THE ALGERIAN WAR

5. THE BATTLE OF ALGIERS (1957)

AT the height of the summer in 1956, the FLN leaders « […] drew up their plan of action for winter 1956-1957 : the accent would be placed on urban terrorism, using bombs and grenades, directed mainly against Europeans. In the climate thus created, a general strike would be launched at the time when the Algerian question would be discussed before the General Assembly of the United Nations […]. The whole plan was well thought-out : to take cities as the theatre of operations, priority was given to the main ones and principally Algiers, to defy French sovereignty in its citadel. The goal was to bring revolutionary combat under the very eyes of resident journalists and foreign reporters in the nerve centre of the country; it was thus to place the action in the best resonance chamber. » 1

Thus was begun the « Battle of Algiers », whose fiftieth anniversary we celebrate this year. The French army, grappling with savage terrorism, came out victorious, but at what a price ! Did it lose its honour, as it continues to be accused by those who want to efface the traces of their own wrongdoings ? No, absolutely not, and we will prove it. Yet perhaps it lost « a little of its soul » (Colonel Allaire, then captain in the 1st REP [Foreign Paratrooper Regiment]), in this « spiritual tragedy », to which Fr. François Casta, paratrooper chaplain of the 25th paratrooper division bears witness.

THE ARMY’S SPIRITUAL TRAGEDY

« The paratrooper engaged in revolutionary war came up against some very precise difficulties and temptations caused by the repression of urban terrorism or the pursuit of bands across the jebels. They both originate in certain shortcomings. There was only one way to make the difficulties inoffensive and to forestall the temptations : it would have been necessary for a courageous team of thinkers to have undertaken to resolve them before it was too late. They should have instead eagerly undertaken this search in order to clarify it. Many thought it preferable to denounce constantly as an intentionally maintained complicity with evil, the most rigorous efforts that some of the best officers attempted. These officers’ goal was to take back from evil all that we abandoned to it in our haste, urgency and lack of preparation of police action for example. Yet, against an unscrupulous adversary, we found ourselves disarmed… » This was the tragedy experienced by the army.

The chaplain gives more detail further on : most of the officers, who were Christians, « sincerely thought that the whole problem rose to the level of the defence of the Faith. They refused to believe in the mystification of certain Christian milieus by Marxism and in the illusion of a subsequent evangelisation. Beyond all temporal consideration, we are unable not to remark that everywhere the French flag was brought down, it was the Cross that fell sooner or later. » 2

This “ wound of the soul ” was curable, for this tragedy had its causes, perfectly pinpointed by Fr. de Nantes in two articles of l’Ordre français that were written during the summer of 1957, at the very moment of the events : « Our task in this study, he wrote, will be to cure the ill consciences by reminding them of the highest and most sacred requirements of the right of nations and the good of peoples. We shall judge the morality of each man’s actions in light of this. »

This study from which we are going to quote long excerpts does not only have historical interest, it is the issue of the hour. Valeurs actuelles in fact entitled its issue of January 19, 2007 : « Algiers-Baghdad, the same battle… How can urban terrorism be repressed ? The battle of Algiers is generally thought of as a textbook case. It allowed the elimination of the FLN, the seizure of arms, the return to security. » Let us see how.

WOLVES IN THE CITY

In execution of the Soummam plan, the FLN created a Zone autonome d’Alger [(ZAA) Autonomous Zone of Algiers], headed by Larbi Ben M’Hidi, one of the “ Historical Nine ”, whose watchword was : « A bomb is worth more than a long discourse. » He immediately took charge of the two to three hundred assassination specialists and the thousand henchmen, liaison officers, fund-raisers and political commissioners already established in Algiers. The Casbah, that city within the city with its maze of narrow streets, dead ends, and stairs, had become the fief of the rebellion from the beginning of 1956. Yacef Saadi was Ben M’Hidi’s right-hand man. The Casbah formed a forbidden zone where the police no longer ventured. From his HQ situated in the Granada dead end – quite the symbol ! – Yacef launched his commandos in the city. From June to August 1956, 150 attacks bathed it in blood.

Communist commandos provided Ben M’Hidi with his first women bombers, Raymonde Peschard, a social assistant, and Danielle Mine, who were both mistresses of Muslims, passed from the scout movement to rebellion. Under veils borrowed from Arab women, who were never subjected to searches so as to preserve Muslim modesty, they transported their engines of death with impunity.

