THE ALGERIAN WAR

7. THE GREAT BETRAYAL (1958-1961)

ON June 4, 1958, de Gaulle was triumphantly welcomed in Algiers. Standing in a convertible with General Salan on his left, he advanced under arches of flags between two lines of a progressively denser crowd that chanted, “ French Algeria ! ” and “ Long live de Gaulle ! ” Fr. Georges Schorüng, the Lazarist chaplain of the Mustapha Hospital, testified : « After May 13, an immense throng would have very willingly raised themselves to the dignity of Christians and at the same time to the dignity of becoming French. People asked me to baptise their children ! »

« I HAVE UNDERSTOOD YOU. »

Before speaking in public, de Gaulle confided to high-ranking civil servants : « I am going to speak to the crowd. I really do not want to make ill-considered promises. On no account will I lie to them. » This need to certify that he was not going to lie was surprising, troubling even ! At 7 p.m. from the forum balcony, “ the providential man ” shouted his famous « I have understood you ! » to the three hundred thousand people who were cheering him. In his Memoirs, he wrote : « I called out to the crowd these apparently spontaneous words as far as form goes, but they were in fact well calculated, for I wanted them to be enthusiastic about them without them carrying me further than I had determined to go. »

Before speaking in public, de Gaulle confided to high-ranking civil servants : « I am going to speak to the crowd. I really do not want to make ill-considered promises. On no account will I lie to them. » This need to certify that he was not going to lie was surprising, troubling even ! At 7 p.m. from the forum balcony, “ the providential man ” shouted his famous « I have understood you ! » to the three hundred thousand people who were cheering him. In his Memoirs, he wrote : « I called out to the crowd these apparently spontaneous words as far as form goes, but they were in fact well calculated, for I wanted them to be enthusiastic about them without them carrying me further than I had determined to go. »

The crowd answered with a tremendous ovation. De Gaulle went on : « I know what has happened here. I see what you have wanted to do. I see that the road that you have opened up in Algeria is the way of renewal and brotherhood. Well ! I note all of this in the name of France ! And I declare that from now on France will consider that there is everywhere in Algeria only one category of inhabitant; there are only fully-fledged French citizens with the same rights and the same duties. »

Nevertheless, his Marxist analysis grid led him to justify rebellion : « We must open the ways that were closed up until now to many people. This means that we must provide means of living to those who did not have them. This means that we must recognise the dignity of all those to whom we contested it. This means that we must secure a homeland for those who may have doubted that they have one. » What homeland was he talking about : France or Algerian Algeria ? Already ambiguity prevailed...

After speaking some words in praise of the French army’s valour, what did the head of state announce ? A programme of public security ? No, elections !

When de Gaulle called on both loyal and rebel the Algerians without discrimination to make a collective, democratic decision on the destiny of Algeria, he set in motion the very mechanism that led to deserting Algeria. « He was already making this people that was beside itself with joy acclaim the ideas that would lead them to their demise. As in classic drama, the same people cheered their saviour in the very forum where they would fall under the anti-riot police’s hail of bullets or would flee en masse this hell with their eyes red from weeping bitterly. » 1

When de Gaulle called on both loyal and rebel the Algerians without discrimination to make a collective, democratic decision on the destiny of Algeria, he set in motion the very mechanism that led to deserting Algeria. « He was already making this people that was beside itself with joy acclaim the ideas that would lead them to their demise. As in classic drama, the same people cheered their saviour in the very forum where they would fall under the anti-riot police’s hail of bullets or would flee en masse this hell with their eyes red from weeping bitterly. » 1

Fr. de Nantes denounced the other side of the betrayal : « No religious or moral authority of that time dared to denounce the imposture, the awful slandering hurled at a whole nation by its own born-defender, the promotion of killers to the rank of dispensers and legitimate defenders of the rightful aspirations of a people. No one since then has succeeded in re-establishing political and moral truth. Rebellion had already prevailed. » 2

Before leaving, de Gaulle confirmed General Salan in his double charge as general delegate and commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces in Algeria and gave him the following agenda :

« Order to land, naval and aerial forces of Algeria. During the three wonderful days that I spent in Algeria, I saw you under arms. I know the work that you accomplish under the orders of your leaders, that you do it with exemplary courage and discipline in order to keep Algeria for France and to keep it French. The population’s trust in the army, of which I had so many proofs, makes me sure that your efforts in the service of the country will be rewarded with a great national success. »

IN COMPLETE SUPPORT OF INDEPENDENCE

In order to obtain his nomination, on June 1, 1958 the head of government had reassured the Socialist deputies : « I alone can make the army toe the line because I am a general. May 13 was an act of illegality; I will never consider myself its heir. As for Algeria, I have a solution that the boldest among you would never dare consider. Here again, I alone can succeed. » 3 « From the first Cabinet Meeting, a member of his government indicated, it appeared that independence was where his thoughts were leading. » 4

De Gaulle did not believe in the spirit of May 13, in harmonious relations between the two communities, in fraternisation. On June 24, 1958, he declared to Alain de Sérigny, director of the Écho d’Alger : « It would be advisable to verify if these demonstrations, which are, of course, moving, really correspond to the deep feeling of the Muslim masses. » The journalist was shattered when he left the Hôtel Matignon (the official residence of the Prime Minister of France) : « Is it possible that I helped to hand over French Algeria to a man eager to ruin it, while believing that I was saving it ? »

De Gaulle used cunning from the day he came to power. « If I had said in June 1958, he confided later on to Jean Mauriac, that I wanted to give independence to Algeria, I would have been overthrown that very evening, and I would not have been able to do anything, but I always knew what I wanted to do. » 5

The words of General de Gaulle were sometimes contradictory, as it happens with opportunists and ambitious people who express themselves to fit the audience to whom they are speaking. Yet the guiding line of his thought did not change. On May 18, 1955, he explained to Louis Terrenoire, a former member of the Resistance and the son-in-law of Francisque Gay : « We are in the presence of a general movement in the world, of a wave that carries all peoples along toward emancipation. There are fools who do not want to understand... » And in 1956, to Christian Pineau, Minister of Foreign Affairs : « The only solution is called independence.

– Since you think so, General, say it publicly.

– The time has not come. »

On October 3, 1956, he confided to Moulay Hassan, the crown prince of Morocco : « Dear prince, your efforts for the independence of Algeria are laudable, but they will come to naught. A powerful, intelligent executive power would be necessary to lay down an Algerian policy with the required strength to impose it on its public opinion... This calls for revising the Constitution. » (Claude Paillat, La liquidation, Vol. 2, 1972, p. 385)

This was the program that he implemented as soon as he came to power in 1958.

