2. In the Qurʾān: Muḥammad

The author of Sūrah 3 refers to himself as muḥammadun (verse 144) which, since the most remote origins, has been regarded as a proper noun, the personal name of the founder of Islam: “Muḥammad.”

In the 9th century, two hundred years after the events recounted in Sūrahs 2 and 3, Ibn Ḥišām established the framework of the Sīrah, or Life of Muḥammad, the basic structure of which would then remain unchanged until our time.

The Sīrah is composed of ḥadīṯ, “accounts,” that “the companions of the Prophet handed down to the second generation of believers, that of the Followers, who themselves entrusted it to the Followers of the Followers.”● Through these “chains of narrators,” we arrive at the first collections of “Traditions”: the collection of Mūsā ibn ʿUqba (died circa 758), from Al Madīnah, relating to the maġāzī, “campaigns” of Muḥammad; and that of Ibn Isḥāq, another inhabitant of Al Madīnah of the same period (704-768) who “wrote or dictated a vast work in which, for the first time, the Life of the Founder of Islam is presented in chronological order.”●

Thus, “the oldest collections of historical traditions take us back to about one hundred and twenty-five years after the period of the prophet’s activity.”● Régis Blachère does not conceal that “this fact poses multiple and irritating problems” concerning the person and work of these authors, for example Ibn Isḥāq: “Only one point is certain: the writing of this ‘holograph’ was a collection of chronologically ordered accounts on the history of the ancient nations and on the Prophets until Muḥammad’s advent and his triumphant preaching.”●

In the following century, “a ‘traditionist’ from Basra, Ibn Hicham (died 834), about whom very little is known,” subjected Ibn Isḥāq’s compilation to a “severe pruning. The developments on the Prophets prior to Islam disappear.” Above all, Ibn Ḥišām encloses “the whole of the biographical literature devoted to Muḥammad in Islam” in “a vicious circle”: “The allusions contained in the Qurʾān must serve as a support for the Biographical Tradition without which, precisely, they themselves remain a dead letter.”●

It was not until the 19th century, however, that Western orientalists discovered this “vicious circle.” In sixty years, from Weil (1843) to Caetani (1905), the inevitable conclusion emerged: “We can find almost nothing true about Muḥammad in the Tradition, and we can dismiss as apocryphal all the traditional materials that we possess.”●

Today, this is the pure and simple scientific truth: “Nothing ever allows us to say: this unquestionably goes back to the time of the prophet,” Rodinson wrote.● Yet neither Blachère nor Rodinson resigned themselves to adopting the “scientific attitude” that “began” in the fields of “Roman history” and “biblical history,” Rodinson wrote, “when it was decided to accept a fact only if the source that reports it was proved to be reliable and only insofar as it was proved to be reliable.”● The reason for not adopting this scientific attitude is that one would have “to resign oneself to writing the origins of Islam only with the allusions offered by the Qurʾān.”● This is what no one, not even Father Lammens, s. j., from 1910 on, let alone Father Théry, o. p. (1957) dared to undertake [see sections I and II ] although the studies of Schrieke and Horovitz have confirmed on all counts the radical conclusions of Caetani.

Due to this lack of a scientific approach, and in defiance of all logic, the traditional legend thus regained authority among orientalists, under the impetus given by Nöldeke, Becker and Goeje. We will summarise it first by citing the most recent French-language biographies of Muḥammad. All of them proceed from an exhaustive knowledge of the immense Arabic literature that enriches the different chapters of Ibn Isḥāq, al-Buẖāri (died in 870), and Ibn Saʿd (died in 843) disciple of al-Wāqidī (died in 823).

THE LEGEND

According to this “Tradition,” Muḥammad was born in Mecca of a father called ʿAbd Allāh and of a mother named Amīna. “Abd Allāh’s beauty made him the Joseph of his time.”●

“Allāh watches over the conception of every human being, but he especially favours that of the prophets; just as the spirit rūḥ brought the breath of Allāh into the womb of Mary, mother of Jesus, an angel transmitted to ʿAbd Allāh a ray of divine light nūr.”●

After the conception of the child by Amīna his wife, ʿAbd Allāh no longer had this brightness on the forehead. And “tradition reveals that the monthly accidents had barely stopped for Amīna: she became almost immaculate.”●

As for the child, at his birth, he had on his back between the two shoulders the mark of prophecy: “A small but very distinct oval-shaped mark, where the skin was slightly swollen, similar to the imprint left by a suction cup.”●

MUḤAMMAD’S CHILDHOOD

ʿAbd Allāh died before the birth of the child. He was entrusted to his grandfather, ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib, who put him in the care of a wet nurse among the desert Bedouins of the Meccan region.

During this stay in the desert, the child experienced a purification of his heart: “Two angels came, opened his breast, took out his heart that they carefully cleansed before putting it back in its place. Then they weighed him by successively putting on the other plate a man, then ten, then a hundred, then a thousand. Then one said to the other: ‘Let’s leave it at that! Even if you were to put his entire community (omma) on the other plate, he would still weigh more than it’.”●

The child lost his mother at the age of six. ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib, his grandfather, took a liking to him. “Almost every day they were seen together, hand in hand, at the Kaʿbah or in some other corner of Mecca.” ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib went so far as to bring Muḥammad with him when he went to the Assembly where the notables of the city, all more than forty years of age, met to discuss various issues, and the octogenarian was not afraid to ask the seven-year-old for his opinion on this or that point. When the other dignitaries expressed their surprise, he always said: “A great future awaits my son.”●

The orphan lost his grandfather and was taken in by his uncle Abū Tālib. He had a happy childhood, pampered by his aunt Fāṭima. “He often tended sheep and goats, thus spending many days in the solitude of the mountains that dominated Mecca or on the slope of more distant valleys.”● “Divine favour was careful to preserve him from any fault; a voice reminds him of sexual modesty.”●

HIS YOUTH

“It also happened that his uncle took him along with him on journeys and so once, when Muḥammad was nine or, according to some, twelve years old, they went to Syria with a caravan of merchants.”● A Christian monk named Bahīrā lived in Boṣra. He was waiting for the coming of a prophet sent by God to the Arabs, announced by certain Scriptures, ancient manuscripts in his possession.

When Bahīrā saw the caravan approaching, he observed that “a small cloud was moving gently at low altitude above the heads of the travellers, so that it always acted as a screen between the sun and one or two of them.” This cloud stopped at the same time as them, “remaining motionless above the tree under which they had taken shelter and which, itself, had lowered its branches in such a way that the travellers were doubly shaded.”●

Having been shown the child, the monk recognised in him the expected prophet: “Bring your brother’s son back to his country and protect him from the Jews,” he recommended to Abū Tālib. “For, by heaven, if they see him and if they know about him what I myself know, they will seek to harm him. Great things lay in store for your brother’s son.”●

Fifteen years later, Muḥammad again made the journey on behalf of the widow Ḫadīja, whose goods he was transporting to Syria. When he arrived at Boṣra, he stopped near the cell of a Christian monk named Nestor, who in turn told Muḥammad’s companion, Maysarah, that he was “nothing less than a prophet.”●

On the way back, Maysarah noticed “for a slight moment but very clearly, two angels who protected Muḥammad from the sun’s rays.”●

Ḫadīja, informed about these wonders by Maysarah and seduced by the beauty of Muḥammad, whose transactions earned her wonderful profits, married him. He was twenty-five years old, she was forty. She bore him seven children: three sons who died in infancy, and four daughters, the youngest of whom, Fāṭima, would marry ʿAli, Muḥammad’s cousin, “and was destined for the tragic honour of perpetuating his race.”●

THE DIVINE CALL

One day, unexpectedly, a voice made itself heard. It was probably the first time that a feeling of something extraordinary was so clear, otherwise the agitation of the pious Meccan would be inexplicable. The Voice said three Arabic words that would drastically change the world: “You are the messenger of God!”●

It happened in the area around the cavern of Mount Ḥirā close to Mecca where Muḥammad went into retreat every year in the month of Ramaḍān. The event is dated around 610 a.d or a few years thereafter.”● Muḥammad was forty years old.

