THE NAMĀRA INSCRIPTION

(328 a.d.)

The Namāra inscription was chiselled into a basalt lintel (length: 1.73 m; height: 0.45 m). It had fallen from the door of a ruined tomb, near Namāra, on the site of an ancient Roman post, east of Jebel Druze. This monument is currently kept in the Louvre Museum.

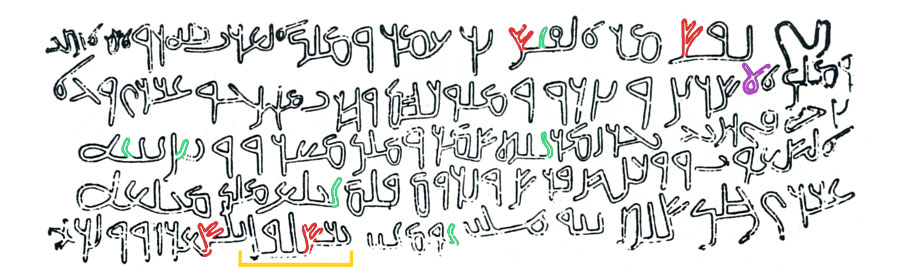

Here is a facsimile of the stamp executed in 1901 by Dussaud and Macler:●

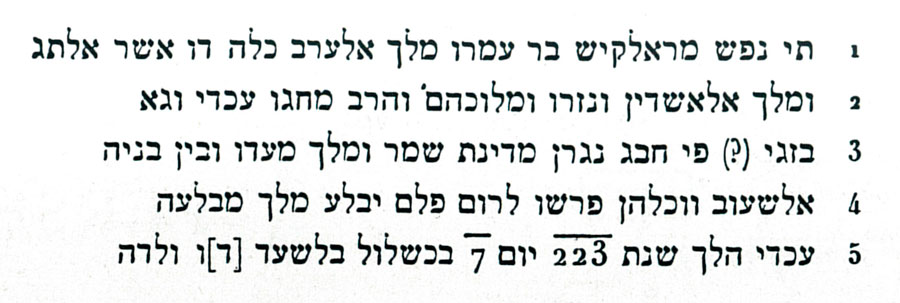

The text is difficult to decipher and interpret because it was not accompanied by a Greek translation. All the authors seem to have rallied to the views of Clermont-Ganneau who, “in spite of the Nabataean script and some purely Aramaic terms [...] soon recognised the so-called classical Arabic.”● The transcription “in Arabic” proposed by Dussaud● is, however, an inadmissible anachronism, since, as everyone agrees, Arabic writing did not yet exist. On the other hand, the transcription in Hebrew characters (below, based on Dussaud●), which are the true ancestors of the Namāra inscription’s script, makes it possible to measure the evolution that would lead, two hundred years later, to Arabic proper in the Zabad inscription. (Both the text of the Namāra inscription and its Hebrew transcription are to be read from right to left.)

- This is the tomb of Imru l-qays, son of ʿAmrū, king of all Arabs the one who wore the crown

- and reigned over the two Asad and Nizār and their kings; he prevailed over Magog (?) to this day and was victorious

- at the siege of Najrān, the city of šammar; he ruled over Maʿadd and divided among his sons

- the tribes and organised them into corps of troops for Rome. No king has attained his glory

- to this day. He died in the year 223, the seventh day of kislūl. May happiness be upon his posterity!

Compared to the Umm-al-Jimāl inscription, the Namāra inscription shows a significant evolution of the Nabataean characters towards an Arabic script. The ligatures are more numerous than in Umm-al-Jimāl: the shin is linked on the right to the letter that precedes it, and the yod on the left to the letter that follows it. Furthermore, the letters are rounder in shape. The samech has disappeared, as seen in the word kšlūl (line 5), Aramaic name for the month of kisleu, corresponding to December. Already we distinguish the lām alif (line 2), on the word ʾlʾšdīn: it is a lamed placed on a Nabataean aleph.

