The Qurʾān

Translation and Systematic Commentary

Volume I

PREFACE

Is it permissible to read the Qurʾān as a document from the past and seek to explain it with the rules of the historical and critical method that has long been employed in the study of the Bible? It is certain that no one has yet taken this liberty: “The historical and scriptural method, based on epigraphy and archaeology, has not yet been applied to the Qurʾān according to usual standards,” admitted Denise Masson by way of introduction to her own translation.●

What is the reason for such procrastination? Is it oversight, disinterest, or even contempt on the part of the academic world? Certainly not! Ever since Bonaparte’s expedition to Egypt, keen interest has been shown for Islamology in our old countries of Christendom. Almost two centuries later, this interest has not yet waned. The immense bibliography on the subject, rendered illustrious by the greatest names in biblical exegesis itself attests to the fact.

What then is the reason for the persistence of this lacuna? The answer is surprising in our times of hypercritical exigencies, but it is unquestionable: a certain dogmatism, the invariable formula of which can be read in all the best contemporary Islamic scholars who themselves inherited it from their predecessors: “The Qurʾān, the Sacred Book of the Muslims was passed on to the Prophet, the passive instrument of the Revelation, such as it is kept in heaven from all eternity, on the Guarded Tablet (Q 85:22). Thus, the Book that is presented to us is, according to the most constant Tradition, the replica of the heavenly architype, revealed by ʾAllāh, in the precise, literal form that has been passed down to us. It constitutes a miracle in itself.”● Under such circumstances, it is obvious that the text cannot be subject to any critical examination: “The Qurʾānic text is a sacrament: it conveys the grace to believe it. Its naissance was a miracle,” Jean Grosjean proclaims in the forward that he wrote to Denise Masson’s translation.●

To no avail might we object that the miracle itself could at least be subjected to a scientific debate by distinguishing the literary genres and searching for the sources in order to detect the original contribution of a divine revelation in the very heart of the human work: “Let us pay heed to Massignon,” Denise Masson adds, “‘the text of the Qurʾān presents itself as a supernatural dictation written down by the inspired Prophet. He is a simple messenger responsible for transmitting this deposit. He always considered its literary form as the sovereign proof of his personal prophetic inspiration, a miracle of style superior to all physical miracles.’”●

This dogma totally governs Islamology today as in the past, in Paris as in Cairo. It is upheld by the purest and most constant Muslim tradition. The value of this tradition must therefore be examined.

I. FATHER LAMMENS’ CRITIQUE

Not more than a century ago, around the time when the École biblique in Jerusalem was beginning to apply the critical method to the study of the Old and New Testaments, several researchers undertook painstaking and scholarly studies on the Muslim Tradition and soon discovered its secret, its fundamental law.

Composed of the Ḥadīṯ and the Sunnah, it is written down in books composed in the 9th century by authors whose method consists in ascending a series of “authorities,” isnād, or a chain of traditions, until they reach either the eyewitnesses of the 7th century events related in the Ḥadīṯ, or the authors of the legal maxims gathered in the Sunnah. The traditional biography of Muḥammad, the Sīrah, is itself nothing more than a collection of this sort.

The work of the Jesuit, Father Lammens, of Saint Joseph’s University in Beirut, shows at the beginning of the 20th century that the so-called “eyewitnesses,” the authorities of the Ḥadīṯ, are fictitious. The Sīrah has no historical basis other than the Qurʾān, of which it is nothing more than an imaginary elaboration: “Since the Tradition arises from the affirmations recorded in the Muslim’s Sacred Book, it does not provide a verification or complementary information as was previously thought, but an apocryphal elaboration. On the framework of the Qurʾānic text, the Ḥadīṯ elaborates its legends, merely inventing names for the actors depicted therein and spinning out the primitive theme. Its work is limited to these doublets, which are plenteous and exceed by far the activity of Christian authors of the Apocrypha.”●

The Jesuit scholar began by basing himself on the “insightful studies of Professor Goldziher”● who, prior to him, had brought to light “the profoundly tendentious nature of the Tradition.” He, however, had to admit that western Islamic scholars continued to give great importance to it as far as the Sīrah was concerned. “To be convinced of this, it suffices to glance through the most recent biographies of Muḥammad. They, like the old accounts, are in fact derived from the Ḥadīṯ. What has been the outcome of such patient and scholarly research? Mr. Nöldeke, a worthy Semitist, declared that, for his part, he had renounced exploring the mystery that envelops the personality of Muḥammad.”●

That is why Father Lammens adopts Goldziher’s viewpoint and pursues the inquiry undertaken by this Hungarian scholar on the historical value of the Tradition. The conclusions are firm and represent a considerable advance over Goldziher’s. The latter had shown the “tendentious character” of the Tradition. Lammens shows its “apocryphal” nature. In fact, like Jewish and Christian pseudepigrapha, the accounts of the Muslim Tradition are legends that have no foundations other than previous writings, the “sūrahs” of the “Qurʾān” that they paraphrase. Here is the proof:

MUḤAMMAD’S PRE-EXISTENCE

“The pre-existence of Muḥammad’s soul is a favourite dogma of the Tradition that finds a ‘scriptural’ foundation for it in the texts in which we can read: ‘We have sent you a light.’ This theme was elaborated later on and applied to the person of the Prophet. Thus his body emitted light waves so that it could become visible in the thickest darkness. One night, this light is purported to have allowed ʿĀyša to find a lost pin…” The theme undergoes endless developments in the Sīrah, but it does not furnish any historical complement independent of the Qurʾānic source.●

THE POOR ORPHAN

Then follows the “incarnated” life of Muḥammad, the main stages of which are his youth, his preaching in Mecca and the Medinese period. All the superabundant information that the Sīrah provides on Muḥammad’s youth amounts to variations on a single theme: the orphan. Why? Because the only documentary basis for these elaborations is provided by these words: “We found you, poor, orphaned, without a family.” (Q 93)

We will show how Lammens, abiding by the whole Tradition while at the same time criticising it, incorrectly translates this verse. For the moment, this is of little import. Let us accept his translation with certain reservations. Understood in the way we have just quoted, “these words provide the framework for a veritable Evangelium infantiæ Muhameti. There is nothing that permits verification of the exactitude of the tale built on these unsubstantial facts, in which he passes through all the hardships experienced by Arab orphans. The imagination of the traditionalists supply them.”●

“For future historians of Muḥammad, if this observation is well-founded, it eliminates in one stroke thousands of pages of whimsical documents; it makes the first thirty years of the life of one of the most extraordinary men of the East fit on one single line.”●

THE PERSECUTED PROPHET

In contrast, as soon as Muḥammad began to preach, we can easily understand how people must have begun to speak about him. The tradition should relate elements of the “impressions gleaned” at that moment on the extraordinary personality that suddenly revealed itself and that no one had yet suspected. This is not the case. All the scenes of the persecutions endured by Muḥammad in Mecca that are reported in the Sīrah are only a purely artificial elaboration of the facts provided by the Qurʾān.

Among these facts, “the Tradition discovered a veritable persecution; in its view, this period becomes the age of the Islamite catacombs. In the entire Qurʾān, the very prudent Muḥammad only pronounced two proper names of men. It is this circumstance that made Abū Lahab Lahab (Q 111:1) the archetype of the persecutor, the moving spirit of every conspiracy against nascent Islam.”●

The same applies to all the traditional themes that constitute the basis of the accounts of the Sīrah for this period. “In the Ḥadīṯ, the Prophet begins by preaching to his family; yet another fact provided by the Qurʾān (Q 26:214,) ‘Evangelise your next of kin.’ For visits to Tā’if and the fairs close to Mecca, there is the text: ‘Preach in the mother of Cities (Mecca) and in its vicinity.’ (Q 42:7) The Tradition knows in great detail the objections raised against Muḥammad. They form the elaboration of those that the Qurʾān addresses to the prophets, his predecessors, and to himself. Very seriously, the Sīrah claims to inform us about the characteristics of Quraishite polytheism. In this instance, we would willingly give it credence: the Meccan companions of Muḥammad should have known their ancient religion. Yet, how can our scepticism not be aroused when we see it confining itself to paraphrasing the indications provided by the Qurʾān (Q 8:35)? The loss of Al Kalbi’s Kitāb al-ʾAṣnām remains regrettable. Was this book, however, really original? I mean, was it independent of the Qurʾān? The fragments retained with their mythology that is so clearly Qurʾānic do not allow us to reply in the affirmative. This reflection should serve to moderate our regrets.

