria.” In fact, there are two inscriptions: one discovered in Zabad, on the lintel of the gate of a basilica dedicated to St. Sergius, dating from 512; the other in Harran dating from 568, in Syria also, north west of Djebel Druze. It is on the lintel of a martyrium dedicated to St. John the Baptist. They are the most ancient specimens of the use of the Arabic alphabet. The two inscriptions bear witness to the fact that in the 6th century the Arabic language and writing were fixed and used in the Christian communities of Syria, together with Greek and Syriac.

At the beginning of the 7th century, thanks to the efforts of monks, all the Arabs of Mesopotamia, Syria and the Province of Arabia had become Christian to some extent, at least by ambience. They had all seen the solitaries or the ascetics and had eaten on the breadline at the gates of monasteries. They had witnessed the controversies between the Monophysites and the Dyophysites and had opted for or against the human nature of Our Lord with varying degrees of discernment.

In the south, the Kingdom of Himyar reached its apogee under King Abraha, after a persecution instigated by the Jews and victoriously fought by Ethiopia with the support of Byzantium. Ethiopia reestablished a Christian dynasty there around 525. In 543, Abraha had a church consecrated on the dam of Marib that he had just had reconstructed. Not only Emperor Justinian and the king of the Banu Ghassan, but also the king of Persia, Chosroes I and the king of Hira, his vassal, as well as the Negus, sent emissaries to congratulate him, thus attesting to the prestige that the king of Himyar enjoyed in Arabia Felix. “ All of this,” our Father analysed in the afterword of Volume 2 of the Qur’an, “ reveals to us an Arabian Peninsula that was in the process of forming a perfect Christian realm under the reign of Abraha.”

Unfortunately, it was the opposite that would occurred.

ROME’S FAILURE IN ARABIA.

The conversion of the tribes did not have the desired effect of fostering a Christian civilisation in the centre of the peninsula. Once he was established in Palestine, Al-Harit lost all influence over his former tribes of the Hedjaz. In the south of the peninsula, Yemen once again fell under Persian rule in 572. Ethiopia reestablished there a Christian dynasty around 525.

Furthermore, Byzantium’s Arab policy did not culminate in a significant influence of Christian civilisation in Arabia. Totally subject to immediate war aims, it amounted to nothing more than a temporary recruitment of clients that did not occasion any improvement on their part. Maintained by Byzantium’s subsidies, the Ghassanid princes never built a capital, but remained camping in tents, driving their flocks, leading a carefree life according to entirely pagan customs and living on the booty of their pillages. For these born quarrellers who were paid by the Byzantines to wage war on the detested enemy tribes, the Christian religion was only an opportunity for additional quarrels. Al-Harit’s adherence to Jacobite Monophysitism was a continual source of disagreement with the emperor, who was either Chalcedonian or Monothelite depending on the period.

Finally, relations between the Byzantines and the Ghassanids were always marred by mutual mistrust, which damaged to the end an alliance from which the Byzantines could have expected very great advantages, had they been less suspicious. The treaty was abruptly broken by the Byzantines in 581 when Emperor Maurice ordered the arrest of Al-Mundhir, Al-Harith’s son, which provoked an open revolt by his other sons who plundered Roman settlements on the borders of the desert. The dismantling of the Ghassanid kingdom occurred shortly afterward, to the great detriment of the sedentary populations along the Roman boundary who were no longer able to count on the authority of a supreme ruler to contain the Arab looters. The local sheikhs regained the independence that they had before the establishment of the supreme phylarchy. Fifteen chiefs shared the governance of the tribes among themselves and several of them defected to the Persians.

It is no exaggeration to say that Byzantium’s policy towards the Ghassanids and the Christian Arabs of Syria, of Palestine and of the Province of Arabia was one of the causes that contributed to the future success of Islam. In fact, it fuelled hatred among some of these Arabs against orthodox Christianity identified with the cause of the Empire and it bound them, through tactless measures of persecution, to a quarrelsome and debilitating Monophysitism.

JUDAISM, THE REAL WINNER OF THE PERSIAN-ROMAN RIVALRIES.

At the end of the 6th century, the Persian-Roman rivalry had left the Persians in a strong position. Behind them, however, lurked Judaism. Their traditional ally against the Byzantine Christians was firmly established in the Hedjaz. In fact, after the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 a.d., then under Emperor Hadrian, after the second Jewish War and the defeat of Bar Kokhba in 135, Jewish communities had begun to settle throughout Arabia, not only in ancient Teima, at the crossroads of the important caravan trails, but also on the way to Yemen, in Khaibar, with its Hebrew name, also in Yathrib, present-day Madinah, the geographical centre of the Hedjaz.

