THE ALGERIAN WAR

1. A ROMAN LAND, A CHRISTIAN LAND

FROM the first days of the conquest, French Algeria took over from Roman Algeria. Everyone – colonists, soldiers, priests, archaeologists, academics from our colonial period – were conscious of reconnecting with Rome which, during six hundred years, ense et aratro, “ by the sword and the plough ”, had pacified and colonised Africa.

IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE LEGIONS

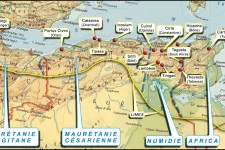

Facing south, the Romans had established a series of fortifications, the “ limes ”, in order to prevent nomadic tribes from coming to sterilise lands capable of growing crops, by driving their herds over them. Behind the “ limes ”, peace and security were assured by a few thousand legionaries, joined by Berber auxiliaries. Cities increased in number, which prepared a favourable ground for the expansion of Christianity, when the Empire was converted. The main wealth of the African provinces was agriculture. Not only did it feed their own population, but it also supplied Rome with wheat, wine and olive oil. Communications were maintained by 20,000 km of roads that encouraged interior commerce. Morocco was linked to the Tripolitan region by a coastal road, while another road, as strategic as it was commercial, ran alongside the limes.

Roman colonisation was an undeniable success; imposing ruins attest today that it turned Africa into a Roman land.

General Vanuxem, who was in command in the Aures district in 1955, testifies: « Rome is everywhere. It is still Roman canalisations that provide water to French farms. A road from Batna goes to Lambaesis, probably the richest archaeological site that exists, where the camp of the IIIrd Augusta was located; one can climb the verdant embankment at Arris, then descend by a red road to Tighanimine, where the legionaries of the conquest and those of today are astonished by a gap in the cliff through which the road and canal pass. It was pierced in the rock by the Roman Legion which, like ours, engraved its exploits on the rock. »

A CHRISTENDOM OF MARTYRS AND DOCTORS

Something of which we are not sufficiently aware is that ancient Africa was deeply Christian, perhaps the most Christian land of the whole Empire. Persecutions there had been so violent that St. Augustine was able to say: « The ground of Africa is replete with the bodies of holy martyrs. » Such as those of St. Felicitas and St. Perpetua, martyred in 203 at Carthage (Tunis), during the reign of Septimius Severus, torn in the arena by a furious cow, and finished off by the sword. « Sanguis martyrum semen christianorum » Tertullian, their contemporary, said – a formula that St. Cyprian, Bishop of Carthage and doctor of the Church, signed with his blood before his people in 258.

Something of which we are not sufficiently aware is that ancient Africa was deeply Christian, perhaps the most Christian land of the whole Empire. Persecutions there had been so violent that St. Augustine was able to say: « The ground of Africa is replete with the bodies of holy martyrs. » Such as those of St. Felicitas and St. Perpetua, martyred in 203 at Carthage (Tunis), during the reign of Septimius Severus, torn in the arena by a furious cow, and finished off by the sword. « Sanguis martyrum semen christianorum » Tertullian, their contemporary, said – a formula that St. Cyprian, Bishop of Carthage and doctor of the Church, signed with his blood before his people in 258.

The same Cyprian said: « No one has God for his Father who has not the Church for his mother. » The Church of Africa, daughter of the Roman Church, is not our mother, but our sister in the Faith, and we came in 1830 to inherit the legacy that had escheated for twelve centuries: the legacy of the martyrs and the doctors of the Church such as Tertullien, St. Cyprian and St. Augustine, the latter considered as the Father of the Western Church.

DURING THE CENTURY OF THE VANDALS

At the beginning of the fifth century, the Roman Empire, the victim of its decadence, collapsed under the blows of the barbarian invasions. Africa was not spared. The Vandal hoards, led by their king, Genseric, swept through Roman Africa and St. Augustine helplessly witnessed the ruin of all that he loved. In hope, however, he was able to outline the plans of the future City of God, as Georges de Nantes would do in 1962!

For the abandonment of African Christianity on the eve of the Second Vatican Council marked a defeat for the Church and a decline of civilisation, similar in every respect to the collapse of Roman Africa under the blows of the Vandals. « I consider the miserable column of those 4900 priests whom the son of Genseric sent to the Moors in 454 to be an eternal warning. Three years after the liberating resistance of Gaul and Rome to the invasion of the Huns, they are the last image that the peoples who tottered under the barbarian thrust leave in History. They all died, killed or lost in the desert; they were the African priesthood », the young Fr. de Nantes had already written in Aspects de la France (How Éurope was saved, January 12, 1951).

Carthage was captured by the Vandals in 439. A Germanic people, the Vandals were Arian heretics. Their fury against the Catholic clergy and its churches did not, however, get the better of the vitality of Christianity. The number of 348 Catholic bishops given in a document from 480 (dioceses of that time were the equivalent of our large parishes) is confirmed by the rather brilliant image revealed by modern archaeology.