One day, “Muḥammad was asleep in the cavern of Ḥirā when he had a dream. He saw himself struggling with an Angel who ordered him to recite a passage that is recorded in the Qurʾān (Q 86:1-5) [...]. Since Muḥammad refused three times to obey, the Angel struck him down and crushed him to the point of suffocating him; the Angel did not relent until he had submitted. At this moment, Muḥammad woke up. Then the real miracle took place: “I came out of the cavern,” Muḥammad related, according to Ibn Isḥāq. “As soon as I arrived halfway down the mountain, I heard a voice coming from heaven, which said: ‘O Muḥammad! You are the Apostle of Allah, and I am Gabriel.’ I raised my head skyward to look. There Gabriel was, having the appearance of a man with his heels joined, in the sky at the horizon, and he said to me: ‘O Muḥammad! You are the Apostle of Allah, and I am Gabriel.’ I stopped while looking at him without being able to advance or retreat. Then I found myself turning away from him towards the other corners of the horizon, but I was unable to look at any corner of the sky without seeing the Angel in the same attitude: I remained thus, standing, without being able to advance or turn back. The Angel finally left and I returned to my family. When I arrived close to Ḫadīja, I sat on her lap and snuggled up to her, then I told her what I had seen. ‘Good news,’ she then exclaimed. ‘Persevere! By the One who holds the soul of Ḫadīja in his hands! I hope you will be the prophet of this nation’.”●

THE REVELATION OF THE QURʾĀN

First communicated to Muḥammad in a single night of Ramaḍān by the angel Gabriel, this revelation was then repeated according to the circumstances. “At no time did Muḥammad see Allah or hear his voice. Only the divine messenger spoke to him to inspire him with speeches for other men. Muḥammad’s duty was to convey this message, a sacred obligation for which he would be accountable to his Lord.”●

“The insistence with which Tradition harks back to the external phenomena affecting the Prophet that accompany the coming of a revelation reveals the deep impression left by them in the minds of those who had witnessed them. Of course, we have no information on the concomitant phenomena of the first revelations. On the other hand, traditional data enlightens us very well on those of a later era. The inspired Bedouin was sometimes overcome by incoercible shivers and asked to be wrapped in a woollen cloak: the Qurʾān, twice, bears witness to this fact. On the contrary, at times, even in the coldest weather, according to ʿĀʾiša, ‘his forehead was streaming with sweat.’ Other information insists on the spasms that shook the body of the inspired Bedouin, on the hoarse and inarticulate cries that his mouth uttered, then on the sudden appeasement that announced the end of the fit.”●

“At first, it seems that Mohammad wanted to hasten the expression of what he perceived by stammering and stuttering. It is perhaps to this disordered effort that correspond the few consonants that are at the beginning of some Sūrahs of the Qurʾān and on which many hypotheses have been made.”●

“The idea of noting revelations soon came to the minds of believers who were able to wield a reed pen. There are indications that this writing was partial and very precarious, both because of the material used at that time (shards of pottery, pieces of leather or camel shoulder blades), and because of the graphic system in use: it was indeed still so rudimentary that a text could only be properly deciphered if it was known by heart.”●

This is why “during a period, the duration of which it is impossible to assess, the revelations were therefore entrusted to the sole memory of the faithful.”●

THE APOSTOLATE

One day, Gabriel came to Muḥammad “on one of the hills overlooking Mecca and, striking the grass that covered the ground with his heel, he brought forth a spring. He then performed the ritual ablution to show the Prophet how to purify himself before prayer, and the Prophet did as he had done. Then Gabriel taught him the attitudes and movements of prayer: standing position, inclination, prostration and sitting position, with the formula of glorification to be repeated, that is, the words Allāhu akbar, God is the Greatest, and the final salute: as-salūmū ʿalaykum, Peace be upon you, and the Prophet did as he was shown. The Angel having left him, the Prophet returned home; he taught Ḫadīja everything he had learned, and they performed the prayer together. Religion was now established on the basis of ablution and prayer.”●

ʿAli, Muḥammad’s ten-year-old cousin, became a Muslim, along with Zayd, his adopted son, and two notables: ʿUṯmān and Abū Bakr. “Abū Bakr was loved and respected because of his vast knowledge, his affable manners and his pleasant company. He was often consulted on this or that matter, and he began to open up to all those he considered trustworthy, exhorting them to follow the Prophet.”●

Thus Islam began to spread in Mecca, breaking with ancestral Arab paganism. Yet “the more the number of believers increased, the more the hostility of the unbelievers became exacerbated.”● It ended in insults and then assaults: “Each of the clans took care of its own Muslims. Muslims were imprisoned, beaten, deprived of food and drink; or they were kept lying on the scorching ground of Mecca during the hours of greatest heat to force them to deny their religion.”●

The Meccans were polytheists. The Kaʿba was the shrine where they worshipped their gods and goddesses. Now, the Muslims, disciples of Muḥammad, continued to go there, but to worship Allah, in defiance of the idols. “Mecca was now a city divided between two religions and two communities.”●

A group of eighty Muslims emigrated to Abyssinia where they received the best reception from the Negus.● At Mecca, the Muslims were banished from the city. After two years of persecution, however, the measure was revoked; the emigrants were able to return. There was a time of peace.

In 619, Ḫadīja died at the age of sixty-five. “Her four daughters were grief-stricken, but their father was able to console them by telling them that Gabriel had come to him once and instructed him to convey to Ḫadīja greetings of Peace from her Lord and to tell her that he had prepared for her a dwelling in Paradise.”●

AN OVERNIGHT TRIP TO JERUSALEM

One night, the angel Gabriel awakened Muḥammad who was asleep in the Kaʿba, and led him to the door where there stood “a white animal, taking after a mule and an ass, which bore wings on its flanks that served to activate its legs; and each of its strides covered the distance that the eye is able to embrace.”●

The name of the animal was Burāq. The Prophet mounted him and “the Archangel at his side showed the way and kept the pace set by the heavenly steed; they sped northward, passed Yathrib and Khaybar and finally reached Jerusalem. There, a group of prophets – Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and others – came to meet them, and when Muḥammad began to pray at the Temple site, they lined up behind him for prayer.”

Then he got back on Burāq and the animal rose vertically, led by the Archangel Gabriel through the seven Heavens, where they met again the prophets with whom he had prayed in Jerusalem, but transfigured. Having reached the “Lotus of the Limit” which is rooted in the very Throne of Allah, Muḥammad heard “the verse that contains the creed of Islam” (Sūrah 2, verse 285).”

“When the Prophet and the Archangel came back down to the rock of Jerusalem, they returned to Mecca by the same path they had taken to come, overtaking many caravans that were heading south. It was still dark when they arrived at the Kaʿba.”●

Muḥammad was jeered at when he related how he had made in one night the return trip to Jerusalem, which takes no less than two months for a caravan. He, however, proved the veracity of his words by describing the caravans he had passed on the way back, indicating their location and the day on which they could be expected to arrive at Mecca. For each one arrived as anticipated.

MUḤAMMAD'S WIVES

Muḥammad was fifty years old when Ḫadīja died. He married a thirty-year-old widow, Sawdah who, along with her first husband, had been a member of the group of Muslims who had emigrated to Abyssinia.

An angel told Muḥammad in a dream to ask for ʿÂʾiša’s hand in marriage. She was Abū Bakr’s youngest daughter, aged six. A contract was made between Muḥammad and Abū Bakr, and the marriage was celebrated when the child was nine years old.●

In Al Madīnah, Muḥammad “gradually built up a harem [...] made up of women whom he took in for social or political reasons.”●

THE HIJRAH

The Meccans were increasingly violent in their persecutions against Muḥammad and his followers. He therefore thought of fleeing and seeking refuge in the oasis of Ṭàʾif, where he suffered the same rebuff. So he turned to Yatrib, later called Al Madīnah, where his followers began to emigrate in small groups until Muḥammad and Abū Bakr themselves joined them.

It was in 622 a.d., the year that marks the beginning of the Muslim era.●

To characterise the inspiration that Muḥammad permanently enjoyed from then on, Blachère wrote: “Like Teresa of Avila, after 1562, the founder of Islam, from the beginning of his mission, felt Allah to be a permanent guide. After the Emigration to Al Madīnah, undoubtedly under the pressure of the new atmosphere, this feeling grew stronger in him and seemed to govern all his activity. Through the archangel in whom Muḥammad recognised Gabriel, Allah no longer transmitted only his word to his Apostle; he became the steward of everything that bound the Community; he suggested projects, provided the means, revealed snares and factions, gave constancy in the trial, revealed the word or the decision that dispelled hesitations and inspired audaciousness.”●

MUḤAMMAD’S CAMPAIGNS

Muḥammad successfully launched his first raid on a Meccan caravan in Naẖla (January 624).●

Two months later took place the Battle of Badr (March 624), a resounding victory of the Muslims over their Meccan enemies, twice as numerous.

This success was followed by a crushing defeat in Uḥud (March 625), where it was believed for a moment that Muḥammad had been killed.

After an attempt to rally the Jews of Al Madīnah to his cause, Muḥammad successively expelled two clans whose property he confiscated, and he dispersed the third during the Battle of the Trench (March 627). Besieged by a Meccan army, Muḥammad had dug a trench, intended to break the charge of the enemy horsemen. After fifteen days of siege “the elements – and also the angels – joined the fray and a tornado struck throwing the camp of the attackers into disarray.”● On this occasion, Muḥammad got rid of “two elements of the opposition in Al Madīnah: the Hypocrites and the Jews. The defensive period came to an end. Islam began its conquest of the world.”●

Muḥammad exploited this success through a series of raids, reached an agreement with the Meccans at Ḥudaybiyya (April 628), attacked and took the Jewish settlement of Haybar (May 628), conquered the oases of Fadak and Taymā.

In March 629, he went to Mecca to make the “Minor Pilgrimage,” granted by the agreement of Ḥudaybiyya concluded with the Meccans. “Henceforth, Muḥammad was the theocratic leader and he asserted himself as such.”●

Thus, he was “then obliged ‘to adopt a demeanour.’ Certain aspects of his life imposed constraints on him. His harem in particular which, after 627, increased to the size of that of a great emir. For him it was a cause for concern. Revelation then intervened to settle questions of precedence, to limit the number of co-wives, to curtail intrigues [...]. Similarly, special deference was due to his wives who, after him, could not have other husbands. Muḥammad was like the Patriarch of the Community and had to be honoured as such.”●

At the end of 629, Muḥammad denounced the truce of Ḥudaybiyya and marched on Mecca where he entered as victor. He destroyed the idols and gave solemn worship to Allāh in the Kaʿba built by Abraham.