What about Mecca? Mecca, which is traditionally held to be an important stage on the Frankincense Route in the south of the Hedjaz, is absent from all the ancient maps until the time of Islam. No mention is made of it in Ptolemy’s Geography, in Hierocles’ Synecdemus – a Byzantium geographic text dated from the reign of Justinian (527-565), or in George of Chyprus’ geographic opuscule dated around 600.

Well settled in these oases, the Jews were very active throughout the 6th century, and under their authority, the main regions of the northern Hedjaz almost attained the high level of civilisation of the south of the peninsula. The Ghassanid barrier that separated Palestine from the Hedjaz and that made the position of the Jews so precarious disappeared in 584. Were it not for the Roman presence in Palestine, the Hedjaz would have appeared to be, after 584, like a veritable Israelite province, in continuity with the ancient Land of the ancestors.

Were a Jewish kingdom to be re-established in Jerusalem, the Hedjaz would quite naturally be englobed in a “Greater Palestine” equalling the Empire of Solomon itself!

This is precisely the immense hope that galvanised the Jews of Palestine and Arabia to the borders of Yemen, and all the Jews of the diaspora at the beginning of the 7th century.

NEITHER JEWS NOR NAZOREANS, “PERFECTS”!

A NEW RELIGIOUS LANGUAGE AT THE SERVICE OF AN ORIGINAL PLAN.

In 1957, our Father wrote in L’Ordre français that “ anyone who reads the Qur’an with common sense and honesty is irresistibly inclined to consider it as being imported from elsewhere [...]. The wisdom that it illustrates has matured elsewhere [other than in the Hedjaz].” This judgement was based on the work of a Dominican scholar, Fr. Théry, for whom the Qur’an was nothing other than an enterprise of Judaisation of the Arab tribes of the Hedjaz, in the context of what we have outlined above.

Brother Bruno’s studies, however, show that it involved much more than a simple attempt to convert the tribes to Judaism. “ In the same manner as Ronsard coined rich neologisms to enrich ‘Gaulish,’ the author of the Qur’an used the Hebrew language to give a religious language to the Arabs.” This vocabulary, drawn not only from biblical Hebrew, but also from the Aramaic used in Rabbinical literature, or even from Greek, is not employed arbitrarily. The author transposes the Hebrew language into Arabic with the precise aim of transferring for Arab usage the revelation contained in the Bible. He achieves this by divesting Isaac of the promises made to him by God to the benefit of Ishmael, the eponymous ancestor of the Arabs, the son of Hagar, the slave! It is a radical subversion, an unprecedented revolution that divests a fortiori Christians, who are children of God “ like Isaac ” (Ga 4:28) of the adoptive filiation, in favour of the descendants of Ishmael, the tribes of northern Arabia (Gn 21, 12-18.)

THE AUTHOR OF THE QUR’AN: A FORMER CHRISTIAN MONK?

The author is familiar with the Old Testament, but also with the New Testament, particularly with Saint Paul whose great emulator he is. The list of connections with the Apostle is impressive and leaves no doubt in this regard. Thus for our Father, after the publication of Volume 2 of Brother Bruno’s translation, there is no longer room for doubt. The author “ is an Arab, but he is heir to an immemorial religious tradition, Judaic in its essence and certainly Christian in its immediately previous form. Your sound exegesis underlines the admiration and the benevolence that the author of Sura III has for Christian monks and I do not hesitate to discover therein an indication and the simplest explanation for the extraordinary knowledge of the New Testament to which the Qur’an bears witness. Did this Arab not live in close contact with these monks? Was he not a student of theirs? A disciple even, or indeed a member of one of their communities?”

The Arabic alphabet was rarely used during the 6th century because it was, in fact, illegible. “ That explains therefore,” our Father continued, “ why the author of the Qur’an rendered this new alphabet “intelligible” by creating the Qur’anic writing for his people in order to initiate them to the Judaeo-Christian religion ingeniously modified to the benefit of Ishmael’s children. He had received the rudiments of this “ Writing” and of this “ Religion” in his home monastery. He completed the work of his monastic predecessors by giving the alphabet twenty-two letters, based on the model of the Syriac alphabet and following the same order, as indicated by the numeric values of the letters.”

