THE ALGERIAN WAR

3. THE CAUSES OF A REBELLION (1916-1954)

« A shot rang out in the night; then silence returned. The world was indifferent and took no notice. But, in the Kingdom of God, a new blood flowed, a love poured forth, which enriched this land and these impulsive or criminal men with a superabundant grace of pardon and glory. » (Georges de Nantes, Letter to My Friends n° 23, October 1957)

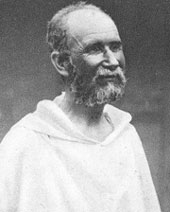

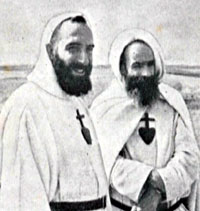

FATHER DE FOUCAULD, SOLDIER OF FRANCE

On December 1st, 1916, at the height of the Great War, Fr. de Foucauld died at an assassin’s hand in front of his small fort, when the Sahara was ready to rise up at the call of Senoussist rebels. For fifteen years he had been the keystone of the order and submission that the enemy, who were in the pay of Germany and Turkey, wanted to undermine.

« He was guided by Love in all things. He forgot himself for the true good of his brothers, without accepting lies or tolerating illusion. He loved France and wanted to make her loved by all. He loved Jesus and His Church, and from the day he rediscovered Them, he wanted all the peoples of the earth to love Them with him. He loved the soldiers of the colonial Army and became their priest and father. He loved the poor people of the Sahara and ardently wanted their good. Their well-being was firstly the French peace followed immediately by direct French administration by those officers who would later form that admirable corps of officers of Native Affairs. […]. He suffered from the Republic for its secular, materialist, centralising policies, for its stupidity and inhumanity. Out of prudence, he could say nothing about it. Without the protection of Laperrine, he would have been banished from the Sahara! He was pained by the apparent irreligion of so many Frenchmen who scandalised the natives and delayed the time of their conversion. More than anything, he detested the master-slave dialectic under whatever form it took, but he knew that it was possible and desirable for deep, religious, human contact to be formed through relationships between the colonised and the colonisers, based on goodness. (CRC n° 107, La Mission Catholique de la France, July 1776, pp. 11-12, published in CCR n° 294, March 1997, pp. 29-30)

THE CRUCIBLE OF THE GREAT WAR

« Like you, he confided yet again to Joseph Hours, I hope that out of this great evil, this war, there will emerge great good for souls […]. A good for our infidel subjects, multitudes of whom are fighting on our soil, getting to know us and growing closer to us, and whose loyal devotion and daily presence inspire the French to be more concerned for them than in the past. They will stir the Christians of France, I hope, to work for their conversion much more than they have in the past. »

The “ natives ”, as they were called at the time without there being the slightest contempt in this designation, proved themselves to be models of fidelity during the four years of the war. When the conflict was announced, voluntary enlistments were so numerous that only a small number of them could be retained. A total of 170,000 participated in this war; 25,000 zouaves, tirailleurs, spahis or African chasseurs gave their lives on the battlefields of the Marne, Champagne, the Yser, and Verdun. The village of Gouraya in Algeria claims the sorrowful honour of being the French town that lost proportionally the most of its children, all races included.

The “ natives ”, as they were called at the time without there being the slightest contempt in this designation, proved themselves to be models of fidelity during the four years of the war. When the conflict was announced, voluntary enlistments were so numerous that only a small number of them could be retained. A total of 170,000 participated in this war; 25,000 zouaves, tirailleurs, spahis or African chasseurs gave their lives on the battlefields of the Marne, Champagne, the Yser, and Verdun. The village of Gouraya in Algeria claims the sorrowful honour of being the French town that lost proportionally the most of its children, all races included.

Provided that they were well commanded, the natives were fearsome combatants, specialised in hand-to-hand fighting and, consequently were used to spearhead offensives. But they were also childlike. In order to galvanise them, their officers had to risk their lives. This explains the enormous loss of officers in units of the Army of Africa.

The grace that our “ infidel subjects ” gained from this four-year war, besides service to the motherland, was to discover her in her profound realities: her villages, fields, trades, and churches. In the mud of the trenches, they rubbed shoulders with her poilus, their commanders, and their chaplains… When they returned to their country, although they had refused schooling their children in the past, they agreed en masse to entrust them to the public, and alas secular, school. These schools were often unable to meet their expectations for want of means.

A DESERTED CONSTRUCTION SITE

A certain number of North African workers who had come to metropolitan France during the war remained there in order to participate in the reconstruction. 65,000 were registered on October 1st, 1918. Better salaries in France and the series of bad harvests in Algeria provoked a formidable exodus, especially among the Kabyles, who suffered from overpopulation and unemployment. 71,028 Algerian entries into France were registered in 1924. Because such an influx of immigrant workers did not correspond to any French economic or political necessity, the rapprochement that Fr. de Foucauld desired did not occur, except in a superficial manner. Uprooted and abandoned to themselves in the suburbs of Paris, Lyon or Saint-Étienne, working for starvation wages that they sent to their family, they became easy prey for Communist union organisations.

In Algeria, Europeans began to concentrate in cities and abandoned farming for want of a sufficient workforce. The lack of the young men who had been killed in the war was also felt. Immigration from Europe fell to almost nothing; on the other hand, population growth among the natives soared. For certain persons who only think in terms of elections and the stupid “ law of numbers ”, it was perilous.

Under the influence of the liberal governors Jonnart, Steeg and company, our colonial policy did not experience anything but superficial reform.

