THE ALGERIAN WAR

6. THE STRONG NATIONAL REACTION

ON MAY 13, 1958

THE combat that the French army saw during 1957, which was called the « year of the recovery », was not limited to the Battle of Algiers but was also waged in the bled. The fire of rebellion had now reached the whole of Algeria and was fed by the international propaganda of the FLN (Front de libération nationale [National Liberation Front]) and the equipment supplies brought from Morocco and Tunisia. Since Dehiles Slimane, leader of Wilaya IV that covered the entire region of Algiers, had declared : « The paratroopers can put on a bold front in Algiers, but let them come to the Djebel to cross swords with the regular members of the ALN (Armée de Libération Nationale [National Liberation Army] and I will make them sing another tune ». Colonel Bigard took up the challenge.

On May 23, 1957, Operation Agounenda took place south of Algiers between Blida and Médéa. A large band of fellagha had massacred a captain and fifteen tirailleurs from the 5th BTA. « Now, if I were Si Lakdar or Azzedine, what would I do ? The colonel of the 3rd RPC wondered. I would dash to the west, with a thirty-hour lead… » The rebels were, in fact, heading in this direction. Bigeard launched his regiment on the scene of the action. They disappeared into the night in single file, as silent as a troop of felleghas.

The operation used exemplary tactics; the outcome was that ninety-six rebels were killed and twelve taken prisoner. The 3rd RPC counted eight dead and twenty-nine wounded.

But the leaders of the ALN then abandoned their pretension of being able to confront the French Army in full force. Their type of tactics from then on would be acts of sabotage and aggression, ambush, and treacherous attacks were followed as quickly as possible by breaking off the action.

THE ARMY BETWEEN WAR AND PEACE

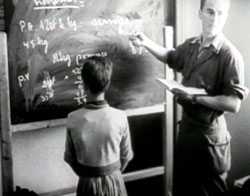

The missions entrusted to the army continued to increase. To proper military tasks others were added that would have ordinarily fallen within the competence of the civilian sector if it had had the means to carry them out : administration, public instruction, medical assistance, public works, professional training for the youth, census taking, traffic control, etc. This is without even mentioning protection and technical help given for exploiting the Hassi R’Mel gas deposits and the Hassi Messaoud oilfields that were discovered in June, 1956 (See the map).

« It is quite certain that the priority was to free the population from the hold of the FLN, General Allard explained, to tear off the veil of fear that was paralysing it and then, and only then, would it became possible to undertake a constructive work of pacification. As soon as police and army operations had cleansed the target area, the first goal was to prevent the FLN from returning in force or from infiltrating its agents clandestinely by maintaining a sufficiently dense presence there. One day, an SAS (Specialised Administrative Section) settles amidst the population. It is not a question of distributing subsidies, which would be seen as alms, but of creating useful work for the community. For instance, it could be a watering place, then a trail. In this way, these works earn salaries that improve living conditions. […] In the same way, free medical assistance was organised. The ice was broken, suspicion tended to disappear. […] All this formed the first step towards pacification. The population did not yet dare to commit itself; it watched and waited. They could hardly believe it. Was all the FLN propaganda nothing but lies ? Then a former sergeant called out to the officer : “ Give us weapons; we will defend ourselves against these bandits ! ” It was in this way that village self-defence groups were born. A new stage was reached. The engagement of the population was well underway. […] » 1

« It is quite certain that the priority was to free the population from the hold of the FLN, General Allard explained, to tear off the veil of fear that was paralysing it and then, and only then, would it became possible to undertake a constructive work of pacification. As soon as police and army operations had cleansed the target area, the first goal was to prevent the FLN from returning in force or from infiltrating its agents clandestinely by maintaining a sufficiently dense presence there. One day, an SAS (Specialised Administrative Section) settles amidst the population. It is not a question of distributing subsidies, which would be seen as alms, but of creating useful work for the community. For instance, it could be a watering place, then a trail. In this way, these works earn salaries that improve living conditions. […] In the same way, free medical assistance was organised. The ice was broken, suspicion tended to disappear. […] All this formed the first step towards pacification. The population did not yet dare to commit itself; it watched and waited. They could hardly believe it. Was all the FLN propaganda nothing but lies ? Then a former sergeant called out to the officer : “ Give us weapons; we will defend ourselves against these bandits ! ” It was in this way that village self-defence groups were born. A new stage was reached. The engagement of the population was well underway. […] » 1

We could multiply examples of this far-reaching action of the French Army. The more visible result was the increase in the number of harkis 2, back-up soldiers who had chosen to serve France. They were organised into self-defence groups or they formed mobile units that operated in liaison with our regiments or insured the protection of the SAS. In 1956, there were 2,000 of them and at the end of 1957, there were 30,000. At the same time, the number of schools increased from 57 with 2,000 pupils to 376 with 24,970 pupils. 2,300 km of new roads and trails were opened, 720,000 medical consultations and 5,000 surgical operations carried out.