THE DEMISE OF MUḤAMMAD

Muḥammad won another miraculous victory at Ḥunayn over a Bedouin confederation that was trying to stand up to him (late January 630). Then he made the Pilgrimage to Mecca and returned to Al Madīnah (March 630).

Heraclius, victorious over the Persians, was preparing to move south towards Yaṯrib to prevent a Muslim conquest of Syria. He was dissuaded “by his vision of the ‘victorious kingdom of a circumcised man,’ and by his conviction that this man was truly a divine Envoy.”●

Muḥammad, on the other hand, was “certain that God would open Syria to the armies of Islam”● and he prepared an expedition against the Byzantines. Thirty thousand men, including ten thousand horsemen set off under the leadership of Muḥammad himself. When they reached Tabūk, however, they turned back (October 630).

During the last two years of his life, the ninth and tenth of the Hijrah, Muḥammad received many emissaries from all over Arabia: delegates from repentant Ṭāʾif, Ḥimyarite princes from Yemen announcing their acceptance of Islam and rejection of polytheism, Christians from Najran eager to make a pact with the Prophet.●

In 632, year 10 of the Hijrah, Muḥammad personally led the ḥajj, the great pilgrimage to Mecca, for which he meticulously organised all the rites.● Then he prepared a campaign against the Arab tribes of Syria that were allied with Heraclius. He, however, fell ill and died in the arms of ʿĀʾiša.●

Such is the “Tradition” concerning the life of Prophet Muḥammad which, to this very day, Western science regards as historical.

HISTORY

The author of Sūrah 3 refers to himself as muḥammadun (verse 144). We have translated as “beloved” this derivative of the root ḥmd, the Arabic transcription of the biblical root ḥāmad, “to desire, to covet.” In Sūrah 1, ʾal-ḥamdu refers to “the love” that is owed “to the God Master of the centuries.”

A South Arabic inscription of Jamme gives the term mḥmd for the name of the “God of the Jews.”● Biella surely commits an anachronism by translating this divine name as “He who is the object of praise – the Praised One.” The obvious meaning of the expression designates “He who is the object of love – the “Beloved One,” a divine name par excellence. Sg 1:13-16 and passim.

Here, muḥammadun designates a man who is only an “oracle,” rasūlun, of the God and not God himself; as ʾîš ḥamudôt, “man of predilections,” designates Daniel the prophet in the Bible●.

In the context of Sūrah 3, the expression qualifies in the first place the “oracle” Jesus (Q 3:53 and sq.), a simple man, according to the aggadic part of the Sūrah (Q 3:33-59), and in the second place the author himself.

We have noticed how the author, although he was a great connoisseur of the Gospels, remains silent concerning the birth of “Jesus, son of Mary,” as well as on the events of His public life, His Passion, His death and His resurrection.

The author observes the same silence on himself, in the manner of Saint John who discreetly refers to himself in the third person, by the expression that muḥammadun seems to transpose into Arabic: “He whom Jesus loved.” Jn 13:23; Jn 19:26; Jn 20:2; Jn 21:7; Jn 21:20

If we restrict ourselves to what we have already studied – Sūrahs 1, 2 and 3, their scientific exegesis nevertheless provides us with some very reliable data.

THE AUTHOR

The author is the editor of Sūrah 1, an already ancient prayer, strictly Jewish, lacking any specifically “Muslim” character.

On the other hand, the prayer to “Our Master,” which concludes Sūrah 2, is his own composition (Q 2:286). This Sūrah in itself is nothing more than the account, in scriptural terms, of the events of 610-614. As a veritable rereading of divine revelation in the light of these events, this Sūrah is based on the authentic “Word,” ʾamr, of God (Q 2:109, Q 2:117, Q 2:210), expressed by the “luminous verses” of Biblical revelation (Q 2:211), which are recited (Q 2:129, Q 2:151, Q 2:252) and explained by the author on behalf of God himself (Q 2:219, Q 2:266; cf. Q 2:187, Q 2:221, Q 2:242) who communicates to him “understanding” of it (Q 2:99).

Thus, the author taught “writing,” kitāb (Q 2:129, Q 2:151), and “reading,” qurʾān (Q 2:185), to the children of Ishmael. This statement, repeated in Sūrah 3 (Q 3:164), is consistent with the advent of written Arabic, which can be determined by the comparative study of the epigraphic documents that have come down to us.

Blachère had also remarked: “The constitution and the development of written Arabic coincides so well, chronologically, with the introduction of monotheistic doctrines in the Arab domain that it is difficult not to see a mutual relationship between these two categories of facts.”●

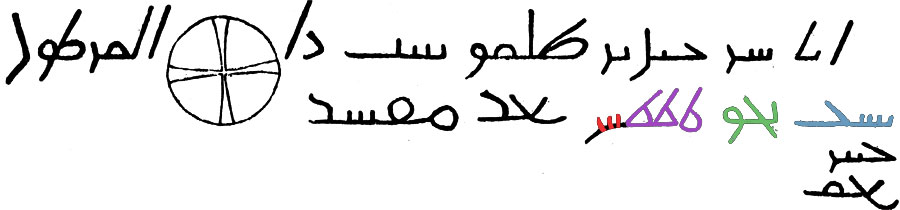

From the 6th century a.d. onwards, the ṯamūdéo-liḥyānite alphabet, derived from South Arabic (Fig. A [in the insert below]) was abandoned in favour of another system, derived from Aramaic writing (Fig. B and Fig. C), followed by the transition from this Aramaic cursive to the Arabic writing itself (Fig. D and Fig. E), of which Sūrah 1 constitutes the first literary witness.

The starting point of this evolution is well represented by the bilingual inscription of Umm-al-Jimāl (Fig.B), which can be dated to the end of the 3rd century a.d., and whose “script already constitutes a transitional stage towards Arabic writing,” Littmann observed. Many of the letters that are joined together in the Arabic alphabet, already appear here joined to the previous and following letters.”● Then the inscription of Namāra (Fig. C) is already “proto-Arabic.” It bears the explicit date of December 7, 328.

It was only in the 6th century, however, that a truly “Arabic” text appeared for the first time, with the inscription from Zabad (Fig. D), still in the same Syrian-Mesopotamian region. The end of the evolution seems definitively reached with the inscription from Harān (Fig. E), which bears the date of 568.

This new cursive is therefore derived from Nabataean writing, which itself appeared in about the 2nd century as “one of the variants of Aramaic writing. It is therefore a North Semitic script, itself derived from the Phoenician alphabet, which replaced a South Semitic script. The Nabataeans, judging by their proper names and some other remains, spoke an Arabic dialect, but they used, as a written language, Aramaic, the great commercial language of the Ancient Orient at that time, and they used a so-called Nabataean alphabet, which is only a cursive variant of the Aramaic alphabet.”●

As for Arabic, recently derived from ancient Nabataean, it does not appear as a “commercial language,” but above all as a religious language. The two inscriptions from Zabad and from Ḥarrān are Christian: Nau observed that “it is Christians above all who created alphabets for the peoples whom they converted and who taught them to read and write. The Arabic known as classical is no exception. Its alphabet is due to Christians, for it is among the Christian Arabs of Syria that we find the most ancient specimens of this writing.”●

The two inscriptions from Zabad and from Ḥarrān show in fact that in the 6th century Arabic language and writing were fixed and used in the Christian communities of Syria, together with Greek and Syriac. “It does not seem, however, that Arabic was used much, for it was in fact unreadable.”● This is what was going to change with the sudden emergence of the Qurʾān, the work of an incomparable genius.

As we have explained, in the genesis of the Arabic language and its written form, Sūrah 1, a Jewish prayer, finds its place, after the inscription from Ḥarrān, a Christian inscription dated 568. It is the first literary document attesting to the existence of a written and spoken Arabic language. It is succeeded by Sūrahs 2 and 3 (Fig. F), with their “specific Islamic coloration,” as Nöldeke would say, works of a certain muḥammadun, the object of divine favours.

FORMATION OF QURʾĀNIC SCRIPT AS WITNESSED

BY FOUR EPIGRAPHICAL MONUMENTS

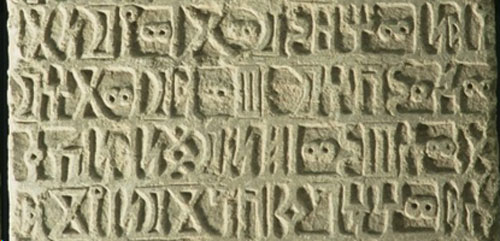

FIG. A. THE STELE OF ABRAHA, DATED 542.

The writing of the Arabs of the north of the Arabian Peninsula first derived from the rigid and unwieldy South Arabian alphabet characters, square in appearance. This fact is evidenced by the Liḥyānite inscriptions discovered in the ancient oasis of Dēdān, and the Ṯamūdéan discovered on the road from Taymā to Hēgra, dated from the 5th century. The Arabs of the north, however, would abandon this South Semitic script from the 6th century a.d. onwards, in favour of a cursive script, the genesis of which is illustrated by figures B to F.

For more details on the Stele of Abraha.