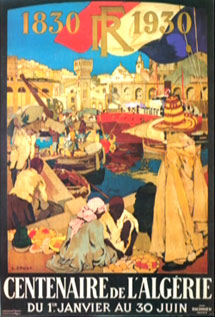

AN ARTIFICIAL AND TRIUMPHAL CENTENARY

The centenary of the conquest of Algeria (1830-1930) made an opportunity for grandiose official parades, elaborate Arab-style equestrian demonstrations, distribution of baksheesh, as well as over-obliging assessments that, although not false, nevertheless maintained a dangerous illusion.

The centenary of the conquest of Algeria (1830-1930) made an opportunity for grandiose official parades, elaborate Arab-style equestrian demonstrations, distribution of baksheesh, as well as over-obliging assessments that, although not false, nevertheless maintained a dangerous illusion.

It is true that in a hundred years the country had been transformed. Large cities had been built to replace the towns of 1830, ports maintained a very active commerce, mainly with metropolitan France, in accordance with the “ colonial pact ”. Due the tenacity of our colonists and the efforts of the French administration the prosperity of the hinterland had made our Algerian departments an undeniable colonial success. French richness and productiveness had been imported into Algeria in a proportion perhaps unique in the world. From the simple financial viewpoint, half of the total capital invested in the colonies was for Algeria, an investment far superior to that of England for her colonies.

Algeria was a colony to be populated. At the time of the Algerian war those who would be called « les pieds-noirs », Algerians of Spanish, Maltese, Italian or French origin, formed a new people. The Church fashioned a common soul for them by means of her works of charity, as also did the blood they shed during the Great War. The Mitidja Plain was their pride and joy. It was the showcase of French colonial work in Algeria. At the time of the conquest, this swampy plain in the area surrounding Algiers was so unhealthy that entry was banned. But the colonists sensed its fertility, worked unrelentingly at draining and clearing it, and brought it under cultivation. Many died from repeated bouts of fever, but the Mitidja soon became this plain of 500,000 hectares that was among the most fertile in Algeria and that was so admired in the 1950s.

« IF THEY DO NOT CONVERT… »

Nevertheless, a few months before his death, Fr. de Foucauld had issued this solemn warning: « My thinking is that if the Muslims of our North African colonial empire are not gradually and gently converted, there will arise a movement similar to that in TurkeyIf we have not succeeded in making Frenchmen of these people, they will chase us out. The only way for them to become French is for them to become Christians. » (Letter to René Bazin on July 16, 1916)

Nevertheless, a few months before his death, Fr. de Foucauld had issued this solemn warning: « My thinking is that if the Muslims of our North African colonial empire are not gradually and gently converted, there will arise a movement similar to that in TurkeyIf we have not succeeded in making Frenchmen of these people, they will chase us out. The only way for them to become French is for them to become Christians. » (Letter to René Bazin on July 16, 1916)

One is rarely such a good prophet...

The following year, on July 13, 1917, the Blessed Virgin announced at Fatima that « if My requests are not heeded, Russia » « will spread her errors » throughout the world. These « errors » include her seeds of revolution, subversion and destruction of traditional order. In order to accomplish this, Russia benefited from the complicity, to say nothing of the connivance of our western democracies. In 1918 the right of peoples to self-determination, « a fundamentally antihuman, antichristian, and intrinsically perverse principle » (G. de Nantes), was proclaimed in President Wilson’s Fourteen Points; it gave the rebel minds in our colonies an ideological basis for their revolt.

Three movements embodied these « errors » in North Africa that drove our subjects to revolt.

« … THEY WILL CHASE US OUT »

First, Islam, as Fr. de Foucauld had foreseen, rose up against French domination. French administrators, steeped in secularism, that is to say, “ State godlessness ”, thought it was good politics to support the heads of the Muslim fraternities in order to control the population by means of them. This “ effortless ” arrangement had a flaw into which the ulemas, Muslim scholars educated in Tunis or Cairo, rushed. By preaching a return to the original Koran, they had no difficulty in showing that submission to France was in contradiction to it, in particular in its precept on holy war, and that pro-French Muslims were traitors.

France allowed the great force that would oppose her to organise itself methodically. Grouped into an association in 1931 led by Ben Badis, a sheik from the Constantine region, these « theoreticians of Islam » founded about 250 Koranic schools, with the motto: « Islam is my religion; Arabic is my language; Algeria is my country. » The “ hard-liners ” criticised them for their being too attached to the advantages of a double game. They nonetheless remained the theoreticians of a “ holy war ” against western civilisation and preferred to hold all the “ separatist ” meetings in mosques.

The second protest movement was of Communist origin and appeared at the beginning of the 1930s. The French Communist Party had proclaimed itself anticolonialist from its founding, and agents from the IIIrd International toiled to « awaken the national consciousness » of colonised peoples against their « exploiting » masters. Even though the Marxist atheism of their propaganda repulsed the Muslims of North Africa straightaway, the emigrants in France let themselves be easily contaminated.

Messali Hadj was one of them. After his demobilisation in 1918, he remained in France, where he began to wander from one factory to another in the Paris region. He then entered University, where he was filled with enthusiasm for Abd el-Krim’s revolt in the Moroccan Rif and joined the Communist Party that was leading the same combat. He received training in Bobigny and in 1926 founded the first anticolonialist party: The North African Star, which set its sights on liberating the peoples of the Maghreb. The virulent propaganda that he deployed against the French, « who exploited native labour », earned him a series of arrests, which were followed by releases, and contributed to creating for him the reputation of a martyr and defender of the oppressed people of the Maghreb.