HAS BETRAYED, IS BETRAYING, WILL BETRAY.

The man of the Appeal of June 18 6 still felt keenly resentful towards the French of Algeria, the great majority of whom had been supporters of Marshal Pétain. On November 25, 1960, he affirmed to Pierre Laffont, the deputy of Oran : « The cause of French Algeria is the revenge of “ Petainism ”. » 7

Furthermore, de Gaulle did not believe in the integration of the natives, and he did not consider raising them mentally and morally, even less converting them to Christianity. What interested him was to create Europe : « It is Europe, from the Atlantic as far as the Urals, he said, it is Europe as a whole that will determine the destiny of the world. » He was brought back to power by the great financiers in order to dismantle in the Empire what was being rebuilt in Europe : a great economic and technocratic whole. Yet, in his paranoia he hoped at the same time to acquire the leadership of the under-developed countries of the Third World. When he received Maurice Clavel in Colombey in 1956, he explained to him that he wanted « the independence of Algeria to inaugurate a policy of a world-wide challenge to United States and of rapprochement with the Third World ». Beginning in June 1958, he prepared his withdrawal from NATO by refusing the deployment of American missiles in France. His minister Alain Peyrefitte noted : « De Gaulle wants to put an end to the Algerian affair quickly in order to engage in grand global politics between the two blocs, a kind of politics that he alone can lead and that is the only one worthy of France. »

Furthermore, de Gaulle did not believe in the integration of the natives, and he did not consider raising them mentally and morally, even less converting them to Christianity. What interested him was to create Europe : « It is Europe, from the Atlantic as far as the Urals, he said, it is Europe as a whole that will determine the destiny of the world. » He was brought back to power by the great financiers in order to dismantle in the Empire what was being rebuilt in Europe : a great economic and technocratic whole. Yet, in his paranoia he hoped at the same time to acquire the leadership of the under-developed countries of the Third World. When he received Maurice Clavel in Colombey in 1956, he explained to him that he wanted « the independence of Algeria to inaugurate a policy of a world-wide challenge to United States and of rapprochement with the Third World ». Beginning in June 1958, he prepared his withdrawal from NATO by refusing the deployment of American missiles in France. His minister Alain Peyrefitte noted : « De Gaulle wants to put an end to the Algerian affair quickly in order to engage in grand global politics between the two blocs, a kind of politics that he alone can lead and that is the only one worthy of France. »

For the time being this policy served the Communist bloc : « Charles de Gaulle has the ability to make people believe that he is seeking the centrist position, a position that dominates everything, is free of any dishonest compromise, is materially as well as morally desirable, and is a guarantee of economic prosperity and an easy means to achieve peace, yet all the while he is knowingly taking us where we do not want to go, to Communism. He is the Catholic, military, aristocratic, and for the foreign countries, the French guarantor of this gigantic betrayal. He possesses for this task the calculating coldness and the two powers that the Gospel recognises as characteristic of the devil’s sons : the power of lying outrageously and of killing or crushing people once they have grasped his game clearly. I say it : it would have been better for us and, I fear, for this man that he was never born. » 8

A MASTERLY MACHIAVELLI

Peyrefitte had perfectly understood his master’s game : « He constantly has to manipulate to bring the soldiers, the pied-noirs in Algeria, and the conservatives in France to accept the unavoidable evolution, even if this means fooling them with decoys. » 9

The first decoy was the referendum of September 28, 1958 on the Constitution of the Fifth Republic. In Algeria, this vote was construed as a vote for or against French Algeria.

The FLN advocated abstention and multiplied threats and attempts on the lives of people who registered on electoral rolls : among others savageries were things like killing the offender within eight days or killing his wife or children. In spite of this pressure, 84 % of Algerians went to the polls and 96 % of them voted in favour. The assiduous participation of Muslims in this vote showed their will to be French citizens.

But eight days before the vote of September 28, the Management Committee of the FLN in Tunis marked its refusal of any compromise by proclaiming itself the “ Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic ” (GPRA).

On October 3, 1958, in a speech at Place de la Brèche in Constantine, General de Gaulle set out the broad outline of an economic development programme that would become the famous “ Plan of Constantine ”. This was the second de Gaullian decoy. In actual fact, he only took General Weygand’s projects from 1940-1941 out of their boxes : industrialisation, schooling, land redistribution, job creation, housing assistance... but without the political will to strengthen the colonial bond in the long term. Big capitalism, which would be able to survive after independence, would be the only beneficiary of this programme.

The third decoy : the restoration of the Republican State.

The populations of Algeria and Sahara sent seventy-one deputies to the Chamber, forty-eight of whom were Muslims. They took an oath to promote the integration of Algeria into France. What an illusion to believe this was possible in a democratic context !

« I AM ALGERIA ! »

General Salan began to become suspicious during General de Gaulle’s trip to Constantine in October 1958 : « I remember several of the general’s remarks : “ I obtained my referendum and my Constitution... I will be president of the Republic... I will have my bomb and power… ” We were no longer any use to him. He used us; he used Algeria. We no longer interested him ! What he wanted was to turn essentially toward his Europe; therefore, the war that was continuing here was embarrassing to him. There were so many contradictions in his attitude ! Was the general deceiving me while continually giving me, in word and in writing, tokens of encouragement and trust ? » 10 He was not mistaken.

General Salan began to become suspicious during General de Gaulle’s trip to Constantine in October 1958 : « I remember several of the general’s remarks : “ I obtained my referendum and my Constitution... I will be president of the Republic... I will have my bomb and power… ” We were no longer any use to him. He used us; he used Algeria. We no longer interested him ! What he wanted was to turn essentially toward his Europe; therefore, the war that was continuing here was embarrassing to him. There were so many contradictions in his attitude ! Was the general deceiving me while continually giving me, in word and in writing, tokens of encouragement and trust ? » 10 He was not mistaken.

In his press conference of October 23, 1958, the head of government put out a call in favour of a « peace of the brave », referring equally to rebel fighters within Algeria as to their leaders without. The FLN, which was in terminal decline, won undoubted prestige by it, and above all it understood that negotiation would be possible with de Gaulle.

Nevertheless, in this same speech, de Gaulle paid a glowing tribute to the army : « So many lives, so many homes, so many harvests to protect, that’s what the French army does indeed protect in Algeria ! What a hecatomb this country would experience if we were stupid and cowardly enough to abandon it ! » These are words that will judge him and his whole people with him.