THE CATHOLIC RENAISSANCE IN THE CENTURY OF BYZANTIUM

The Catholic emperor Justinian decided in 533 to reconquer the provinces lost a century earlier. The Vandals, weakened by the comfort of the Roman villas in which they had settled, collapsed in four months before the Byzantine armies.

For Christian Africa, « the Byzantine era was the most sumptuous of all Antiquity » (Le Monde de la Bible, no 132, p. 50). The quasi totality of the population was then Christian, including the Berber tribes who were integrated into the provinces.

A THOUSAND YEARS OF SLAVERY UNDER THE YOKE OF ISLAM

African Christianity thus had resisted all invasions and political turmoil, but it would be annihilated by Islam. The underlying reason for the triumph, apparently so easy, of the Crescent over the Cross remains an enigma for historians.

It all began with two devastating Arab razzias in 647 and 665. Then a lasting occupation began in 670 with the founding of Kairouan, in present-day Tunisia. After several attempts made without great conviction by the Byzantines to recover their power, the Arabs captured Carthage the Great in 698.

Let us note, however, that « Carthage did not fall until 698 and that Ceuta (at the furthest point of Morocco in the Strait of Gibraltar) was not reached until 709. This slow progress of the conquest contradicts the too often repeated affirmation of a sudden collapse of Africa before the Muslims » (Le Monde de la Bible, no 132, p. 51) – an affirmation conveyed by the Muslim legends of the cavalcade of the horsemen of Allah.

From the eighth century, once the whole of Roman Africa was subjugated, silence fell over this suffering Christian community. Three centuries later, after the Hilalian invasion, there were only two African bishops left. Africa then entered into the darkness of slavery, which extended as far as Spain by means of the invasion of the Moors, who had come from present-day Morocco, pushed on by the Arabs, and even as far as Poitiers where Charles Martel brought them to a halt.

Islam imposed its domination by the sabre: « Christians who did not want to embrace Islam were massacred and their churches converted into mosques or burned down. The lives of women and children were spared, but eighty thousand were taken into captivity in Egypt. » (Canon Tournier, op. cit, p. 4)

The disappearance of Christianity was not, however, immediate. We have proof of the presence of Christians by their epitaphs in Latin from the tenth or eleventh century. Ten centuries of Muslim domination, however, would transform this civilised region into a devastated land. Even nature suffered. Against a background of rivalry between Arabs and Berbers, the different dynasties of caliphs, sultans and other tyrants who succeeded one another had nothing but savagery in common and knew only how to reduce populations to a misery on which Islam fed.

France did not wait until 1830 to want to deliver them. The first attempts go back as far as the thirteenth century. The initiative lay with the Blessed Virgin, who had two strings to her bow, in a manner of speaking: the redeeming of captives and the Crusade.

THE REDEEMING OF CAPTIVES…

In the twelfth century, Felix of Valois, of royal blood, founded with St. John of Matha the Order of the Holy Trinity, devoted to the temporal and eternal salvation of Christians who were prisoners of the infidels. Both of them were favoured by visions.

In this thirteenth century that marked the height of Western Christianity, the Moors dominated all of North Africa, from Egypt to Morocco, and occupied half of Spain. Pirates crisscrossed the Mediterranean, attacked merchant ships or small fishing boats, debarked on poorly defended islands or the coasts of Spain, France or Italy, pillaged and burned villages and captured the inhabitants in order to reduce them to slavery. Those who denied Jesus Christ were immediately showered with honours. Nothing, however, was spared those who refused to renounce the Faith: forced to do the hardest labour, many died of the plague or typhus, or succumbed to ill treatment.

Thus Barbary, as it was called at that time, was for our Christian countries a permanent stimulus, giving rise to heroic marvels of charity under Heaven’s inspiration, in order to come to the help of souls in danger of apostasy if « no one prays and makes sacrifices for them ». This was already a well-understood truth and a nagging concern.

Nevertheless the Blessed Virgin, who wanted to mobilise the whole of Christendom, did not merely content Herself with one Order, She created a second one devoted to the redeeming of captives. On August 1, 1218, She appeared to St. Peter Nolasco, the tutor of king James I of Aragon.

Nevertheless the Blessed Virgin, who wanted to mobilise the whole of Christendom, did not merely content Herself with one Order, She created a second one devoted to the redeeming of captives. On August 1, 1218, She appeared to St. Peter Nolasco, the tutor of king James I of Aragon.

Assisted by Raymond of Peñafort and James, king of Aragon, Peter Nolasco thus established the religious and military Order of Our Lady of Mercy. Military, because the brother knights, even priests, wore the sword and knew how to use it! They added to the three ordinary vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, a forth, heroic one: that of remaining captive in the power of the infidels if that proved to be necessary for the redemption of their unfortunate Christian brothers who had fallen into slavery.