When his first party was disbanded, he created a new one in 1937 : the Algerian People’s Party (PPA), which became the most violent and cynical of the anti-French parties. In September 1939, Messali was once again condemned; this time to sixteen years at hard labour. By means of his Marxist dialectic, he succeeded nonetheless in inciting hatred in many places where the French had lived for three generations on good terms and in loyal collaboration with the natives. It is also noteworthy that several of his partisans let themselves be won over by Nazi propaganda during the war.

The third current of rebels consisted of individuals who had attended the schools and university of the Republic, and there they had learned the principles of secularism, equality, liberty and fraternity. Among these natives who now bore academic credentials and were eager for responsibilities, the most emblematic figure was Ferhat Abbas. This pharmacist from Sétif who spoke French better than Arabic engaged very early in politics. Diderot, the theoreticians of the French Revolution, and Jaurès were his revered masters. Some claimed that he was “ a moderate ” and quoted his article that appeared in 1936 in the journal L’Entente :

« I will not die for the Algeria fatherland because this fatherland does not exist. I have not discovered it. I questioned the living and the dead, I visited cemeteries, but no one spoke to me about it… One cannot build in the clouds. We have dismissed forever all these mirages and chimeras in order to link our future permanently to the future of the French work in this country. »

In this, he differed from the ulemas who spoke of an « Algerian nation ». But Ferhat Abbas added: « Without the emancipation of the natives, there can be no durable French Algeria. » By “ emancipation ”, he meant access to political life for the « capable » natives… like himself. His discourse varied to fit the political opportunities to the point of accepting in 1955 the exterior direction of the FLN rebellion.

The Messalist party, the Ulema movement, and the Abbas group were the three actors in the drama of Algerian separatism who were then preparing themselves behind the scenes of French political life.

« ALGERIA, SO DEAR TO US »

1930 marked the decisive turning point in the life of the colony. It is from this moment on that Algeria was placed under “ artificial respiration ”, as Daniel Lefeuvre writes in his book “ Chère Algérie, comptes et mécomptes de la tutelle coloniale, 1930-1962 ” (Société française d’histoire d’outre-mer, 1997). « By wringing the neck of a complaint, the repetition of which ended up being wearisome, Jacques Marseille writes in the preface, Lefeuvre proves that France assisted Algeria instead of exploiting her. » (p. 9)

Unable to provide for her needs with her own means, Algeria’s survival depended on importing essential products from the metropole and moving public capital that was rushed to allay growing deficits. At the same time, however, the Algerian population was increasing at an accelerated rate. The beautiful province was no longer able to feed its inhabitants. Algerian farmers were too numerous to live on their excessively small plots of land, which were often poorly worked for want of means. They were leaving their villages to seek work and resources in cities and, not finding any, they crammed into unhealthy slums on their outskirts before moving on to metropolitan France. In 1934, the French language was enriched with a new word: bidonville, the name of a neighbourhood of Algiers; the term is now applied to a “ shanty town ”. The possibility of establishing new industries in the colony was studied, but no project succeeded. The strikes in 1936 and, it must be said, the bad will of French industrialists, who were jealous of their commercial privileges that allowed them to sell their manufactured products inexpensively in North Africa, prevented any serious initiative aiming to modernise the colony.

Instead of imposing measures that were in the interest of the nation, the Popular Front inflamed people and divided Algeria against herself. At the beginning there was the apparently generous project of the former Governor Viollette, which consisted in extending French citizenship to a greater number of Muslims, who were capable or deserving. But this was, from one point of view, an admission that the colonial situation was fundamentally unjust and oppressive and that only emancipation by the paper ballot could resolve the situation. It would subject the “ colonial ” link to the Marxist dialectic and the party struggle, Europeans against natives, which would make obsolete and impossible « this human, profound, and religious human contact that based relations between the colonised and the colonisers on goodness » and not on equality and liberty. The project fell through due to a general outcry of the colonists and the notables, who saw in it an imminent electoral danger.

A bad seed had been sowed. It would suddenly sprout after the war. But in the meantime there were two years of unanimity, a return to good sense and audacious reforms.

UNANIMOUS BEHIND MARSHAL PÉTAIN

The defeat in June 1940 and the announcement of armistice negotiations provoked an immense surprise in Algeria. On June 18, General Noguès, who commanded the troops of North Africa, telegraphed the government: « All the troops as well as the French and Muslim populations of North Africa urge me in moving initiatives to ask the government respectfully to continue the fight and to defend North African soil. The natives in particular, as they declare, are ready to march with us to the last man and would be unable to understand that one might dispose of their territory without attempting with them to conserve it, when in 1939 and 1914 they responded en masse to our appeal to come fight in France alongside us. » Marshal Pétain thought likewise, and the inviolability of the Empire was one of the non-negotiable clauses of the armistice, which he signed « between soldiers and in honour ».

The Army of Africa was maintained, in a half official, half secret manner, under the dynamic impetus of General Weygand, who was sent there by the Marshal « to defend the Empire against whomever ». When the German and Italian armistice commissions came to make their inspection, there was not a single native to reveal the hidden stocks of arms and materiel!