These hypotheses, formulated by our Father on the basis of Brother Bruno’s scientific work, place us poles apart from the Muslim legend of Muhammed “receiving” the Qur’an as a “divine dictation.” We are, on the contrary, very close to these Arabs of the 7th century, all of whom were more or less Christianised through contact with the numerous monasteries of Syria and Arabia.

Archaeology has recently confirmed this hypothesis and reveals to us remarkable connections between the author of the Qur’an and the Christian communities of Arabia. For example, the pilgrimage that the author undertakes towards Jerusalem, similar to those of which the archaeologists find traces in Jerusalem, or even on Mount Nebo, which was the most well-known sanctuary of Arabia in Antiquity. Moreover, it is impossible not to notice a sometimes striking similarity between the motifs decorating the mosaics of Arabian sanctuaries (numerous scenes representing wine harvests, hunts, sheaves of wheat, cups of wine, etc.) and all the rules decreed by the author that aim to prohibit their use, for example, with regard to the Eucharistic banquet of the Christians.

The author intends to propose “ a way without quarrel,” that would be capable of putting an end to the confrontation that has opposed the Jews to the Nazoreans for six hundred years! It consists in a return to the original “perfect” religion, in Abraham and Ishmael. The war that was looming would give him the opportunity to carry out his programme.

THE WAR BETWEEN BYZANTIUM AND PERSIA:

THE EMERGENCE OF AN AUTONOMOUS ARAB GOVERNMENT.

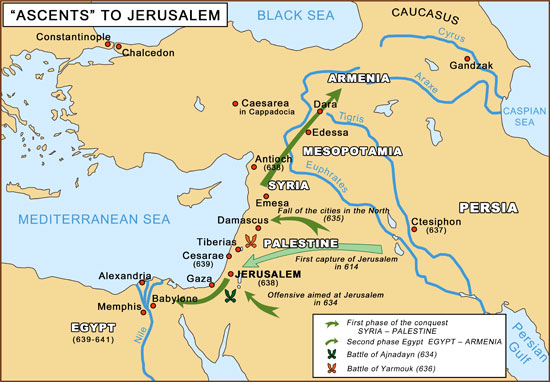

Byzantium and Persia were at war from 603 to 628. The victory would finally be won by Byzantium, but this almost thirty year-long conflict had the effect above all of exhausting the two belligerents and of leaving the field free to the “rising power” of the Arabs. The Byzantium Empire was plunged into anarchy since Emperor Maurice had been overthrown in 602 by Phocas, a centurion of the Byzantine army.

THE VICTORIES OF THE PERSIANS

Taking advantage of this waning of the Byzantium Empire, Chosroes, king of the Persians, captured the strategic position of Dara, in Mesopotamia, in 604. The Persians invaded Roman Armenia in 607, captured Caesarea in Cappadocia and advanced as far as the Bosphorus in 610. Phocas conducted the war in a disastrous manner and it was Heraclius, the son of the governor of Cartage, who overthrew him in 610. It was he who would conduct the Byzantine recovery until the decisive victory over Persia in 628.

In several campaigns, the Persians captured Antioch in 611, then they invaded Syria in 612. In 614, they took Jerusalem and led its Patriarch and inhabitants into captivity, after having seized the True Cross.

This fall of Jerusalem signals a beginning in the genesis of Islam. The decline of Byzantium’s power in favour of the Persians raised hopes among the Jews that they might one day re-establish their authority over the Holy City. In 613, the Jewish communities near Tiberias had opened the road to Caesarea, the administrative capital of Palestine, to the Persians. When they turned towards Jerusalem, the Jews apparently obtained from them the formal promise that the City would be placed under their control.

A “PILGRIMAGE” TO JERUSALEM.

The Jews, however, were not alone in backing the Persians. Bands of Saracens had also joined the invaders. An analysis of Sura II leads us to wonder whether their leader might not have been the author of the Qur’an who, although he assisted the Persians, was pursuing a specific goal.

Sura II is, in fact, an exhortation of a leader to his followers. He is seeking to strengthen their hearts for the “ascent to Jerusalem” where “ the Place of Abraham” (verse 125) is located, in other words, the site of the Temple of Jerusalem which, according to a constant tradition, was built “on Mount Moriah,” the very place of the sacrifice of Isaac (Gn 22:2.)