On September 30, 1956, the bomb offensive was launched. The objective was the heart of the European city. The devices that were placed in the Cafeteria on Michelet Street and at the Milk Bar killed three persons, and wounded fifty, twelve of whom had to have limbs amputated. In reprisal, the Europeans killed two Muslims. This was what Ben M’Hidi was seeking : to put blood and hatred between the communities. From October to December the horror increased daily. The attacks numbered a hundred and twenty-two by December 1956; that is four per day !

Algiers could no longer bear it and shuddered each day with horror and fear. A third of the attacks were aimed at Europeans in an indiscriminate manner; the remainder was directed against Muslims.

To think that certain Frenchmen already considered these terrorists “ combatants ”, and even “ martyrs ” !

THE CRIMES OF THE REBELLION

« Are the crimes of the rebellion moral ? Asked Fr. de Nantes in his first article of September 1957. The total of assassinations, fires, destructions and various damages, finally physical and moral torture for which the party of the Algerian rebels had made themselves responsible since November 1954 was impressive. No one contests this overall view; every day adds new examples. As in Indo China, then in all of North Africa, in accordance with Communist revolutionary war methods, armed groups went underground after a few meticulously prepared acts of terrorism, while in the cities the cells of extremist parties acted clandestinely to control the masses and organise sedition.

« It is also indisputable that these insurrections were not the spontaneous movement of an entire people united against the French or European oppressor. A century-old public order reigned in Algeria – and still reigned widely – that the military or political weakness of France would have several times handed over to the mercy of the Muslims if they had unanimously detested her. It seems impossible to me to attach the least value to the Marxist schema of universal class struggle for Algeria, where an historical Arabo-Berber nation would have been oppressed and proletarianised by colonial capitalism...

« From the beginning, the rebellion chose torture as the essential means of combat. It sought its power in the brutality of its massacres and plundering, acts that were capable of throwing immense zones of population into fear and horror for want of the ability to reach them by persuasion and enthusiasm. To this end it unleashed the sadism that lies dormant in every man and the barbarian fanaticism of the Muslim souls of the Maghreb. It is possible to count the acts of physical torture, but the number of acts of moral torture and blackmail that reduced people to a state of fear is impossible. And yet, this is the subject that is most important in the eyes of the moralist because it is what leads souls to abdicate their liberty and their honour. The Muslim who does not execute FLN orders, who works for the French, the man of the middle-class, the merchant who does not pay their contribution to the rebellion, the French, Italian or Spanish colonist who is too poor to abandon his isolated farm, like the North African in metropolitan France who is prey to racketeers or enjoined to leave for the maquis in the Aurès, all these poor people, theses hundreds of thousands of poor people know that they are condemned, and feel spied on… They live in anxious expectation of this minute of terror when fanaticism full of hatred would swoop down on them. If there are “ human persons ” to defend, it is these people.

« Perhaps one will say that these attacks and tortures were, for such a small party of rebels, the only way to impose themselves on an inert, heterogeneous mass, to force back a powerful adversary, to get accomplices, funding, and troops that are essential for combat. I do not see that this is an excuse. To declare that in order to hold out and even prosper the rebellion required the shock caused by this state of terror, this perpetual blackmail based on the threat of assassination and pillage, is to acknowledge that from the beginning it was nothing but a revolutionary party lacking the support of public opinion and to admit that there existed a stable, peaceful order that was on the whole very human and with which the masses were satisfied. As for them assuming alone the destinies of their country, this is a pretension that cannot be granted to rival parties who furiously kill one another.

« No idea, however noble it may be, no metaphysical or religious good, no individual interest, can justify such a fight. Those who resolved to do it, those who undertook and pursued it outlawed themselves from humanity; no religious or political authority can have dealings with such people without profoundly shaking the moral foundation of society […]. Whatever future events may be, the rebellion would remain for the conscience of any righteous man criminal in its enterprise and in its methods, with no right of appeal. »

Nevertheless the daily gains of this rebellion were proportional to the failure of the public powers, who should have eradicated it from the beginning.

SHORTCOMINGS OF THE POLICE AND JUSTICE

The three reserve companies of the CRS were far from being able to suffice for the task.

More worrisome was the unsuitability of the methods of police investigation and judicial procedure in the face of the subversive war that the FLN created. « Against such an organisation, only a true, immediate and exemplary justice would be effective. » 3

Now, the trials were too long, came to no result, or most often only sanctioned confederates. Evidence of guilt was rarely assembled, since witnesses feared to testify because they dreaded reprisals. When there was a judgement, the condemnation came too long after the facts to serve as an example.