The National Revolution had been welcomed in Algeria with as much enthusiasm by the Europeans as by the natives. It was the occasion for a religious renewal among the Catholics of Algeria: « Votive offices were never so well attended and expiatory processions multiplied. Priestly vocations experienced a sharp increase. The most cloistered and contemplative orders attracted youths. » (Annie Rey-Goldzeiguer Aux origines de la guerre d’Algérie, 2001, p. 89)

The National Revolution had been welcomed in Algeria with as much enthusiasm by the Europeans as by the natives. It was the occasion for a religious renewal among the Catholics of Algeria: « Votive offices were never so well attended and expiatory processions multiplied. Priestly vocations experienced a sharp increase. The most cloistered and contemplative orders attracted youths. » (Annie Rey-Goldzeiguer Aux origines de la guerre d’Algérie, 2001, p. 89)

Among the natives the Marshal enjoyed uncontested prestige. The Bachaga Boualam recalls that « the veterans all had a photo of the Marshal in their hut » (Mon pays la France, p. 98).

A NATIONAL AND COLONIAL REVOLUTION

It is not the least merit of Daniel Lefeuvre’s book, “ Chère Algérie ”, that he rehabilitates the « innovative politics » of Vichy that were applied successively in North Africa by General Weygand and Admiral Darlan.

An initial series of reforms were launched for the defence and restoration of soil and for a better distribution of lands. Yes, it was Vichy that had the audacity to launch a land reform which the progressivists themselves only envisaged with fear!

This was not enough. It was extremely urgent to programme a coherent industrial development plan for the colony in order to offset the shortage of manufactured products resulting from the defeat, to guarantee the native populations’ fidelity to France, and finally to preserve our colonies from « any foreign interference susceptible of manifesting itself after the war ». In July 1941, Weygand had a “ General Programme for Industrialising North Africa ” adopted by the government. The number of industries and variety of infrastructure to be created was impressive: iron and steel industry, agricultural machines, fertilizers, glass-making, agricultural produce. To the government’s call, numerous industrialists from metropolitan France replied : Present!

The wisdom of the measures that accompanied the implementation of the programme proved that the general had succeeded in surrounding himself with good advisors.

Experts from the General Delegation freed of all partisan spirit stated that setting up industries would keep native manpower in Algeria and « would constitute an alternative to the social danger that still unassimilated immigrants present in France, where Communism recruited them as shock troops […]. Those who returned to North Africa brought back with them new seed for the anarchy that lives in the heart of the Berbers and that destroyed the layer of social discipline that French colonisation always brings to native milieus. The Berbers will only progress by sound ways towards French civilisation if they evolve in a coherent social setting, without abrupt rupture with traditional morals, in their own milieu, in the course of centuries. The use of native workers in factories in metropolitan France for several years before the war showed that they were able to adapt very well after a short training period to industrial trades. Some people will be alarmed perhaps by the regrettable consequences that could be feared, from a social viewpoint, occasioned by introducing a new proletariat among Algerian elements. It does not appear, as matters stand at present, that this fact has to have a disquieting influence on our future. The new Algerian working class, directed according to the principles of rapprochement between workers and bosses of the social policy that the Marshal’s government inaugurated, were carefully protected from exterior propaganda and, far from being an element of trouble and disorder, will inevitably constitute a precious factor of evolution for itself and for us. » (quoted by D. Lefeuvre, p. 173)

What wisdom they showed! We will soon see that the FLN, which was defeated by the French army on its own ground in Algeria, only won its revolutionary “ war ” in metropolitan France among these immigrant workers who were left to their own devices. The Marshal desired to implement this corporative project personally when he wrote to Mr. Jean Paillard, the author of a brochure that was published in 1943, The French Empire Tomorrow: « The best colonisation is that which tends, thanks to the corporative order, to have our colonies participate in the social justice that inspires this order. » (quoted by the author, p. 7)

Another noteworthy fact was that the appointment of Muslims as national advisors in 1941 provoked no unrest in the European colony. This reform nevertheless placed Muslims within French political institutions for the first time. The secret was simple: such measures, when dictated by national interest and imposed outside of the parliamentary framework, do not fuel electoral agitation.

« WE ARE AFRICANS! »

The stakes were also strategic in such a development of our colonies in North Africa. We have related how the Army of Africa was built up again under the cover of the armistice (Il est ressuscité n° 36, July 2005). It was at the order of Admiral Darlan, who was providentially present at Algiers at the moment of the allied landing on November 8, 1942, that the army resumed combat operations against the Germans on November 19 and that the natives in turn enlisted, starting on December 11, in this army that was going to liberate the motherland, « in the name of the Marshal, whose hands are bound ».

First it was necessary to reconstitute the strength of the army by means of broad recruiting measures. The Muslim Algerian classes responded to the call with remarkable fidelity, and Moroccan and Tunisian volunteers abounded, even though the greater part of the mobilisation effort weighed on the French of North Africa: twenty classes from 1924 to 1944. Women were even called on to serve as nurses or ambulance women. The integration of the French and the Muslims took place smoothly, in equal proportions.

THE RETURN OF OLD DEVILS

After Admiral Darlan’s assassination on December 24, 1942, hunting down “ supporters of the Vichy government ” and the struggle for power between the supporters of Generals Giraud and de Gaulle paraded before the dumbfounded natives the sad spectacle of our divisions. The separatist parties then raised their heads. Ambitious people like Ferhat Abbas understood that hereafter they should curry favour with the Americans, all the more so because Roosevelt’s politics as expressed in the Atlantic Charter – which was translated into Arabic and a million copies were distributed in Algeria – promised « the emancipation of oppressed people ».

When de Gaulle came to establish himself in Algiers in May 1943, he chose General Catroux as advisor for his Algerian policy. The Blum-Viollette project was again made the order of the day. This time, Catroux knew how to break the resistance of the colonists and the notables: accuse them of “ being supporters of Pétain ”.

