THE INSCRIPTION OF SAINT SERGIUS’ BASILICA

IN ZABAD

(512 a.d.)

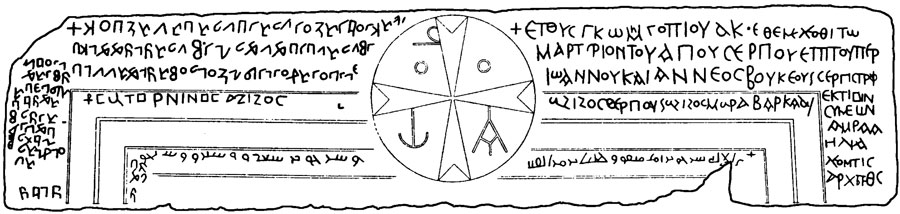

A dark grey basalt lintel (length: 3.05 m; height: 0.67 m) from the gate of a basilica dedicated to Saint Sergius. It was found by Sachau in 1879, in the midst of the Roman ruins in Zabad, in the Syrian Desert near Aleppo. It is now held by the Royal Museum of Art and History in Brussel, where it was transported in 1903 through the mediation of Father Lammens, the Jesuit scholar at the University of Saint Joseph in Beirut. Drawing of the whole work and facsimile of the Greek, Aramaic, and Arabic dedication that is found engraved on it.●

As Nau noted, “this is not strictly speaking a trilingual inscription, for to be trilingual the same text must be given in three different languages; in Zebed, however, only a part of the Greek and Syriac texts written in the year 512 a.d. correspond. It is a bilingual Greek-Syriac inscription, to which new Greek and Arabic proper names were added later on,” which constitute “rather a sgraffito than an inscription.”● Syriac is the popular language; Greek is the urban, official and literary language. Arabic, the newcomer, destined soon to supplant Greek and Syriac, appears, for the time being, as a creation of the Christian Arabs of Syria.

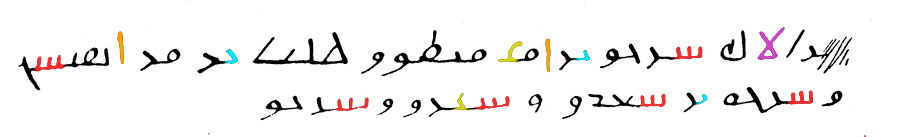

The Arabic inscription running along the bottom between two rows of oval-shaped ornaments, on the bevelled surface, on either side of the Cross of Christ, lists the names of the donors preceded by an initial formula. It is necessary to denounce Lidzbarski’s anachronism.● He interpreted the beginning of this formula: [bis]mi llāh, as though the Qurʾānic basmala were already used on the pediment of a Christian church at the beginning of the 6th century! As Kugener established: “The last letter of the first word is a rā, not a mim.”● The inscription then lists the names of five of the Arab faithful, each new name being preceded by the conjunction waw. Three of them are named “Sergius,” with the Nabataean ending in waw. It is perhaps “the oldest testimony of the veneration of the Arabs for Saint Sergius.”● Littmann points out that the first Sergius was probably the son of a slave; as for Hannaiʾ, he is identified, according to Littmann,● with Annéos of the Greek inscription. In any case, the parents of the first two Arab faithful were still pagans, if one judges from their names.

Under the sign of the monogram of Christ

To the right of the monogram of Christ, on the left for the reader, a dedication in Syriac is carved on the upper part of the lintel in a script imitating Greek writing. The text is dated to “the year 823, the 24th of Ilul” of the Macedonian calendar and of the Seleucid era used in Syria, corresponding to September 24, 512 of the Christian era.●

To the left of the monogram of Christ, on the right for the reader, a dedication was carved in Greek: “In the year 823, on the 24th of the month of Gorpiaios, was laid the first stone of the martyrium of Saint Sergius under the periodute John, also called Anneos, son of Borkaios, and three Sergius founded it. Simeon, son of Amraas, son of Elijah, and Leontios were their architects. Amen.” A “periodute” is a missionary. The numbers of the date of inscription (line 1) were written from right to left, as in Syriac and Arabic, as well as the last two letters θC, instead of Cθ (line 9), considered as numerical signs, whose sum equals 99, a number that often appears in inscriptions as a cryptogram of the word Amen.

THE BIRTH OF ARABIC WRITING

- With the help of God, Sergius, son of Amat Manaf and Hannai’, son of Imru l-qays,

- and Sergius, son of Saʿd et Sitr (?), and Sergius.

The Arabic part of the inscription, copied in 1894 by Barthélémy, published in 1897 by Maspero, reproduced by Kugener,● that is translated in the light of the Greek names added to the Greek inscription.●

Most of the letters have approximately the form that characterise, a hundred years later, Qurʾānic writing. The alif is reduced to a vertical bar (line 1); the lām-alif is purely Arabic, as well as the sin; the form of the beth and the taw is evolving in such a way that it is becoming harder to distinguish them.

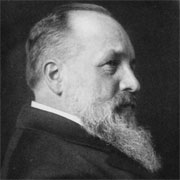

Carl Eduard Sachau (1845–1930) was a German orientalist. He studied oriental languages at the Universities of Kiel and Leipzig, obtaining his PhD at Halle in 1867. Sachau became a professor extraordinary of Semitic philology (1869) and a full professor (1872) at the University of Vienna, and in 1876, a professor at the University of Berlin, where he was appointed director of the new Seminar of Oriental languages (1887).

Carl Eduard Sachau (1845–1930) was a German orientalist. He studied oriental languages at the Universities of Kiel and Leipzig, obtaining his PhD at Halle in 1867. Sachau became a professor extraordinary of Semitic philology (1869) and a full professor (1872) at the University of Vienna, and in 1876, a professor at the University of Berlin, where he was appointed director of the new Seminar of Oriental languages (1887).