In that time, a Moorish prince from Andalusia, whose name was Moulay Abdallah, a doctor by profession, a learned astrologer, converted by St. Peter Nolasco, requested baptism and received the habit of the Order of Mercedarians, with the name of Brother Paul.

… BUT ALSO THE CRUSADE

King St. Louis was also preoccupied with the situation of the Franks of the Holy Land. After having led the seventh Crusade in 1249, sojourned in the Holy Land, and given to the French Levant a fifty year respite thanks to the wise measures taken, he nonetheless considered himself obliged to participate permanently in its defence – a concern that the sons of St. Louis would never forget from Philip the Fair to Charles X.

In July 1270, the armada of Crusaders mustered by St. Louis came together before Cagliari, Sardinia, and driven by a favourable wind they made for Tunis, which they reached in two days. Why Tunisia?

From a strategic viewpoint alone, it was inspired: « As a prelude to an offensive directed against the sultan of Egypt, Jean Richard explains, the descent into Tunisia, if it succeeded, would have allowed the Crusade to be reinforced, resupplied, and better financed, before tackling its main adversary. All the more so because at that time, Tunisia was providing assistance and supplies to the sultan of Egypt in his fight against the Latins. To occupy it would deprive the Egyptians of this help… Tunis did not make him forget Cairo. » The historian of St. Louis adds :

« Nevertheless, this diversion was not necessary unless some pressing reason made a descent to Tunisia desirable. The only reason cited by historians is of a missionary rather than a strategic character: it was a question of converting the emir Mohammad to Christianity. » (Jean Richard, St. Louis, Fayard, 1983, p. 563)

The crusader King had charged the ambassadors of Emir Mohammad with transmitting this message: « Tell your master that I desire so much the salvation of his soul that I am willing to spend the rest of my days in the prisons of the Saracens, in order for your king and his people to become genuinely Christian. »

He would do even better by offering himself as a victim. Afflicted by the typhus epidemic that had struck the army, the king had the Cross placed « in front of his bed and before his eyes… and each time that he had it brought to him he kissed it with great devotion and embraced it with great reverence ».

He gave up his soul at the very hour when the Son of God died for the salvation of the world on Monday, August 25, 1270. The holy King, who had never dissociated the mission from the Crusade, had just conquered the heavenly Jerusalem. By gaining a foothold in the Maghreb, he had also acquired the assurance of the evangelising and colonising mission of France, handing down to us as a right, a privilege and a duty towards this land and its peoples for their eternal and temporal salvation.

The future will show us that « all human history is sacred, for it is conducted by Providence from a perspective so farsighted and immense that it surpasses the human mind completely. The Catholic Faith, however, is in no way shaken by the slowness at which the plan for universal redemption at work in the world proceeds […]. When God wills, He will restore to Christ His Son, Our Lord, His former Kingdom and He will extend it to the ends of the earth, more beautiful than ever, a holy Kingdom, the heavenly Jerusalem. »

THE SPANISH RECONQUEST

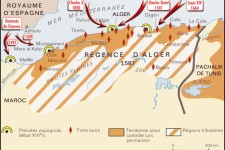

In Spain, the time of the Reconquest had come. It had already begun long ago, actively encouraged by Frankish knights. Due to divisions between the Christian princes, however, it was necessary to wait until January 4, 1492, to see Ferdinand the Catholic and Queen Isabel, his spouse, bring to a successful end the reconquest of Spanish lands from the Saracens by the capture of Granada, the capital of the last Muslim kingdom on the peninsula. In order to prevent a possible return of the Moors Spain, under the holy instigation of the Archbishop of Toledo and the king’s Prime Minister, Jimenez de Cisneros, understood that she would have to continue the Crusade into Barbary.

The bishop had himself appointed general-in-chief and embarked with his army in March 1509 bound for Mers-el-Kebir. The debarkation took place without difficulty.

A well-led battle took Moors and Arabs by surprise and opened the city of Oran to the victors.

Soon afterwards, Bougie fell in turn. These two successes obtained with lightening speed had a great impact throughout Christendom and on local sovereigns. The latter hastened to submit to the Spanish, who considerably extended their domain. Everything gave hope of a definitive occupation of the Barbary Coast by Spain, when suddenly it was learned that this magnificent movement had been stopped. Isabel the Catholic had passed away; Ferdinand let himself be absorbed by European politics, and his people turned their gaze towards America…

Seeing the hesitation of the Spanish, Algiers took advantage of it to raise the standard of revolt against them, calling for help to two pirates, the Barbarossa brothers. There followed a dark period that lasted until the French conquest, that is, three centuries of piracy that fed on the flesh and blood of Christian slaves. “ Privateering ” and the profession of “ corsair ” became an industry that enriched the treasury of the deys and brought to the population manpower, profit and pleasure.