Republican equality triumphed. The French Empire was replaced by de Gaulle’s utopia, “ the French Union ” – the colonies would govern themselves in a fanciful « French framework ».

Far from being satisfied, the three movements that followed Ferhat Abbas, Messali Hadj and the Ulemas, went one better by founding a single separatist movement: the “ Friends of the Freedom Manifesto ” (AML). Their campaign of calumnies against fat colonists and “ Vichy traitors ” intensified, and all the while their demands increased, too. Someone had to pay the price, they said, for the tirailleurs, spahis and goumiers that the French generals had requisitioned for their armies. This political attempt to cash in on the heroism of the native troops was scandalous, and moreover, far from the minds of the combatants.

THE FORGOTTEN VICTORY

General Juin, who commanded them, recalled « the memory of the purest heroism and fraternity that always reigned in the ranks of the Army of Africa, so true it was that within it, in the crucible of battle, the two races always mixed extremely well, understood one another, and loved each other the best ».

The legendary figure of this leader of « pied-noir » origin, who was called “ Juin the African ”, will always remain attached to the Battle of Garigliano, which opened the road to Rome to the Allies on May 13, 1944. The patriotic fervour, the solidity, valour and discipline of the units of this French Expeditionary Force in Italy (C.E.F.I.) dumbfounded the Allies themselves. France was coming back to life in the army forged under the African sun, thanks to the Marshal!

Alas! the advance of the (C.E.F.I.), which had moved up to Sienna, was stopped dead. The brilliant strategic manoeuvre that Juin imagined, taking the war in the direction of Hungry through Lombardy, Venetia and the Ljubljana Gap, in order to cut the Soviets from the road into the Balkans and to forestall them in the race to Berlin, was rejected by Roosevelt, who was bound by his agreements with Stalin. The C.E.F.I. was disbanded, and its units re-embarked in order to go form the 1st French Army which, under the orders of General de Lattre de Tassigny, who was more in favour with the C.F.L.N. in Algiers, was to land in Provence. Despite this strategic mistake of incalculable consequences, these contingents had very high morale, drove the defences of Toulon and Marseille from the field, and advanced up the Rhone Valley.

But soon, in the area of the Vosges, the German resistance became more entrenched. The 1st Army still remained “ the Army of Africa ” in its officers, its troops and especially in its spirit, and was accustomed to fighting at the sides of the Allied armies and to using the most modern arms. All by itself it was able to confront the German army. Once more de Gaulle, who had taken power in Paris, kept this unit on the front line; the result was that in mid-December 1944, the losses in its ranks were dreadful.

Were these sacrifices sufficiently known and understood? No, alas! because silence was the rule concerning the soldiers of the Army of Africa, when the FFI and the FFL, for their part, saw themselves covered with praise. Incredible discrimination took place in the advancement of officers, furloughs, all the way down to the level of clothing: units were seen fighting in snow still wearing the summer uniforms they had worn at debarkation, while “ new ” elements that had never engaged in combat or been engaged on passive fronts, were equipped with American clothing.

Today, this “ oversight ” allows the film “ Indigènes ” to put the blame for this injustice on colonialism and the French army, while it was on the altar of the Gaullist myth that their memory was sacrificed.

FORERUNNERS OF CIVIL WAR

Let us return to Algeria, where the economic situation was worsening from day to day. Mobilisation on the one hand, the purge on the other had deprived the colony of numerous active managers, and production was suffering from it. Inflation was unbridled. To this would soon be added a drought that would cause a serious food shortage. March 1945 was also the time of the foundation of the Arab League. Minds were worked up, and everyone was outdoing the others in verbal violence. Ferhat Abbas travelled throughout the country, spreading his spirit of “ resistance ”, on the model of what was happening in metropolitan France, while Messali gave his orders through press communiqués.

Let us return to Algeria, where the economic situation was worsening from day to day. Mobilisation on the one hand, the purge on the other had deprived the colony of numerous active managers, and production was suffering from it. Inflation was unbridled. To this would soon be added a drought that would cause a serious food shortage. March 1945 was also the time of the foundation of the Arab League. Minds were worked up, and everyone was outdoing the others in verbal violence. Ferhat Abbas travelled throughout the country, spreading his spirit of “ resistance ”, on the model of what was happening in metropolitan France, while Messali gave his orders through press communiqués.

The announcement in mid-April of the opening of a conference in San Francisco where the United Nations Organisation was to be created, spread among the natives, and the rumour went about that independence would soon be granted to them by the “ Organisation ”. The colonists in Constantine were particularly worried about how agitated people were in their region.

Now, no Prefect, no Governor General heeded these warnings. May 1st was a sort of dress rehearsal. Seditious flags and banners were unfurled in the cities. Clashes with the police ended in a death in Bone, another in Oran and two in Algiers. Mass arrests took place, but it was too late. On May 8, the drama broke out.

SÉTIF : MAY 8, 1945

On that day throughout Algeria the victory of the Allies was being celebrated. But at Sétif, Ferhat Abbas’ stronghold in Constantine, there was no Muslim in the official cortege. They had asked to parade separately. The prefect granted permission on condition that no seditious signs would be displayed. But everything was organised to defy the ban. The green standard of the Prophet was brandished. The policemen who supervised the demonstration insisted that the seditious placards and flags be removed and then tried to seize them. Shots were fired, and the policemen fired back. Then the native crowd rushed through the streets of the city to shouts of « Jihad! » and, overexcited by the strident shrieks of Arab women, massacred all the Europeans that they encountered.