De Gaulle multiplied transfers in order to enchain the army to his plan. General Miquel was forced to retire in June 1958 and Jouhaud was called back to France on October 15. De Gaulle offered Salan the post of ambassador... in the Pacific. He refused, of course, and received an honorary assignment as military governor of Paris in December 1958.

De Gaulle replaced him with two “ technicians ” who were if not Gaullist, at least legalistic and disciplined : Challe and Delouvrier. The former, Air Force General Maurice Challe, became commander-in-chief. This former resistance fighter did not come from the milieu of the African Army and had not directly participated in any colonial war or in the demonstrations of May 13. He was, however, a man who knew how to get on with people and was endowed with a fresh and ambitious mind; he had not concealed to his Parisian interlocutors that if he exercised the functions of commander-in-chief, he would know how to get resounding results quickly. As for the civil powers, they were assigned to Paul Delouvrier, a young European technocrat who was promoted to general delegate in Algeria. He received a single order from the head of government : « Never say : “ Long live French Algeria ! ” » 11

To journalists who were questioning the will of the head of state to keep Algeria French, Challe answered that if this was the case, he would never have agreed to succeed Salan. Concentrated on his determination to carry out his mission to annihilate the FLN, he was blind to the politics of the head of state, who was leading the army to his way of thinking for many months.

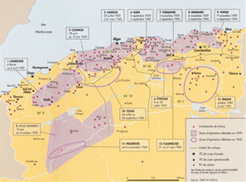

THE FIRST PHASE OF THE CHALLE PLAN

The district troops who covered the country were too scattered to eradicate the rebel bands, which sometimes counted more than a hundred men, and to eliminate from the population the subversive, military-political organisation (OPA) that was assuring their logistical support. The Challe plan, which was largely conceived and prepared by his predecessor, was going to compensate for this weakness. It was supposed to be implemented in two phases.

The first objective, to break up the rebel bands, was assigned to the elite units that constituted the « general reserves ». These troops formed a unit that was as unstoppable as a steamroller and were supported by airplanes and helicopters; their mission was to sweep through Algeria from west to east, from one border barricade to the other. The French army was finally taking the initiative again.

This phase started in February 1959.

THE PURSUIT COMMANDOS

After the manoeuvre of the elite troops, the second phase of the Challe plan was implemented : to create in every sector one or several « pursuit commando groups », light units living off the country and experienced in every kind of ruses and stratagems of anti-guerrilla warfare. Their mission was to pursue and finish off the bands decimated by the general units. Speed and secrecy prevailed over power. French officers commanded these commando units that were composed mostly of Muslims. They were familiar with the rebels, their itineraries, their refuges and their ways of fighting. They tracked them at night, guided by harkis.

SPECTACULAR RESULTS

The Challe plan was animated by the cheerful intelligence of the commander-in-chief and proved to be brilliantly efficient. The success of the initial operations exceeded expectations : 50 % of the rebel potential was destroyed in the area of Oran, 40 % in the area of Algiers, and just as much in the other regions. The ALN within Algeria was split up, broken.

In four wilayas out of six, the rebel OPA no longer existed; the rebels dug in their hiding places, hoping to make it through the cyclone unscathed. In the summer of 1959, there were officially no more than 13,000 moudjahidins in Algeria and 12,000 in Tunisia and Morocco. Actually, the latter only risked crossing our border barricade with « death behind them », that is to say under the threat of weapons. Many of them went over to the French camp. In 1959, they were two thousand; ten months later, their number had tripled, and they were among the most courageous and faithful harkis. In the Muslim population, more and more young people were joining our army. In 1960, there were 210,000 harkis, that is, eight times the number of rebels !

In four wilayas out of six, the rebel OPA no longer existed; the rebels dug in their hiding places, hoping to make it through the cyclone unscathed. In the summer of 1959, there were officially no more than 13,000 moudjahidins in Algeria and 12,000 in Tunisia and Morocco. Actually, the latter only risked crossing our border barricade with « death behind them », that is to say under the threat of weapons. Many of them went over to the French camp. In 1959, they were two thousand; ten months later, their number had tripled, and they were among the most courageous and faithful harkis. In the Muslim population, more and more young people were joining our army. In 1960, there were 210,000 harkis, that is, eight times the number of rebels !

At the same time as the French army tracked down the rebels, it was building roads, trails, military stations; the Muslims organised self-defence groups under the control ofsas officers to protect their villages. Schools, homes, and clinics were being opened; new sas units were created.

The French military victory was an accepted fact that no sincere person could contest. General de Gaulle publicly acknowledged it during the round of inspection, the “ mess tent tour ” that he made in Algeria from August 27 to 31, 1959. In Saida, de Gaulle declared : « As long as I live, the FLN flag will never fly over Algeria ! »

GUARANTOR FOR DE GAULLE’S POLITICS

« The fact that de Gaulle constantly came out in his favour convinced Challe that the FLN rebel chiefs were wrong to combine politics with operations, since on the basic points, the Elysée (official residence and office of the French president) sided with him and allowed him to obtain this military victory in which no one had ever believed. Thus Challe only thought about his plan. The rest did not count. » 12

Nevertheless, thousands of signs showed that de Gaulle was preparing the political victory of the FLN. When he became president of the Republic on January 8, 1959, he freed 7,000 prisoners and granted pardon to 180 rebels who were condemned to death, among whom was found Yacef Saadi, the terrorist from Algiers ! Ben Bella and his companions were transferred from the La Santé prison in Paris to the island of Aix, where their stay became more comfortable. Messali Hadj received authorisation to circulate freely in metropolitan France. These measures, far from disarming the terrorists, triggered new waves of attacks.

Yet, a new government decision of great impact should have opened the eyes of the commander-in-chief and his advisers.

SEPTEMBER 16, 1959 : SELF-DETERMINATION

Back in metropolitan France fifteen days after having fawned over the army and having exacted its obedience, the President of the Republic announced during a broadcasted speech : « The Algerians’ self-determination will finally decide of the fate of the country. » The Algerians would have to choose from among three solutions :

1° « Secession, in which some believe that they will find independence..., will lead to terrible misery, dreadful political chaos, general blood-letting and, soon, the bellicose dictatorship of the Communists.