The exegesis of Sura II reveals the intention of the author: it was not to found a third religion, but to abolish Christianity and Judaism by restoring what he regarded as the one true Abrahamic tradition. The expression “ Abraham will re-establish the foundations of the Temple with Ishmael” (verse 127) is very representative of his intention of restoring the “ perfect” religion of Abraham in Jerusalem, as it is written, moreover, in black and white in verse 208: “ Enter into Salem!”

Thus, this Temple, “ the foundations” of which the author wanted to re-establish, is the Temple of Jerusalem and not the one in Mecca, as translators usually annotate. Sura II is again unambiguous when the author exhorts his followers: “ So go forth onto the path of the God and strengthen your hands until the ‘procession.’” (verse 195) The word “ procession,” ’at-tahlukat is the transcription from the Hebrew tahalûkhâh, which designates the ceremony that marked the dedication of the Ramparts of Jerusalem after the return from the Exile in Babylon, as we can read in the Book of Nehemiah 12:31.

Thus, like a new Nehemiah, our author resolved to celebrate a similar ceremony when the children of Ishmael would have won a victory over the Byzantine Christians who occupied the Holy City. The Creed of the author: “ Your God, the only God! No God except for Him, the Merciful, full of mercy,” (II, 163) is the transcription of the monotheist profession of faith that the Jews used from then on to oppose Christians as though the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit do not constitute one God, but three!

This grand design, however, was not achieved in 614. In fact, the alliance of the Persians with the Jews did not last long. In 617, the Persians were treating Christians considerately and forgetting all the promises made to the Jews. The Arabs suffered the same disgrace. Brother Bruno has hypothesised that the author and his followers retreated to Petra where he drew lessons from this first failure in Sura III.

He, however, used the retreat to better reinvigorate his followers, to whom he gave a law and whom he prepared to set out again on the road to Jerusalem, as we can read in Suras IV and V.

THE BELEAGUERED BYZANTIUM EMPIRE AND THE SUDDEN REVERSAL OF 622.

In the meantime, the Persians had captured Chalcedon in 615, from which they threatened Constantinople. Between 617 and 619, they conquered Egypt. This was a catastrophe for Constantinople that was dependent on the fertile plains of the Nile. It was thus deprived of its wheat supplies.

For six years, Heraclius reorganised the last provinces still under his control, rebuilt a strong army and decided to strike Persia at the very heart of its power by leading the warlike peoples of Armenia and the Caucasus against it. It was a resounding military operation that allowed the Byzantines to liberate Asia Minor and to penetrate into Armenia in 622, where they defeated the Persians. From there, in the spring of 623, Heraclius invaded Media Atropatene (present-day Azerbaijan), and he almost captured Chosroes in Gandzak.

Henceforth, the Byzantines had the advantage and obtained a definitive victory near Nineveh in 627. Peace was signed in 628. In 630, Heraclius entered Jerusalem as a triumphant victor with the True Cross.

THE CONSEQUENCES OF THE BYZANTINE

RECOVERY OF 622: THE DAWNING OF THE “ARAB ERA”

It would seem that this amazing victory of the Byzantines, who had suffered defeat after defeat for twenty years, had a profound impact among the Arabs.

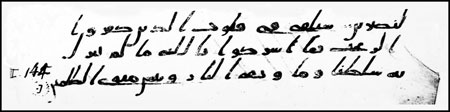

This is what we learn from a Greek inscription discovered on the ruins of the baths of Gadara, in Palestine. This inscription bears the date of “ the year 726 from the founding of the city,” i.e. the year 662-663 of our era. This date, however, is followed by another, as a complement: “ year 42 according to the Arabs.” It results from this that the year 622 a.d. marks the year 1 of this “Arab era”.

This inscription bears the sign of the cross at the beginning of its first line where we can read: “ In the days of the servant of God, Maawia, emir.” This shows that the God Whose servant the Emir Maawia declares himself to be, is the God of Christians!

This Arab era, which is not Muslim, begins with the taking of power in Iran by the Arabs, following the collapse of the Sassanid dynasty, after the Byzantine victory in 622. The Emir Maawia, the founder of the Umayyad dynasty bears an Aramaic name: it is not until the 9th century that the Muslim legend will “Arabise” his name as Mucâwîya and make him a companion of the prophet. In fact, he personifies the Christian Arabs of the East, for whom Greek was not an unknown language since the School of Athens, closed by Justinian I in 529, had emigrated to the Persian Empire. (according to Volker Popp, The Early History of Islam, Following Inscriptional and Numismatic Testimony, p. 37).