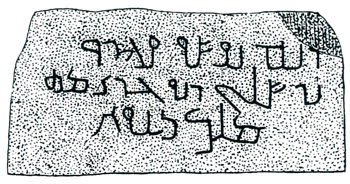

FIG. B. THE UMM-AL-JIMĀL INSCRIPTION, DATED FROM THE END OF THE 3rd CENTURY a.d.

The bilingual inscription of Umm-al-Jimāl represents the starting point of the evolution towards Arab writing. A North Semitic cursive script began to be adopted. It derived from Nabataean writing, which itself appeared in about the 2nd century as one of the variants of Aramaic writing. The Nabataeans spoke an Arabic dialect, but Aramaic was their written language. They used a so-called Nabataean alphabet which, in fact, was only a cursive variant of the Aramaic alphabet.

Its script already constitutes a transitional stage towards Arabic writing. Many of the letters that are joined together in Arabic, already appear here joined to the previous and following letters.

For more details on the Umm-al-Jimāl inscription.

FIG. C. THE NAMĀRA INSCRIPTION DATED 328 a.d.

It was discovered on a basalt lintel east of Djebel el-Druze. Compared to the Umm-al-Jimāl inscription (above), the Namāra inscription shows a significant evolution of the Nabataean characters towards an Arabic script. The ligatures are more numerous than in the Umm-al-Jimāl: (reading from right to left) the shin is linked on the right to the letter that precedes it, and the yod on the left to the letter that follows it. Furthermore, the letters are rounder in shape. The samech has disappeared, as seen in the word kšlūl (line 5), Aramaic name for the month of kisleu, corresponding to December. Already we distinguish the lām alif (line 2), on the word ʾlʾšdīn: it is a lamed placed on a Nabataean aleph.

For more details on the Namāra inscription.

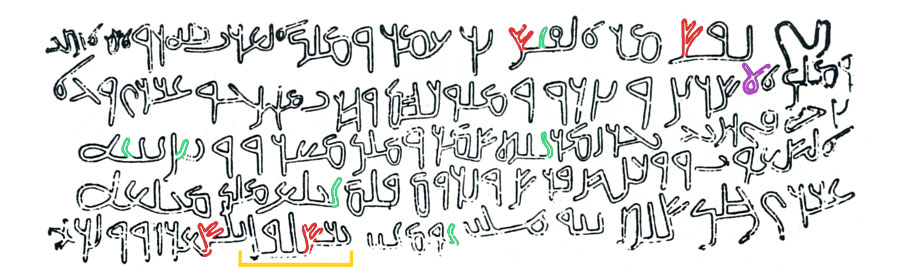

FIG. D. THE ZABAD INSCRIPTION DATED 512 a.d.

It was found on the lintel of the gate of a basilica dedicated to Saint Sergius in the midst of the Roman ruins in Zabad. Most of the letters have approximately the form that characterise, a hundred years later, Qurʾānic writing. The alif is reduced to a vertical bar (line 1). The lām alif is purely Arabic, as well as the sin. The beth and the taw are becoming undistinguishable.

For more details on the Zabad inscription.

FIG. E. THE HARĀN INSCRIPTION DATED 568 a.d.

The Arabic part of a Greek-Arabic inscription found in Harān, Syria, north-west of Djebel el-Druze, on the lintel of the Martyrium Saint John the Baptist. “Martyrium,” is designated here explicitly in Arabic by the last two words of the first line (on the left because Arabic is read from right to left): dā l-mrtūl, “this martyrium.” These two words are on either side of the Greek cross with flared arms inscribed within a circle.

The first word of line 2, composed of the letters snt, means “year.” It is followed by Nabataean symbols that are used in the notation of numbers: First the symbol for 4 followed by the sign of hundreds, then three times the sign 20 and finally three bars of unity.” Thus: year 463 of Bosra, which is year 568 of our era.

For more details on the Harān inscription.

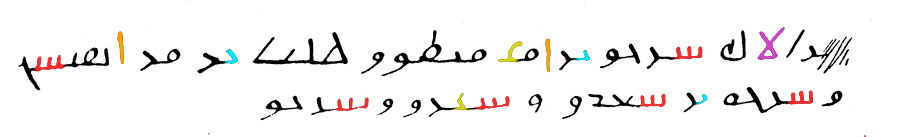

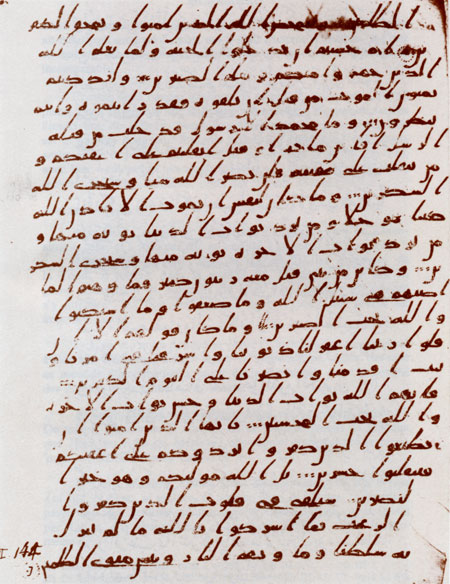

FIG. F. THE QURʾĀNIC SCRIPT. Manuscript “Arab 328,” folio 6, verso (Q 3:141-151).

Excerpt from an anonymous and undated fragmentary copy of the Qurʾān. Almost all the critics, however, hold it to be the most ancient existent copy.

A simple comparison of the Harān inscription (above) with the manuscript ‘Arabic 328’ (below) reveals a striking resemblance between the letters engraved on the lintel and those traced on the parchment: the same slanting of the upstrokes; the same stiff and angular writing, an ornamental appearance, corresponding to an awkward written form. This confirms that the writing known as Kufic, which was thought to have been be invented in the city of Kufa after Islamism, was in reality in existence as early as 568 a.d.

APOSTLE

“The God” having “sent down Scripture” (Q 3:7) upon this “beloved,” he received through it “the Torah and the Gospel” as his share. (Q 3)

Since he already enumerated the requirements of the Torah in Sūrah 2, the author preaches the Gospel in Sūrah 3. He does so as a great connoisseur and imitator of Saint Paul, as might be expected.● The list of connections with the Apostle is impressive:

1° Both give Jesus the Messianic “appellation” that Jesus Himself shunned before His Resurrection, but which, after Pentecost, became His second denomination on the lips of the Apostles: “Christ,” ʾal-masīḥ (Q 3:45). Cf. Rm 1:1; Rm 6:3-4; Rm 6:8-9; Rm 6:11; Ga 5:24 and passim; Cf. Ac 2:38; Ac 3:6; Ac 3:18; Ac 3:20; Ac 5:42; cf. The Stele of Abraha.)

2° According to the Epistle to the Galatians, Jesus was “born of a woman.” Ga 4:4; Likewise, the author of Sūrah 3 never misses an occasion to recall that Jesus is the “son of Mary” (Q 3:45; cf. Q 2:87; Q 2:253), Who is designated by the term ʾunṯā, “woman,” from Her birth (Q 3:36).

3° In the same Epistle, Saint Paul declares that there is “neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor freeman, there is neither male nor female,” for you are all one “in Christ Jesus.” If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to promise.”●

In the same way, the author of Sūrah 3 declares that he makes no distinction between “Abraham, Ishmael, Isaac, Jacob and the tribes,” no more than between “Moses, Jesus and the prophets” (Q 3:84).

Firstly, to make no “distinction” between Ishmael and Isaac amounts to appropriating the whole of Judaism on behalf of the Arabs, Ishmael’s descendants. Secondly, to make no distinction between Moses and Jesus by means of a truncated genealogy, which abolishes the distances between generations (Q 3:33 sq.;)● amounts to abolishing the “distinction” between the Old and the New Testament, between the Judaism that has just been transferred to Ishmael’s descendents, and Christianity.

Thus the whole Bible finds itself reduced to a single “covenant,” the one that God made with Abraham and Ishmael (Q 2:125; cf. Q 2:62).

4° Saint Paul is conscious of being the apostle of God and the successor of the prophets. These were the men of the Word: he too has been chosen to announce the good news 1 Th 1:2-4; 2 Th 1:10.

The author of Sūrahs 2 and 3 likewise is conscious of being the oracle of God (Q 2:151; Q 3:144, Q 3:164). The successor of Moses and Jesus (Q 2:67-73, Q 2:136, Q 2:151-153; Q 3:84), he has been chosen, “object of predilection” (Q 3:144), to announce the “good news” (Q 2:97, Q 2:119; Q 3:126) of the fulfilment of the promises made to Abraham (Q 2:127).

He did so with a confidence that comes from God, like Saint Paul 1 Th 2:2; (Q 3:159).

Both perform this ministry solely for the sake of pleasing God, 1 Th 2:4; (Q 3:162; cf. Q 3:174) without seeking their own glory from men, 1 Th 2:6; (Q 3:190) in the “weakness” 2 Co 12:9-10; (Q 3:144) revealed by the failure of 614.

WARLORD

The first corollary of this return to the Old Testament is holy war (Q 2:190 sq; cf Q 2:154-157) for the conquest of Jerusalem (Q 2:208) and the restoration of the “House,” ʾal-bayt, the “Place of Abraham,” maqāmu ʾib’rāhīma (Q 2:125 sq.; Q 2:144; cf. Q 3:96-97), in order to make a “pilgrimage,” ḥijju (Q 2:196 sq.; cf. Q 2:158 sq.; Q 3:97), there, and to restore the Kingdom of God (Q 2:243 sq.; Q 3:97).