These profits did not lessen the religious fanaticism of the holy war preached by the Turks. Hence the immense scandal of which Francis I was guilty when he entered into an alliance with Suleiman the Magnificent, sultan of Constantinople, sovereign of the Ottoman Empire, against Charles V, at the risk of causing the collapse of the whole of Christendom.

CHARLES V’S FAILURE

In July 1535, twenty years after the end of Jimenez’s Crusade, Charles V succeeded in recapturing Tunis from the Barbarossa brothers and decided in 1541 to crush the pirates’ den that Algiers had become. He organised a formidable armada: 65 galleys and 451 transport ships, which were commanded by one of the most illustrious admirals of his time, Andrea Doria, with more than 12,000 sailors and an expeditionary corps of 22,000 men which, by its international composition, prefigured the modern intervention forces of the UN, says an author who does not know how right he is! as what follows will show.

In July 1535, twenty years after the end of Jimenez’s Crusade, Charles V succeeded in recapturing Tunis from the Barbarossa brothers and decided in 1541 to crush the pirates’ den that Algiers had become. He organised a formidable armada: 65 galleys and 451 transport ships, which were commanded by one of the most illustrious admirals of his time, Andrea Doria, with more than 12,000 sailors and an expeditionary corps of 22,000 men which, by its international composition, prefigured the modern intervention forces of the UN, says an author who does not know how right he is! as what follows will show.

The bringing together of this enormous operation took time. Delays accumulated. The armada was only ready in October. It was late in the season, especially for the galleys, which normally do not navigate after the equinox. Heeding neither the warnings of Andrea Doria, nor the fears of the Pope, Charles V cast off; the galleys debarked the troops to the west of Algiers on October 23. The following day, after having decimated by canon a great part of the dey Hassan Agha’s army, the emperor installed his headquarters on a hill, eight hundred metres south of the Casbah. Success seemed certain.

In the evening, however, a storm of incredible violence broke out, which flooded and ravaged the Christian camp. Torrents of rain swallowed up powder, arms and supplies. At daybreak, in a thick fog, the Turks attacked. The wet muskets of the imperial troops were unusable. At the head of the German contingent Charles V valiantly withstood the assault, but at noon, when the fog had lifted, the battle was lost.

At sea, the disaster was even worse. There was not the slightest shelter for the ships and their crews. The vessels were torn from their anchors, went drifting off, collided and sank, ramming into one another. The storm sank or broke on the beach more than a hundred and fifty ships; the others had to set sail and flee. Charles V abandoned weapons and baggage and marched towards Cape Matifou to re-embark, having lost half of his forces and a third of his fleet!

On the way back, Charles V again ran the risk of being shipwrecked off Cartagena. After a retreat in a monastery, he publicly recognised his error: « It is not a question of getting up early in the morning, but of getting up at the appropriate hour, and this hour is in the hand of God. » (Pierre Serval, Algers fut à Lui, Calman-Lévy, 1965, p. 14)

In the meanwhile, the Turkish power gained a reputation for invincibility from this success over the greatest Christian princes of the time. Lepanto would put an end to this later, in 1571. Yet in North Africa, the Regency of Algiers, vassal of the Ottoman Empire, would continue to infest the Mediterranean with its corsairs, living on plunder, reducing Christians to slavery, for three hundred years.

IN THE SERVICE OF THE ETERNAL KING

On August 15, 1534, the year before Charles V’s expedition, St. Ignatius and his first companions made their vow at Montmartre to place themselves at the disposition of the Sovereign Pontiff for the conversion of the infidels. In 1540, Pope Paul III officially approved the constitutions of the Company of Jesus, where it was specified that the religious of this Company could be sent, by order to the Pope, to any infidel country, especially to the Muslims, which at that time were designated by the generic name of Turks.

Thus, we are not surprised to see Ignatius follow with interest the operations of the army of Charles V against the African Moors and even to draw up for the emperor in 1544, a project for an expedition against the Turks.

During the last years of his life, St. Ignatius dreamed of going to Africa « to use the days that he had left to live for the evangelisation of the lands of Barbary. » It is said, though, that Muslims cannot be converted! The conversion of a prince from the Moroccan city of Fez, who became a religious under the name of Balthazar Loyola Mendez, refutes such an assertion.