It is impossible here to justify in detail our translation which is, moreover, conjectural like all those that have been adopted to date. Let us just emphasise two points. The first concerns “the crown,” ʾltj (line 1) that authors claim to be a “Persian word,”● while the word tāgāʾ is Aramaic.● This “crown” was therefore not necessarily “conferred by the Persians,”● and is not absolutely incompatible with the allegiance to Rome that line 4 of the inscription seems to attest.

The second point concerns the date of Imru l-qays’ death. It is set exactly on December 7, 223 of the Boṣra era, that is, 328 a.d. As Dussaud admits: “Arab sources provide no serious information about this era.”● They cannot therefore prevail over the positive data revealed by this monument, which affirm what Dussaud calls “the extreme mobility of the large-tented nomads in organising a ghazou (armed band). The fact of reaching Nedjrān was remarkable, so it is mentioned as one of the brilliant actions of Imru l-qays, but it is not something impossible; the example of Aelius Gallus proves it.● The whole question is whether Imru l-qays performed this feat on behalf of the Romans or on behalf of the Persians. Clermont-Ganneau detected a reference to the Persians in the third word of line 4: pršū, which leads to translating: “he organised them for the Persians and the Romans.” Dussaud came round to this point of view after having first conjectured “an Aramaic term related to the root prš, ‘separate, divide,’ and having the technical meaning of ‘unit of troops.’ ”● In our Volume I,● we followed the views of Clermont-Ganneau by making Imru l-qays a “king of Ḥira.” Today, however, these views seem to us too dependent on “Arab sources.” This king could not have worked for both the two rival empires at the same time. Moreover, the presence of his funerary stele in Syria, a Roman province, proves that he finally opted for the Romans who never lost sight of the affairs of Arabia.

René Dussaud, with the collaboration of Frédéric Macler, Mission dans les régions désertiques de la Syrie moyenne, in Nouvelles archives des missions scientifiques, Vol. X, Paris, 1903, p. 314.

René Dussaud, with the collaboration of Frédéric Macler, Mission dans les régions désertiques de la Syrie moyenne, in Nouvelles archives des missions scientifiques, Vol. X, Paris, 1903, p. 314; cf. James Février, Histoire de l’Écriture, Payot, 1948, 2d ed., 1959, p. 263

René Dussaud, with the collaboration of Frédéric Macler, Mission dans les régions désertiques de la Syrie moyenne, in Nouvelles archives des missions scientifiques, Vol. X, Paris, 1903, p. 315

René Dussaud, with the collaboration of Frédéric Macler, Mission dans les régions désertiques de la Syrie moyenne, in Nouvelles archives des missions scientifiques, Vol. X, Paris, 1903, p. 315

René Dussaud, with the collaboration of Frédéric Macler, Mission dans les régions désertiques de la Syrie moyenne, in Nouvelles archives des missions scientifiques, Vol. X, Paris, 1903, p. 317

Tg Ct 3:1; Tg II Est 2:17, and passim

René Aigrain, Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques (DHGE), tome 3 (1924), col. 1221, art. Arabie

René Dussaud, with the collaboration of Frédéric Macler, Mission dans les régions désertiques de la Syrie moyenne, in Nouvelles archives des missions scientifiques, Vol. X, Paris, 1903, p. 321

René Dussaud, with the collaboration of Frédéric Macler, Mission dans les régions désertiques de la Syrie moyenne, in Nouvelles archives des missions scientifiques, Vol. X, Paris, 1903, p. 319

René Dussaud, with the collaboration of Frédéric Macler, Mission dans les régions désertiques de la Syrie moyenne, in Nouvelles archives des missions scientifiques, Vol. X, Paris, 1903, p. 320

Brother Bruno Bonnet-Eymard, The Qurʾān, Translation and Systematic Commentary, ed. CRC, 1988, Vol. I, p. 296