“What must be thought of the infanticide practiced by the Arabs” continues Lammens, “and especially their custom of burying girls? The Tradition confirms it, but the cases quoted by it are few in number, and generally anonymous […]. Once again, we suspect that the Tradition interpreted the Qurʾānic query in a material sense (Q 16:59).”●

In the end, Lammens admits the existence of a vague oral tradition at the beginning of ‘the Hijrah.’ If it had survived, this alternative channel would have provided a second source and would permit a precious means of verifying the primary source, which is the Qurʾānic text. However, “from the outset, it was distorted by being violently adapted to the Qurʾān, which had become the sole rule of sacred and profane knowledge. When the historical figure of the Master had to be established, the most ancient traditionalists began by opening this book. If they were concerned with the testimony of contemporaries, it was in order to make them coherent, to align them with the assertions of the ‘Book of ʾAllāh.’ For the oral tradition of the 1st century of the Hijrah, the narrow framework of the Qurʾān became its Procrustean bed.”●

As for pre-Islamic poetry, which should also provide us with a precious means of cross-checking, it is reduced to a sort of “apocrypha.” This is because we know it only through the Sīrah, which “confined itself to retaining only the excerpts in which it was believed that the confirmation of its theories could be found. The rest either was not worth retaining or had to be expurgated as blasphemous. In this respect, Ibn Hišām’s methods and his revealing admissions can serve as a demonstration.”●

THE WARLORD

Father Lammens even believed that the historicity of the details handed down concerning the great military feats of Islam: Badr, Taboūk, Ḥonain, had to be abandoned. They all derive from short and confused allusions from the Qurʾān, “without adding anything essential.” Everywhere, the Tradition, “in keeping with its usual method, added or invented proper names. This literary device gives life to the anonymous declarations of the Qurʾān. It is a factitious life when we reflect on the absence of historical meaning that distinguishes the Tradition.●

THE PATRIARCH

All the efforts of the Tradition to endow Muḥammad with worthy descendants derives from the fact that the Qurʾān (Q 13:38) gives numerous descendants as being characteristic of prophets: “These childish devices give a total of twelve children, eight of whom are boys. It is the triumph of sentimental logic!”●

THE SAINT

As for the voluminous descriptions of the portrait of Muḥammad who is called samaʾil, ḥalq ʾan-nabi, ḥilia, sifa, their purpose is to provide us with a detailed representation of his physical appearance, his moral character, his habits and his likings. The method that governs its elaboration is thinly disguised: “When we see the Tradition beginning to establish its thesis, i.e., Muḥammad’s moral and physical perfections, then confirming it all by quoting the sacred text, the real order of the premises in this syllogism might go unnoticed by uninitiated readers. Let us not forget, however, that in this demonstration, the Qurʾān forms the main argument. ‘The Prophet’s way of life?’ exclaims ʿĀyša, ‘Why, it is found in the Qurʾān.’ One starts with the Qurʾān, while giving the impression of ending with it.”●

For example, the Qurʾān says: “We made all of Muḥammad’s predecessors mortals, feeling the urge to eat.” Hence the insatiable appetite that the Tradition attributes to the Prophet, in particular his keen taste for honey: “In its zeal, the Tradition wanted to draw on this divine justification, without wondering whether its realism had not exceeded the intention.”●

Father Lammens who was really the first to see through the “hoax,” implacably exploited his discovery at the expense of all the important traditional themes concerning Muḥammad, “torchlight,” ẖātam, “seal” of the Prophets, ʾummayun, “illiterate” which, in the opinion of “traditionalist exegetes,” means his repulsion for poetry. This is accepted by the whole tradition following Ibn Hišām in whose eyes this illiteracy of Muḥammad constitutes the irrefutable “proof” of the truly “inspired,” miraculous nature of the Qurʾān. So that no one be unaware of the fact, it is embellished by a host of accounts in which Muḥammad seems totally unfamiliar with poetic rhythm, incapable of reciting a single verse without destroying its prosodic metre. Here Lammens subtly points out that “the alleged witnesses of these scenes rashly recall the verses of the Qurʾān that attest the Master’s poetic ignorance. It is impossible to betray oneself with greater ingenuity.”● No, “the traditionalists did not begin by eliciting the memories of survivors of the heroic age, but rather by opening the Book of ʾAllāh in order to discover therein what they desired to see in it, even if it meant adapting more or less authentic pieces of information to their biases, or even inventing them.”●

“Thus when the Islamic Tradition claims to be an independent source of information, the result of a vast inquiry organised by contemporaries on the life of the Arab Prophet, we can […] regard it as one of the greatest historical hoaxes the memory has been conserved in the annals of literary history. If the illusion has been able to persist for so long both within and without Islam, it must be attributed to the faulty critical apparatus, to the apparent naivety of the authorities cited in support of it, to the ingenuity in research, to the implacable logic in the error to which this enormous compilation bears witness.”●

It is therefore no longer possible “to present Islam as a religion born in the broad daylight of history”● contrary to “Renan’s rash assertions” according to which “Islam was born in the thick of history; its roots are apparent. The life of its founder is as well known to us as are the lives of the Reformers of the 16th century. We are able to follow the fluctuations of his thought, his contradictions and his weaknesses.”●

This is inconceivable! “It is true,” our Jesuit indulgently observed, “that the author of the Histoire des langues sémitiques was rather unfamiliar with Arabic; he had never explored the maze of the ḥadīṯ. Yet, who required him to express his opinion on their worth? Has not the liberty of his judgement been fettered by his rationalist prejudice.●

This is only too certain: the same prejudices that led him in his study on Jesus and Saint Paul to a very unscientific negative bias, led him to this gullibility that is still today, by an inexplicable perseverance in error, the credulity of all the authors of “scholarly” biographies on Muḥammad. For the scientific truth established 75 years ago by Father Lammens, forgotten since then, yet never refuted because it is irrefutable, compels us to claim dispassionately:

The “Prophet Muḥammad,” is a character created ex nihilo by Arabic literature. This creation appeared 140 years after the presumed death of the hypothetical character to whom it claims to refer with a “noble zeal” that “dates back to the great expansion of Arab imperialism under the Omayyads. Contemporary with the conception of Islam as a world religion, it was mainly the work of the Mawālīs or neophytes of foreign origin, the authors of the whole scientific movement within Muslim society.”●

The consequence was immediately perceived by the contemporaries of the courageous Jesuit. René Aigrain, in the article Arabie that he contributed to the Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques, concludes: “In these conditions, we can no longer deal with the history of Muḥammad by using, as several of his biographers do, the Sīrah as a basis.”● Published from 1922 to 1924, Aigrain’s article is a complete encyclopaedia on the question of Christian origins in Arabia, supported by a rigorous critical analysis of the positive data known at the time. Nevertheless, when it came to Islam, the author abandons such a fruitful point of view, simply reverting to the use of data that is considered to be traditional, immediately adding to the remark quoted above: “This does not mean that we must retain nothing from it, which would make it absolutely impossible for us to know the life of the Prophet.”

What an admission that is! It means that even outside the Sīrah there is not one single positive fact that attests at least to Muḥammad’s historical existence. That is why, when Father Lammens passed away, the Jesuits of Beirut put his works under seal, and since then it has been a law of Islamology to ignore his discovery, to continue to pretend to believe in the tale of A Thousand and One Nights: “Since this is the documentary material available to us,” Gaudefroy-Demombynes writes, “two extreme attitudes are in fact possible. One consists, for the European scholar, in translating into his language the accounts of the apologetic biography such as it was gradually put together in the Muslim world through the evolutions of the Tradition and piety. The other attitude which, in fact, has never been adopted because it would result in a renunciation, would consist in accepting only those things, the veracity of which can be established, that is to say, almost nothing.”● For his part, Mr. Gaudefroy-Demombynes declared that he would adopt the first solution, even if it meant “appearing naïve in the eyes of certain people.” Such fear is unfounded since in doing so, he is only complying with what has been the mandatory approach in both Western and Eastern Islamology for more than a thousand years.

For our part, we choose the opposite attitude, firmly resolved “to accept only those things, the veracity of which can be established” scientifically: “almost nothing”? Less than nothing? Absolutely nothing!

A MILESTONE HAS BEEN REACHED.

ONE SINGLE SOURCE, THE QURʾĀN.