It is to this end that the author, like Abraham “left his tent” (Q 3:121) and “stationed the faithful for combat.” As the leader of a Saracen expedition that joined the Judeo-Persian coalition of 614, the author, like a new Joshua, led the children of Ishmael to the conquest of the “Country” (Q 2:11; cf. Q 2:168) to the “gates of the God:” ʾaṣ-ṣafā and ʾal-marwat (Q 2:158; cf. Q 2:189). They “swept down from Arabia,” (Q 2:198) and entered into Jerusalem (Q 2:208). Like a new David, the author, at first victorious, thwarted the desire for universal domination of both the Jews and the Christians (Q 3:151-152), not, however, without reviving the great theocratic politics of Isaiah and its universalism (Q 3:20, Q 3:28), but in order to subjugate the world to the children of Ishmael.

The first advance of this victorious conquest was stopped and transformed into a veritable “calvary,” qarḥun, (Q 3:140, Q 3:172) as a result of the traps set (Q 3:99), the betrayals fomented (Q 3:122, Q 3:152) by the perfidy of false brethren, the children of Israel (Q 3:118-119). Furthermore, murmurs rose in the ranks of the children of Ishmael themselves (Q 3:152). Finally, the latter were “dispersed” (Q 3:123) and “expelled” (Q 3:195).

It was then that the author, far from abandoning his great design, wrote Sūrah 3 to strengthen the courage of the “hesitants” by means of this “Writing” (Q 3:7-9), drawing from the very failure a promise of a “restoration,” of a definitive “return” (Q 3:145; cf. Q 3:124-129), in the same way that Jesus, in the Gospel, always placed after the announcement of His Passion and death, that of His resurrection; or again in the manner of Saint Paul who drew all his strength from his very “weakness” (Q 3:144). 2 Co 12:10;

Sūrah 3 takes place during this historical period that covers the years from 614 to 638 A.D., between the defeat and the victory of a party of Arabs of whom the author indeed seems to have been the oracle and the leader. What follows will reveal more to us.

“BELOVED”

Henceforth, can we go even further? The contacts with the Gospel, announced incidentally in verse 3, are so precise and numerous throughout Sūrah 3 that Father Georges de Nantes does not hesitate to discern in the thought of the author, beyond the clear will to imitate Saint Paul, the thinly veiled intention of taking the place of Jesus Himself. Verse 144, in which the author lays claim to the divine name muḥammadun, misunderstood by the commentators and unduly interpreted as a proper noun, definitively reveals this ambition and marks the summit of the Sūrah.

Palestinian idyll

The author has the Gospel, ʾal-ʾinjīl, “in his hands.” It is not only a “Way” but also a “Redemption” descended from heaven, just like the “Torah,” ʾat-tawrāt. There is no distinction, much less opposition, between the “verses of God” coming from one or the other (verse 3-4).

For instance, there are expressions resembling those of the fourth Gospel: “It is for the God that I myself am perfect, with him who seeks me” (verse 20). Also: “If you love the God, seek me. The God will love you” (verse 31). The author, however, is drawing attention to himself, substituting himself for Christ and attributing to himself His words and His power of intercession.

He also has the Synoptic Gospels in mind with the announcement of the “Kingdom,” ʾal-mulk, of the “Elohim” ʾal-llahum (verse 26), which he makes his own.

Thereafter follows the aggadah that we translated under the title: “The Sign of Jesus, Son of Mary” (verses 33-59). The author endeavours to keep in the background. He presents the character of Jesus. Yet his presentation is reductive, as we have said: “Son of Mary” effaces the divinity and Messiahship of Christ contained in the expressions “Son of the Most High” and “Son of David.” Father Georges de Nantes adds: “Son of Mary” also effaces the divine name of “Son of Man,” by which Jesus meant that He descended from Heaven. Mt 8:20; Mt 24:30; cf. Dn 7:13 In short, this aggadah creates a “vagueness,”● as Jomier and Abd-el-Jalil say, transforming the life and teachings of Jesus into a kind of evanescent myth, yet figurative of what is to come.

For “the Gospel,” ʾal-ʾinjīl, continues. Or rather, it suddenly regains historical consistency. “Go up!” taʿālaw (verses 61, 64). The author comes back into the picture. He substitutes himself for Jesus “ascending to Jerusalem.” Lk 19:28; cf. Lk 9:51; Lk 13:22; Lk 17:11 Like Jesus he was to engage in a terrible controversy about Abraham (verses 65-68) Jn 8:31-59. Each verse is woven with evangelical reminiscences. There can be no doubt: after the substitution of the Old Testament of Ishmael for that of Israel carried out in Sūrah 2, now we have the substitution of the life and teachings of the new Master and Saviour, the author himself, for the Gospels and other writings of the New Testament. He elaborates the myth of Jesus, the prophet, son of Mary, pure “announcement” of the One who would one day come as heir to the “perfect” religion, of Abraham, as a reformer of the “entangled” religions of Jews and Christians.

The “Calvary” of the “Beloved”

He has reached Jerusalem where the “House of Bakka” (verse 96) is found. There he is to suffer a failure “by a dispersion,” bi-badrin (verse 123) which takes exactly the place of the Gospel accounts narrating the failures of Jesus in Galilee and Jerusalem.

In Galilee, after the discourse on the Bread of Life: “After this, many of his disciples drew back and no longer went about with Him.”● In Jerusalem, after the ephemeral triumph of the Palm Sunday, he was betrayed by one of His own, handed over to His enemies and crucified in the “place of Calvary (a skull),”● after having three times prepared His disciples for this tragic ordeal by an explicit announcement Mt 16:21; Mt 17:22-23; Mt 20:17-19. But, to sustain their courage, He was transfigured before them. Then they heard a voice in the luminous cloud, saying: “This is My beloved Son, with Whom I am well pleased; listen to Him.”● This was not the first time. Already on the day of his enthronement, at the moment of entering His public life: “He saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove, and alighting on Him; 17 and there, a voice from Heaven, saying: ‘This is My beloved Son, with Whom I am well pleased.’”●

With italics we draw attention to the words “like” and “beloved” that we find in Sūrah 3 (verses 49 and 144). “Beloved” expressed by the noun muḥammadun, after the mention of “Calvary,” qarḥun,● agrees not only with the two theophanies – related by the Synoptics Gospels –, which we have just mentioned, but also with the deepest Johannine theology, according to which the divine glory of the Son of God, His Transfiguration appears on “Mount Calvary,” even better than on Mount Thabor.●

This is exactly the meaning of verse 144 of Sūrah 3. The author joins the glorious assurance of being the object of divine favours, muḥammadun, “beloved,” to a justification of his “weakness,” his vulnerability, revealed by the failure of 614. This verse also contains an announcement of the author’s possible death, at least of a cruel trial for the faith of his disciples.

The third part of the Sūrah is a kind of eschatological discourse, a promise of “resurrection,” in the form of a revenge of the children of Ishmael going back to the conquest of Jerusalem, and this time victoriously (verses 151-178).

By the epithet of muḥammadun, the author thus declares himself “beloved,” object of the favour of the “Circumciser” mawla, whose predilections in favour of the children of Ishmael were revealed in Sūrah 2 (Q 2:286; Q 3:150; cf. Q 3:119).

This is why Father Georges de Nantes proposes to entitle Sūrah 2: “The Circumciser,” and Sūrah 3: “Beloved.”

Gaudefroy-Demombynes, Mahomet, Albin Michel, 1957, p. 4. Rodinson republished a paperback edition of this “comprehensive survey” (1969)

Régis Blachère, Le problème de Mahomet. Essai de biographie critique du fondateur de l’Islam, P.U.F., 1952, p. 5.

Maxime Rodinson, Mahomet, Seuil, 3rd ed., 1974, p. 67.

Régis Blachère was a French orientalist, Arabist and Islamic scholar (1900-1973). He held the Arab Philosophy Chair at the Sorbonne and was the director of the Institute of Islamic Studies (Institut des études islamiques) in Paris. He published a history of Arabic literature (1952), a study on the problem posed by Muḥammad (1952), a translation of the Qurʾān (1950 and a new version in 1957), and an introduction to the Qurʾān (1959). He also co-authored a grammar of classical Arabic with Gaudefroy-Demombynes. Throughout his analysis, Brother Bruno refers to Régis Blachère’s translation of the Qurʾān, along with Denise Masson’s, for they are the only recent translators who show some concern for critical methods. Blachère and Masson will only serve Brother Bruno occasionally to emphasise the inconsistencies and contradictions of the “accepted meaning.” He does not systematically compare his exegesis with theirs. You will come to understand how totally pointless this would be as you advance in Brother Bruno’s commentary.

Régis Blachère was a French orientalist, Arabist and Islamic scholar (1900-1973). He held the Arab Philosophy Chair at the Sorbonne and was the director of the Institute of Islamic Studies (Institut des études islamiques) in Paris. He published a history of Arabic literature (1952), a study on the problem posed by Muḥammad (1952), a translation of the Qurʾān (1950 and a new version in 1957), and an introduction to the Qurʾān (1959). He also co-authored a grammar of classical Arabic with Gaudefroy-Demombynes. Throughout his analysis, Brother Bruno refers to Régis Blachère’s translation of the Qurʾān, along with Denise Masson’s, for they are the only recent translators who show some concern for critical methods. Blachère and Masson will only serve Brother Bruno occasionally to emphasise the inconsistencies and contradictions of the “accepted meaning.” He does not systematically compare his exegesis with theirs. You will come to understand how totally pointless this would be as you advance in Brother Bruno’s commentary.