« Whether the assassin was freed by having his sentence suspended, having his case dismissed for lack of evidence, or by receiving an early release, he then came back triumphant to his fief and had nothing more urgent to do than to kill his presumed denouncers, so that, in the FLN camp at least, certain justice might be exemplary. » It was the same for the measures of clemency decided on by the government in a spirit of conciliation. « For the Muslim soul, leniency is only permitted to the victor; when exercised before its time, it is a sign of weakness and justifies the crime. »

Yacef Saadi himself had been arrested in 1955, but since no charge was yet hanging over him, he benefited from a ruling that dismissed his case.

APPEAL TO THE ARMY

At the beginning of January 1957, the rumour of an insurrectional strike launched by the FLN began to spread in the city. The CCE attached great importance to it because it was to take place at the time when the Algerian “ problem ” would be discussed before the UN. Soon, a great number of tracts confirmed the launching of the strike. Those who would not obey would open their stores or go to work would be ruthlessly killed by the “ brothers ”.

But the Resident Minister, Robert Lacoste, also decided to react and entrusted the new general-in-chief with the mission of coping with the situation. Raoul Salan, fifty-seven years old, was the most decorated officer in the French army.

For the time being, Salan posted at Algiers the 10th Paratrooper Division of General Massu, who had scarcely returned from the Suez operation that had ended in a complete fiasco. Our paratroopers were bitter. Massu, their leader, who had travelled all over since 1940 under the colours of Free France, said so to anyone who wanted to hear it. Yet, on January 7, 1957 it was to him that Prime Minister Bourgès-Maunoury, Max Lejeune, Minister of War, and Robert Lacoste, resident general, delegated powers in order to re-establish order in Algiers « through whatever means ». Massu accepted the mission, without concealing that there « was going to be plenty of hassles… »

FAILURE OF THE INSURRECTIONAL STRIKE

The most urgent problem was to break the strike announced for January 28. Massu organised the counterattack. Two companies of the Army Service Corps (150 GMC) were to assure public transportation of workers. Stores would be opened by force, with sanctions in the case of resistance. On Saturday 26 the terrorists launched a pre-emptive attack by exploding three bombs in the cafés of the city centre. The following day, Sunday, bomb attacks multiplied throughout the city, a convoy fell into an ambush in Affreville, and colonists were assassinated even in the inner suburbs of the capital. The test of strength had begun. Massu ordered more frequent body searches at store entries and in public transportation, imposed a curfew, and had three hundred new suspects arrested.

At dawn on 28, the army went into action. The picking up of workers was a success.

At dawn on 28, the army went into action. The picking up of workers was a success.

The Dodges of the army tore off with a winch the shutters of the stores that had remained closed. Rapidly the storekeepers opened on their own. By the end of the afternoon, a Muslim confided to an officer : « Sir, today the army has routed the FLN. It should have done so long ago, since for us life was no longer possible. » The following day the army was there again, but it had no need to use force, for the Muslims went to work spontaneously. It sufficed for them to be able to say to FLN agents : « I was forced by the soldiers. »

Massu had also thought of school bus service. Candy, military music, nothing was spared. The kids smiled, held out their hands to the soldiers, tore down the stairs to follow the music of the 9th Zouaves. On February 1st, 70 Muslim children went to the schools of Algiers; on February 15, they were 8,000; on April 1st, they numbered 37,000. The strike had failed without the army having to fire a shot. But the match had not been won yet.

BREAKING UP THE TERRORIST NETWORKS

The strength of anti-terrorist war is intelligence. Thanks to the draft of the organisation chart of the FLN network drawn up by Captain Sirvent, commanding the Zouave battalion established on the heights of the Casbah, Massu was able to tackle the second phase of his mission : to rid Algiers of the rebel organisation. « It was a question of detecting the networks buried in a mass of close to 400,000 Muslims and protected by a forced but general silence. It was necessary, without harming the throng of innocents or even the numerous accomplices acting through fear, to penetrate an extremely compartmentalised organisation; it was necessary to detect the network one link at a time, to pick out the active militants, trace the leaders, and identify the killers. It was necessary, while outsmarting ruses, to discover the hideouts, the caches, the relays, the weapons, the bomb workshops and depots. It is above all a matter of intelligence. » 4

Practically everything had to be improvised. Bigeard proceeded in the following manner : « He arrested thirty young men in the streets of the Casbah, asking them only one question : “ Who raises funds in your neighbourhood ? Where do the fund-raisers live ? ” The certainty of not being suspected of informing – none of them was able to know the answer of his neighbour – and the number of persons questioned resulted in them all giving the information requested without difficulty. They were immediately released. The first level of the subversive organisation was thus discovered. »

The patrols carried out the initial investigations; they conducted interrogations, transmitted information to the regiment intelligence officer, and brought suspects to the HQ. They were asked little information on the attacks that they had committed, but precise details on their organisation. In particular, in order to be able to arrest the leader without delay it was the name of the leader that the subordinates had to give and his place of residence. Results were felt rapidly : between February 14 and 19, Bigeard’s 3rd RPC (Regiment of Colonial Parachutists) dismantled the structure of the bomb network of his sector and recuperated 87 explosive devices.