In order to justify his choice, Demombynes endeavours to play down the significance of Father Lammens’ criticism: “The differences and contradictions that appear between the ḥadīṯ explain the mistrust that some historians like Father Lammens showed towards them.” We have just seen that it is not a question of ‘mistrust,’ nor of ‘differences’ and ‘contradictions’: Father Lammens positively demonstrates that the ḥadīṯ are nothing but pure inventions embroidered on the framework of the Qurʾānic text. This is done in such a way that “the writing of the Sīrah is not derived from two parallel and independent sources, mutually complementing and verifying one another, but from a single one, the Qurʾān, slavishly interpreted and developed by the Tradition following preconceived ideas […]. At the beginning of the 2nd century of the Hijrah, when the outline of the Sīrah was established, the writers tackled the sūrahs of the Qurʾān, attempting to specify the meaning, to put everywhere dates and proper names. The product of this exegesis, carried out haphazardly, is that the Sīrah remains to be written, just as the historical Muḥammad remains to be discovered.”● How can this be done? By replacing the fanciful exegesis of the Tradition by a scientific exegesis.

“I have always sincerely admired the heroism of the translators of the Qurʾān. A good version presupposes a thorough knowledge of the Sīrah. Since the Sīrah is derived in the final resort from the Qurʾān, one is caught in a vicious circle!” This observation of Father Lammens’ alone, reduces Régis Blachère’s work● to nothing, since it is a version derived from a virtually comprehensive knowledge of the Sīrah. It is an unrivalled monument upon which Denise Masson’s translation cited above is entirely dependent.

How then can we break out of this vicious circle? By boldly moving forward on the road opened by Father Lammens, following the method that his discovery prescribes.

ONE SINGLE METHOD

This method consists in rejecting the “Tradition” in its totality. Father Lammens recommended this, but he never dared to go so far. He argued: “The Tradition nevertheless retains a sui generis value, since the scientific exegesis of the Qurʾān has yet to be created.” Why had he himself not undertaken this very urgent and necessary creation? Without it, his entire work comes to the same dead-end as that of Nöldeke and Demombynes.

Readers may have noticed above that Father Lammens quotes a passage from the Qurʾān that served as a veiled source for the Sīrah, which destroys the claim that this compilation might reveal something new, while at the same time he surreptitiously introduces in parenthesis, a piece of information taken from the Sīrah! “Preach in the mother of Cities (Mecca) and in its vicinity.” The name of the ‘City’ in question is not found in the text. It is the “haphazard” exegesis of the Sīrah that indicates “Mecca” here. Why does Lammens follow suit?

The same applies to the imprecations of Sūrah 111 against Abū Lahab. Nowhere does the text say that he is Muḥammad’s uncle. Lammens, however, accepts it on the strength of the Tradition.

What inconsistency! Such a lack of logic explains why the “enormous” undertakings of this “tireless worker, unfailingly faithful to his vocation as an Islamic scholar, honest in his research, fair in his judgements,”● remained fruitless. After the magnificent article outlining a research programme that we have quoted at length, he endeavoured to prepare a life of Muḥammad. Several isolated chapters were published in separate articles.● The mere reading of their titles shows how far we have strayed from the revolution that the critical conclusions of Qoran et Tradition demanded.●

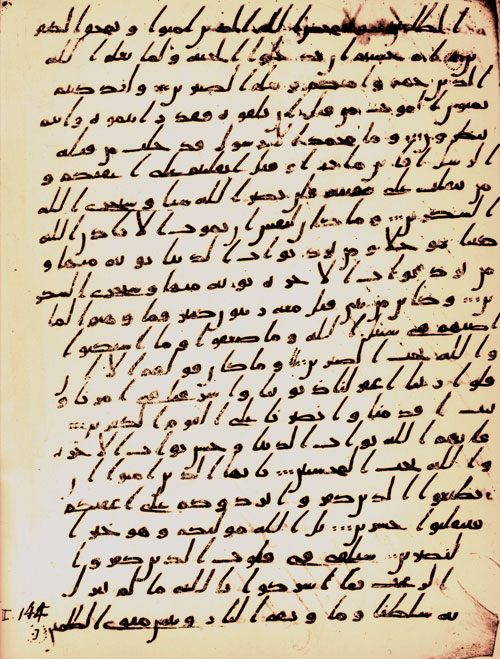

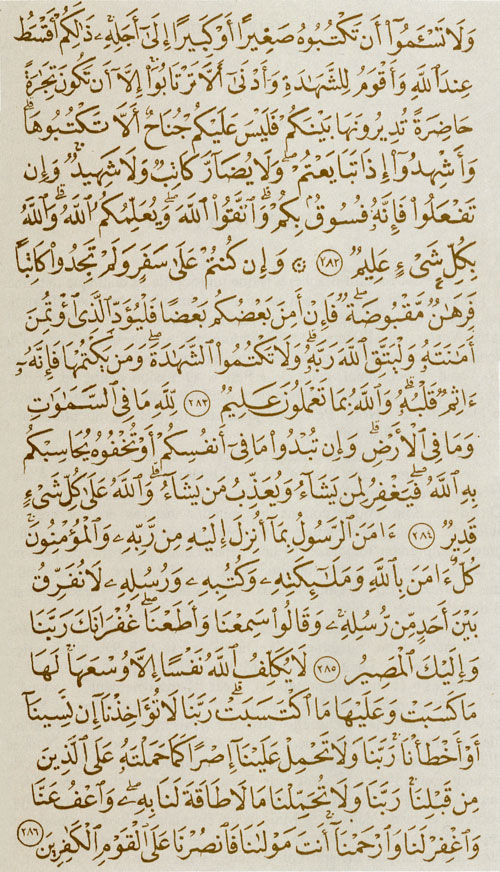

This folio of the manuscript “Arabic 328” (Figure 1) from the National Library in Paris, the verso of which is reproduced here, contains the end of Sūrah 2, starting from the end of verse 275. Critics generally recognise it to be the most ancient manuscript – some do not hesitate to place it in the 7th century. The origin of this Qurʾānic fragment remains unknown. Written in large, thick letters, although regular, and traced by a steady hand with brown ink on parchment, in a way similar to the one used on contemporary Egyptian papyri (7th century,) it does not contain the slightest variant with the “canonical” text still in use today (Figure 2).

The only difference lies in the absence of diacritics and vocalisation: solely consonantal, the text lacks the dots that differentiate the consonants and indicate the vowels, as well as all other signs that facilitate reading. The lines are filled without attention being paid to word divisions. They sometime end on the following line. Verses are separated by two rows of dots one on top of the other.

Hence, Lammens does not read the Qurʾān, but the traditional version given by the Arab annalists, even if it means expressing scepticism coupled with caustic irony, something that would seem unwarranted and insulting in the eyes of Muslims, without making the slightest progress in the search of the truth.

Today, going to the opposite extreme, which is just as devoid of a scientific basis, Qurʾānic scholars have an obsequious faith in the Tradition. The result, however, is the same: an impenetrable veil continues to conceal the true origins of Islam.

II. FATHER THÉRY’S INTUITION

Fifty years after Lammens, someone nevertheless did penetrate this veil with a new light. Although he remains the major absentee from all bibliographies over the last thirty years, Father Théry, a Dominican, must be considered the founder of “the scientific exegesis” of the Qurʾān, which had been the object of the desire of his Jesuit predecessor.● It is certain that the anonymous and private nature of the publication, intended to avoid exposing the religious and the priests working in Islamic lands to terrible reprisals, harmed his work. If it had been published under the true name of the author, a reputed medievalist in the scientific research community, it probably would not have enjoyed a more favourable reception by Islamic scholars, but it would have forced them to debate openly. Feigning ignorance of Hanna Zakarias’ identity which, very soon was no longer a secret for anyone, they could safely brand him “confidentially, as a bluffer and an ignoramus; contempt for the author obviously reflected on his work.”●

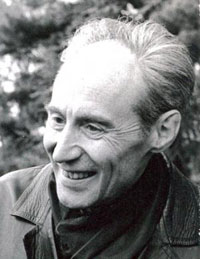

Thus, everything would undoubtedly have remained unknown to the public if Father Georges de Nantes had not immediately reviewed the first two volumes in a series of articles. Their impact broke the concerted silence of the Islamic scholars and, despite them,● a debate ensued.● Father de Nantes is not an Islamic scholar. As a theologian, though, he was well aware of the modern requirements of scientific criticism, he was able to take the full measure of the novelty. For the first time, someone had broken with “the millenary candour of East and West” towards Islam, and he had had “the freedom of mind to read the Qurʾān as a document of the past and to seek to explain it by the simplest laws of the historical method long in use within Catholicism itself for the study of the Bible.”● It is an event “capable of modifying all our forecasts on the future of Islam.” Father de Nantes noted this with a penetration that compelled the admiration of Father Théry himself: “You have expressed my thought very, very accurately; you have drawn conclusions from it that I had barely perceived.” He wrote this to Father de Nantes even before making his true identity known to him.●

“The Qurʾān is the authentic document of the origins of Islam, just as the Bible is that of the Jewish and Christian religions,” wrote Father Georges de Nantes. “It is in accordance with perfect historical method to study these books as closely as possible in order to find in them, rather than in any later tradition, the truth concerning the origins of these religions.”● The first question to be asked is that of the author and his sources, for “it would be extraordinary that an Arab civilisation could have appeared in the 7th century entirely based on the Qurʾān, a Holy Book, effortlessly sprung forth from the mind of an illiterate mystic in the sands of the desert.”●

To this preliminary question, Father Théry replied with “a hypothesis […] that is truly admirable in its simplicity, as are all brilliant hypotheses.”●

THE AUTHOR, CREATOR OF A LANGUAGE

“Anyone who reads the Qurʾān with common sense and honesty is irresistibly inclined to consider it as being imported from elsewhere… The wisdom that it illustrates has matured elsewhere.”● Who is the author of the Qurʾān?