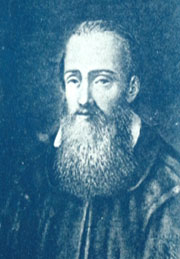

THE CONVERSION OF THE SULTAN’S SON

The event took place in 1655 and its hero was Moulay-Mohamed-el-abbas, heir of the sultan of Fez. Wanting to fulfil his pilgrimage to Mecca this young man, full of promise, went first to Tunis where he embarked on an English vessel bound for Egypt. As the English ship was inspected by the fleet of the Knights of Malta, the prince was made prisoner with his retinue and taken to Malta, where eight months of captivity, of contacts with Christians and signs from God convinced him of the falseness of the religion of Mahomet. He declared one day that he wanted to become Christian. He was baptised on July 31, 1656, taking for godfather the commander of the Order of Malta, Balthazar Mendez, whose name he received, and adding to it that of Loyola, in honour of the founder of the Company of Jesus whose feast was celebrated on that day.

At first he considered withdrawing into a desert in order to live there the penitent life of the solitaries, but thinking that exercising the apostolate towards his former co-religionists would be more agreeable to God, he resolved to study the sacred sciences and went to Rome, where he hastened to request admission into the Company of Jesus. When his formation was completed, he was charged with the evangelisation of the Muslims detained in penal servitude in Genoa and Naples, and on the vessels of the main ports of the peninsula. He carried it out with such zeal and devotion that he converted more than 1500 in the space of a few months! founding in each city a confraternity destined to help the new converts. He also found the time to publish a book refuting the doctrine of the Koran.

In 1667, he obtained from his superiors what he had desired for a long while: to go to the Great Mongol, the Muslim sovereign of the Indies, in order to convert him at the risk of his life. Providence, however, decided otherwise: he died even before embarking at Lisbon. « God contented Himself, wrote his first biographer, a, witness to his death, with the desire that he had for the conversion of these peoples and for the martyrdom that he desired with such ardour. »

MORE THAN A MILLION SLAVES

The regencies of the Barbary Coast continued to be, on the testimony of those who had been imprisoned there, « the scourge of Christendom, the terror of Europe, the height of cruelty in all its forms and the refuge of impiety ».

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Algiers had crammed 36,000 Christians (out of 180,000 inhabitants) into its convict prisons. « Between 1530 and 1780, almost certainly a million and very probably as many as 1,250,000 white, Christian Europeans were enslaved by the Muslims of the Barbary Coast […]. The estimates that we have reached show that, for the larger part of the first two centuries of the modern era, there were almost as many Europeans forcibly abducted to the Barbary Coast to work there or to be sold as slaves, as there were West Africans embarked to slave away on the American plantations. » (Robert C. Davis, Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters, White slavery in the Mediterranean, 1500-1800, Éditions Jacqueline Chambon, April 2006)

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Algiers had crammed 36,000 Christians (out of 180,000 inhabitants) into its convict prisons. « Between 1530 and 1780, almost certainly a million and very probably as many as 1,250,000 white, Christian Europeans were enslaved by the Muslims of the Barbary Coast […]. The estimates that we have reached show that, for the larger part of the first two centuries of the modern era, there were almost as many Europeans forcibly abducted to the Barbary Coast to work there or to be sold as slaves, as there were West Africans embarked to slave away on the American plantations. » (Robert C. Davis, Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters, White slavery in the Mediterranean, 1500-1800, Éditions Jacqueline Chambon, April 2006)

These slaves led a life of misery. The women were destined for harems and the men for convict prisons, servile work in the clutches of unscrupulous owners, or galley slaves.

How could they be got out of there?

After a period of decadence, the Trinitarians and the Mercedarians experienced a new impetus in the seventeenth century, through the momentum of the Counter-Reformation

Diplomatic treaties were signed to limit the effects of privateering, but their implementation compelled the English, French, Dutch and Spanish powers to make military demonstrations and pay heavy tribute to insure a very relative liberty for their vessels. The deys at that time signed all that was asked of them and respected no commitment.

SAINT VINCENT DE PAUL OR CHARITY IN ALL ITS FORMS

At last, in the seventeenth century there emerged a great plan, which is that of the Sacred Heart. St. Vincent de Paul, chaplain of the galleys and founder of the Congregation of Priests of the Mission, better known as the Vincentians, had himself been a slave of the Turks for two years in Tunis. He founded in 1640, with the help if the Duchess of Aiguillon, the “ Work of the Slaves ”, in order to « spiritually and corporally assist [the slaves] by visits, alms, instruction and administration of the Sacraments ». This program was to be the hub for the funds sent for the redeeming of captives.

At last, in the seventeenth century there emerged a great plan, which is that of the Sacred Heart. St. Vincent de Paul, chaplain of the galleys and founder of the Congregation of Priests of the Mission, better known as the Vincentians, had himself been a slave of the Turks for two years in Tunis. He founded in 1640, with the help if the Duchess of Aiguillon, the “ Work of the Slaves ”, in order to « spiritually and corporally assist [the slaves] by visits, alms, instruction and administration of the Sacraments ». This program was to be the hub for the funds sent for the redeeming of captives.