USING EMERGENCY MEASURES !

It was important for the arrested terrorists to speak immediately. Any delay in obtaining confessions allowed accomplices to move or detonate their bombs. Every good piece of information obtained meant dozens of innocent lives saved. It is thus understandable that our paratroopers conducted “ brutal interrogations ”, when the accused stalled revealing what he knew. At least in the beginning, it was necessary to employ « emergency measures ».

In mid-February, a vehicle check permitted them to apprehend a young man of good family who was transporting in the trunk of his convertible a briefcase containing 50 million francs. When interrogated, he divulged the address where he was to deliver the small fortune. His accomplice was arrested and interrogated, and in turn he indicated different addresses that, when checked, belonged to pieces of wasteland. The interrogation was thus resumed, more violently. Finally the man divulged an address; it was in the European quarter ! Bigeard sent a jeep at full speed. Captain Allaire rang, then broke open the door. A man in pyjamas appeared. It was Ben M’Hidi in person… When interrogated, he revealed that the other members of the Executive Committee had left for foreign countries.

On the morning of March 5, Ben M’Hidi was « liquidated », undoubtedly on the order of the Secretary of State for War, Max Lejeune and of the Governor General. Instead of publicly executing him as he deserved, the authorities preferred to get rid of him by letting it be thought that the terrorist committed suicide in his cell. No one was fooled.

Despite this “ blunder ”, the result of the repression on March 31, 1957 was spectacular : 253 killers and 1,574 agents were arrested, 88 bombs and 200 kg of explosives were recovered. The number of attacks dropped from 112 in January to 29 in March. In all the places where the rebel organisation had been dismantled, it was reported that Muslims spontaneously provided information. The population regained confidence, not in the generosity of the army, but in its firmness, that is, in its determination to keep the terrorists whom they had arrested under lock and key and to prevent them from doing harm. Many, however, were still waiting to see.

As for the FLN leaders, though acknowledging their failure, they rapidly understood how they could put to good use the media campaign that was getting underway in metropolitan France.

CAMPAIGN AGAINST TORTURE

Témoignage Chrétien fired the opening shot on February 15, with the publication of the “ Jean Muller file ”, the file of a young soldier who had been recalled and denounced the « degrading practices » of his superiors.

Relayed by Mandouze and Robert Barrat, by Claude Bourdet at France-Observateur, Beuve-Méry and Henri Marrou at Le Monde, Servan-Schreiber at the Express and by the communists at L’humanité, the campaign became more intense in March. It was out of the question for these newspapers to publish articles or photos about the massacres perpetrated by the FLN because, according to them, « it could shock the sensitivity of the French » (sic !)

To an officer who proposed that he should go to Algiers in order to be able to talk about terrorism and its repression with full knowledge of the facts, Beuve-Méry, editor of Le Monde, retorted : « Me, go to Algiers ! Never. I want to keep the objectivity that distance permits. There, my judgement would be distorted. »

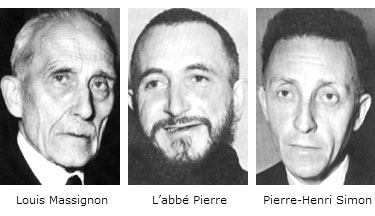

Soon a « Spiritual Resistance Committee » was formed, where could be found mixed together priests like Fr. Pierre, the jurist René Capitant, the journalist Robert Barrat, the historian Charles-André Julien, the Islamologists Régis Blachère and Louis Massignon. They appealed that people fight « against the torture that the army and police services employed in Algeria ». The spirit of the Resistance was reviving ! They published a brochure entitled “ Recalled Soldiers Testify ”, even as there appeared the book by the Catholic writer Pierre-Henri Simon, “ Against Torture ”. It accused the French Army of having borrowed its ideas and methods from Nazi barbarity !