He travelled to the Near East on several occasions. He is especially noteworthy for his work on Syriac and other Aramaic dialects. He was an expert on Persian polymath Al-Biruni and wrote a translation of Kitab ta'rikh al-Hind, Al-Biruni's encyclopedic work on India. Sachau also wrote papers related to Ibadism. He was a member of the Vienna and the Prussian Academy of Sciences, and an honorary member of the Royal Asiatic Society in London and the American Oriental Society.

after Lidzbarski, Handbuch der nordsemitischen Epigraphik – Dictionary of North Semitic Epigraphy – 1898, Vol. II, pl. XLIII, 10

François Nau, Les Arabes chrétiens de Mésopotamie et de Syrie du septième au huitième siècle, Cahiers de la Société Asiatique, Vol. I, Paris, 1933, p. 97

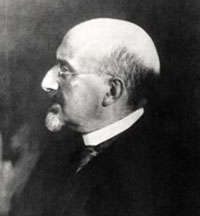

Mark Lidzbarski [né Abraham Mordecai] (1868–1928) was a German philologist and epigraphist specialising in Semitic scripts. Lidzbarski was born in Russian Poland and received a strict Hassidic Jewish education. At 14, he ran away from home and went to Posen in Prussian Poland, where he studied at a gymnasium (a European secondary school that prepares students for university). At the University of Berlin, he studied Semitic philology, living in difficult conditions. While there, he converted to Evangelical Christianity and changed his forename to Mark. In February 1896, he obtained his doctorate in Middle Eastern studies at the University of Kiel and began lecturing there in Oriental languages; then, in 1907, at the University of Greifswald; and finally, in 1917, at the University of Goettingen as successor of Enno Littmann. He was a corresponding member of the Goettingen Society of Sciences and Humanities from 1912 to 1918, when he became a full member. Lidzbarski was a scholar of high repute in several branches of Semitic studies. He may be considered the founder of Semitic epigraphy; several of his articles and books still may be consulted with great profit.

Mark Lidzbarski [né Abraham Mordecai] (1868–1928) was a German philologist and epigraphist specialising in Semitic scripts. Lidzbarski was born in Russian Poland and received a strict Hassidic Jewish education. At 14, he ran away from home and went to Posen in Prussian Poland, where he studied at a gymnasium (a European secondary school that prepares students for university). At the University of Berlin, he studied Semitic philology, living in difficult conditions. While there, he converted to Evangelical Christianity and changed his forename to Mark. In February 1896, he obtained his doctorate in Middle Eastern studies at the University of Kiel and began lecturing there in Oriental languages; then, in 1907, at the University of Greifswald; and finally, in 1917, at the University of Goettingen as successor of Enno Littmann. He was a corresponding member of the Goettingen Society of Sciences and Humanities from 1912 to 1918, when he became a full member. Lidzbarski was a scholar of high repute in several branches of Semitic studies. He may be considered the founder of Semitic epigraphy; several of his articles and books still may be consulted with great profit.

Lidzbarski, Handbuch der nordsemitischen Epigraphik – Dictionary of North Semitic Epigraphy – 1898, Vol. I, p.484

Marc-Antoine Kugener (1873-1941) was a Belgian orientalist and historian of religions first and foremost, although he ultimately became a Latinist. He studied brilliantly at the University of Liège and in 1895 was awarded the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and Letters with the highest distinction. In 1896, Kugener received a travel grant and used it for a long stay in Paris, where he attended courses in the history of religions and oriental languages at the École pratique des Hautes Études, the Collège de France and the Institut Catholique. He then spent the summer of 1897 in Bonn. He returned to Paris the following academic year. From then on he turned his attention entirely to orientalism and the study of the end of paganism in the East. In 1903, the University of Brussels distinguished the young scholar and appointed him lecturer for Greek and Latin palaeography and epigraphy, as well as for Hebrew and Syriac.

In 1905, he participated in the XIVth Congress of Orientalists in Algiers, where his authority as a scholar was definitively established due to his publications in the Patrologie Orientale. His scholarly work was interrupted by World War I. At the end of the war, he resumed his university teaching. After a term as Dean of the Faculty, Kugener was able to return to normal scientific activity. He was one of the founders of the new Latin studies journal Latomus (1937). Illness, however, was already undermining him. His was exhausted by his heavy workload. The University granted a long leave of absence, but death suddenly struck him down in 1941.

Kugener’s scientific output was not extremely abundant. Scrupulous, methodical and conscientious, sometimes to the point of excess, Kugener spent years in patient and meticulous research. It was his perpetual self-doubt, his desire to deliver only a perfect work, that prevented Kugener from completing many of his studies and they remain in a state which precludes their publication. He did, however, produce some important works that left a mark on the field of orientalism.

Nouvelle note sur l'inscription trilingue de Zébed, in Rivista degli studi orientali, vol. I, 1908, p. 583

Kugener, Nouvelle note sur l'inscription trilingue de Zébed, in Rivista degli studi orientali, vol. I, 1908, p. 585. On the devotion of the Arabs to Saint Sergius, cf. Henri Charles, s.j. Le christianisme des Arabes nomades sur le Limes et dans le désert syro-mésopotamien aux alentours de l’Hégire, Leroux, Paris, 1936, p. 29-35

Littmann, Rivista degli studi orientali, IV, 1911, p. 196

Georges de Nantes

Kugener, Nouvelle note sur l'inscription trilingue de Zébed, in Rivista degli studi orientali, vol. I, 1908, plate I, no. 3.

cf. Littmann, Rivista degli studi orientali, IV, 1911, 2, pp. 196-197