When around noon order was re-established, thanks to the intervention of the army, twenty-nine horribly mutilated cadavers were picked up. The news of the riot spread like a wildfire in the surrounding countryside. Villages in turn were assailed by bands of fellahs hurtling down from the mountains. In total, more than a hundred thirty Europeans were massacred, including women and children.

Nevertheless, the separatist agitators had not succeeded in shaking the native masses, among whom the very idea of an « independent Algerian nation » remained absolutely alien. And a very encouraging thing was that not one native soldier rebelled; all their units remained faithful to the French authorities and greatly contributed to re-establishing order.

General Duval, who commanded the division in Constantine, only disposed of limited means. Consequently, to quell the rebellion, he had to act quickly and strike hard. The soldiers who were sent to the besieged villages dispersed the insurgents with machine guns. On the evening of May 12, the insurrection had been repressed.

On May 30, when the operations were finished, General Duval wrote his report to the government: « I have given you peace for ten years, but you must not delude yourselves. All must be changed in Algeria. Serious reforms must be made. »

SORROWFUL CONSEQUENCES

The Sétif insurrection would subsequently be considered a prelude to the War of Algeria, the first event that widened the “ gap ” between the two communities. Undeniably the matter was serious and the traumatism profound, both among the natives and the Europeans. In order to re-establish order, it was necessary to act with severity, but after the show of force, there was need to hasten to take charge once again of the populations that were temporarily led astray, to restore the “ colonial bond ” that was too slack, in these regions of eastern Algeria, particularly the Aures. Unfortunately nothing was done…

Other than to drag the army’s name through the mud by accusing it of not giving quarter. The army estimated at 1300 the number of native victims. But the American consul in Algiers spoke of 50,000 deaths, a lie that would later on be repeated by the FLN.

Both in Paris and Algiers, the drama was forgotten, as were General Duval’s warnings also. The National Assembly voted an amnesty for the rebels. Ferhat Abbas, the pharmacist from Sétif, and his lieutenants were liberated in March 1946 and came back to the country more arrogant than ever. Messali Hadj, who was liberated somewhat later, founded in October 1946 a new party: the Mouvement pour le Triomphe des Libertés Démocratiques (MTLD; Movement for the Triumph of Democratic Freedoms). Soon a wing broke off: the Organisation special (OS; Special Organisation), which advocated direct action, that is to say, resorting to arms. The OS was dismantled in 1950 after a certain Ben Bella attacked the post in Oran. Arrested and considered a simple common law criminal, he escaped in 1952. The reformed secret organisation gave rise to the “ Front de libération national ” (FLN; National Liberation Front).

THE ERA OF FAIR ALGERIA IS NO MORE

As for the French in Algeria, they saw that time was against them and that they would be sacrificed one day or another to the egalitarian myths of the parties in power in France. As for the so-called “ advanced ” Muslims, they were disappointed to receive for the time being only secondary advantages. Electoral agitation started up again with renewed vigour, against a background of religious war.

Jacques Perret saw its devastating effects: « The “ nationalists ” insist on the application of the law of numbers, the basis of democracy, and demand autonomy for Algeria, that is, handing power from the French minority over to the Muslim majority. This is, broadly speaking, the extremists’ programme, which, in fact, corresponds to this old obsession that still lies dormant in the hearts of the Muslims: drive out the Christian or enslave them. Whether they like it or not, the non-believing administrator, the atheist colonist, Mr. Chataigneau himself [the Governor General], or the sectarian teacher are above all else Christians. It is in vain that the demagogue puts on a burnous, builds mosques, makes Ramadan into a republican holiday (!); he is wasting his time and losing face. Furthermore, the Muslim (allowing for very rare exceptions) can live fifteen years in Paris, earn university degrees, drink wine, eat pork, marry a French woman and discuss existentialism, the law of the prophet remains in him. If the force of this law does not spontaneously revive within him at the sight of the coasts of Africa, his father, his mother, the entire family will entreat him and soon succeed in reminding him of good Muslim mores. This does not mean that collaboration is impossible between the roumi and the native, nor does it mean that a Muslim cannot have esteem, confidence and friendship with a Frenchman – we have innumerable proofs – but pure and simple assimilation, this old dream that socialists inherited from the Convention and of which they are just starting to rid themselves, is a chimera which, combined with the honourable gullibility of wanting to be loved for ourselves, has never done anything but lead us astray. »

A HISTORICAL COMMUNITY TO BE SAVED

To deny that the native masses had political maturity was not to deny them the right of associating themselves in the common effort. This form of integration had already been practiced for many years, far from the agitation of politicians. France had created this admirable and complex historical reality – French Algeria – rich with a hundred and twenty years of life together.

Philippe Tripier gives a tableau vivant: « The close mixing of the two communities is a fact that is undeniable by even the most prejudiced observer; it is just as obvious as the French presence… The particulars of everyday customs show the permanence of contacts and the interweaving of practical life. Whether it was the employer with his employee, the housewife with her supplier, the farmer with his workers, an employee at a counter with a client, passers-by in the street or bus passengers, everyday relationships were marked with cordiality and affability as natural as existed among people in metropolitan France […]. That this amalgamation of civilisations and mixture of populations under sole French sovereignty proceeded so well and without major difficulties on the eve of the insurrection was Algeria’s success and fundamental originality. » (Autopsie de la guerre d’Algérie, p. 29)

No place expresses better the mixture of the two communities than the shrine of Our Lady of Africa on the hill that overlooks Algiers. Not only Catholics could be seen going there but also Muslims, who had come to pray to « Lalla Meriem », Mother of Africa, and ask Her for Her baraka, Her blessing.