« What can insurrection mean ? If its leaders are demanding the right to self-determination for Algerians, well ! all paths are open. » For the FLN, what a recognition this was of its demands ! In another speech, the head of state said that he was considering this secession « with a perfectly tranquil heart ».

2° « Becoming completely French », which would give the same rights to everyone, Europeans and Muslims. De Gaulle had advocated this solution one year earlier during his trip in June 1958, and it corresponded to the statutes of the new Constitution voted in September. He was now evoking it as a foil to introduce a third solution :

3° « Association, i.e., Algerians governing Algerians with the support of French assistance and in close union with her... » This last solution, the most chimerical, was the one that de Gaulle had attempted to implement in the other French colonies of Africa and that had failed. On December 11, 1959, he granted independence to Mali, on 15 to Madagascar, and on 31 to Ivory Coast. Dahomey, Upper Volta and Niger were to obtain it in turn.

The war veterans’ “ comité d’entente ” was understandably indignant : « How can we offer secession to French departments ? » This was a violation of the Constitution, several articles of which formally forbade such territorial amputation. The Algerian deputies also protested : « No one can by any means whatever break this century-old unity without undermining the integrity of the national territory and committing a crime. » But the crime would be legalised by means of a referendum organised in the name of the peoples’ right to self-determination : French Algeria, « a historic community to be saved », as our Father used to say, became « a free and debatable opinion; and the lives of millions of people who are related to us, a political idea that could be put to the vote ». 13

The president’s speech had immediate repercussions in Algeria.

As for the Muslims masses, they understood the message : de Gaulle did not want French Algeria, since he did not proclaim it. France was abdicating, while the FLN was imperturbably maintaining its war objective. For their part, the army became alarmed.

JANUARY 1960 : THE WEEK OF BARRICADES

The French people of Algeria, who were becoming aware of the treason of the head of State, joined in greater numbers patriotic organisations like Robert Martel’s Popular Movement of May 13, the “ Mitidja Chouan ”, or Ortiz’s French National Front – he owned the Forum Pub and said aloud what everyone else was thinking.

A new May 13 was brewing : the riot would begin in the street, the army would come round and force the government to submit or resign.

De Gaulle understood the danger... In mid-January 1960, a German journalist, Hans Ulrich Kempski, disembarked in Algiers on the recommendation of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He asked to meet General Massu. The former parachutist won the General’s trust, and the victor of the Battle of Algiers confided in him with bitterness : « De Gaulle does not understand the Muslims. Our great disappointment was to see him become a man of the left. » « The army perhaps committed an error » by calling him up. On January 18, Massu’s remarks were published in a Munich daily. « I was taken for a ride », he miserably confessed. He was summoned to Paris and immediately relieved of his command of the army corps of Algiers.

For the inhabitants of Algiers, the news of Massu’s recall, the last guarantor of the promises of May 13, struck like a bolt from the blue. Ortiz called for a demonstration on Sunday, January 24. For his part, Robert Martel smelled a trap. After having travelled throughout the Algiers and Constantine areas, he realised that the army still placed too much trust in de Gaulle. A new May 13 seemed impossible to him. On January 21, he warned the members of the nationalist movements’ “ comité d’entente ” : « Gentlemen, before you make a final decision, I feel bound to warn you that you are mixed up in a highly provocative governmental operation. That power is seeking to destroy the strength that we represent. De Gaulle needs blood to have a valid reason to stop us and dissolve our movements. » 14

The head of MP 13, whose propensity to illuminism did him a disservice, was unfortunately not heeded and, on January 24, 1960, twenty to thirty thousand people gathered on the Plateau des Glières, which was dominated by the forum esplanade and by the General Government House. It was securely defended by the CRS (state security police) and Colonel Debrosse’s riot police. Ortiz gave up the project of taking it by assault with his territorial soldiers.

In the late afternoon, when the five to six thousand people who were still on the Plateau des Glières began to disperse, Debrosse, who was obeying the instructions of Crépin, Massu’s successor, ordered the police superintendent Trouja to make the standard warnings : « The guard is going to charge. » Trouja refused to give such an order, which seemed madness to him. Nevertheless, the fifteen squadrons of the state police soon descended the forum toward the Plateau des Glières. Suddenly, sustained bursts of gunfire were heard. Some policemen whirled round and collapsed. The squadrons surged back while shooting on the territorial soldiers, who retaliated...

The victims were counted : fourteen policemen dead and a hundred and twenty-three wounded, six demonstrators dead and twenty-four wounded. One detail upset the people who picked up the victims : two-thirds of the policemen had been killed by a bullet in their back.

The truth would be made public a year later, on February 3, 1961 during the trial of the Barricades, thanks to the deposition of Captain de La Bourdonnaye, : « At the beginning of the gunfire, I came out of the General Government House, and I saw two machine guns on the forum shooting towards the Plateau des Glières. » Colonel Godard and General Jacquins had picked up the cartridge cases of the bullets spent. They were all from munition packs that had been delivered to the CRS police the day before 15. The CRS had placed a battery of machine guns atop the stairs that descended towards the Plateau des Glières, so as to shoot in the back of the policemen and in the face of the demonstrators. Both groups believed that they were being attacked by the opposite side.

This was the Gaullist way to trigger an exchange of gunfire and make events escalate beyond the point of no return.

At nightfall on January 24, the demonstrators, under orders from Ortiz and Lagaillarde, took refuge behind the barricades that they had built in the university district that had been rigged as a fallback position, and shouted loudly : « Let de Gaulle solemnly declare that Algeria and Sahara are French provinces, let him renounce self-determination, then we will lay down our arms. »

DE GAULLE - DUVAL, THE SAME FIGHT

De Gaulle demanded the barricades be removed by force : « We must not fear bloodshed, if we want law and order to reign and if the State is to survive. » But paratroops protected the insurgents against a possible police attack. Their chief, Colonel Dufour, was categorical on this matter :

« One does not attack barricades behind which there are Frenchmen who call themselves French and who want to die French in a land that is French. »

For the whole week the insurgents held under arms the heart of Algiers, as well as that of Oran, which had come into line. But, on the evening of January 29, 1960 de Gaulle appeared on television screens wearing his uniform to reaffirm the principle of self-determination. Sly and untruthful, he declared :

« If the Muslims one day decided freely and formally that the Algeria of tomorrow must be closely united to France, how can you doubt that anything would cause the homeland and de Gaulle to feel more joy ? When they are to choose between one or another solution, what could be more joyful than to see them choose the one that would be the most French ? »

As his minister Robert Buron remarked, de Gaulle showed himself to be the « prince of ambiguity ». The formula « the most French solution » could just as well mean to make the Muslims French or to grant independence « with joy » to Algeria.