This archaeological research converges with the results of our scientific exegesis of the Qur’an, leading to surprising but solid conclusions that call into question events, i.e. the Hegira, which has been considered as marking the beginning of Islam in 622.

It is only later on, in Bagdad, that the massive political changes that followed this great victory of the Byzantines in 622 over the Persians received a “Muslim meaning.” In reality, a new era did begin: the period of self-government of the Christian Arabs.

“THE INVISIBLE CONQUEST”

Did the Arabs really emerge from Arabia brandishing the Qur’an in the name of Allah and his prophet Mohammed as is related in the history that was chronicled three centuries later by Muslim historians?

In reality, as Brother Bruno clearly demonstrated in an unpublished article on the Arab invasions, the “Muslim conquest” was instead a sort of “subversion” that spread from one already seditious province of the empire to the next.

THE END OF BYZANTINE DOMINATION

IN THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST.

After the victory, Armenia, Byzantine Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt were returned to Byzantium. Yet here is how our Father described the situation of Heraclius’ empire in 630: it “ was only seemingly favourable. The Greeks whose help had been sought against the Persians were just as detested by the populations of Syria and Egypt for their continually inflamed subtle religious dissensions. The entire ‘Monophysitic’ East, which accentuated, exaggerated the unity of the Divine Being of Christ, loathed as much the Byzantines who were faithful to the dogma of Chalcedon as it did the Persians who had completely fallen into Nestorianism [...]. The insufficiently manned garrisons under the command of a distant emperor, who himself was absorbed by the threat of the barbarians who were crossing the Danube and prowling the area surrounding Constantinople, were not in a comfortable position. The Persian Empire at the other end of the desert was no more than a pale shadow of its former greatness and might. The world was about to change dramatically.”

The pillaging Arabs were no longer impeded by the former federated Ghassanid and Lakhmid States, and they reappeared as soon as the war ended. In Syria, the collapse of the economic system of trading with the sedentary populations incited the nomads to engage simply in a conquest to assure a stable flow of commodities and foodstuffs for their subsistence.

The first evidence of this “Arab awakening,” to use our Father’s term, “ can be found in the Christmas homily of the Patriarch of Jerusalem, St. Sophronius in 634. He spoke of how it had been impossible to go in procession to Bethlehem the previous night because of the insecurity of the countryside.”

The first battles waged by the Arab bands against Heraclius’ armies seem to indicate that a veritable offensive took place against the Holy City, which was the first conquest of the Arabs in Palestine since, contrary to the generally accepted chronology, the fall of Gaza must be situated after the capture of Jerusalem. The rout of the Byzantines at Ajnadayn in 634, the fall of the Syrian cities of Emesa, Tiberias and Damascus from January to August 635, their evacuation when a new Byzantine army approached, then their reconquest after the Battle of Yarmouk in August 636; all these events would seem to have open the road of Jerusalem to the Arabs. From Antioch, Heraclius returned to Asia Minor and ordered that the True Cross be brought from Jerusalem to Constantinople.

In 638, St. Sophronius opened the gates of Jerusalem to the Arabs. The fall of the Holy City opened the coastal road to them and the capture of Gaza allowed them to pass into Egypt. The capture of Antioch in 638 and Caesarea in 639 completed the conquest of Syro-Palestine and involved the Arabs in the conquest of Byzantine Mesopotamia and Armenia.

Evidence shows that in Egypt, where the Arabs entered in 639, the invasion had not in the least been premeditated. The leader of the expedition, Amru adopted a very clever strategic plan, which could only have been indicated to him by local people. In fact, the Monophysites, who had been favoured during the Persian occupation, welcomed the invaders, informed them about the Byzantine troops and guided them through the Nile delta to the heartland of the country. The Arab invasion rapidly took on the nature of a Coptic revolution.

The case of Armenia is even more typical of the nature of the Arab invasion, which was more “subversive” than conquering. The Bedouins laid waste to the flat country but were unsuccessful before most of the forts and even suffered heavy losses to the Byzantines. It was the Armenians’ refusal to unite with the Church of Constantinople and to recognise the Council of Chalcedon, as Emperor Constans had ordered around 650 that led them to prefer the domination of the Arabs to that of the Empire. When the emperor intervened militarily in the country, he did not do so against the Arabs or against Islam, but against the rebellious Armenians and Monophysitism.

Let us stop following the traces of the Arab “conquerors” here. The two examples of Egypt and Armenia suffice to demonstrate that the Arabs only took advantage of the military weakening of the Byzantines and their religious divisions without seeking to impose an Islam which, as yet, did not exist.