As General Schmitt points out : « As far back as 1958, terrorists presented themselves before the courts as innocents who had confessed only under torture crimes that they claimed not to have committed. FLN officials had understood the advantage that they could take of the campaign against torture launched in metropolitan France. Two assistants of Yacef Saadi, Benhamida Abderrahmane and Zohra Drif had established a standard letter to be addressed to the public prosecutor in Algiers in order to lodge a complaint. Many copies of these form letters were discovered in caches of some ZAA officials who were arrested in September and October 1957. Once the climate changed, the false innocents of 1958 progressively became accusers. » 5

They continued to accuse the French Army through their president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, with the complicity of French leftists and progressivists.

A THESIS PUT TO THE QUESTION

The army never denied that it had used torture in some cases. Some officials of the police (Wuillaume, Mairey) and of the army (Estoup, Massu, Hélie de Saint-Marc) acknowledged as much, as also had two missions of the international Red Cross that were carried out from May 15 to July 6 and from November 23 to December 21, 1957. Torture in the fellagha camp was dreadful. To convince oneself, it suffices to read the autobiographical account of Rémy Mauduit : I was a fellagha, a French officer and a deserter (Le Seuil, 2004). Progressivists claimed that torture was good for the barbarian times. It was their fellagha friends who were bringing us back to it.

It has nothing in common with what the French army was doing at the same time. It obviously fell outside the usual confines of a police investigation made according to the rules, since the enemy imposed on it this new form of fighting : guerrilla warfare. « During the questioning, which was carried out at the very scene of the arrest, explained Colonel Trinquier, the terrorist will certainly not be assisted by a lawyer. If he quickly gives the information wanted, which is usually the case, the questioning is quickly ended. Otherwise, his secret is forced out of him by appropriate means. Now, the terrorist must know this and accept it as a consequence inherent to the conduct he has deliberately chosen. Questioning members of subversive organisations in this way is the only effective weapon to fight terrorism. Any movement that launches terrorism is responsible for what results. » 6

SUMMARY EXECUTIONS

The real assessment of the repression has never been established : in the present state of research, no precise figures can be put forward.

What the paratroopers are especially criticised for is for having carried out summary executions of terrorists during what the soldiers called « wood duty ». Let us recall that these terrorists were perpetrators of assassination attempts; therefore, they were assassins ! If it is true that the paratroopers sometimes took the law into their own hands, it was most often out of necessity. By every possible means, terrorism had to be overcome. « " We can no longer even count on the rule of law to escape from them ! ” declared a rebel leader to a police inspector. » 7

Ben Hamida, political commissioner of the FLN in Algiers, who, in collaboration with French journalists, had launched the campaign « against torture », paid this tribute to the paratroopers : « The population felt protected, and the goal was achieved. At the present time, I can see the system used. I pay homage to these intelligent, strong, and above all humane men. Their conduct toward us was completely noble. »

« To the secret war, the 10th DP responded with secret methods », Massu wrote. It is a great pity, because this secret harmed the action of our paratroopers. In his sector of the Arba that was adjacent to the urban area of Algiers where two murders were committed each week, Colonel Argoud, corps commander of the 3rd African regiment of chasseurs, decided to carry out « some death sentences in public. Contrary to most of the sector commanders who blithely practice “ wood duty ”, I want to act in broad daylight, first because it is in my temperament, secondly because its effectiveness will be increased tenfold. » 8

Argoud did not strike at random; he based himself on the inquests of the criminal investigation department and reported to his superiors each time. After five months, FLN terror had disappeared from his sector. If our leaders had applied this method to the whole of Algeria, abuses committed by certain soldiers like Aussaresses and other rabble would not only have been controlled, but also punished : « 90 % of abuses committed during the Battle of Algiers, Argoud added, are the consequence of this lack of authority. »

THE « CRIMES » OF THE REPRESSION

But morality reproves the use of torture, it will be said ! That remains to be seen. « The great cry of indignation of the Universal Conscience against the odious procedures of repression employed by the French army in Algeria would have had more success in stirring our minds and finding its way into our hearts, Fr. de Nantes wrote, if it had not come from a sect of intellectuals and from a cartel of newspapers dedicated to French abdication in all its forms and at every opportunity. » The moral argument comes within the scope of a vast ensemble of reasons that must all lead to the necessary conclusion : France must leave her colonial possessions as soon as possible and hand them over to democracy and revolutionary nationalism. »

Our Father then attacked the very principle of the campaign against torture :

Our Father then attacked the very principle of the campaign against torture :

« The facts collected and their interpretation were so insignificant for reasoning that our apprentice moralists did not even go to the trouble of firmly establishing them; they were answered on this level of facts either by protesting that the army had never tortured or made anyone suffer, or in reducing or obscuring the most well-established facts... It was to no avail ! If you accept the chosen viewpoint, the major axiom according to which moral law requires you to make omelettes without breaking eggs, you are defeated in advance. The French Army saved Algerian peace and suppressed terrorism in Algiers. These are facts. It is quite obvious that it was by using means other than non-belligerence, holding fire, and secret talks with the enemy, everything the government in the first place, then journalists and satirical moralists seem to regard as the only legal, legitimate and moral means of repression. »

The well-being of the city comes before the corporal sufferings of the citizens, pace the categorical imperative of the so-called Christian “ collective Conscience ”.