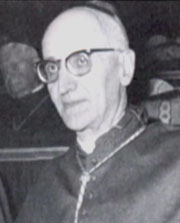

The president of the Republic overcame the resistance of the Pieds-noirs... with the support of the archbishop of Algiers. On Sunday, January 31, Msgr. Duval formally forbade the celebration of Mass behind the barricades, where an altar had been put up. In a message broadcast over the radio he invoked the loftiest of motives : « The honour of God [sic !] requires the unity of all of the children of a same country, in the respect of legitimate authority. » On the following day, the certainty of the insurgents weakened. Msgr. Duval became the spiritual guarantor of the Gaullist abuse of authority, and Challe would not be the providential man of a new May 13.

But a mortal rift also appeared among Catholics, between the faithful and the hierarchy.

A FLOCK DIVIDED

Officially the Church did not take a stand. But Msgr. Duval denounced straight out the « politico-religious amalgamation » of the insurgents, who linked the future of French Algeria to that of the Catholic Church in North Africa, and who increasingly marked the walls of Algiers with Father de Foucauld’s Heart and Cross.

The archbishop had taken care to muzzle all opposition : « In the name of the powers of my responsibility as archbishop, I declare that any priest who exercises the holy ministry in any capacity whatever within my diocese and would take the liberty to publish, without my authorisation, a book, booklet, article (in any newspaper, magazine, bulletin, or even on merely mimeographed sheets) about the political situation of Algeria or the conditions of the presence of the Church and her apostolate would ipso facto be suspens a divinis and a jurisdictione. » (Circular of April 21, 1956)

Since 1956, the Archbishop of Algiers, in agreement with Rome, advocated the Algerian people’s « self-determination » and its attaining independence 16. He welcomed the events of May 1958 with a frigid reserve.

The Mass of Pentecost, 1958 in the cathedral of Algiers, in presence of the generals, was « a trial » for him, but General de Gaulle’s arrival to power was « a relief. When I heard that he had said : “ I have understood you ”, I thought that he was not only addressing the French people of Algeria, but the whole population of the country. He therefore put in this sentence a meaning that the French inhabitants of the city of Algiers did not understand. I believe that I was not the only one to have put my hope in the action of General de Gaulle. »

When he was questioned about the priests of the Mission of France or of Fr. Voillaume’s Little Brothers of Jesus who openly took a stand for independence of Algeria and contributed active support to the FLN rebels, the Archbishop of Algiers answered : « Their position was closely akin to the one that I had taken myself when speaking of self-determination... We sometimes had difficult discussions, but we always agreed on action. »

Fortunately, not everyone shared this outlook. Canon Cabanis, the parish priest of a large parish in Algiers, did not hide his pro-French Algeria feelings. For his part, Fr. Schorüng, the zealous chaplain of Mustapha hospital, waxed indignant over the restrictions that Msgr. Duval imposed on public demonstrations of Catholic devotion, like the ringing of bells :

« How quick you are to liquidate the Christians of North Africa in order to promote Islam and open the door to Communism ! How it grieves you little that Muslims win their paradise of Mohammed by slaughtering and mutilating Christians. How easily you accept that Christians fall under Islam’s power, and become raïas according to Qur’anic law. You have not experienced what it is like. As for me, I experienced it in Turkey, and the history of Greece and Romania taught me what it can be like. » 17

In Oran, the great majority of the faithful and the clergy, particularly Canon Carmouze, shared the convictions of their bishop, Msgr. Lacaste, who associated the French presence with Christian liberty. While in Bône, in the diocese of Constantine, the fiery Canon Houche, archpriest of the cathedral and inspirer of the monthly newspaper Le Petit Bônois also took a stand in favour of maintaining French sovereignty.

Between March 1958 and October 1960, no public declaration of the Assembly of Cardinals and Archbishops of France (ACA) established a firm course of action for the Catholics of Algeria ! « This silence probably results from uncertainty about the future of Algeria, about the politics that General de Gaulle will finally adopt, and whom, moreover, the very great majority of the episcopate is obviously inclined to trust greatly. » 18

While the shepherds of the flock were waiting to see from what direction the “ wind of history ” would blow, or more precisely what direction the tyranny of power would take, priests and religious had no qualms about contributing effective help to revolution and to guarantee it spiritually.

WARPED, BUT CHERISHED BY THE EPISCOPATE

Bernard Boudouresque, a priest from the Mission of France who was on temporary assignment to the Atomic Energy Commission of Saclay, where he militated in favour of pacifism and against torture in Algeria, was arrested on October 14, 1958, for having harboured terrorists in transit to Paris. Cardinal Liénart, Prelate of the Mission of France and President of the Assembly of the Cardinals and Archbishops of France, visited him in prison to express to him his support. Boudouresque was released in February 1959, and his trial never took place.

When the Prado affair broke out during the same month of October 1958, it implicated two Fathers from the Prado and a priest from the diocese of Lyon, Fr. Carteron. They were accused of having supplied the FLN with hiding places; Cardinal Gerlier, Archbishop of Lyon, hastened to shield the three priests.

Priests from the Mission of France joined the Jeanson network of aid to the FLN. One of them testified : « Our aid consisted in being suitcase carriers to put money (the more or less voluntary [sic !] contributions made by Algerians in France) in a safe place. I have personally carried suitcases two or three times to the house of a lawyer friend who lived in the XIIIth district, a member of Vie Nouvelle. One day, Gisèle Halimi needed a cassock and a driver : it was a question of going to pick up an important member of the FLN who had succeeded in escaping from the Fresnes prison, of disguising him as a priest [sic !] and driving him by car to another hiding place. This was necessary because it made it easier to get through roadblocks and avoided possible car searches that were common in Paris. » (quoted by Chapeu, p. 199)

The most representative of these “ partisan ” priests was Robert Davezies, a « physicist by day, suitcase carrier by night », and steeped in Marxism and Teilhardism.

At the end of her study, Sybille Chapeu could write : « General de Gaulle’s coming to power, the man whom the very great majority of the episcopate is obviously inclined to trust, changed the fundamental assumptions. From then on the head of state counted on the most progressivist part of the Catholic Church to make public opinion accept a progressive evolution of Algeria towards independence. . » (ibid., p. 222)

FULL POWERS

De Gaulle immediately exploited his victory over the pieds-noirs in January 1960 by having the Parliament vote him full powers. An “ Algerian Affairs Committee ” was placed under his sole authority; it received exclusive competence on everything concerning Algeria. A prefect of police was appointed in Algiers and Oran. Territorial units and patriotic movements were dissolved and their leaders were arrested.