“RESTORE THE FOUNDATIONS OF THE TEMPLE.”

Brother Bruno has shown that beginning in 634, Jerusalem was the objective of the Arab expeditions in Syro-Palestine. Does this reveal an intention that is linked to our exegesis of the Qur’an? We have seen that it begins with a pressing invitation made to the sons of Ishmael to ascend to Jerusalem, with the purpose of re-establishing the foundations of the “ devastated Temple” (II, 127). That took place in 614, according to our hypothesis, during the capture of Jerusalem by the Persians, with the assistance of the Jews and a faction of Saracens.

Did the Arabs undertake this task of re-establishing the “ foundations of the Temple” as early as 638? We have a short anonymous account that shows the Patriarch of Jerusalem, St. Sophronius, who died in 639, outraged to see a deacon of his clergy, a skilful marble mason, giving his remunerated assistance to the Arabs.

During the reign of Maawia (660-680), Anastasius the Sinaite, a monk in the Sinai, when passing through Jerusalem, witnessed the important works that were taking place on the esplanade of the Temple, opposite the Mount of Olives and echoed, in order to oppose it, the rumour that was spreading: the Arabs are rebuilding the Temple of God. A Frankish bishop, Arculf, during a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 670, described this edifice, which must have been situated on the site of the present-day Al-Aqsa mosque, as a “rather unsightly” building, the walls of which consisted of an assembly of simple boards, but with a capacity of around 3000 persons.

What is the religion of those who were thus working to restore the “ foundations of the Temple” on the esplanade of the ancient Jewish Temple that had been destroyed by Titus’ armies in 70 a.d.? The chronicles of that period contain no trace of the existence of Islam during the conquest and in the first decades of the occupation of the former Byzantine provinces, quite the contrary...

A CHRISTIAN “ARAB ERA”?

The first decades of the “ Arab era” depicts the conquerors as Christian sovereigns. In 660, Maawia to whom an assembly of Arab chiefs swore allegiance in Jerusalem, prayed at Golgotha, in the Garden of Gethsemane and at the tomb of the Blessed Virgin (Joachim Gnilka, Who Are the Christians of the Qur’an? p. 155). By establishing his capital in Damascus, Maawia put himself under the protection of a prophet, Saint John the Baptist, whose basilica sheltered his grave. The crypt that contained the head of the Baptist rivalled the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

Moreover, Maawia had coins struck with the effigy of St. John the Baptist with either a dove or a lamb. Other Arab coins struck with the Cross and dating from the same period depict the Arab chiefs as Christian sovereigns. Copper coins dating from the beginning of the Arab era were also minted with the Cross and represent the Arab chiefs as Christian sovereigns in the style of the Byzantines. Images of the head of St. John the Baptist or the Lamb of God can be found on certain coins.

Copper coins whether found in Palestine or in Syria, also stamped with the sign of the Cross and bearing the legend “SION” are a sign of the self-conception of Arab Christians at the time of the reign of Maawia. They saw themselves as heirs of the tradition of Israel.

Historians and archaeologists are obliged to acknowledge the absence of a real break between the Byzantine period and the so-called “Muslim” period. One of them even went so far as to speak of an “invisible conquest.” Certain mosaics uncovered in excavations have inscriptions that allow us to identify the bishops and to attest to the survival of Christian churches after what is commonly referred to as “the Muslim conquest.”

The excavations carried out in the localities of Rihab and Khirbat es Samra show, for example, that at the very time (634-635) when the Arabs occupied Bosra, the Metropolitan See of the Province of Arabia to which the two villages belong, the populations had begun to build several churches. “ If we take into account the time required to finish these constructions, we must conclude that the populations of these two villages continued to live quietly, as though unaware of the political upheavals [...].” (Michele Piccirillo, L’Arabie chrétienne, pp. 222-223)

Elsewhere, archaeological excavations reveal the building or restoration of churches long after the Arab conquest in the ancient Province of Arabia: in Rihab, Saint Sergius’church, built and ornamented with mosaics in 691; in Quwaysmah, the restoration of a mosaic dated in 717, etc.; up to the mosaic of the church of the Virgin Mary in Madaba, as late as 767!

THE HERESY OF THE ISHMAELITES

“THE CHRIST-JESUS, SON OF MARY”

The inscriptions that decorate a mosaic in the church of the Virgin Mary bear a touching testimony to the devotion of Madaba’s population for the Blessed Virgin “ holy and immaculate Queen,” “ virginal Mother of God” and for Our Lord, “ Whom She generated, Universal King, only Son of the only God.” They also express a sense of identity asserted by “ the people of this city of Madaba who love Christ.”