We could multiply examples of this far-reaching action of the French Army. The more visible result was the increase in the number of harkis 2, back-up soldiers who had chosen to serve France. They were organised into self-defence groups or they formed mobile units that operated in liaison with our regiments or insured the protection of the SAS. In 1956, there were 2,000 of them and at the end of 1957, there were 30,000. At the same time, the number of schools increased from 57 with 2,000 pupils to 376 with 24,970 pupils. 2,300 km of new roads and trails were opened, 720,000 medical consultations and 5,000 surgical operations carried out.

THE FLN EXTENDS ITS HOLD IN FRANCE

The failure of the FLN on Algerian territory was only a matter of time. The only solution left was to find money and men outside the country. In 1957 and 1958, the FLN intensively developed its activities in metropolitan France, insuring itself an exclusive predominance over the 330,000 expatriated Muslim workers, who were concentrated in Marseille, Paris and the North. Fund-raisers collected a tax from the Algerians even as death squads executed sentences handed down by the leaders against pro-France or recalcitrant personalities.

Very rapidly, the FLN extended its hold over almost 90 % of the Algerian colony. Its shock groups used weapons of war that for the most part came from the stocks of the Resistance that the French Communist Party had held onto. For their part, Communists and progressivist Christians organised demonstrations against sending the contingent, hid agents wanted by the police or organised networks to allow young expatriate workers to reach training camps in Tunisia.

BARRICADES AT THE BORDERS

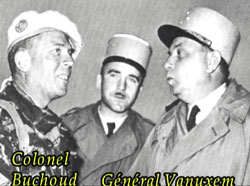

To prevent these ALN soldiers, once they were trained and armed, from penetrating into Algerian territory and supplying the interior underground, the French army decided to set up barricades at the borders. The initiative was taken locally by marines on the Moroccan side at the beginning of 1957. On the Tunisian side, the barricades started to be effective in June of that same year (See the map). Salan set General Vanuxem the task of defending the eastern roadblocks. From his HQ in Bône, he understood that the outcome of the war would depend on what would take place at the borders. He got paratroopers and the Legion to be sent to the scene of the action. His pragmatism did not trouble itself with formalities. Disregarding the administrative cumbersomeness, he sent his shock troop colonels, Buchoud and Jeanpierre, and put at their disposal infantry troops, armoured vehicles, helicopters, air forces, etc.

To prevent these ALN soldiers, once they were trained and armed, from penetrating into Algerian territory and supplying the interior underground, the French army decided to set up barricades at the borders. The initiative was taken locally by marines on the Moroccan side at the beginning of 1957. On the Tunisian side, the barricades started to be effective in June of that same year (See the map). Salan set General Vanuxem the task of defending the eastern roadblocks. From his HQ in Bône, he understood that the outcome of the war would depend on what would take place at the borders. He got paratroopers and the Legion to be sent to the scene of the action. His pragmatism did not trouble itself with formalities. Disregarding the administrative cumbersomeness, he sent his shock troop colonels, Buchoud and Jeanpierre, and put at their disposal infantry troops, armoured vehicles, helicopters, air forces, etc.

What is called « the Battle of the Borders » lasted more than three months, from the end of January to the beginning of May 1958. This mission was extremely trying for the soldiers, due to the endless night watches when the patrols were constantly on the alert and had to fight in the suffocating dust of the sand. The scenario became a ritual. The ALN forces would attempt to force the barricades. It was formed of two parallel networks, crossed by a railway, each one including a four-meter width of barbed wire, an electric fence and a hedge made of sloping panels. When armoured vehicles on patrol on the trails located the break reported by the interruption of the network, the alert was given and battle stations was sounded to awaken the camps...

After two months, the moudjahidin were terrorised at the simple prospect of having to cross this barricade. In the Tunisian camps, there were acts of insubordination, and the leaders had to be ruthless in order to launch further waves of assault.

The victory of Souk Ahras marked the end of the Battle of the Borders. The ALN left 4,000 dead, 600 prisoners and 3,300 weapons seized. The French had also paid a heavy price : 279 dead and 758 wounded. The sacrifice of these brave men had not been useless, since the aim of the battle was to choke the Algerian rebellion rapidly.

A POWER IN FULL DECAY

The Army’s successes in Algeria did not strengthen the determination of those in power – quite the opposite ! – and that was the scandal. As a consequence, anxiety reappeared among the French in Algeria, and an attitude of wait-and-see once again gripped the Muslim populations.