Throughout 1960, de Gaulle brought into line the military men who had been even remotely involved in the events. Generals Mirambeau, Gribius, and Faure were posted to metropolitan France or Germany, as were also many colonels, including Godard, the man in charge of Algiers’ criminal investigation department since 1957. Bigeard was sent to Central Africa, where he would not have to compromise himself. Others officers were brought to trial.

Challe also suffered the wrath of the Elysée palace before he was able to complete Algeria’s pacification : on April 24, 1960, he was replaced by the very Gaullist Crépin and received command of NATO for Central Europe.

DE GAULLE TO THE COURT !

After the breakdown in the Melun negotiations, the government artificially created the conditions of lassitude that it wanted to obtain in metropolitan France. On September 5, 1960, de Gaulle developed in a speech that aroused wide interest with journalists from the entire world, the concept of “ Algerian Algeria ” : « There is an Algeria, there is an Algerian entity, there is an Algerian personality. » On November 4, he worsened his betrayal : « The rebel leaders say they are the government of the Algerian Republic, which will exist one day, but has never yet existed. » Until then, the Algerian Republic was the symbol, the aim and the property of FLN. From then on, de Gaulle himself championed the cause, indicating that it would « be built with France or against France ».

After the breakdown in the Melun negotiations, the government artificially created the conditions of lassitude that it wanted to obtain in metropolitan France. On September 5, 1960, de Gaulle developed in a speech that aroused wide interest with journalists from the entire world, the concept of “ Algerian Algeria ” : « There is an Algeria, there is an Algerian entity, there is an Algerian personality. » On November 4, he worsened his betrayal : « The rebel leaders say they are the government of the Algerian Republic, which will exist one day, but has never yet existed. » Until then, the Algerian Republic was the symbol, the aim and the property of FLN. From then on, de Gaulle himself championed the cause, indicating that it would « be built with France or against France ».

Cardinals and archbishops broke their silence to hurl poisonous words against the army, insinuating that certain acts « undermined the legitimacy of authority in the conscience of subordinates ». Why did not they point out the lies of those in power ?

On November 16, the government announced a referendum on self-determination and on « the organisation of public powers in Algeria ».

On December 19, the UN anticipated the results of the vote by recognising the rights of the Algerian people to self-determination. Both the United States and the Soviet Union had their interests in it. « The goal of the CIA was twofold : to arm Algerian nationalists against France in order to harvest the fruit of their help after independence. The second aim was, on the other hand, to strengthen the conservative Algerian faction to the detriment of Algerians suspected of Socialism. »19

As the head of state descended further down the rungs of betrayal and abandonment, obscure measures tended to prevent the army from winning the war definitely. The General Delegation released several hundred prisoners, mostly Communists who did not rest until they had rebuilt their cells or fellaghas who would be found once again in the jebel. Dubious characters who sided with the rebels were appointed to the management of social centres and of the SAU (military administrative units in Arab districts).

Numerous soldiers were then convinced that only an uprising could prevent the Élysée palace from carrying out its politics. To defuse the crisis, de Gaulle, accompanied by Louis Joxe, his minister for Algerian Affairs, wanted once again to travel through Algeria from east to west, but without entering into the large cities that were hostile to him. In Aïn Témouchent, Muslims and Europeans welcomed him by chanting “ Algérie française ! ” In exasperation he replied : « Shouting and clamouring do not mean anything. » The inhabitants of Algiers let their anger burst out by declaring a general strike and by demonstrating in front of the Summer Palace.

Numerous soldiers were then convinced that only an uprising could prevent the Élysée palace from carrying out its politics. To defuse the crisis, de Gaulle, accompanied by Louis Joxe, his minister for Algerian Affairs, wanted once again to travel through Algeria from east to west, but without entering into the large cities that were hostile to him. In Aïn Témouchent, Muslims and Europeans welcomed him by chanting “ Algérie française ! ” In exasperation he replied : « Shouting and clamouring do not mean anything. » The inhabitants of Algiers let their anger burst out by declaring a general strike and by demonstrating in front of the Summer Palace.

The Gaullist retaliation was bloody. On December 11, the government, by the intermediary of young Gaullist officers of the SAU, provoked Muslim counter-demonstrations that were soon controlled by FLN agents. Muslims took to the streets of Algiers with FLN flags unfurled and shouted : “ Algerian Algeria ! Long live de Gaulle ! ” They streamed towards the Europeans districts before the benevolent eyes of policemen. The demonstration soon degenerated into a riot. The toll was heavy : 120 dead and 1,000 wounded. Paratroopers and the Legion had to be called in to restore order. Seething with rage, its soldiers said to one another : « What ! the Casbah that Massu pacified three years earlier, that is what thirty months of Gaullist politics have done to it ! »

De Gaulle left a trail of blood in his path, and a serious crisis within the army. Purges, transfers, dismissals in the guise of promotions, mixing of regiments, etc. de Gaulle used all the means at his disposal to make the army the instrument of his will. Although unable to subjugate it, he succeeded in dividing it.

JANUARY 8, 1961 : THE SNARE

« Your referendum is a snare set for the nation », Senator Barrachin said with indignation. The head of state asked the French to vote for him by plebiscite simultaneously approving self-determination and establishing a provisional executive in an Algerian Algeria linked to France. It was, Tripier remarked, « to prepare, in practice, the accession to power of the FLN. But without admitting it. »

On January 8, 1961, the “ ayes ” prevailed, but it was far from a clear-cut, overwhelming victory. In Algeria, participation was small : 40 % of registered voters. If 69 % voted yes, « nine-tenths of these affirmative votes, Rieunier noted, came from Muslims confident in France, whom the French army itself had lead to the polls ».

CENTURIONS READY FOR REVOLT

After the partial failure in the referendum, General Crépin was disowned and replaced by General Gambiez. He was called “ Professor Nimbus ” because of his small stature but showed that he was a man who had zeal equal to the height of his ambition. In the units, however, discontentment was displayed more and more openly : company commanders buried their dead while pointing out that they had fallen for « French Algeria ». The spectre of the abandonment of Indochina haunted their minds : to betray their oath a second time, to abandon to their worst enemies those who had put their trust in France and in the word of honour that they had uttered in her name, no ! They would never accept it.