« Alas, in our world, one must choose between beating one’s child or raising him badly, between suppressing terrorism or delivering one’s fellow-citizens up to its odious maltreatment, between letting one’s brothers be tortured or practising torture oneself ! Our fine moral conscience does not wish to choose and therefore prohibits us from doing so. Far removed from the actual site of combat, it wants everything and it wants nothing. It is but a wondrous and certain instrument of condemnation against anyone subjected to its scrutiny. And, as you have already guessed, such strictures only ever apply to France, poor France, which must be always in the wrong, always guilty ! Before such a bizarre moral ideal – which is imposed in France but whose laws are never even considered as being applicable to the Russians, the Arabs or the Chinese – we can but be filled with shame. Where does such a morality lead ? To suicide, to the disappearance of the well armed camp of civilisation. Prevented from acting militarily, politically, or diplomatically by the ukases of Conscience, the nation that believes in morality must therefore yield under the pressure of Marxism and Islam, which do not believe in it. »

FOR A CIVILISED MORALITY

Then, Fr. de Nantes recalled the requirements of an upright conscience : « [...] We know the sovereign law of morality, which is the quest for the best good; thus we will not recognise as virtuous actions other than those whose intention will be this best good or some other good in harmony with it [...]. If it is a question of torture, it is first necessary to examine carefully its common nature, its various intentions, and its concrete conditions. Then alone will the moralist be able to say whether it is appropriate or not for the supreme good of men and the order of societies to torture in some occasions or whether it is absolutely necessary to forbid honest men from using such procedures to whatever end and in whatever situation they may find themselves. »

It is this methodical examination that Fr. de Nantes then carried out.

Let us come back to Algeria : « As for the army’s real or imaginary abuses, do they not stem from the same imbalance of forces, some determined and lawless, others paralysed by respect for an anachronistic legal system and by thousands of bans on taking action that continually reached them from superior authorities ! If the government waged war, if justice struck at the head of the rebellion and its accomplices, there would be no need for forces to be deployed with great expense and danger but exposed needlessly, as was seen in Algeria. Yet in such conditions of fighting, it is not surprising that some ill-advised subaltern would exceed his authority, prefer to torture a prisoner rather than to send his company of young soldiers into an ambush, to burn down a hamlet rather than to carry on an unnecessarily bloody siege […]. Responsibility for such actions, then, falls on the rebellion that compelled it and on the negligence of the State that abandoned its soldiers and citizens in such appalling conditions of combat. »

ATTACKS

In Algiers, Yacef Saadi, who was promoted to be head of the ZAA, had re-formed his group of killers. He gave the order to resume the struggle. On Monday, June 3, three explosions shook all Algiers. Powerful charges of explosives had been placed in bases of lampposts near bus stations. Four 155 mm shells could not have done worse; pieces of cast-iron tore the victims to shreds, among whom were many children leaving school. Three of them and five adults were killed outright, not to mention about a hundred wounded who were lying on the ground.

On the next Saturday, June 8, an employee of the casino of the Corniche placed his bomb under the platform where the orchestra was to be seated. At 6 :55 pm, the bomb exploded, causing an absolute carnage among musicians and dancers. The toll was 10 dead and 85 wounded. Algiers’ population was once again plunged into fear, and what brought their exasperation to a climax was that on the same day it was learned that President Coty had just granted a presidential pardon to eight terrorists who had been condemned to death !

This month of June 1957 was the deadliest month of the Battle of Algiers, claiming 231 victims. The Regiments returned, this time determined to put an end to it and to carry out their fight until victory. Civil authorities once again placed all powers (justice, administration, police, and intelligence) in Massu’s hands. He delegated them to his assistant, Colonel Godard. It is this concentration of powers in the hands of one man that ensured the success of the second phase of the Battle of Algiers. Assisted by the efficient and quiet Captain Faulques, an intelligence officer of the 1st REP, a veteran of Indo China and a survivor of the Viet-minh camps, Godard took advantage of the system of urban protection (DPU) set up by Trinquier.