« Pierre Dan estimates that between 1605 and 1634 the inhabitants of Algiers captured more than 600 ships, worth more than twenty million pounds; the 80 French merchant ships that they captured between 1628 and 1635 were valued at 4,755,000 pounds; likewise, the redeeming of 1006 slaves at Algiers in 1768 cost the French Trinitarians 3,500,000 pounds. » (R. C. Davis, op. cit., p. 58)

This redeeming, however, by confirming the market value of the slaves, encouraged piracy, like modern hostage-taking: to pay ransom is to foster its development. This is why St. Vincent de Paul advocated military intervention: « It would appear that if we took on these people, we would get the better of them », he wrote. He could not have said better.

St. Vincent de Paul devised, with one of the most famous French sailors of his time, the knight Paul, admiral of the king’s fleet, greatly feared by the Berbers, the project of attacking Algiers to deliver the slaves.

Two years before his death, this good Monsieur Vincent preached war as a holy work! His wish to see the success of a military expedition against the Barbary states remained with him to his last days. He would die without seeing its realisation, but let us observe now that the expedition of 1830 owed its success to St. Vincent de Paul, under whose patronage King Charles X placed it.

THE GREAT PLAN OF THE SACRED HEART: Louis XIV AND ALGERIA

The Treaty of the Pyrenees that was signed on September 7, 1659 put a temporary end to European wars and once again gave France great freedom of action.

Louis XIV then conceived the project of landing an expeditionary corps at a point on the Algerian coast.

The French plan was to capture a smaller and less well defended port in order to fortify it and turn it into a permanent naval base against the the Barbary powers… On Tuesday, July 22, 1664, a French squadron approached the small city of Djigeri, half way between Algiers and Bone, today the port of Jijel (see the map). An expeditionary corps landed there, six thousand strong, composed of the best troops of the kingdom, under the command of the Duke of Beaufort. Alas! After three months of fierce combat, it was a failure. Dissentions between the Duke of Beaufort, head of the expedition who proved himself incapable, and his generals and admirals, made the organisation of the beachhead impossible.

Above all, however, Colbert’s mercantile spirit prevailed over the spirit of the Crusade preached by Bossuet. Guaranteeing freedom of navigation in the Mediterranean in order to develop commerce in the Levant, with the Barbary Coast included, was preferred to extending the Kingdom of Christ, to the great despair of missionaries posted in Africa.

JEAN LE VACHER

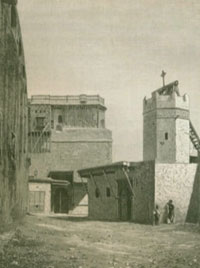

Fr. Le Vacher, one of the first sons of St. Vincent, had first been named Apostolic Vicar of Tunis where he exercised his zeal among the slaves under cover of his functions as consul. In 1666, in addition to this charge, he was appointed Apostolic Vicar of Algiers. It was a curious parish! Tunis, compared to this pirates’ den, was a sinecure. Nevertheless, he displayed extraordinary zeal at the task: « If on the one hand, he wrote to his superior, I saw the road to Heaven open, with the permission to go there, and that of Algiers, I would take rather take this latter. » Honoured with the confidence of the King and the Pope, the “ Consul for the French nation ” went through the slave market in order to comfort the newly arrived, and to redeem the most vulnerable.

The Muslims had the habit of throwing old slaves out on the streets to get rid of useless mouths. He obtained permission to open a hospital to take them in. He then worked hard at organising religious practice among the slaves. By pointing out that a well-treated slave was more profitable than an ill-treated slave, he succeeded in winning over the authorities. All this at the risk of his life, for the anger of the dey could explode at any time, especially when he was bombarded by French ships!

After the war with Holland, Louis XIV resolved to return to the strong-arm methods of the beginning of his reign. Duquesne, at the head of a fleet of eleven ships and five small bomb galleys, came to blockade Algiers in August 1682. He partially destroyed it, but fearing the storms of September, he returned to Toulon without success. Louis XIV resumed the operation: Duquesne reappeared off Algiers the following year (1683) and bombarded it once again in reprisal, after the French commander of a defeated frigate had been sold as a slave. This time, however, it cost the life of the “ consul for the French nation ”.

Under pressure from the bombardments, negotiations began. Refusing the overtures of the dey, the intransigent Duquesne, who was a Protestant, thought it clever to release a hostage, a former corsair chief called Mezzomorto, a renegade. He had held out the possibility that, using his influence as a corsair, he would be able to eliminate and replace the dey, which would facilitate the negotiations. In fact, as soon as he disembarked, Mezzomorto stirred up the militias against the dey, stabbed him himself and had himself proclaimed dey in his stead. As was to be expected, however, Mezzomorto betrayed Duquesne and broke off negotiations with him. The bombardments therefore resumed. The renegade then took the French consul, Fr. Le Vacher, hostage. He was taking revenge for an old quarrel for, not long before, the French priest had forced him to abandon a beautiful young slave that he had destined for his harem.