Régis Blachère, Le problème de Mahomet. Essai de biographie critique du fondateur de l’Islam, P.U.F., 1952, p. 5.

Régis Blachère, Le problème de Mahomet. Essai de biographie critique du fondateur de l’Islam, P.U.F., 1952, p. 7.

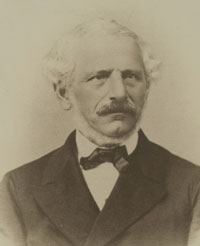

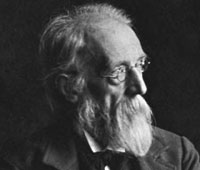

Gustav Weil (1808-1989) was born in Sulzbuig, Baden, to a rabbinical family. Like his forebears, he was to have been a rabbi, and he studied Talmud under his grandfather at the Talmudic School in Metz. He, however, abandoned this at the first opportunity, entering the University of Heidelberg at the age of twenty. There he studied philology and history, as well as Arabic. In 1830, he went to Paris to study under Silvestre de Sacy, and from there he accompanied the French forces which occupied Algeria, as a correspondent for an Augsburg newspaper. In 1831 he proceeded to Cairo, where he spent more than four years teaching French at the new Egyptian medical school. In Egypt he perfected his Arabic and acquired Turkish and Persian.

Gustav Weil (1808-1989) was born in Sulzbuig, Baden, to a rabbinical family. Like his forebears, he was to have been a rabbi, and he studied Talmud under his grandfather at the Talmudic School in Metz. He, however, abandoned this at the first opportunity, entering the University of Heidelberg at the age of twenty. There he studied philology and history, as well as Arabic. In 1830, he went to Paris to study under Silvestre de Sacy, and from there he accompanied the French forces which occupied Algeria, as a correspondent for an Augsburg newspaper. In 1831 he proceeded to Cairo, where he spent more than four years teaching French at the new Egyptian medical school. In Egypt he perfected his Arabic and acquired Turkish and Persian.

After some months in Istanbul, he returned to the University of Heidelberg, where he served as a librarian for almost twenty-five years. In 1843, Weil published a life of Muhammad entitled Mohammed der Prophet. It was the first Western biography of Muhammad that was free from prejudice and polemic. It was based on a profound yet critical knowledge of the Arabic sources. For the first time, he gave the European reader an opportunity to see Muḥammad as the Muslims saw him. Weil achieved this through an exacting and exhausting use of manuscripts then available in Europe. Although trained in philology, Weil came to regard himself as a historian of Islam. From 1846 to 1862, Weil published the first complete history of the Egyptian and Spanish caliphates, written according to the demands of European criticism and composed from the original sources. Weil reproduced the narrative style of his Arabic sources, resulting in an account that was neither dramatic nor analytical. In 1861, Weil was given a professorship at the university.

Gustav Weil’s contribution to the foundation of early Islamic studies is not always given recognition. For instance, Theodor Nöldeke’s prize-winning dissertation on the Qurʾān owes a substantial debt to Weil’s earlier work on the topic, yet it is Nöldeke, rather than he, who is remembered as the great father of Qurʾānic studies.

Leone Caetani (1869-1935) was an Italian orientalist, historian and Member of Parliament. Born into the ancient aristocratic family of Rome, he studied classical history at La Sapienza University, presenting in 1891, a thesis on a papal legation in Paris. However, he became fascinated with the Orient at an early age and made a number of journeys there. His most important journey took place in 1894 from Egypt to Persia. At La Sapienza, he also attended courses in Arabic language and literature, and in Semitic languages. He soon mastered several oriental languages, including Arabic, Turkish and Persian. He participated in his first international congress of orientalists in London in September 1892. Thanks to the family fortune, he was able to build up a rich library on Arab-Muslim civilisation, including a remarkable collection of photographs of manuscripts.

Leone Caetani (1869-1935) was an Italian orientalist, historian and Member of Parliament. Born into the ancient aristocratic family of Rome, he studied classical history at La Sapienza University, presenting in 1891, a thesis on a papal legation in Paris. However, he became fascinated with the Orient at an early age and made a number of journeys there. His most important journey took place in 1894 from Egypt to Persia. At La Sapienza, he also attended courses in Arabic language and literature, and in Semitic languages. He soon mastered several oriental languages, including Arabic, Turkish and Persian. He participated in his first international congress of orientalists in London in September 1892. Thanks to the family fortune, he was able to build up a rich library on Arab-Muslim civilisation, including a remarkable collection of photographs of manuscripts.

He also conceived very early on what was to become his magnum opus: a meticulous analytical history, year by year, of the early days of Islam from the Hijrah in 622 to the death of the Caliph Ali ibn Abi Talib in 661 (year 40 of the Hijrah). Caetani collected as exhaustively as possible all the “historical” material transmitted by ancient authors, and treated it by the critical methods of modern science. The result was the Annali dell’ Islam, a monumental ten volume work, published between 1905 and 1926. Caetani conceived and began this great work alone, but later enlisted the help of collaborators.

In 1919 he became a full member of the Academy of the Lynceans (of which he had been a correspondent since 1911), but he did not really return to his work on the Annali dell’ Islam, which he had planned to continue until the fall of the Umayyads in 750. In 1924 he created a Fondazione Caetani per gli studi musulmani at the Academy of the Lynceans, to which he bequeathed his splendid orientalist library, and of which he had initially planned to become active president. His notorious opposition to fascism led him to leave Italy for Canada in 1927. He acquired a property in Vernon in the Vancouver hinterland, where he led a secluded and rustic life, interspersed with brief stays in France and England. Having adopted Canadian citizenship, he was stripped of his Italian nationality by the Fascist regime in April 1935, and thereby disbarred from the Academy of the Lynceans a few months before his death.

Caetani, Annali dell’Islam, quoted by Blachère (Le problème de Mahomet. Essai de biographie critique du fondateur de l’Islam, P.U.F., 1952, p. 9).

Maxime Rodinson, Mahomet, Seuil, 3rd ed., 1974, p. 12

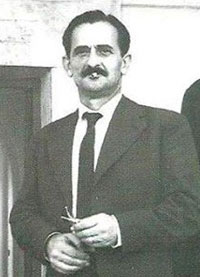

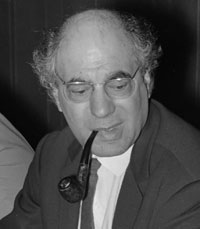

Maxime Rodinson (1915-2004) was linguist, sociologist, ethnologist and philosopher. He was born in Paris into a family of Russian-Polish immigrants who had settled in France at the end of the 19th century. Although he spent his childhood in a family climate – that of the Ashkenazi milieu of Central European Yiddish-speaking Jews –, his parents were irreligious internationalists who instilled in their child the ideas of the Enlightenment and secular and republican values. His proletarian parents were active in the Socialist Party, then in the new Communist Party in 1920.

Maxime Rodinson (1915-2004) was linguist, sociologist, ethnologist and philosopher. He was born in Paris into a family of Russian-Polish immigrants who had settled in France at the end of the 19th century. Although he spent his childhood in a family climate – that of the Ashkenazi milieu of Central European Yiddish-speaking Jews –, his parents were irreligious internationalists who instilled in their child the ideas of the Enlightenment and secular and republican values. His proletarian parents were active in the Socialist Party, then in the new Communist Party in 1920.

Rodison received an ordinary primary education. At 14 years of age, he began working as a messenger to earn a living. At the same time he undertook to study alone in order to take the competitive entrance examination for the École des langues orientales, which he passed in 1932. He plunged into academic work with meticulous passion and a rigour. The learning of Arabic, Hebrew and Aramaic testifies to his interest in Semitic languages and in comparative linguistics (he approached some thirty languages), but it was Ge’ez, the ancient Ethiopian language, which became his specialty.

Mobilised at the beginning of the Second World War, he asked to be sent to Syria to put into practice what he had learned at the School of Oriental Languages. From Syria, he was soon sent to Lebanon. After being demobilised, he managed to find various jobs there. He eventually returned to France after is application to the French Institute of Damascus was not accepted, because of his membership in the Communist Party.

Upon his return to France, he found a job at the National Library, where he was assigned to the Department of Oriental Prints. In 1955, he began a career as an academic at the École Pratique des Hautes Études, where he taught Ge’ez and the historical ethnography of the Near East for more than forty years.

His work includes nearly a thousand articles for scientific publications as well as for the press, and numerous works accessible to a wide audience. His books can be grouped into three categories, those devoted to the Arab-Islamic world, those dealing with the Jewish people and Israel, and general works.

At the instigation of a friend, he wrote a biography of Muḥammad, applying to this work the methodological approach of the social sciences. Published in 1961, the book that made him known to the general public.