In the meantime, Captain Léger from the 11th Choc had formed a small team of double agents nicknamed “ overalls ” since he had them wear overalls to disguise themselves as workers. This weakening of the enemy’s system formed the second key to success. His men knew perfectly well who were the members of the armed FLN groups. They intercepted them in the middle of the crowd, in cafés, in the Turkish baths, confiscated their identity cards, and ordered them to go in the evening to 21 Emile-Maupas street in the Casbah. There Léger, who was disguised, was waiting for them, and gave them orders diametrically opposed to Yacef Saadi’s orders. The vague feeling of being the victim of some kind of poisoning, then doubt and suspicion took hold of the enemy.

OVER TERRORISM

It was in the night from August 5 to 6 that a certain Ali Moulay, without having been tortured in the slightest but simply under the threat of the guillotine, delivered up all his accomplices. Most of them were arrested, including Yacef Saadi, on September 23, 1957.

The battle of Algiers was won. Attacks would only resume during the summer of 1961, after the unilateral truce ! Thus it was a complete victory over FLN terrorism, which was coupled with an infiltration into the underground of the jebel by certain individuals whom Captain Léger’s “ overalls ” double agent group had convinced to change sides. Very quickly, however, suspicion spread throughout the underground, particularly Amirouche, leader of wilaya III, who did not hesitate to torture and execute alleged collaborators. This mutual suspicion led terrorists to kill one another : three thousand dead in Greater Kabylia, at least five hundred in the Algiers area, mainly officers, whose absence would weigh heavy against the FLN during the great battles of Challe’s plan.

The battle of Algiers was certainly not a pleasant memory for those who took part to it, but it was necessary to fight and defeat the enemy on the terrain he had chosen. « We carried out our duty as well as possible and sometimes in circumstances that we did not wish », General Schmitt wrote. The honour of army is thus intact. But at the end of 1957, Salan had the presentiment that what had been won in Algeria would be lost in Paris. Therein lies the true « spiritual tragedy of the army », the consequences of which few people even today have measured : the betrayal of the Republic and the Church.

THE POLITICIANS’ RESPONSIBILITY

Behind an outward show of firmness, how many dishonest compromises there were behind the scenes ! Many facts prove the governments of Mollet and Bourgès-Maunoury were coming to terms with the rebellion. The most blatant one took place during the summer of 1957. The “ mission of good offices ” carried out by Germaine Tillion, a former resistant linked to the CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique). « It was difficult for my subordinates to understand the parallel activity of Madame Germaine Tillion », Massu noted. We can understand them : at the same time, dozens of bombs were exploding in Algiers. One does not negotiate with terrorists in full action !

The freedom of expression that was granted to the press bore witness to the same political ambiguity and strengthened the terrorists in their hope of prevailing. Arrests of journalists and seizures of daily papers were generally not followed by effective legal proceedings. The FLN made every effort to broaden this current of public opinion that was favourably disposed towards it. Krim Belkacem admitted for example that the press campaign against secret services of Algeria (DOP) had cost him three million francs.

« It is not risky to say, Fr. de Nantes observed, that this work of public security had never been decided on or led as it should have been, imperiously, dominating all other ideological or partisan preoccupation. »

ACCOMPLICES OF SUBVERSION

The treason of the political power is one thing. There existed, however, another one, just as scandalous : the complicity of the Church from the top to the bottom of her hierarchy, under tyranny of “ progressivist Christians ”. The 1st REP discovered with stupefaction their network, and their treason was the object of a trial in July 1957.

Thus, priests hid and abetted terrorists. Their enthusiasm went so far that they did not hesitate to compromise the Missionary Sisters of Our Lady of Africa in order to harbour Raymonde Peschard, who was being pursued by the 1st REP. When the Mother Superior, Sister Marie-Louise discovered through the newspapers what kind of a person she was sheltering, she decided not to hand her over to the paratroopers, but to transfer her to the White Sisters of Birmandreis, and then to the Poor Clares, from where she escaped to go underground.

In December 1957, during the trial of Ben Saddock, the murderer of Ali Chekkal, the former Vice President of the Algerian Assembly, a faithful Frenchman and advocate of our civilising cause before the nations, who was killed only a few feet away from President Coty in Colombes, Father Mamet, a priest of the Mission of France, deliberately took the side of the murderer, « a figure of all the persecuted, of all the exploited » !