« You made signals with flags from the terrace of the consulate to inform the French ships! You have betrayed us; you must die! »

The priest did not reply. The renegade continued:

« If you accept the turban, if you recognise Allah as God and honour his prophet, then I guarantee that I will spare your life!

– One cannot be saved by denying the Saviour, and you know it full well! »

Pale with rage, Messomorto had him attached to the muzzle of a seven-metre cannon that defended the entrance of the port and ordered that it be fired. It happened, however, that not a single Turk or Jew would consent to set fire to the fuse; a renegade was needed. The shot was fired and half of the body of the Apostolic Vicar was projected into the sea. From the place where it fell, a column of fire could be seen rising. It was on July 27, 1683.

Pale with rage, Messomorto had him attached to the muzzle of a seven-metre cannon that defended the entrance of the port and ordered that it be fired. It happened, however, that not a single Turk or Jew would consent to set fire to the fuse; a renegade was needed. The shot was fired and half of the body of the Apostolic Vicar was projected into the sea. From the place where it fell, a column of fire could be seen rising. It was on July 27, 1683.

A lack of munitions forced the French fleet to return to Toulon, once again without success. In 1685, Tourville resumed the destruction begun by Duquesne and obtained a second treaty, which became a dead letter the same year. In 1688, Admiral Destrées resumed this series of bombardments; in the short term, this led only to the execution of the consul of France, missionaries and Christians.

Nevertheless, Algiers, continually blockaded, fell into ruin. The Turks became weary; they sent an ambassador to Louis XIV and a treaty was concluded in 1690. Recalling the old alliance between France and Turkey, it provided for the restitution of slaves, the restoring of French establishments in Africa, mutual respect of merchant ships by the French and the Turks. This peace that was concluded for “ a hundred years ”, on his word as a dey… was not respected by the successive deys any more than the previous ones.

It remains humanly inexplicable that powerful Christendom had tolerated being thus abused for such a long period by a handful of pirates. One must not forget, however, that the Sacred Heart had a plan, revealed in 1689, with which Louis XIV wanted nothing to do. We know this by the revelations of Paray-le-Monial to St. Margaret Mary: « My Heart wants to triumph over his and, by his mediation, over those of the great ones of the world. » He declared Himself « true King of France » and, consequently equitable and beneficent, He asked Louis XIV that His Sacred Heart be engraved on his arms and painted on his standards. If he did this, divine promise! Louis would be victorious over all his enemies who were also THOSE OF THE CHURCH. This would certainly seem to include the pirates, who were enemies of both King and Church.

Alas! Louis XIV did nothing. So, a hundred years later, to the day, after the demand of the Sacred Heart, on June 17, 1789, the Third Estate transformed itself into a Constituent Assembly. It was the end of the most Christian monarchy.

THE CONQUEST OF ALGERIA

It was necessary to await the Restoration in order to see the great plan of the Sacred Heart reborn in the heart of the King of France. « The resounding reparation that I want to obtain by satisfying the honour of France will turn, with the assistance of the Almighty, to the benefit of Christendom », Charles X declared before the Chambers on March 2, 1830.

« TWENTY DAYS SUFFICED… »

On May 10, the army was ready. The thirty-seven thousand men of the expeditionary force embarked aboard the vessels gathered in the harbour of Toulon. The fleet, six hundred units strong, cast off on May 25, amidst the cheers of the population massed on the quays, and the music of the crews.

After a call at Palma de Mallorca, the squadron dropped anchor on June 13 in the Bay of Sidi Ferruch, a few kilometres west of Algiers. It was the feast of Corpus Christi. « What a coincidence! It struck me immediately, Amédée de Bourmont, one of the four sons of the commander-in-chief, wrote to his fiancée. Is this not a sign, a harbinger of resurrection for this old Christian land? » The landing took place without any opposition, and immediately a fortified camp was laid out on the peninsula of Sidi Ferruch.

The confrontation with the Muslims took place on June 19, on the edge of the Staouéli plateau. The howling and disorderly mass of their horsemen came to break up on our first lines without succeeding in dislocating them. Then it was the counter-attack. A witness related: « Never will I forget the enthusiasm and the ardour of our valiant troops. I can still see the soldiers climbing the heights of Staouéli at a run to shouts of “ Long live the King ”, brandishing their rifles at the end of which they had attached their handkerchiefs. » The victory was resounding. The next day, General de Bourmont had a Mass of thanksgiving celebrated on the front lines of the troops.