The army remained silent, and this silence was fraught with apprehension. Some base measures to economise had been ordered, such as reducing the number of soldiers, fuel allowances, packaged rations, etc. The army champed at the bit and felt as though it would once again be deprived of its victory. « Don’t let them prevent us from winning ! We want no more betrayal ! » was what was heard in the canteens.

Four months after it came to power, the Bourgès-Maunoury government fell, and France treated itself to a five-week crisis. In November 1957, the radical Félix Gaillard was at the helm. This brilliant thirty-seven year old technocrat could not find anything better for his inaugural speech than to declare that he was ready to negotiate with the rebels when they were becoming more and more provocative.

THE SAKIET PUT-UP JOB

In January 1958, a platoon and a commando group from the 23rd Infantry Regiment on patrol along the Tunisian border fell into an ambush close to the border post of Sakiet-Sidi-Youssef (See the map). The operation had been orchestrated with the obvious complicity of the Tunisian National Guard. After a purely pro forma protest, the French government did nothing to punish the affront, avenge the memory of the dead and attempt to recover the prisoners. This time, the army itself took the imperative decision and, in the name of the « right of pursuit », which had been accepted in a previous Cabinet meeting, a B-26 squadron bombarded the village where the firing had originated.

But it was a ruse. The ALN had purposely invited a team of the International Red Cross on that day in order to be witness to the « French aggression ». Needless to say, the French left-wing were the first to flare up against the army.

To reap the benefits, the FLN then put pressure on Bourguiba, the Tunisian president, to have him submit the matter to the UN Security Council. As could be expected, the United States and Great Britain hastened to offer their arbitration. That was not without ulterior motives. In November 1957, these two countries had decided to supply weapons to Tunisia. It was obvious that the Algerian rebellion would benefit from them. Robert Murphy, the former American consul to Algiers, was sent to Paris. Under the blackmail of an interruption of American financial assistance to France, the French Cabinet accepted the “ good offices ” of the Anglo-Saxons. Would the FLN regain at the UN what it had lost on the terrain ?

All this politico-diplomatic tumult lacked discretion. Shame and anger increased in the country; the parliamentarians refused a vote of confidence to Félix Gaillard, whose government fell on the April 15. Immediately, negotiations between the parties resumed, but this time there seemed to be no solution to the crisis. Without knowing it, one was witnessing the last convulsions of the fourth Republic.

UNDER THE SIGN OF JOAN OF ARC

On April 26, ten thousand war veterans and supporters of French Algeria gathered for a silent march and demanded the establishment of a government of national security. On that day, ten thousand hands were raised to affirm : « in the face of all opposition, on our graves and our cribs, before the memory those who died on the field of honour, we swear to live and die French in the land of Algeria, forever French ».

On April 26, ten thousand war veterans and supporters of French Algeria gathered for a silent march and demanded the establishment of a government of national security. On that day, ten thousand hands were raised to affirm : « in the face of all opposition, on our graves and our cribs, before the memory those who died on the field of honour, we swear to live and die French in the land of Algeria, forever French ».

The last straw came on May 9 when the Tunis radio announced the execution of three French soldiers by the FLN. What response did the French government make to this provocation ? None. First, there no longer was a French government. Félix Gaillard merely disposed of day-to-day matters. The French in Algeria were exasperated by this impotence. The resident general minister, Robert Lacoste, sensed it and, far from facing the situation, chose to return to metropolitan France. A demonstration in honour of the three executed soldiers was organised for May 13.

The previous day, Sunday, May 12, Algeria celebrated, in union with the home country, the national feast of St. Joan of Arc. The edition of the journal L’écho d’Oran headlined : « Oran has paid a moving tribute to the patron Saint of the country ». At the end, one could read : « last minute news : Political tension is increasing in Algiers. Patriotic associations and national parties call for a general strike tomorrow afternoon. »

Among these pied-noir associations, the one composed of the friends of Robert Martel (see insert below) was perhaps the most determined. On the evening of May 12, their leader announced his decision : the following day, the general Government would be besieged. Then what ? Then, they would call in the army. Then what ? The French army would be able to impose a government of national security. « The crowds would follow », he claimed. Dismissed at first, the idea took hold, and May 13 dawned, a May 13 that would mark Algerian and French history.

THE CHOUAN FROM THE MITIDJA

IT is through his reading of Robert Martel’s book “ La contre-révolution en Algérie ” (Diffusion de la pensée française, 1972) that our Father understood how much May 13, 1958 was « something providential, as human as it was divine ».