SUITCASE CARRIERS

It is this innocuous sounding name that was used during the Algerian war to designate all those who, by rendering services to the FLN, became « accomplices of a highly criminal type of terrorism. Some of them claim their part in the success of the FLN, whose leaders maintain that their war of independence was won in France. » 9

Their main role was to smuggle into Switzerland funds collected in metropolitan France by FLN, which taxed willingly or unwillingly, often unwillingly, Algerians who worked in our factories; they used the same methods as in Algeria : cutting off noses, etc. The fact that these funds finally supplied the moudjahidin with the bullets that shot our soldiers, or the terrorists with the explosives that killed and mutilated innocents persons, did not disturb these “ good consciences ” any more than did the methods used to collect the funds.

In the centre of this loose conglomeration was the Jeanson couple, who created on October 2, 1957 a network in the Petit-Clamart that gathered Communists, progressivists and priests from the Mission of France. The assistance given by the “ Jeanson network ” would be essential for setting up the FLN in France and for the collection of funds for « the brothers » in Algeria.

One day, General Massu went to the Archbishop of Algiers, « Ben Duval », as his soldiers called him, to ask him that his priests cease all assistance to the rebellion. But the bishop took no heed. Then Massu wrote to Pope Pius XII : « May I make so bold as to draw your lofty attention to the difficulties caused by the surprising attitude of our Archbishop, Msgr. Duval, as well as some of his colleagues, notably Fr. Scotto... » In reply, the Pope had his nuncio express « the wish that all sane forces, in a reciprocal trust, may work together to restore peace. » No comment.

THE LESSONS OF THE BATTLE OF ALGIERS

« Let the State save order, and let moralists support it. Their concerted treason leaves our fellow citizens in a bloody tragedy. » It is with these premonitory words that Fr. de Nantes concluded his two articles, specifying in five points what was suitable for a moralist worthy of the name of Christian and French to denounce with courage :

« 1. Criminal rebellion for both its illegitimacy and its inhuman methods of oppression and struggle.

« 2. The political world and the successive governments that give amnesty to criminals and negotiate with rebels, in defiance of their essential duties towards the country and their fellow citizens.

« 3. Everyone in the civilised world or considered as such who makes himself the accomplice of rebellion, and helps it diplomatically, militarily, or financially.

« 4. Intellectuals and moralists who spread doubt concerning the legitimacy of legal order and the validity of repression, in order, on the contrary, to speak in favour of rebellion. It is appropriate to use greater severity in this case towards the French who, in doing so, contravene their patriotic duty.

« 5. Provocateurs, the unbalanced, the extremists, the exasperated who, for the sake of order, or justice, or revenge, or legitimate self-defence, indulged in brutality or appalling acts of counter-terrorism. To know how to weigh up the intentions, envisage the tragic situations of these people whom the entire world seems to abandon, and whom their own brothers are stabbing in the back. »

But this denunciation was insufficient, and after having read Jean Lartéguy’s historical novel Les Centurions, the main action of which takes place in Algiers, our Father, foreseeing that this Algerian war was only a testing ground for the great Revolution, wrote to our senior brothers : « Only the great counter-revolutionary Christian mystics are able not to be disoriented and thus are able to dominate the enemy; only members of Action Française can intellectually and physically hold out, in face of this disconcerting spectacle. Notice that the novelist has the reader regard the disoriented paratroopers, in search of a way to parry this war of ideas but unaware of where to find it. It is not within themselves, nor in political parties, nor, alas ! in the left-wing clergy – the only kind of clergy they know… There is a place for missionary-monks with Father de Foucauld’s spirit, not the modern Father de Foucauld, not the one of Robert Barrat who has just been imprisoned for incitement to desertion, but the real Father de Foucauld, the monk-soldier, the Catholic and French martyr of this double cause in his medieval fort… »

Brother Thomas of Our Lady of Perpetual Help

1. Philippe Tripier, Autopsie de la guerre d’Algérie, 1972, p. 127-129.

2. Le drame spirituel de l’Armée, éditions France-Empire, 1962, p. 107-109.

3. Tripier, p. 153.

4. Ibid., p. 138.

5. Alger-été 1957, Une victoire sur le terrorisme, L’Harmattan, 2002, p. 14.

6. “ Terrorisme et torture, le cycle infernal ”, Historia magazine n° 226, 1972.

7. Cité par Claude Paillat, Dossier secret de l’Algérie, 1962, t. 2, p. 360.

8. La décadence, l’imposture et la tragédie, 1974, p. 150.

9. Commandant R. Muelle, Le livre blanc de l’armée française en Algérie, 2002, p. 146.