In fact, the plot was being prepared in plain sight. For these officers, whose decision was now well determined, it was a question of finding men and choosing a leader, if possible a political head. Alas ! This is what was lacking...

The Parisian colonels soon understood that they ought not expect anything from the paratrooper generals Saint-Hillier and Autrand, who headed the 10th and 25th DP [paratrooper division]. On the other hand, several corps leaders gave their consent : those from the 1st and the 9th RCP [Chasseur Paratrooper Regiment], of the 2nd and 8th RPIMa [Naval Infantry Paratrooper Regiment]. The two foreign paratrooper regiments, which had been purged, were undecided, while the others units of the Legion exuded nothing but French Algeria. Colonel Brothier, the corps commander of the prestigious 1st REI [Foreign Infantry Regiment] at Sidi-Bel-Abbès, headquarters of the Legion, declared himself ready for the coup. His participation would be decisive.

In the district units, almost all the officers were inclined to French Algeria, but the troops, particularly the conscripts, did not have the same motivations. The colonels who were involved in the plot chose to overlook the “ rank and file ”. They relied more on the SAS officers, but they were nothing without the district troops. The undertaking would prove to be risky, to say the least. General Gracieux, who agreed in spirit with the cause, maintained that it was doomed to failure. As for Captain Coiquaud from the 1st REP, he was under no illusion : « We have no chance. Metropolitan France will not follow. The conscripts still less. But count me in with the regiment. Camaraderie and honour oblige. » They would both give faithful support.

THE LACK OF A LEADER

What was lacking above all was a leader who was unanimously accepted and who would be able to create a groundswell of opinion in favour of French Algeria. Massu, who only thought of his future, declined to act. Marshal Juin, who was approached, shied away. As for Jouhaud, a pied-noir enamoured of his native soil, he was ready to be involved in the revolt. It is he who wove and connected the links for the plot in Algeria. He was in touch with Zeller, the former chief of staff of the land forces and formerly of the Army of Africa, a practising Catholic who was ready to get involved in the coup against de Gaulle.

After his forced retirement in June 1960, General Salan took up residence in Algiers. That by itself was a statement of sympathies : he would never abandon this French province. In September, he declared to the Association of the Combatants of French Union : « No authority has the power to decide to abandon any portion of the territory where French sovereignty is exercised. » 20 The Gaullist power reacted immediately. Banned from Algiers, Salan took refuge in Spain.

It was Challe who agreed to assume responsibility for the coup. But he laid down his conditions to the colonels. Blood should not be shed, and the revolt would have to be limited to Algeria alone. Considering that it was a serious mistake, Colonel de Blignières insisted that the coup be organised jointly in metropolitan France.

General Challe did not want to hear about it. He only thought of « regaining command of the army of Algeria, implementing his plan that had been interrupted a year earlier, thus showing to General de Gaulle that Algeria’s pacification was possible, and a few months later handing the pacified territory to him on a silver platter ». How unrealistic !

« Some circles fear, Colonel Vaudrey told him, that we will establish a military regime.

– Let’s talk seriously, Challe answered. You know full well that I do not have any personal ambition ! I am not yet an old general like the other one, but I am definitely an old republican. »

THE “ PUTSCH ” OF APRIL 22, 1961

On April 11, 1961, de Gaulle announced in a speech the imminent « disengagement » of France, and talked about a « sovereign Algerian State ». The die was cast. On April 21, Challe landed in Algiers in secret.

On April 22, at 2 a.m., paratroopers occupied Algiers without encountering any opposition. In a few minutes, they seized all the strategic positions. In the Pélissier barracks, General Vézinet, commander of the Algiers army corps, was overpowered, while in the Summer Palace, the general representative Jean Morin was kept locked up. Both of them were transferred to the Sahara for “ vacation ” in In-Salah with General Gambiez, the former commander-in-chief.

At 8 a.m., Radio-Alger, renamed Radio-France, broadcast Challe’s proclamation : « Officers, non-commissioned officers, policemen, sailors, soldiers and aviators : I am in Algiers with Generals Zeller and Jouhaud and in touch with General Salan in order to keep our oath : to protect Algeria. The army will not fail in its mission, and the orders I will give you will not have any other aim... »

Challe had only spoken to the army. He would not mobilise the population who could have, as it did for the May 13, 1958, exercised a decisive influence. Yet, all the day long, the five syllables of Al-gé-rie Fran-çaise were chanted on the main thoroughfares. The paratroopers were wildly applauded. What no one had dared hope for had happened : the army, at least the generals, had revolted ! But Challe, their chief, refused to “ compromise ” himself with civilians.

Reintegrating his office of commander-in-chief, he thought his presence alone in Algiers would be enough to rally all the field officers. He negotiated with his former subordinates by phone. « On the phone, Challe discusses, promises. He grants time to think that will allow hesitation and promote a wait-and-see attitude. Ah ! Had not the time to command come ? » 21

This is how he obtained the adherence of fifteen regiments, but at the two extremities of the country the revolt was poorly engaged.

On Sunday, April 23, at 10:30 a.m., General Salan landed at Maison-Blanche. « Challe had intentionally wanted his arrival to be surrounded by discretion. His appearance could have caused an imposing mass demonstration. The three generals would have welcomed with great ceremony the outlaw coming back from Spain, a ceremony that the press agencies from the entire world would have reported. But Challe, once again, feared to make a political gesture. » Disciplined, Salan settled into the general Delegation to assume control of the civil power with Zeller.

At first demoralised, or pretending to be so, de Gaulle listened to his two emissaries, who informed him of the wait-and-see policy of a large number of soldiers in Algeria. Then he decided to strike a decisive blow to the revolt. At 8 p.m. that same evening, he launched his appeal on the radio : « An insurrectionary power has established itself in Algeria by a military pronunciamento... This power has an appearance : a quartet (in reality, de Gaulle mistakenly used the French term quarteron, which does not mean a group of four but a quarter of a group of one hundred) of retired generals. I order that all means, I repeat, all means be used to thwart these men. » It was not Challe the revolutionary prepared to use all means, but de Gaulle, for the misfortune of Algeria !