Then the progression resumed, under an oppressive heat, in a more and more difficult landscape. The enemy was everywhere, elusive, and causing heavy losses. Finally the French arrived in view of Fort Emperor, a formidable fort bristling with cannons that the Turks had built to the south of Algiers. The capture of the fort on July 4 tolled the knell of Hussein Dey, who capitulated the following day. The French army victoriously entered Algiers and Bourmont immediately had a large cross erected above the Casbah, as well as the white flag of the French monarchy. A Mass with Te Deum was celebrated there on July 6. The dispatch for this memorable day thus summarised the events:

Then the progression resumed, under an oppressive heat, in a more and more difficult landscape. The enemy was everywhere, elusive, and causing heavy losses. Finally the French arrived in view of Fort Emperor, a formidable fort bristling with cannons that the Turks had built to the south of Algiers. The capture of the fort on July 4 tolled the knell of Hussein Dey, who capitulated the following day. The French army victoriously entered Algiers and Bourmont immediately had a large cross erected above the Casbah, as well as the white flag of the French monarchy. A Mass with Te Deum was celebrated there on July 6. The dispatch for this memorable day thus summarised the events:

« Twenty days sufficed to destroy this State, the existence of which wearied Europe for three centuries. The gratitude of all civilised nations will be for the task force the most precious result of its victories. The glory that must be reflected on the French name will have largely compensated for the expenses of the war, but these same expenses will be paid by the conquest. »

In fact, the treasury of the dey totally covered the expenses of the expedition. Bourmont and his officers did not claim any part of it. Hussein and his janissaries were sent back to their country of origin. It was now a question of colonising and evangelising: « Perhaps, with time, General de Bourmont wrote in the conclusion of his report to Charles X, we will have the joy, by civilising the Arabs, of making them Christian. » For the first time in centuries, Christianity had resumed the offensive against Islam.

PROMISING BEGINNINGS

The population of Algeria at that time formed a rather disparate group: approximately three million inhabitants, divided into five different « nations » or races: the Turks, from Asia Minor; the Moors, the most civilised, the descendents of those who had been driven out of Spain; the Jews, very influential, despite the state of abjection to which they had been reduced; the Bedouins or nomads grouped into tribes on the plains of the interior; finally the proud Kabyles, of Berber race hidden away in their inaccessible mountains.

As the Muslim religion was the only bond that federated them, it was necessary, in order to affirm our sovereignty, to show that the Catholic religion had henceforth the right of the victor, hence the cross surmounting the Casbah. « If you ignore the will of God and the power of France, you will be held responsible for your country », Bourmont wrote to the lord Mustapha, the bey of Titteri. Nevertheless, it was also necessary to be careful not to clash head-on with the populations by removing overnight their religious and social framework – in Islam, both are connected – which had governed their lives for centuries. The lieutenant governor of the police of Aubignosc wrote, regarding the customs of the people from the Barbary Coast:

As the Muslim religion was the only bond that federated them, it was necessary, in order to affirm our sovereignty, to show that the Catholic religion had henceforth the right of the victor, hence the cross surmounting the Casbah. « If you ignore the will of God and the power of France, you will be held responsible for your country », Bourmont wrote to the lord Mustapha, the bey of Titteri. Nevertheless, it was also necessary to be careful not to clash head-on with the populations by removing overnight their religious and social framework – in Islam, both are connected – which had governed their lives for centuries. The lieutenant governor of the police of Aubignosc wrote, regarding the customs of the people from the Barbary Coast:

« We should consult them… but it would not in the least be proper to draw our principles from such customs. »

As much can be said of Article 5 of the capitulation, by virtue of which France committed itself to « allow free exercise of the Muslim religion ». In the mind of Bourmont and Charles X, this meant a simple tolerance granted to the Muslim religion, and not neutrality. France, a Christian power, could not be neutral. Muslims understood this perfectly. On the other hand, however, the King of France did not acknowledge the right of using the sabre, as the Muslims would have done, in order to force consciences to adhere to the true religion. It was up to the Church and her missionaries, happily concerted with the Christian power, to take over and conquer souls.

An army corps of auxiliary troops were immediately recruited from the Zouaoua, tribe, hence the name of “ zouave ”, the origin of our future African army. In accordance with the order of the King, the commander-in-chief wanted to extend the occupation of the territory as far as possible. He sent his son Louis to Oran, where the bey Hassan declared himself ready to recognise French sovereignty, while to the east, the port of Bougie and the citadel of Bone were occupied in the beginning of August 1830 by a detachment that had victoriously repelled the troops of the bey of Constantine.

The French plan did not stop there: entering into an alliance with the bey of Tunis, who was our friend, we could speak loud and firmly to the bey of Tripoli and force him through diplomatic means « never again to wage war on Christian powers and to reduce Christians to slavery no longer ».

Alas! At that very moment, in France, the miserable “ Three glorious ones ” once again overthrew the most Christian monarchy, and this « breaking of the alliance » called into question the colonising and missionary project of Charles X.