Algeria at that time seemed more a French province than a colony. The national revenue per inhabitant, for example, was double that of Egypt, which nevertheless was considered one of the most developed countries of Africa. The number of hospital beds was three times more numerous than Egypt; infant mortality less than half. 25,000 km of roads and 5000 km of railways criss-crossed the territory. Farms covered ten million hectares. Entire cities had been created or developed. New villages were built throughout the territory. Important waterworks had been undertaken: eleven large dams served to irrigate 140,000 hectares. Algiers was the second largest French port, and this makes no mention that oil was discovered in the Sahara shortly before the Algerian war. This is all that is needed to prove the economic and strategic usefulness of French Algeria.

Fr. de Nantes spoke of it as a “ historical community to be saved ”.

THE CHURCH’S MISSION

Jacques Perret related the secret of one of the witnesses of the events that took place in Sétif : « In the main body of the riot, I noticed that the natives were instinctively attacking all those who were fleeing. But the ardour of the most fanatical suddenly subsided before those who stood up to them. » Our friend drew a salutary lesson: « If we decide to remain, we will have to say so without ambiguity. Once France has clearly expressed her choice and given the first signs of her determination, the mass of the natives will confirm their loyalty, the agitators will abandon the adventures into which our weakness induced them. Algeria will at last regain peace and confidence. »

Who, in those years of anguish experienced by the most lucid, could have confirmed France in her resolution to remain in Algeria in order to fulfil her colonial and missionary vocation, who else but the Church, whose mission in each troubled period was to preach to men their duty of submission to tutelary authorities and the established order, the condition for the survival of human communities. But since the « liberation » in 1944, rare were those who had the courage to recall it and to go against the current of the prevailing ideology.

A FLOURISHING CHRISTIAN COMMUNITY

In 1950, there were more than 800,000 Catholics, i.e., four-fifths of the European population, who were divided into 340 parishes, which had more than 600 churches and chapels and 800 priests. Two-thirds of the priests were secular clergy; the remainder belonged to more than 22 congregations and had been established in the three départements. Algeria had been divided into three dioceses: Algiers, Oran and Constantine. This success was due to the “ Phalange ” of holy priests, religious and nuns who had been working at their apostolate for a hundred and twenty years, but also to the zeal of Msgr. Leynaud, Archbishop of Algiers.

As the young secretary of Cardinal Lavigerie at the end of his episcopate, he had helplessly witnessed the closing of many establishments and religious communities at the time when the laws of separation of Church and State were voted. Yet it seemed that Providence had chosen him to rebuild the Church in Africa. He had caught the attention of St. Pius X, and Benedict XV appointed him Archbishop of Algiers on December 24, 1916, three weeks after the martyrdom of Fr. de Foucauld! As soon as he took possession of his diocese, he reopened the major seminary of Saint-Eugene. In 1918, he blessed the first of the sixty-three churches he would build during his episcopate (1917-1953). He also ordained 131 priests, established eight religious congregations, including the Trappists, who agreed to return and settle in the heart of the Atlas mountains, in Tibhirine… The twelfth Eucharistic Congress of Algiers, which took place from May 3 to 7, 1939, marked a high point of ardour and conversions.

On February 11, 1944, Msgr. Leynaud made the vow to build a « large, beautiful church », in honour of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, which was to be an Algerian Montmartre. Because he was convinced that the Church and the French presence were inseparable in Algeria, Msgr. Leynaud did not attack the laicism of republican institutions head-on; rather, he intended to vanquish it on the battlefield. When he died on the August 4, 1953, the majority of the Catholic faithful in Algeria remained attached to their traditional religion and associated patriotism and faith: « Catholic and French forever! »

There remained, however, the nagging question of the conversion of the Muslims to be resolved.

« THOSE IN CHARGE OF THE ARABS »

During the centennial celebrations, several voices could be heard, among others that of Canon Jules Tournier, who recalled that the religious question was the key to our sovereignty in Algeria : « If republican France does not have the great wisdom of openly and fully advocating Christianity in North Africa in order to permit missionaries to bring, with official support, the Muslim populations to the Gospel, one need not be a prophet to foretell that, in spite of the huge capital investment she has made in these lands for a century and the huge works she has accomplished; in spite of the education that she given so widely to Berber and Arab tribes; even in spite of an even more widespread French settlement, she is not assured of keeping definitely the Moroccan, Algerian and Tunisian empires. Even if she governs the African lands politically and economically, religiously speaking, Islam remains the master of the Maghreb countries. Now, in a struggle, religion is always stronger than political and material interests. » (Jules Tournier, La conquête religieuse de l’Algérie, 1930, p. 250)

It is remarkable that in his 1953 Letter for Lent, one of the last recommendations that Msgr. Leynaud made to his priests concerned Muslims: « Do not forget they form a part of the souls who are entrusted to your care … We must love them all, always be ready to help them, treat them with cordial respect, do them as much good as possible. But, it is above all through goodness and the examples of a holy life that we will at last bring about, with the help of God, the much desired union of spirits and hearts. »

But it was no longer a question of converting them… For a long time, because of governmental bans, the conversion of Muslims remained outside of the preoccupations of the diocesan clergy. It was the concern of those who were familiarly called « those in charge of the Arabs », that is to say, Cardinal Lavigerie’s White Fathers and Sisters. Now, at the time that we are referring to, they themselves had abandoned the idea.