He is a scholar come from elsewhere”● who “created the religious terminology of the Arabic language.”● This is the inspired intuition that occurred to Father Théry forty years ago while reading a translation of the Qurʾān by Montet. “It was a complete vocabulary,” Father de Nantes explained. “In the same manner as Ronsard coined rich neologisms to enrich ‘Gaulish,’ the author of the Qurʾān used the Hebrew language to give a religious vocabulary to the Arabs.”●

How is it that no one had thought about this before Father Théry? For all Qurʾānic scholars are aware of the fact: unlike the Hebrew Pentateuch the genesis of which can be established, the Arabic Qurʾān has no literary antecedent. This is precisely the reason why it constituted an almost insoluble enigma, a miracle, in the eyes of the Iraqi ‘exegetes’ of the 9th century, the creators of Arabic literature and keen translators of the Greek philosophers. “They compensated for their ignorance by the outpourings of their unfettered imagination. Since they did not know the direct meaning of their venerable texts and were unable to verify and detect the imposture […], the original meaning was lost as great efforts of imagination were expended to replace it by a different traditional but totally legendary meaning.”●

Literally, the Qurʾān seems to be an aerolite that has fallen from the sky: “In the history of the Ḥiḏjāz, it appears as a great, beautiful text that has been mutilated, dislocated and congealed. It has no predecessor nor worthy successor. For the love poetry and the satires of the period, which perhaps date from the pre-Islamic era, do not at all surpass the level of what an uneducated Tuareg tribe possesses in its tradition, and they are disproportionate to the lyricism and the elevation of the Qurʾān in the least of its praises to God. Compared to the Qurʾān, the writings subsequent to it, chiefly the Sīrah, are no more than stupid infantile prattle. The disorder, implausibility and coarseness of their legends on the life of the Prophet marvellously highlights by contrast the elaboration and the strength of the Qurʾān, this erratic block that appeared in the Arab tradition. It makes one think of that fleet of armoured vehicles that the Israeli found dispersed in the Sinai Desert last year! They did not come from Egyptians factories or minds!”●

HEBRAIC SOURCES

The study of the Qurʾān’s vocabulary incites us to compare it to the Hebrew bible and to the rabbinical midrashim. For Zakarias, who refers to it as the Corab, it seems to be, for the most part, nothing more than a pure and simple explanatory translation of the Bible, the “Book” par excellence, the Hebrew “Qurʾān.” The Corab, Father Théry writes, is “the Bible itself explained to the Arabs:● the story of Adam, Noah, Abraham, Lot, Joseph, Moses, etc.

There is, however, a remnant, apparently woven from allusions to events contemporaneous with the author himself. It bears witness to the pristine, original fact, which is irreducible to any ancient or new parallel, and which it would suffice to decipher to have the key to the origins of Islam. Herein has lain, for 1300 years, the whole difficulty. This does not deter Zakarias. He gives a name to this remnant: the Acts of Islam, “the psychological, religious and bellicose log book of a Jewish rabbi contending with Arab idolaters.”● Just as the Acts of the Apostles relate to us the beginnings of the Church after Our Lord’s Ascension, the Qurʾān, in its other part, which is easily distinguished from the biblical and midrashic accounts, contains the authentic and sincere chronicle of the origins of Islam.

It is the history of a Jew from Mecca who “preaches the religion of Israel to polytheistic Arabs with the intention of converting them to Judism.”● Now among the rich Meccan merchants who are listening to him, he soon singles out Muḥammad to whom he tells the story of Moses in order to persuade him to become a new Moses, the Moses of Mecca. Muḥammad, probably influenced by his wife, the rich widow Ḵẖadīḏja, undoubtedly a Jew, does in fact convert and during the day begins to recite to his compatriots the lessons learned at night in the synagogue from his master, the rabbi. This is how “a Jew adapted Jewish stories and translated them into Arabic. The Arabs imagined that ʾAllāh was speaking to them, the Arabs.”● This mystification has lasted for 13 centuries, guffaws Hanna Zakarias.

It must be acknowledged that when he reaches this point, Father Théry does not act decisively, any more than Father Lammens had, failing to carry out the revolution that his initial idea would have required: he does not read the original Qurʾān, but the accepted translation, which we know to be entirely derived from the Sīrah. Even if he modifies the scenario, his often facetious ingenuity which, as in the case of Father Lammens, sometimes degenerates into gratuitous insults to Muslims, must not mislead us: this entire reconstitution is fabricated from elements furnished by the Sīrah, firstly, the dates and proper names. After having got out of the rut for a moment during the study of the “Corab,” we slide back into it, caught in the vicious circle that Lammens denounces.

III. FATHER DE NANTES’ METHOD

How can we get out of this circle in order to learn about the origins of the Islam to which this book bears witness? “It should not be too considerable a task to analyse the Qurʾān,” Father Georges de Nantes points out, “since it is definitely the work of a single author and was written over a thirty year period, whereas the Bible is the written expression of a religious inspiration that affected an entire people during a millennium and more.”● This is how Father de Nantes, after having discerned that the aforementioned author was undoubtedly a great religious soul, breaks with the polemical acrimony of his predecessors, formulates the full magnitude of the scientific problem in a perfectly irenic tone.

A “DEFECTIVE”TEXT

In fact, long ago “scholars noticed the fixity and the unity of the Qurʾānic text. While all that is first spoken in the ears of simple men and entrusted to their memory comes to us in multiple documents diverging to infinity, the Qurʾān, after thirty years of a supposed oral tradition is a unique, immutable text, without any aberrant traditions. Only a few faulty lessons, a few minor uncertainties have been detected. Moreover, the schismatics of the first generations, the Alids in particular, contested the authenticity of the text compiled by Uthmān but were never able to restore, or even invent these pericopes that their enemy had purportedly rejected! They were only able to add here and there the name of their revered Ali in a text where he obviously had no place. Mr. Hanna Zakarias alone logically interpreted this implausible poverty, this lack of imprecision, this total absence of apocryphal literature, as the striking demonstration of the permanent inability of the nomads of the Ḥiḏjāz to compose a single sūrah comparable to the precious written legacy of a scholar from elsewhere. Give a watch to Pygmies and come back a hundred years later; the watch may be broken or disassembled, but you will not find another one that looks like it! In fact, the author of the Qurʾān liked to defy the Arabs to present a sūrah similar to his own, knowing how much plagiarism was beyond the capacity of his listeners!”●

Did they even know how to write? We are not sure at all that they did: “At the beginning of the 6th century, northern Arabia had a writing derived from the cursive calligraphy used three centuries earlier by the Nabateans of Petra,” Blachère explains. He hastens, however, to admit that this system is not even attested in a form that we can affirm to be common and familiar, but only “under a hieratic aspect, in two inscriptions placed in shrines, one (Greek-Syriac-Arabic) in Zabad (Aleppo region), dated 512, the other (Greek-Arabic) in Harran (south-east of Damascus) dated 568.”● Is that all? Yes, and it is not an indication of a very widespread use of this writing, the ancestor of the “Kufic script” that would later flourish in Iraq, and which, at that time, “executed by stone carvers” presented a “stiff and angular” appearance with a scriptio defectiva. Not only does this scripture not contain short vowels but certain consonants that are distinguished one from the other today by the use of diacritic dots have the same identical symbol. For example, the letters b, t, th, n and y; the consonants q and f; the consonants j and hard h, etc.