Maxime Rodinson, Mahomet, Seuil, 3rd ed., 1974, p. 14

Régis Blachère, Le problème de Mahomet. Essai de biographie critique du fondateur de l’Islam, P.U.F., 1952, p. 10

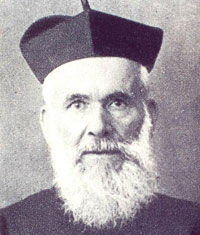

Father Henri Lammens (1862–1937) was a prominent Flemish Belgian-born Jesuit and Orientalist of Saint Joseph’s University in Beirut, Lebanon. He was the first to venture applying the rules of the modern historical and critical method to the Qurʾān. Father Lammens based his work on the Professor Ignác Goldziher concerning the historical value of the Tradition. He adopted Goldziher’s viewpoint and pursued the inquiry. Lammens’ conclusions are firm and represent a considerable advance over Goldziher’s. The latter had shown the profoundly “tendentious character” of the Tradition. Father Lammens showed its “apocryphal” nature. He positively demonstrated that the ḥadīṯs are nothing but pure inventions, that the so-called ‘eyewitnesses,’ the authorities of the Ḥadīṯ, are fictitious. Thus, the Sīrah has no historical basis other than the Qurʾān, of which it is nothing more than an imaginary elaboration: “Since the Tradition arises from the affirmations recorded in the Qurʾān,” Father Lammens stated, “it does not provide a verification or complementary information, but an apocryphal elaboration.” He was therefore able to conclude that “the Sīrah remains to be written, just as the historical Muḥammad remains to be discovered.” To do this he advocated rejecting the ‘Tradition’ in its totality, replacing its fanciful exegesis by a scientific exegesis. Although he recommended this, he never carried out this work. When Father Lammens passed away, the Jesuits of Beirut put his works under seal, and since then it has been a law of Islamology to ignore his discoveries.

Father Henri Lammens (1862–1937) was a prominent Flemish Belgian-born Jesuit and Orientalist of Saint Joseph’s University in Beirut, Lebanon. He was the first to venture applying the rules of the modern historical and critical method to the Qurʾān. Father Lammens based his work on the Professor Ignác Goldziher concerning the historical value of the Tradition. He adopted Goldziher’s viewpoint and pursued the inquiry. Lammens’ conclusions are firm and represent a considerable advance over Goldziher’s. The latter had shown the profoundly “tendentious character” of the Tradition. Father Lammens showed its “apocryphal” nature. He positively demonstrated that the ḥadīṯs are nothing but pure inventions, that the so-called ‘eyewitnesses,’ the authorities of the Ḥadīṯ, are fictitious. Thus, the Sīrah has no historical basis other than the Qurʾān, of which it is nothing more than an imaginary elaboration: “Since the Tradition arises from the affirmations recorded in the Qurʾān,” Father Lammens stated, “it does not provide a verification or complementary information, but an apocryphal elaboration.” He was therefore able to conclude that “the Sīrah remains to be written, just as the historical Muḥammad remains to be discovered.” To do this he advocated rejecting the ‘Tradition’ in its totality, replacing its fanciful exegesis by a scientific exegesis. Although he recommended this, he never carried out this work. When Father Lammens passed away, the Jesuits of Beirut put his works under seal, and since then it has been a law of Islamology to ignore his discoveries.

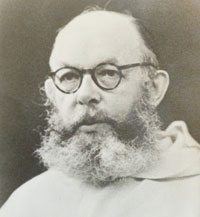

Father Gabriel Théry (1891-1959), Dominican, must be considered the founder of “the scientific exegesis” of the Qurʾān. Historian, theologian et author, Doctor of theology, professor at Saulchoir and at the Institut catholique de Paris, he was consultor for the Historic Section of the Congregation of Rites. He was a reputed medievalist in the scientific research community. In 1926, he co-founded with Étienne Gilson the Archives d’Histoire Doctrinale et Littéraire du Moyen Âge (ahdlma). In 1955, he self-published under the pseudonym Hanna Zakarias the first two volumes of his work, De Moïse à Muḥammad. A third volume was published posthumously in 1963. His forth volume remains unpublished. It was Father Théry's brilliant contribution to have understood that it was necessary to begin by comparing the Qurʾān to the Bible. He succeeded in solving the very difficult question of the literary genres of the sūrahs of the Qurʾān. He distinguished three series of texts: a Prayer of Praise, Sūrah I; a dogmatic book of which only fragments remain, which he called the Corab; finally a history book, a true chronicle, which he called the Book of the Acts of Islam.” His monumental work became known to a great extent through the reviews that Father de Nantes wrote on it to stimulate a debate. He wrote: “Hanna Zakarias had the freedom of mind to read the Qurʾān as a document of the past and to seek to explain it by the simplest laws of the historical method.” The inspired intuition that occurred to Father Théry was that the author of the Qurʾān used the Hebrew language to give a religious vocabulary to the Arabs.

Father Gabriel Théry (1891-1959), Dominican, must be considered the founder of “the scientific exegesis” of the Qurʾān. Historian, theologian et author, Doctor of theology, professor at Saulchoir and at the Institut catholique de Paris, he was consultor for the Historic Section of the Congregation of Rites. He was a reputed medievalist in the scientific research community. In 1926, he co-founded with Étienne Gilson the Archives d’Histoire Doctrinale et Littéraire du Moyen Âge (ahdlma). In 1955, he self-published under the pseudonym Hanna Zakarias the first two volumes of his work, De Moïse à Muḥammad. A third volume was published posthumously in 1963. His forth volume remains unpublished. It was Father Théry's brilliant contribution to have understood that it was necessary to begin by comparing the Qurʾān to the Bible. He succeeded in solving the very difficult question of the literary genres of the sūrahs of the Qurʾān. He distinguished three series of texts: a Prayer of Praise, Sūrah I; a dogmatic book of which only fragments remain, which he called the Corab; finally a history book, a true chronicle, which he called the Book of the Acts of Islam.” His monumental work became known to a great extent through the reviews that Father de Nantes wrote on it to stimulate a debate. He wrote: “Hanna Zakarias had the freedom of mind to read the Qurʾān as a document of the past and to seek to explain it by the simplest laws of the historical method.” The inspired intuition that occurred to Father Théry was that the author of the Qurʾān used the Hebrew language to give a religious vocabulary to the Arabs.

Bertram Johannes Otto Schrieke (1890-1945) was a Dutch anthropologist and sociologist. He studied at the University of Leiden, where he obtained a doctor’s degree in “languages and literature of the East Indian archipelago.” He then studied sociology at the University of Amsterdam.

Bertram Johannes Otto Schrieke (1890-1945) was a Dutch anthropologist and sociologist. He studied at the University of Leiden, where he obtained a doctor’s degree in “languages and literature of the East Indian archipelago.” He then studied sociology at the University of Amsterdam.

Schrieke was not a theorist. Rather he took exception to existing theories as being too one-sided or too narrow. He held the view that “a culture forms an organic whole, which cannot be split up into different parts as if these components had no relation to each other.” As demonstrated by his lifelong work in the social and economic aspects of the history of Indonesia, at that time a Dutch colony, Schrieke’s forte lay in maintaining a critical attitude toward the generally accepted approaches to these subjects, which relied on archaeology and colonial history.

In his doctoral thesis, (1916), he analysed the text of a manuscript, written in Javanese and ascribed to a legendary Muslim saint. His study of this manuscript, as well as of the early history of the Portuguese and Dutch trade contacts with Indonesia and of the published material on the voyages of Chinese and Arabs in the previous centuries, enabled him to revise the existing theory that the Islamisation of the archipelago had come about pacifically. He came to the conclusion that Islamisation, hitherto considered to be primarily the product of trade relations, had been equally influenced by political conflicts and military struggles. Schrieke suggested that it is “impossible to understand the spread of Islam in the archipelago unless one takes into account the antagonism between the Muslim traders and the Portuguese.”

During the 1920s, when Schrieke was acting as adviser on native and Arab affairs to the Netherlands Indies government, he was called upon to conduct an inquiry into the communist uprisings on the west coast of Sumatra in 1926. In order to explain the success of the communists’ tactics, Schrieke incorporated in his report facts relating to the historical background and structure of society. He was thus able to point to the factors in this transitional period which had helped to foster the antigovernment attitude of the population. Here again his natural approach was to gather any relevant data, including the seemingly unimportant and the controversial.

When he was professor of sociology in the law school at Batavia, from 1924 to 1929, and later at the University of Amsterdam, from 1936 to 1945, Schrieke’s exerted influence in sociology and history. He fostered surveys of research on both Indonesia and the Netherlands Caribbean territories. Schrieke died suddenly in London in September 1945 while attending a United Nations conference as a Netherlands government delegate on Indonesian affairs.

Josef Horovitz (1874-1931) was a German Orientalist, and son of a prominent orthodox rabbi. Educated in Frankfurt, he studied at the University of Berlin with Edward Sachau, where he also began to teach. In 1905-1906, he travelled through Turkey, Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, on commission to find Arabic manuscripts. From 1907 to 1914, he lived in India, where he taught Arabic at the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College in Aligar. He also served as the curator of Islamic inscriptions for the Indian government. Due to his German nationality, he lost these positions at the beginning of the First World War.

Josef Horovitz (1874-1931) was a German Orientalist, and son of a prominent orthodox rabbi. Educated in Frankfurt, he studied at the University of Berlin with Edward Sachau, where he also began to teach. In 1905-1906, he travelled through Turkey, Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, on commission to find Arabic manuscripts. From 1907 to 1914, he lived in India, where he taught Arabic at the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College in Aligar. He also served as the curator of Islamic inscriptions for the Indian government. Due to his German nationality, he lost these positions at the beginning of the First World War.