Fr. Piccirillo, in fact, points out that the wording, the meticulous precision of the qualifiers, and the firm affirmation of the divine and virginal Maternity of the Blessed Virgin mean that the people of Madaba “ are clearly on the side of the adherents of orthodoxy” (op. cit., p. 238).

Brother Bruno’s research demonstrate precisely that the author of the Qur’an disputes the idea that Christians have of the worship given to the Lord Jesus Christ and to His divine Mother; for example: “ Long ago, they apostatised, those who said: ‘Here is the God, he, the Christ, son of Mary,’ whereas Jesus said ‘O sons of Israel, serve the God, my Master and your Master.’” (V, 72)

The name “ son of Mary” is intended to supersede the name of “ Son of the Most High” (Lk 1:32). The author is also familiar with the Gospel of St. John, and he changes the words of Jesus “ my Father and your Father” (Jn 20:17) into “ my Master and your Master” (III, 51.) Like Saint Paul, the author also calls Jesus “ Christ”, but deprives Him of His kingship as Son of David and, therefore, of His “ messiahship” itself. For “ kingship over the Heavens and the earth and what they contain belongs to God” (V, 120.)

The antitrinitarian polemic shows through everywhere, beginning with Sura I, in which “ the God” receives the most beautiful of names: “ merciful,” “ master,” “ king,” but never that of Father, for he has no child.

THE SCHISM

The first dated non-Qur’anic historical evidence of this heresy and its subsequent schism is found in Jerusalem, on the esplanade of the Temple, inside the Dome of the Rock built during the reign of Abd al-Malik (685-705).

The plan and the construction of the Dome of the Rock places it within an ancient tradition of Byzantine architecture, represented by monuments situated in Ravenna, Italy, but also in Syria (Saint Simeon, in Bosra,) and by the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, the rotunda of which served as its model. The Dome of the Rock most likely formed, with the Al-Aqsa mosque, an architectural ensemble that imitated the original Constantinian style Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre. With what intention?

Under the cupola of the Dome is found the Rock that the Qur’an calls the maqâm, the “ place” of Abraham. It is the summit of the Mount of the Temple where, according to ancient tradition, Abraham ascended with his son Isaac, in order to offer him to God in sacrifice (Gn 22.2). This is where the Holy of Holies stood or the altar of holocausts of the ancient Temple.

In the Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre, the rock also outcrops in the very place of the Crucifixion, the burial and the Resurrection of Our Lord, which the Qur’an denies: “[...] they did not kill or crucify him, and that is why he came back to them [...].” (IV, 157)

More than one hundred inscriptions presently decorate the interior of the Dome of the Rock. Four among them, running along the interior arcades date, according to archaeologists, from the construction of the Dome. They constitute a veritable antitrinitarian profession of faith as evidenced by this passage that can be found in Sura IV, verse 171: “ O you, people of Scripture, do not pride yourself on your justice and say about the God only that which is in consonance with the law: Christ Jesus, son of Mary is only an oracle of the God.”

The word islâm is found in the last section of the inscription and is habitually taken as the manifestation of this new religion revealed to Mohammed. It is the phrase that we find in Sura 3, verse 19, which is usually translated: “ The (only true) religion for God is Islam.” The gloss that this translation requires is not in the text. In fact, the exegesis of this verse, interpreted together with that of other suras, indicates to us a different meaning that finds its fullest expression in such a place, where the Arabs think that they are going to recover the original perfection in Abraham and Ishmael.

In fact, the word islâm, “perfection” is derived from the root šlm, which is common to the Hebrew and Aramaic. It designates the “justice,” ’ad-dîn, with which Abraham is invested. It signifies the moral perfection that is required of the faithful in order to be God’s guest on the Holy Mountain, i.e., to worship Him. This is the perfection of the soul in peace with God, like Abraham who remains the model. “ Justice, in the eyes of God, is perfection.”

THE IMMENSE PRIDE OF A DISSIDENT.

About fifty years after the construction of the Dome of the Rock, between 743 and 745, St. John of Damascus devoted the last chapter of his Book of Heresies to the hundredth one, which he entitled “ The religion of the Ishmaelites.”