The Qurʾān was written in this “defective” form, or at least, from the angle of critical analysis this is where we must begin, since “the ‘ḥiḏjāzi’ Qurʾāns of a very archaic type, such as those of Paris Nos. 326 and 328, have no brief vowels. It is true that No. 336, also conserved in Paris, is partially vocalised, but it seems that they were added later. Similarly, many ‘Kufic’ Qurʾāns are vowelless or give the impression of vowels having been inserted subsequently.”●

The Qurʾān thus reduced to its most primitive form, is the only literary document in Arabic that Islam has ever possessed from which the history of its own origin can be derived. “Western scholars who work in the shadow of the University Al-Azhar in Cairo look for traces of pre-Islamic religious literature; let them sift the sand well, they will find nothing in it!”●

Who, then, will provide us with the lexicon and grammar necessary to decipher this meteorite fallen from the sky? What is commonly called “pre-Islamic poetry” can obviously be of no help to us since it is passed down to us by the Sīrah, “for its own ends,” as Lammens says. Without entering into the much debated question of the problematic existence of pre-Islamic poetry, we consider this poetry, in its present form, as post-Islamic. In terms of a rigorous critical method, it cannot provide us with an antecedent.

We really have to start from nothing, as the Muslim “exegetes” themselves did. Yet, Father Georges de Nantes, following Zakarias, posits in principle that “our modern science of religions and our instruments of textual criticism place us in an even better position to analyse and penetrate this text than the first Muslims themselves who were illiterate, recent converts to an immense religious system, and who were obviously overwhelmed by the exceptional erudition of their converter.”●

In fact, the only instruments available to these first commentators were the ambient spoken language on the one hand, and on the other the documents of non-Muslim literature, mainly Jewish, to which they had extensive recourse. We are less well-documented than them on the spoken language although, at that time, several generations after the events, it is probable that the language had undergone a notable evolution, liable to have already induced them into many contradictions. On the other hand, we benefit from an overwhelming superiority as far as Jewish and Christian sources are concerned. It was Father Théry's brilliant contribution to have understood that it was necessary to begin the investigation by comparing the Qurʾān to the Bible.

THE QURʾĀN BY THE QURʾĀN

Father Théry had indicated the way forward. Does that mean that this is the path that he himself followed? Father Georges de Nantes believed so at first: “Creator of powerful hypotheses,” he affirmed in his first article, “Hanna Zakarias is also a very great scholar. He succeeds in solving first of all the very difficult question of the literary genres of the sūrahs of the Qurʾān. We admire him for this when we think that the study of literary genres in the Bible is still in its infancy! He succeeds in distinguishing three series of texts by precise philological rules: a Prayer of Praise, Sūrah 1; a dogmatic book of which only fragments remain in the Uthmān Qurʾān, recognisable by their introductory and concluding formulas, which he calls the Corab; finally a history book, a true chronicle that unfolds in the concreteness of daily life, which he calls the Book of the Acts of Islam.”●

Father Georges de Nantes’ first review immediately launched the desired debate. Mail poured in, bringing a hundred relevant objections.● What should be his reply? “Hanna Zakarias re-examines the texts,” affirmed Father de Nantes, “not in their abusive translations but in their original version, and compares them to those of the Book of Exodus.”● This, unfortunately, had not been the case. How then should he reply to Father Youakim Mubarac, the young Lebanese priest and professor of Arabic at the Institut Catholique de Paris, who stated that “only one Qurʾānic text seems to be directly related to the text of the Bible,” but for the rest, “the Qurʾānic data undoubtedly similar to biblical data are irreducible to them, both terminologically and in their profound contents.”●

To the urgent questions of his young friend, the old Father Théry merely answered with his smiling kindness that he, Father de Nantes, would advance, with his disciples, along the path that Zakarias had only opened. It would be necessary to go further, much further, as the Dominican had said, moreover, in his Volume II: “A new plan has to be drawn up here for innovative linguistic studies.” There would be enough work to occupy “a whole team of Hebraists, Arabists, and historians of religions.”●

Thus, in his following article, the title of which is most explicit and sounds like a programme: “The Qurʾān is not Arabian,” Georges de Nantes is much less affirmative than prospective, with a very clear view of what remains to be accomplished. This was already apparent in his answer to Father Moubarac, his former seminary classmate, when he advocated applying “the method of our common master, Father Robert, which consists in explaining ‘the Bible by the Bible.’”● Let us transpose this great principle of the French school of exegesis, of which Father Robert and Father Feuillet are the masters, making it our rule to explain “the Qurʾān by the Qurʾān.”

“The only reliable document is the Qurʾān […]. The Qurʾān must be studied and then it must be explained why and how legends were born of it.”● We must avoid doing the opposite, like the Qurʾānic scholars of the West who tag along after the scholars of the East, the very inventors of the aforementioned legends, in flagrant contravention of the most elementary requirements of positive and critical scientific methodology: “They obviously recognise in the text its original meaning, at least for the most part, but very quickly they resolutely disregard it in order to go searching for some snippets of ancient truth in the depths of the legends. Despairing of ever being able to read this ancient text by themselves, they believe it is essential to confide in the Muslim exegesis.”●

We saw this in the case of Lammens, but Father Théry, himself is just as inconsequent with his story of Muḥammad’s conversion through the combined efforts of the Jewish Rabbi from Mecca and of dear and troublesome Ḵẖadīḏja!

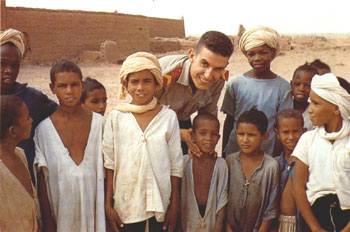

Father de Nantes, however, refusing to leave it at that, was determined to draw all the consequences from the initial intuition: “Mr. Hanna Zakarias audaciously chose a better method, that of turning his back on the traditional meaning in order to rediscover the full original meaning.” Since that work remained to be done, he entrusted it to me. During my philosophy (1956-1959) and theology (1962-1965) years at the Institut Catholique de Paris, I had as professors: the Sulpician, Father Cazelles, for biblical Hebrew, Father Hruby, for rabbinical Hebrew, and Father Moubarac, for what is known as “classical” Arabic. In addition, a twenty-seven month stay in French North Africa (Oct. 59-Dec. 61), first in the Lido military training camp, near Algiers, then in the heart of the Sahara, in the Meharist company of the Tinghert, at In Salah, introduced me to Islam in a real-life context, and convinced me of the ambiguity of a language that is only spoken, and which is so dissimilar from one region to another, even from one oasis to the next.

Father de Nantes, however, refusing to leave it at that, was determined to draw all the consequences from the initial intuition: “Mr. Hanna Zakarias audaciously chose a better method, that of turning his back on the traditional meaning in order to rediscover the full original meaning.” Since that work remained to be done, he entrusted it to me. During my philosophy (1956-1959) and theology (1962-1965) years at the Institut Catholique de Paris, I had as professors: the Sulpician, Father Cazelles, for biblical Hebrew, Father Hruby, for rabbinical Hebrew, and Father Moubarac, for what is known as “classical” Arabic. In addition, a twenty-seven month stay in French North Africa (Oct. 59-Dec. 61), first in the Lido military training camp, near Algiers, then in the heart of the Sahara, in the Meharist company of the Tinghert, at In Salah, introduced me to Islam in a real-life context, and convinced me of the ambiguity of a language that is only spoken, and which is so dissimilar from one region to another, even from one oasis to the next.

I then undertook historical research on pre-Islamic Arabia and on “The Arab Conquest,” the results of which were the subject of scientific dissertations that Father Daniélou encouraged me to publish. These works, however, were only a preparation for the realisation of a literal and systematic translation of the Qurʾān itself, which had to be completed before interpreting the results of these various studies, in order finally to reach, if possible, a proposal for a general theory on the historical origins of Islam.

I must confess, however, that this translation, immediately turned out to be fraught with so many difficulties that I would have given up a hundred times had it not been for the advice and constant encouragement of Father de Nantes who elucidated the most difficult questions with the impassive serenity that the flashes of inspiration of a superior genius gave him in every domain. May he receive here the tribute of my filial recognition.

Allow me to thank in particular, one of my professors from among all the others, Father Kurt Hruby who, from the distant times of the preparatory work, has never ceased to assist me throughout my research with his immense erudition. Without it, I would never have been able to bring this task to completion.