Challe, who had at his disposal the most powerful transmitting station of France and Africa made no reply. Radio-France continued to broadcast military music. Even among Colonels Masselot’s and Lecomte’s paratroopers, the speech of the head of state followed by the silence of the generals in Algiers had a disastrous effect. On the following day, these two units were at the point of breaking up. Challe could have taken a measure that would have put all the conscripts on his side. If he had announced their imminent return to metropolitan France, they would have shouted : “ Long live Challe ! ” Re-forming Territorial Units and calling up several classes in Algeria would have given the army more than enough combatants. But Challe did nothing, nothing, nothing.

On Monday, April 14, the bad news mounted : one after the other, air crews regained metropolitan France. In Blida, mechanics hoisted the red flag. Elsewhere, conscripts sabotaged equipment or locked up their officers. In metropolitan France, Communist demonstrators shouted : « Death to the army ! » The fleet of Toulon was given the order to move on Mers-el-Kébir.

The leader of the “ putsch ” – who strictly speaking was not exactly the leader, since there had been no political coup d’état – had lost the game from the moment that he had set these limits to his action : no blood, no split in the army, no civil war.

On the fourth day, Tuesday, April 25, at 3:30 p.m., Challe called Zeller : « Nothing gives hope of a turn in our favour. A vacuum and inertia have been for me a formidable opponent... I have decided to put an end to the military revolt and to hand myself over to the authorities. » Hearing the news, the officers were dismayed. In the evening, a pied-noir shouted on the radio : « Betrayal ! Betrayal ! People of Algiers, everyone to the Forum… Everyone immediately to the Forum… We have to prevent the betrayal from prevailing. » A hundred thousand Europeans answered the call. The four generals appeared on the balcony and tried to talk to the crowd, but someone had unplugged the microphones. The generals withdrew. It was the end.

THE HONOUR OF THE LOST SOLDIERS

The consequences of the revolt were bitter. Challe and Zeller ended up in La Santé prison, locked up in the cells previously occupied by Ben Bella and his associates. Challe was not sentenced to death, as military law stipulated, because of the secret agreement reached between his lawyer, the President of the Bar Arrighi, and the government, in order to remain silent about the burning question of Si Salah...

As for Salan and Jouhaud, they went underground, thanks to the network of Robert Martel and his friends. For them, the fight continued, under another acronym : OAS. In the meanwhile, the army’s spearhead units were dissolved, their corps commanders were condemned. With them, hundreds of the best officers were sacked for having tried to save French Algeria. If they came out of proceedings holding their head high, they went away with a wound that would never heal. De Gaulle called them the « lost soldiers ». Honour to them !

How can the failure of the putsch be explained ? The lack of the insurgents’ firmness towards those who hesitated or who were opposed and Challe’s glaring weakness certainly have something to do with it. General de Gaulle’s determination in Paris contrasts with it to such an extent that some people have deduced that he knew what was brewing and that he let it happen in order to lance the boil and allow his opponents to unmask themselves. They had not understood that they had to « strike at the head ».

The fact remains that de Gaulle knew diabolically how to use every means to make his criminal designs triumph, heedless of the bloodshed and his word of honour. The recourse to a referendum, a democratic means par excellence, served him as a legal justification to impose his policy of abandonment. Being a demagogue, he also counted on the corruption and apathy of the French people. Nevertheless, our Father recalls :

« An historic community, a sacred law, an innocent life cannot be put to the vote and thus depend on the crowd’s free opinion. To subject them to it is already a crime. It is a sin against neighbour and against God ! »

But no one was there to call it to mind. It is already revolting that no man of the Church rose to denounce the betrayal of this man of iniquity and the cowardly abandonment of a whole people. But the worst was the baneful ideas in the name of which this crime was perpetrated. Fr. de Nantes exposed them in his Letter to My Friends on January 1, 1961 and, by pointing to the cause of the evil, he restored hope :

« Let us remove from our hearts and minds all that corrupts the Faith and weakens the Church and the Country, removing them from God’s help and from the natural conditions for their salvation [...]. Falsehood is everywhere, arming fratricide. A new theology takes the place of the ancient one, whose originality is to advocate unconditional respect for Man and thus to subject the civilised Christian who is stupid enough to listen to such ecclesiastical discourses to the barbarians who do not care. A new morality passes into our seminary books that strives to paralyse Christian or civilised armies in their defensive combat, to the benefit of Muslims or idolatrous outlaws invested a priori with all virtues. A new Christian politics is dawning that proposes to free the Church of a western world that is collapsing, so that this unscrupulous backing out earn for it the goodwill of its avowed enemies... Judas tactics ! »

For his part, Father de Foucauld had said with tears : « If you do not make Christians out of them, you will not make them into Frenchman… Before fifty years are out, they will drive you out. » The prophecy dates from 1912. Thus the anticipated year was... 1962.

Brother Francis of Mary of the Angels

1. Fr. Georges de Nantes, Letter to My Friends n° 246, May 13, 1967.

2. Fr. Georges de Nantes, Letter to My Friends n° 166, March 11, 1964.

3. Claude Paillat, Le dossier secret de l’Algérie, 1961, p. 26.

4. Michèle Cointet, De Gaulle et l’Algérie, 1995, p. 43.

5. Pierre Gaxotte, Histoire des Français, 1972, p. 791.

6. The Appeal of June 18, 1940 was Charles de Gaulle’s famous speech in which he declared his rebellion against the legitimate government of Marshal Pétain. Although viewed by many as the beginning of the Resistance and the Free French, historians have shown that the appeal was heard only by a minority. The BBC did not even deem the speech important enough to be recorded, and few actually listened to it.

7. Cited in Isorni, Lui qui les juge, 1961, p. 42.

8. Fr. Georges de Nantes, Letter to My Friends n° 166, March 11, 1964.

9. C’était de Gaulle, 1994, t. 1, p. 58.

10. Mémoires, t. 4, p. 137.

11. Cointet, p. 39.

12. Paillat, La liquidation, p. 508.

13. Fr. Georges de Nantes, Letter to My Friends n° 114.

14. Claude Mouton, La Contrerévolution en Algérie, 1972, p. 403.

15. Cf. Michel Sapin-Lignières, “ Les barricades ”, L’Algérianiste, n° 76, December 1996.

16. Cf. Il est ressuscité ! n° 54, February 2007, p. 22.

17. Archives of the Little Brothers of the Sacred Heart.

18. La guerre d’Algérie et les chrétiens, Institut d’histoire du temps présent, October 1988, p. 40.

19. Mr. Faivre, Le renseignement dans la guerre d’Algérie, 2006, p. 244.

20. Rieunier, p. 240.

21. Pierre Sergent, Ma peau au bout de mes idées, 1967, p. 266.