It was the first time that an ecclesiastical author mentioned the Qur’an and dealt with Muhammadanism. With scathing irony, St. John of Damascus denounced “ the seductive superstition of the Ismaelites, a prodrome of the Antichrist [...], who follow a false prophet named Mamed.” In an overview of their “ book,” which suffices to identify it with the Qur’an as we know it, St. John of Damascus shows that he had a thorough knowledge of this new heresy. Let us point out though that the terms “ Islam,” “ muslim,” and even “ Qur’an,” were unfamiliar to him, but he was already aware of the Muslim tradition since he held “ Mamed” to be the name of this false prophet.

Muḥammadun is repeated ten times in the inscriptions on the interior arcades of the Dome of the Rock. In the Qur’an, the word is repeated four times. Morphologically, it is a passive participle derived from the biblical root hmd, which means “ to desire, to covet.” Brother Bruno translates it by “ Beloved ”: Object of divine favours.

The term Muḥammadun appears for the first time in Verse 144 of the Sura III: “ A ‘beloved’ (muḥammadun) is only an oracle. The oracle who had preceded him was already weak. Even if he were to die, or if he were killed, would you retrace your steps? [...]” By transposing into Arabic the appellation ’îš ḥamudôt, “ the man of the predilections,” which the angel Gabriel used to address the prophet Daniel on behalf of Yahweh, it describes a man, the oracle of God.

If this word indubitably designates the author of the Qur’an, is it his proper name as St. John of Damascus already believed? According to Brother Bruno, this would be difficult to affirm, but what is important lies elsewhere. St. John of Damascus did not have at his disposition Brother Bruno’s scientific research that allowed our Father to perfectly understand the author’s systematic resolve “ to contradict Christ, to blaspheme Him and, finally to substitute himself for Him. Just as St. Paul, did not hesitate to identify himself with Christ, as a fervent disciple would, this religious genius and man of action of rare potency did likewise, but as a dissident.” (Afterword to Volume III of the Qur’an, p. 323)

As a result, the Holy Sacrifice is eliminated and animal sacrifices are restored, the Divine Sonship of Jesus is denied by crafty distortions of His authentic words and the historical fact of the Crucifixion is denied in order to withdraw Our Lord’s royal power by His exaltation on the Cross.

For the author proclaims himself to be the “ oracle” of the “ living God,” object of divine favour, coming after Christ Jesus and announced by Him.

CONCLUSION

That is how this heresy entered “ the history of religions through the back door,” our Father wrote. “ The testimony of St. John of Damascus is essential. It allows us to affirm that Islam began to spread among the Arabs as a new sect a good century after the alleged events of Mecca.”

What can be drawn from this brief historical overview of the dawning of the Qur’an during the first century of the “Arab era”? Several points emerge, all of which contradict the Muslim legend about the origins of Islam.

The heresy of the Ishmaelites germinated in a Christian breeding ground; this fact is abundantly proven not only by the most recent archaeological discoveries but by the exegesis of the Qur’an itself. We can see it slowly developing throughout the 7th century on the esplanade of the Temple in Jerusalem, the foundations of which the Arabs had restored, and on which they rebuilt the walls.

Yet, far from being a pure and simple return to the Temple of Herod, the “ Place of Abraham” marks the fact that the old quarrel between the Jews and the Christians has been transcended by restoring everything in the “ perfect” religion of Abraham and Ishmael.

This entire movement, however, took place under the domination of Christian Arab leaders, in a Christian context, at least until Abd al-Malik, at the turn of the 7th and 8th century. The Muslim legend precludes even supposing such a fact! We are far from Mecca, Mohammed, and the rapid and irresistible conquest of the ancient Byzantine East by the Qur’an.

Nevertheless, the testimony of St. John of Damascus tells us that a “ book” does indeed exist. He gives an overview of it and indicates that people already speak about a “ prophet called Mamed.”

Let our Father, Georges de Nantes, conclude this article himself:

“ St. John of Damascus [...] died peacefully in 749 in his monastic cell, honoured with the friendship of the caliph of Damascus. He, however, would be overthrown the following year and all the Umayyads assassinated.

“ A new Arabian history began in Baghdad [with the new Abbasid dynasty,] but this time it was entirely Muslim. The sect had conquered power; it would fabricate an incredible and fantastic past, as the whim took them, and the Occidentals never quibbled with them over their legends.”

It remains, therefore, to endeavour to continue distinguishing fact from fiction by doing a scientific work for the love of the Immaculate Heart of Mary and the salvation of souls!

Brother Michel-Marie du Cabeço.