Finally how can I fail to express my gratitude to our brothers and sisters: typists, proof-readers, printers, binders and secretaries? Their boundless devotion has made possible the realisation of a work that concerns our common missionary vocation, with an incessant collaboration that the authors and publishers of scholarly books consider as the ideal condition for carrying out such a task.

Denise Masson (1901-1994), nicknamed the Lady of Marrakech, was a French Islamic scholar residing in Marrakech, Morocco. Her translation of the Qurʾān was published in the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 1967. It includes an introduction on the prophet Muḥammad and on the text Qurʾānic itself. Unfortunately her translation is entirely based on the Sīrah. Throughout his analysis, Brother Bruno refers to Denise Masson’s translation of the Qurʾān, along with Régis Blachère’s, for they are the only recent translators who show some concern for critical methods. Masson and Blachère will only serve Brother Bruno occasionally to emphasise the inconsistencies and contradictions of the “accepted meaning.” He does not systematically compare his exegesis with theirs. You will come to understand how totally pointless this would be as you advance in Brother Bruno’s commentary.

Denise Masson, Le Coran, Pléiade, 1967, republished in 1976, 1980, 1986, p. XL.

Denise Masson, Le Coran, Pléiade, 1967, republished in 1976, 1980, 1986, p. XVII.

Jean Grosjean (1912-2006), was a French poet, writer and translator. In 1933 he entered the Saint-Sulpice Seminary. After his military service in Lebanon (1936-37), he was ordained a priest. Mobilised, then made prisoner during World War II, his first poetry book was published the year after the war. In 1950, he abandoned the priesthood and married. His translation of the Qurʾān was published in 1979. Brother Bruno considers it a notable regression because he totally disregards the historical and critical method. Brother Bruno is therefore astonished by the approval that Grojean’s translation received from the Islamic Research Institute of Al-Azhar.

Denise Masson, Le Coran, Pléiade, 1967, republished in 1976, 1980, 1986, p. IX.

Louis Massignon (1883-1962) was a French orientalist and Islamic scholar. He was a professor at the Collège de France (a higher education and research establishment), and at the École des hautes études. His father was a rationalist, his mother a practicing Catholic. He progressively became an atheist. He was led to studying Morocco and wrote to Father Charles de Foucauld on this subject. He corresponded with him until Father de Foucauld’s martyrdom in 1916. Massignon later distorted the figure of this saint by detaching him from his nationalist context and depicting him as a pure mystic. He is known for his studies of Islamic mysticism and is considered a promoter of interfaith dialogue between Islam and the Catholic Church.

Denise Masson, Le Coran, Pléiade, 1967, republished in 1976, 1980, 1986, p. XVII.

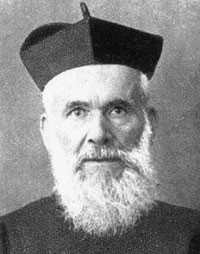

Father Henri Lammens (1862–1937) was a prominent Flemish Belgian-born Jesuit and Orientalist of Saint Joseph’s University in Beirut, Lebanon. He was the first to venture applying the rules of the modern historical and critical method to the Qurʾān. Father Lammens based his work on the Professor Ignác Goldziher concerning the historical value of the Tradition. He adopted Goldziher’s viewpoint and pursued the inquiry. Lammens’ conclusions are firm and represent a considerable advance over Goldziher’s. The latter had shown the profoundly “tendentious character” of the Tradition. Father Lammens showed its “apocryphal” nature. He positively demonstrated that the ḥadīṯ are nothing but pure inventions, that the so-called ‘eyewitnesses,’ the authorities of the Ḥadīṯ, are fictitious. Thus, the Sīrah has no historical basis other than the Qurʾān, of which it is nothing more than an imaginary elaboration: “Since the Tradition arises from the affirmations recorded in the Qurʾān,” Father Lammens stated, “it does not provide a verification or complementary information, but an apocryphal elaboration.” He was therefore able to conclude that “the Sīrah remains to be written, just as the historical Muḥammad remains to be discovered.” To do this he advocated rejecting the ‘Tradition’ in its totality, replacing its fanciful exegesis by a scientific exegesis. Although he recommended this, he never carried out this work. When Father Lammens passed away, the Jesuits of Beirut put his works under seal, and since then it has been a law of Islamology to ignore his discoveries.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, pp. 27-51.

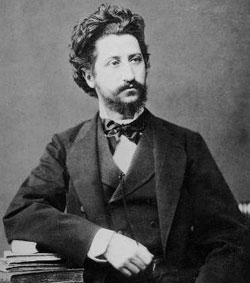

Ignác Goldziher (1850-1921) was a Jewish Hungarian scholar of Islam. He is considered one of the founders of modern Islamic studies in Europe. Goldziher’s major work is his careful investigation of pre-Islamic and Islamic law, Muhammedanische Studien published in 1890. In it, he showed how the ḥadīṯ reflect the legal and doctrinal controversies of the two centuries after the presumed death of the hypothetical Muḥammad. The Jesuit scholar, Father Lammens, based his own works on these “insightful studies of Professor Goldziher” who had thus brought to light “the profoundly tendentious nature of the [Muslim] Tradition.”

Muhammadanische Studien, Halle, two volumes, 1889-1890.

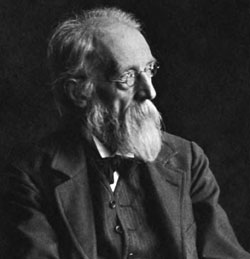

Theodor Nöldeke (1836-1930) was a German orientalist. He studied in Göttingen, Vienna, Leiden and Berlin. Along with Ignaz Goldziher, he is considered the founder of modern Islamic studies in Europe. In 1859 his history of the Qurʾān won the prize of the French Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, and in the following year he rewrote it in German (Geschichte des Qorâns). Nöldeke admitted: “In the end, I renounce exploring the mystery of the historical personality of Muḥammad.” Nöldeke is best known for his reordering of the 114 sūrahs of the Qurʾān to match what he considered to be their true historical occurrence. Nöldeke based this work on the sequence of revelation with the development of content and the origination of new linguistic styles. The Nöldeke Chronology divides the sūrahs of the Qurʾān are into four groupings: the First Meccan Period, the Second Meccan Period, the Third Meccan Period, the Medinese Period. Nöldeke considered this arrangement to be more coherent and comprehensive. Despite this attempt made by Noldëke, and later on by Schwally, Blachère, etc., Brother Bruno believes that there is no reason to give the sūrahs an order different from the one found in the accepted “vulgate.”

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, p. 27.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, pp. 30-31.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, p. 33.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, p. 48.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, pp. 33-34.

Quraishite: adjective referring to a member of the Quraish people, an Arab people. According to Muslim tradition, the hypothetical Muḥammad was a member of this people which, from the 5th century, was distinguished by a religious preeminence associated with its hereditary provision of the pre-Islamic custodians of the Ka’aba at Mecca.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, pp. 33-34.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, p. 28.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, p. 28.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, p. 40.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, p. 36.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, p. 42.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, p. 46.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, p. 44, no.°4.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, p. 42

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, p. 29.

Translation of: “présenter l’islam comme une religion née au grand soleil de l’histoire”

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, p. 50

Translation of: “l’islam naît en pleine histoire ; ses racines sont à fleur de sol. La vie de son fondateur nous est aussi bien connue que celle des réformateurs du XVIe siècle. Nous pouvons suivre année par année les fluctuations de sa pensée, ses contradictions, ses faiblesses.”

Études d’histoire religieuse, p. 220, quoted by Lammens, Études sur le siècle des Omayyades, Beirut, 1930, p. 11.

Études d’histoire religieuse, p. 220, quoted by Lammens, Études sur le siècle des Omayyades, Beirut, 1930, p. 11.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, p. 48

Chanoine René Aigrain (1886-1957) entered the Major Seminary of Poitiers in 1904 and was ordained priest in 1909. He became professor of the History of the Middle Ages at Université catholique d’Angers in 1923, where he taught until 1951. He was appointed Honorary Canon of Poitiers in 1934. From 1922 to 1924, he contributed the article Arabia to the Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques. In it, he rightly concluded that the Sīrah can no longer be used as a basis for dealing with the history of Muḥammad. Unfortunately, when it came Islam, he abandoned this fruitful point of view, simply reverting to the use of what is considered to be traditional data, writing: “This does not mean that we must retain nothing from it [the Sīrah], which would make it absolutely impossible for us to know the life of the Prophet.” This implies that even outside the Sīrah there is not one single positive fact that attests to Muḥammad’s historical existence.

Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques (DHGE), tome 3 (1924), article : Arabie

Translation of: “Tel étant le matériel documentaire dont nous disposons, deux attitudes extrêmes sont en somme possibles. L’une consiste, pour le savant européen, à traduire dans sa langue, les récits de la biographie apologétique telle qu’elle s’est peu à peu constituée dans le monde musulman à travers les évolutions de la Tradition et de la piété. L’autre qui, en fait, n’a jamais été adoptée parce qu’elle aboutirait à une renonciation, consisterait à n’admettre que ce dont la vérité peut être contrôlée, c’est-à-dire presque rien.”

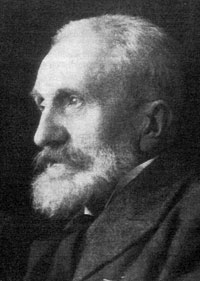

Maurice Gaudefroy-Demombynes (1862–1957) was a French Arabist, a specialist in Islam and the history of religions. He was a professor at the École nationale des langues orientales vivantes (today INALCO). His best known works are his historical and religious studies on the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca and Muslim institutions. He also translated into French in an annotated edition the story of the Arab travel writer and explorer Ibn Jubair (1145–1217). His book written after Arab authors on Syria at the time of the Mamluk is also a seminal work. Gaudefroy-Demombynes clearly realised that two extreme attitudes were possible for European scholars: either to accept the Sīrah, the only documentary material available to them, as it had been put together in the Muslim world through the evolutions of the Tradition and piety or to accept “only those things, the veracity of which could be established, that is to say, almost nothing.” Unfortunately, Gaudefroy-Demombynes adopted the first solution, even if it meant “appearing naïve in the eyes of certain people.” In order to justify his choice, he had to play down the significance of Father Lammens’ criticism of the Sīrah.

Mahomet, coll. Évolution de l’Humanité, Paris 1957, p.6.

Father Henri Lammens, S.J., Qoran et Tradition. Comment fut composée la vie de Mahomet, Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1910, Vol. I, p. 47 ; 50.

Régis Blachère (1900-1973) was a French orientalist, Arabist and Islamic scholar. He held the Arab Philosophy Chair at the Sorbonne and was the director of the Institute of Islamic Studies (Institut des études islamiques) in Paris. He published a history of Arabic literature (1952), a study on the problem posed by Muḥammad (1952), a translation of the Qurʾān (1950 and a new version in 1957), and an introduction to the Qurʾān (1959). He also co-authored a grammar of classical Arabic with Gaudefroy-Demombynes. Throughout his analysis, Brother Bruno refers to Régis Blachère’s translation of the Qurʾān, along with Denise Masson’s, for they are the only recent translators who show some concern for critical methods. Blachère and Masson will only serve Brother Bruno occasionally to emphasise the inconsistencies and contradictions of the “accepted meaning.” He does not systematically compare his exegesis with theirs. You will come to understand how totally pointless this would be as you advance in Brother Bruno’s commentary.

Régis Blachère, Le Coran, Paris-Maisonneuve, Published in 3 volumes between 1947 and 1950; it was republished as two volumes, 1977-1980. Except when he indicates otherwise, Brother Bruno quotes the original edition.

R. Chidiac, S.J., in the preface to the second edition of Lammens posthumous work, L’Islam, Beirut, 1944, p. XVI.

Mahomet fut-il sincère ? Recherches de Science Religieuse, 1911, Vol. II; L’âge de Mahomet et la chronologie de la Sirā, Journal asiatique, 10th series, 1911, Vol. XVII; Fatima et les filles de Mahomet, Rome, 1912.

R. Chidiac, S.J., quoted above, refers to what we call “inconsistency,” as an “evolution” developing from “excessive […], extreme […] starting points,” that a deeper understanding of the fiqh and the ḥadīṯ led Lammens to modify “in a sense of a broader understanding for Islam” (L’Islam, Beirut, 1944, p. XV) Whatever Lammens’ motives may have been, does this weakening of his initial requirements for scientific rigour permit Blachère to take the liberty of systematically omitting precisely this article, Qoran et Tradition, from his exhaustive bibliographies in which Lammens always appears often. He might as well not mention him at all! This is in fact what Denise Masson ends up doing. She completely overlooks our Jesuit. (Denise Masson, Le Coran, Pléiade, 1967, apercu bibliographique, p. 1013).

Father Gabriel Théry (1891-1959), Dominican, must be considered the founder of “the scientific exegesis” of the Qurʾān. Historian, theologian et author, Doctor of theology, professor at Saulchoir and at the Institut catholique de Paris, he was consultor for the Vatican Historic Section of the Congregation of Rites. He was a reputed medievalist in the scientific research community. In 1926, he co-founded with Étienne Gilson the Archives d’Histoire Doctrinale et Littéraire du Moyen Âge (ahdlma). In 1955, he self-published under the pseudonym Hanna Zakarias the first two volumes of his work, De Moïse à Muḥammad. A third volume was published posthumously in 1963. His forth volume remains unpublished. It was Father Théry's brilliant contribution to have understood that it was necessary to begin the study of the Qurʾān by comparing it to the Bible. He succeeded in solving the very difficult question of the literary genres of the sūrahs. He distinguished three series of texts: a Prayer of Praise, Sūrah I; a dogmatic book of which only fragments remain, which he called the Corab; finally a history book, a true chronicle, which he called the Book of the Acts of Islam. His monumental work became known to a great extent through the reviews that Father de Nantes wrote on it to stimulate a debate. He wrote: “Hanna Zakarias had the freedom of mind to read the Qurʾān as a document of the past and to seek to explain it by the simplest laws of the historical method.” The inspired intuition that occurred to Father Théry was that the author of the Qurʾān used the Hebrew language to give a religious vocabulary to the Arabs.

De Moïse à Muḥammad, 2 volumes, self-published in 1955 under the pseudonym Hanna Zakarias; followed by Vol. III, published posthumously by Scorpion in 1963. Vol. IV remained in draft form. We possess a typewritten copy of it. It was Angelicum, the Roman review of the Dominicans, that officially lifted the anonymity a year after Father Théry’s death, by summarising very succinctly, but accurately, the contents of the first two volumes (fascicles 3-4, year 1960)

Georges de Nantes, L’Islam, religion marginale, L’Ordre Français, no. 55, August-September 1961, p. 61.

Cf. the important admissions of Father Jomier in Études, January 1961, Les idées de Hanna Zakarias. (Father Jacques Jomier (1914-2008) was a French Dominican and Islamologue. He graduated from the Dominican Faculty of Saulchoir with a degree in Theology and a doctorate in Litterature. En 1932, he entered the Dominican Order, and was ordained priest in 1939. Later on he was sent to the Dominican priory in Cairo. It had been founded in 1928 to be an extension in Egypt of the École Biblique de Jérusalem, devoted to the study of archaeology in Egypt in connection with Biblical studies. Unfortunately, international events blocked the project. In 1953, Father Jomier became one of the three founders of the Dominican Institute of Oriental Studies (IDEO) dedicated to Islamic studies aimed at “making Islam better known and appreciated in its religious and spiritual dimensions.”)

L’Islam sous la toise, L’Ordre Français no. 8, January 1957, pp. 53-76; Father Georges de Nantes, Le Coran n’est pas arabe, no. 12, June 1957, pp. 50-68; Les chrétiens et le Coran, no. 23, June-July 1958, pp. 36-51; followed or accompanied by various replies to correspondents; especially the debate with Father Jomier, a Dominican from Cairo, L’Islam, religion marginale, no. 55, August-September 1961 et no. 57, November 1961.

Father Georges de Nantes, L’Islam sous la toise, L’Ordre Français no. 8, January 1957, p. 55.

Letter of January 6, 1957.

Father Georges de Nantes, L’Islam sous la toise, L’Ordre Français no. 8, January 1957, p. 56.

Father Georges de Nantes, Le Coran n’est pas arabe, L’Ordre Français no. 12, June 1957, p. 50.

Father Georges de Nantes, L’Islam sous la toise, L’Ordre Français no. 8, January 1957, p. 55.

Father Georges de Nantes, Le Coran n’est pas arabe, L’Ordre Français no. 12, June 1957, p. 53.

Father Georges de Nantes, Le Coran n’est pas arabe, L’Ordre Français no. 12, June 1957, p. 63.

Father Georges de Nantes, L’Islam sous la toise, L’Ordre Français no. 8, January 1957, p. 66.

Father Georges de Nantes, Le Coran n’est pas arabe, L’Ordre Français no. 12, June 1957, p. 63.