AN ANTI-AUTHORITY MINORITY

If the immense majority of the Algerian clergy adhered to the traditional Catholicism of their shepherd, a silent opposition was maturing in the dark. Fr. Scotto, the parish priest of Birmandreïs before becoming that of Hussein-Dey in the suburb of Algiers, was connected with Professor André Mandouze as soon as he was appointed to the University of Algiers in 1946. The former editor of Témoignage chrétien brought from metropolitan France the chimeras of Democratic-Christian progressivism, which he made every effort to spread in Algerian Catholic Action movements that were already contaminated by the spirit of the “ Liberation ”.

From February 1954 on, this extremely minority progressivist intelligentsia found in the person of the new Archbishop of Algiers, Msgr. Duval, a powerful protector. He was « a disastrous choice for the Christians of Algeria that would lead to a dramatic break. The fundamentally metropolitan prelate and former director of the Seminary of Chambery had made lengthy theological studies in Rome. He lacked affinity with the Mediterranean mentality and appreciable contact with the people of whom he became the religious leader; he did not touch hearts and was looked on as a foreigner. Furthermore, seven years of episcopate in Constantine had seen him become engaged in relations with reformist ulemas. » (Pierre Goinard, L’œuvre française en Algérie, p. 307)

These « engaged Christians », who will soon be found alongside the fellaghas, had taken the figure of Fr. de Foucauld for their emblem.

A DOUBLE INFIDELITY

Near the oasis of El Abiodh Sidi Cheikh in the desert of South Oran, the first Little Brothers of Jesus settled in 1933. They were founded by Fr. Viollaume « in the spirit of Fr. de Foucauld ». Their fraternity was established in a former military fort, near the tomb of a founder of a Muslim confraternity. This exclusion of the presence of the French military – or at least no one spoke of it – and this proximity with the Muslims was quite symbolic...

Near the oasis of El Abiodh Sidi Cheikh in the desert of South Oran, the first Little Brothers of Jesus settled in 1933. They were founded by Fr. Viollaume « in the spirit of Fr. de Foucauld ». Their fraternity was established in a former military fort, near the tomb of a founder of a Muslim confraternity. This exclusion of the presence of the French military – or at least no one spoke of it – and this proximity with the Muslims was quite symbolic...

Without military or political support, but also without an objective! the Brothers, soon joined by Sisters, were there for the Blessed Sacrament to silently radiate silently, as Fr. de Foucauld desired. It was very pure mysticism, « or else it manifested their desire to speak no longer of the conversion of the natives and to act as though the Eucharist, the Sacred Heart, could radiate the love of Jesus without displacing anything, without offending anyone, without changing anything except making Muslims better Muslims? » Fr. de Nantes asked. (Jesus, Master of the impossible, Community retreat, 1976).

It was already a double infidelity to Fr. de Foucauld : first they denied his dear « Saharan friendships », which impelled him to write on April 16, 1915: « The tribes make progress in proportion to the contact that they have with officers… We only do good work with officers and with good officers. »

The second denial was to pass over or silence Fr. de Foucauld’s ardent desire to convert the Muslims, his untiring devotion for the divine Host who was preparing the salvation of these poor souls plunged in darkness. « You want to know if I am in contact with the Muslims, he wrote even at the time when he was a Trappist monk to his cousin Louis de Foucauld. The conversion of these peoples depends on God, on themselves and on us Christians. God always grants grace abundantly, they are free to receive or not to receive the Faith: preaching in Muslim countries is difficult, but missionaries in so many past centuries overcame many other difficulties; it is for us to act as they did, for us to be successors of the first Apostles, of the first Evangelists. The word is a great deal, but example, love, and prayer are a thousand times better. Let us give the example of a perfect life, of a superior and divine life; let us love them with this almighty love that makes itself loved, let us pray for them with a heart warm enough to attract a superabundance of graces from God for them, and infallibly we will convert them… » (Unpublished letter, November 28, 1894)

A further degree in the deformation of the message of the apostle of the Tuareg was to pass from this state of pure mysticism to the state of « incarnation », but in a completely different universe than that desired by the Father. After the war and during the Liberation the Little Sisters of Jesus whom Sr. Magdeleine founded, put on this leftist air of mysticism. It was marked by a so-called “ missionary ” attitude, which was in fact revolutionary. They did the opposite of what monastic tradition established, but continued to claim that they adhered to Fr. de Foucauld. Fr. Voillaume’s “ monks “ followed them and abandoned their cloister in El Abiodh Sidi Cheikh to become worker priests. They no longer had anything monastic, but it was their new way of incarnating themselves « in the heart of the masses » (René Voillaume, 1954). Louis Massignon, the alleged spiritual heir of Fr. de Foucauld, Jacques Maritain, and in Rome Giovanni Battista Montini, stood surety for this transformation of the Church of France in 1945-1946, which was a presage to all the revolutionary decisions made at the Second Vatican Council.

For them, and unfortunately for the Vatican authorities themselves, it was necessary to rid themselves of the obstacle presented by the French colonies and military. Soon their mysticism of « universal brotherhood » will become the cover for a pure and simple Marxist revolutionary ideology, in contradiction with Roman Catholic order and with true Christian charity.

What a betrayal of the spirit of Fr. de Foucauld, the true “ universal brother ”, who indeed conceived his mission as distinct from that of the soldier, but also as its extension. His most cherished desire was « that the Maghreb belong to Jesus », and he new that to achieve this it was necessary « that it soon belong to France ». This is why our Father engaged himself with all his soul and all his heart, as a true disciple of Fr. de Foucauld, in the combat for French Algeria.

Brother Matthew of Saint Joseph