In 1914, he was appointed to profess Semitic languages at the University of Frankfurt, where he would teach until his death. His range included early Islamic history, early Arabic poetry, Qur’anic studies, and Islam in India. Horovitz produced an amazing number of outstanding students during his rather brief tenure at Frankfurt, and his influence upon all of them was strong. He was a very reserved man, but when set talking he was an inexhaustible source of knowledge about the East, past and present, and a paragon of philological exactitude. In the 1920s, as a member of the board of trustees of Hebrew University in Jerusalem from its inception, Horovitz created the department of Oriental studies, became its director in absentia, and initiated its collective project, the concordance of early Arabic poetry. At first Horovitz devoted himself to the study of Arabic historical literature and then to early Arabic poetry. His major work was a commentary on the Qurʾān, which he did not complete. He was not a fervent Zionist, and his political sympathies lay with Brit Shalom, the intellectual movement, comprised largely of German Jews, that abjured a Jewish state. Nevertheless, he gave crucial scholarly legitimacy to a fledgling organisation in Jerusalem, which would later provide a haven for many of the Jewish refugee scholars fleeing Nazi Germany.

Horovitz is best known for his study: The Earliest Biographies of the Prophet and Their Authors, published in 1927 It is the first comprehensive work on the early accounts of Muhammad’s life making full use of the available sources. It traces the emergence and growth of the Sīrah tradition from the generation of Muslims following the Prophet’s death down to the biographical dictionary of Ibn Sa’d in the 9 century, and thus covers many of the most important developments in the formative stage of Arab-Islamic tradition. Horovitz examined relations between Islam and Judaism in his Jewish Proper Names and Derivatives in the Qurʾān.

Theodor Nöldeke (1836-1930) was a German orientalist. He studied in Göttingen, Vienna, Leiden and Berlin. Along with Ignaz Goldziher, he is considered the founder of modern Islamic studies in Europe. In 1859 his history of the Qurʾān won for him the prize of the French Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, and in the following year he rewrote it in German (Geschichte des Qorâns). Nöldeke admitted: “In the end, I renounce exploring the mystery of the historical personality of Muḥammad.” Nöldeke is best known for his reordering of the 114 Sūrahs of the Qurʾān to match what he considered to be their true historical occurrence. Nöldeke based this work on the sequence of revelation with the development of content and the origination of new linguistic styles. The Nöldeke Chronology divides the Sūrahs of the Qurʾān are into four groupings: the First Meccan Period, the Second Meccan Period, the Third Meccan Period, the Medinese Period. Nöldeke considered this arrangement to be more coherent and comprehensive. Despite this attempt made by Noldëke, and later on by Schwally, Blachère, etc., Brother Bruno believes that there is no reason to give the “Sūrahs” an order different from the one found in the accepted “vulgate.”

Theodor Nöldeke (1836-1930) was a German orientalist. He studied in Göttingen, Vienna, Leiden and Berlin. Along with Ignaz Goldziher, he is considered the founder of modern Islamic studies in Europe. In 1859 his history of the Qurʾān won for him the prize of the French Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, and in the following year he rewrote it in German (Geschichte des Qorâns). Nöldeke admitted: “In the end, I renounce exploring the mystery of the historical personality of Muḥammad.” Nöldeke is best known for his reordering of the 114 Sūrahs of the Qurʾān to match what he considered to be their true historical occurrence. Nöldeke based this work on the sequence of revelation with the development of content and the origination of new linguistic styles. The Nöldeke Chronology divides the Sūrahs of the Qurʾān are into four groupings: the First Meccan Period, the Second Meccan Period, the Third Meccan Period, the Medinese Period. Nöldeke considered this arrangement to be more coherent and comprehensive. Despite this attempt made by Noldëke, and later on by Schwally, Blachère, etc., Brother Bruno believes that there is no reason to give the “Sūrahs” an order different from the one found in the accepted “vulgate.”

Carl Heinrich Becker (1876-1933) was a German orientalist and politician. He was one of the Wilhelmine period’s most eminent orientalists and is considered a co-founder of modern and contemporary Oriental studies in Germany. He was at the same time an important reformer of academics in the Weimar Republic. In 1921 and from 1925 to 1930, he was Prussian Minister of Education.

Carl Heinrich Becker (1876-1933) was a German orientalist and politician. He was one of the Wilhelmine period’s most eminent orientalists and is considered a co-founder of modern and contemporary Oriental studies in Germany. He was at the same time an important reformer of academics in the Weimar Republic. In 1921 and from 1925 to 1930, he was Prussian Minister of Education.

His comparative analysis of Christianity and Islam, entitled Christentum und Islam (1907), represents the first major work of modern oriental studies. For Becker, Christianity and Islam present a complex parallel historical development, being religious systems that are fundamentally similar, which only diverge at the point of the Renaissance. Becker was introduced to oriental studies through Old Testament criticism, the field’s traditional point of entry. He quickly adopted the modern Orient as his object of study. In 1908, Becker accepted an appointment at the Kolonialinstitut in Hamburg, an important training ground for Germany’s colonial and overseas administrators. While in Hamburg, Becker aggressively advocated the implementation of Islamwissenschaft (the scientific study of Islam) on behalf of Germany’s colonial project. Becker’s first publication at Hamburg, Islam and the Colonisation of Africa (1910), a none- too-subtle treatise on racial and religious hierarchies in Africa, exemplified his deep commitment to Islamwissenschaft. Becker had a tendency to adapt his writings for use by the colonial establishment that he served. The publication of Christianity and Islam represents a liminal moment in Becker’s academic career when was no longer a traditional orientalist but not yet a crude mouthpiece for German colonial ambitions.

Michael Jan de Goeje (1836-1909) was a German-speaking Dutch Orientalist, (1836-1909) From 1854 to 1858, Goeje studied theology and Oriental languages at the University of Leiden, and became particularly proficient in Arabic. After taking his Doctorate of Letters there in 1860, he did postdoctoral studies at the University of Oxford, where he collated the Bodleian Library manuscripts of the important medieval Arabic geographer Al-Idrīsī. In 1883, he became a professor of Arabic at Leiden until his retirement in 1906.

Michael Jan de Goeje (1836-1909) was a German-speaking Dutch Orientalist, (1836-1909) From 1854 to 1858, Goeje studied theology and Oriental languages at the University of Leiden, and became particularly proficient in Arabic. After taking his Doctorate of Letters there in 1860, he did postdoctoral studies at the University of Oxford, where he collated the Bodleian Library manuscripts of the important medieval Arabic geographer Al-Idrīsī. In 1883, he became a professor of Arabic at Leiden until his retirement in 1906.

Goeje exerted great influence not only on his students, but also on the theologians and eastern administrators who attended his lectures. In 1886, he became Foreign correspondent of the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres. He headed the International Congress of Orientalists in Algiers in 1905. He was a member of the Institut de France, was awarded the German Order of Merit, and received an honorary doctorate from Cambridge University. At the time of his death, he was President of the newly formed International Association of Academies of Science. He became a member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1869.

During his career, Goeje edited many Arabic works, the most important of which was the 13-volume medieval history Annals of Tabari (1879–1901). He was also chief editor of the first three volumes of the Encyclopaedia of Islam (1908). His numerous editions of Arabic texts are still of great value to scholars today.

Martin Lings, Muḥammad, his life based on the earliest sources, London, 1983; translated from English by Jean-Louis Michon: Le Prophète Muḥammad. Sa vie d'après les sources les plus anciennes, Seuil, 1986, p. 28.

_______________ Martin Lings (1909-2005) was a British religious scholar, museum keeper, and author. Lings was an authority on Sufism and Islamic culture. Raised in a Protestant family, he abandoned his religious beliefs as a young man. He attended Magdalen College, Oxford, where he earned a Bachelor of Arts in English in 1932. While lecturing in Anglo-Saxon and Middle English at the University of Kaunas in Lithuania for four years, he earned a Master of Arts in 1937. In 1939, Lings travelled to Cairo, Egypt, to visit a friend then working as an assistant to philosopher René Guénon, whose work sparked Lings’ curiosity. Lings became Guénon’s new assistant, and of necessity he learned to speak Arabic. Converting to Islam, he adopted the Islamic name of Abu Bakr Siraj ad-Din and took a job as a lecturer in Shakespeare at the University of Cairo in 1940, remaining there until 1952, when riots against the British compelled him to return to England. Having become interested in Arabic culture, he matriculated at the University of London to earn a bachelor’s degree in Arabic in 1954 and a doctorate in 1959. While at the university, Lings became a disciple of metaphysical philosopher Frithjof Schuon, who taught him about Sufi doctrine and methods. His doctoral thesis was later published as the biography A Moslem Saint of the Twentieth Century: Shaikh Ahmad al-Alawi (1961). Lings then embarked on a second career as a writer and keeper of museum book and manuscript collections, specialising in Arabic and Oriental works. From 1955 to 1974 he was an assistant keeper, then keeper, of Oriental manuscripts and printed books at the British Museum. Meanwhile, he produced such books as a comprehensive volume on Sufi doctrine (The Book of Certainty), an introduction to Sufism entitled What is Sufism? (1975), and a definitive biography Muḥammad, his life based on the earliest sources.