Pierre de Ronsard (1524-1585) is a major figure in the poetic literature of the Renaissance. Over a period of more than thirty years, he authored a vast body of work, focusing as much on official poetry as on lyrical poetry. Imitating ancient authors, Ronsard first used the forms of the ode and the hymn, considered major forms, but he increasingly used the sonnet. Ronsard contributed to the broad expansion of the field of poetry, giving it a richer language through the creation of neologisms and the introduction of popular language into literary French, and establishing rules of versification that have endured for several centuries.

Translation of: “pallier leur ignorance par des débauches d’imagination. Ne connaissant pas le sens direct de leurs vénérables textes et dans l’impossibilité où ils étaient de contrôler et de dépister l’imposture [...], tandis que se perdait le sens originel, de grands efforts d’imagination lui substituaient un autre sens traditionnel, mais intégralement légendaire.”

Father Georges de Nantes, Le Coran n’est pas arabe, L’Ordre Français no. 12, June 1957, p. 66.

Father Georges de Nantes, Le Coran n’est pas arabe, L’Ordre Français no. 12, June 1957, p. 52-53.

Hanna Zakarias, De Moïse à Muḥammad, Vol. I, self-published in 1955, p. 251.

Translation of: “carnet de route, psychologique, religieux et guerrier d’un rabbin juif aux prises avec les idolâtres arabes”

Hanna Zakarias, De Moïse à Muḥammad, Vol. I, self-published in 1955, p. 49.

Hanna Zakarias, De Moïse à Muḥammad, Vol. I, self-published in 1955, p. 88.

Hanna Zakarias, De Moïse à Muḥammad, Vol. II, self-published in 1955, p. 44.

Father Georges de Nantes, L’Islam sous la toise, L’Ordre Français no. 8, January 1957, p. 56.

Those who claim descent from the caliph Ali and Fatima, respectively the purported son-in-law and daughter of the hypothetical Muḥammad.

Father Lammens’ studies led him to conclude that the “Prophet Muḥammad,” is a character, a creation ex nihilo of Arabic literature that appeared 140 years after the presumed death of the hypothetical character. The same must be concluded therefore for the Caliph Uthmān who is purported to have compiled the texts of the Qurʾān as we know it today.

Father Georges de Nantes, Le Coran n’est pas arabe, L’Ordre Français no. 12, June 1957, p. 62-63.

Régis Blachère, Le Coran, Introduction, Paris-Maisonneuve, 1947, p. 4.

Régis Blachère, Le Coran, Introduction, Paris-Maisonneuve, 1947, p. 92.

G. de Nantes, Father Georges de Nantes, Le Coran n’est pas arabe, L’Ordre Français no. 12, June 1957, p. 53.

Father Georges de Nantes, Le Coran n’est pas arabe, L’Ordre Français no. 12, June 1957, p. 65.

The Uthmān Qurʾān is the name given to the final compilation of the texts that form the Qurʾān as we know it today, which is the object of Brother Bruno’s translation and systematic analysis.

Father Georges de Nantes, L’Islam sous la toise, L’Ordre Français no. 8, January 1957, p. 58.

Le débat sur le Coran, L’Ordre Français no. 10, April 1957, pp. 75-76.

Father Georges de Nantes, L’Islam sous la toise, L’Ordre Français no. 8, January 1957, p. 59.

Youakim Moubarac, (1924-1995) was a Lebanese Maronite priest, thinker and renowned theologian. After studies at the Inter-rite seminary of Ghazir, and at Saint Joseph’s Seminary in Beirut, the young Youakim was sent to France by his superiors in 1945. At the end of his studies at the Saint-Sulpice Seminary of Paris, he was ordained priest of the Maronite rite in 1947. The Maronite Patriarchate authorised him to continue his studies at the Institut catholique de Paris. In 1959, he began his academic career by teaching classical Arabic at the Institut catholique. This is where Brother Bruno attended his courses.

À propos du Coran, L’Ordre Français no. 9, February 1957.

Hanna Zakarias, De Moïse à Muḥammad, Vol. II, self-published in 1955, p. 134-135.

À propos du Coran, L’Ordre Français no. 9, February 1957, p. 77

Father Georges de Nantes, Le Coran n’est pas arabe, L’Ordre Français no. 12, June 1957, p. 56.

Father Georges de Nantes, Le Coran n’est pas arabe, L’Ordre Français no. 12, June 1957, p. 65.

Father Henri Cazelles (1912-2008), Doctor of Law and of Theology, was ordained priest in 1940 and entered the Society of Saint Sulpice in 1944. He began his teaching career at the Sulpician seminary of Issy-les-Moulineaux. There his most famous student, Father Georges de Nantes, said of him: “He was, and still is today, a well of erudition, an ocean.” Besides Greek and Hebrew, Father Cazelles knew the ancient Egyptian, Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian and Hittite languages, as well as classical Arabic. In 1954, he was offered the Chair of the Old Testament at the Faculty of Theology of the Institut catholique de Paris. This is where Brother Bruno attended his Biblical Hebrew courses (1956-1965).

Father Kurt Hruby (1921-1992) was born in Krems, Austria. His mother, of Jewish origin, converted to Catholicism in order to marry. Kurt was therefore baptised. At the time of the Anschluss in 1938, he escaped the Nazi persecution by leaving with his mother for Palestine. There he was a pioneer of Elijahv’s Qibbûs in the Jordan Valley, where he followed the rabbinical academic cursus or yeshiva. At the age of twenty, however, he decided to enter the seminary. In 1948, he returned to Europe, to Louvain, where he did his theology studies. He was ordained priest on March 18, 1956. Incardinated in the diocese of Liege, he taught at the Institut Catholique de Paris, which he joined in 1961. It was there that Brother Bruno met him. When he entered the Carmelite Seminary in 1956, Brother Bruno had already received from his master Father de Nantes the obedience of undertaking the scientific translation of the Qurʾān. He therefore assiduously attended Father Hruby’s course on rabbinical language and tradition, searching for the sources of the language of the Qurʾān. This is how he began to collect literary and philological contacts capable of explaining not only the ideas present in the Qurʾān, but also the origin of the Qurʾānic language, still absolutely unknown.

From 1964, the development of the Catholic Counter-Reformation movement founded by our Father, Fr. de Nantes, took priority and absorbed all our energy. However, Brother Bruno continued nevertheless to examine the text of the Qurʾān, collecting significant similarities of vocabulary between it and the rabbinical tradition. It was not until 1980 that Father de Nantes decided to proceed with the publication of the translation and systematic commentary of the Qurʾān. It is then that Brother Bruno resumed contact with Father. Hruby. He received him, was lavish with his encouragement, devoting whole days to answering Brother’s questions and providing him with every desirable learned reference. Brother Bruno submitted to him the proofs of the first volume of our translation of the Qurʾān before having it printed. Father Hruby wrote to him: “You know that in the interest of the cause, I would not hide from you any possible reservations, but there are none to make. Quite the contrary: what I have read so far seems to me to be solid, balanced, well presented and sufficiently irenical for no accusations based on assumptions to be made against you. You know, alas, the mentality of most people: they are less interested in the value of things than in where they come from… Still, one must not be too concerned about that; everyone is entitled to wear his “badge” proudly! Of course, I am not an Arabic scholar and therefore have no competence in that field. But it is also true that generations of professional Arabic scholars have failed to advance by so much as an inch in the fundamental question, which is that of the origins of the Qurʾān. And it is high time for this wall of silence to be breached. Not living in the “Land of Islam” and having no interest in gaining a “satisfecit” from the El-Azhar, you are sufficiently independent to be able to say things without pulling punches.” In 1992, Father Hruby wrote to Brother Bruno, “To hear that you are back working on the Qurʾān again is the best news of all. In this field you are doing a work that will last, the importance of which will, I am sure, be fully appreciated one day. The world of Islam is in a state of ferment, and the true nature of its foundation document, constantly referred to here, there and everywhere, is still cloaked in the darkest obscurity.”

Cardinal Jean Daniélou (1905-1974) was a French Jesuit priest, renowned theologian. He was created cardinal by Paul VI in 1970. Son of an anticlerical politician and a foundress of Catholic educational institutions for girls, Jean Daniélou studied literature and philosophy at the Sorbonne. In 1929, he entered the Jesuits and devoted his life to teaching. After studying theology at the Catholic Faculty of Lyon, he was ordained priest in 1938. He founded the collection “Sources chrétiennes” in collaboration with Henri de Lubac. After reading Brother Bruno’s scientific dissertations on the results of his historical research on pre-Islamic Arabia and on the Arab Conquest, he encouraged him to publish them.