Born in Algiers in 1921, Robert Martel was a viticulturist in the plain of the Mitidja. He was father of three children and had simple and clear ideas about everything; the events proved how very sound they were. On top of that, he was a born leader but at the last moment of the fight he preferred to withdraw rather than to impose himself.

Born in Algiers in 1921, Robert Martel was a viticulturist in the plain of the Mitidja. He was father of three children and had simple and clear ideas about everything; the events proved how very sound they were. On top of that, he was a born leader but at the last moment of the fight he preferred to withdraw rather than to impose himself.

Completely allergic to racism, he liked Muslims, this little world of farm workers with whom he rubbed shoulders every day in his village of Chebli or who worked with him on his lands. As a staunch supporter of this « historical community », he would do everything in his power to save it. An almost innate reflex would allow him to spot any racist provocation. One day he heard that one of his men wanted to leave a charge of plastic explosives at the shop of a native greengrocer who had been convicted of helping the FLN. He grabbed the man and dragged him to a crucifix : « He did not ask you to do that », he told him. His great love had been Fr. de Foucauld ever since he was in the Saharan Companies during the war.

With no class bias, he had bold social ideas, like the development of rural schools intended to give required qualifications to the prolific Arab labour force. He even spoke of “ agrarian reform ”. No ambition or electoral temptation could be detected in him. Anxiety for the country, for Algeria as well as for France, alone haunted him. On the day that Dien Bien Phu fell, he wept, thinking that it would soon be Algeria’s turn to be grappling with Communist subversion. Thus Bloody All Saints Day in 1954 found him determined : « I have been shouting it from the rooftops, but no one wants to listen to me. The Indochinese war is beginning again. Do you understand ? – all Africa is going to bear the brunt. France has never respected the effort of her own in the colonies. The Republic ruined everything… But if necessary, I will lose my life at it; it will not be said that I did nothing to try to save my province. »

For him, the evil was the French Revolution, the democratic institutions that it fathered, and the deceitful motto Liberty-Equality-Fraternity that deceptively covers a heap of acts of injustice and hatred. He was called « the chouan from the Mitidja ».

With his colonist neighbours, Martel began by creating the first village militia in his village of Chebli. Then, with a few trustworthy friends he established on August 25, 1955 the French North African Union [Union française nord-africaine (U.F.N.A.)]. It was a question of warning his compatriots of the danger that threatened them, and which few of them at that time had gotten the measure of. It was an ungrateful mission if ever there was one. Getting nothing but rebuffs, he turned to Fr. de Foucauld with very simple words :

« It is impossible that you did all that for nothing. Since God exists, prove it to us; save Algeria. I place myself at your disposition, I accept your orders, but give me the means to fight. From now on I promise to invoke you every evening, as long as there is a breath of life in me. In advance I accept all. »

People of good will began to flock, and funds flooded in. The movement increased in scale and was soon able to cover the entire province. This covering was not a conception tacked onto a reality in a Marxist manner : « It was based, Martel wrote, on chains of friendship, on natural, living networks, often grouped around professional associations, and had no other goal than to prevent subversion from establishing itself in villages and in the countryside, to avoid blind attacks or racist attacks, to cement the age-old alliance of the French and Muslim communities. »

At that time, all sorts of vain projects were being formed, uselessly dissipating good will. But Martel managed his affairs well. There were also deceptively reactionary, rival movements that received money from the big colonists or the government. The U.F.N.A. was absolutely pure of any dishonest compromise. This allowed it to perform master strokes successfully : on February 6, 1956, the tomatoes thrown in the face of Guy Mollet to prevent the appointment of Catroux as Governor General was the work of Martel ! When the C.R.S. (Police) answered tomatoes with tear gas, Robert was in the front line to take the blows… He had but one word to say : seven hundred friends were gathered not far from the Forum, with weapons and ready to use them ! The tomatoes had produced their effect on Mollet, who withdrew Catroux’s appointment. Martel gave the order to disperse his troops. The trial of strength had not yet come.

Lacoste was designated to succeed Soustelle and continued the same policy; Martel was wary of these left-wing politicians, who remained Socialist and Freemason under a reactionary exterior. Thus he was furious to see the people of Algiers acclaim all those who, like Soustelle, used French Algeria as an electoral springboard.

After the dissolution of U.F.N.A. by Lacoste, Robert Martel created the French Renaissance Centre [Centre de Renaissance française (C.R.F.)], which he organised and directed masterfully. If he refused all dishonest compromise with politicians, he was wary as well of activists who wanted to pay back the Muslims for all the FLN’s acts of terrorism. « You are playing into the hands of the adversary, he told them. In reality, legitimate defence must materialise against the State that no longer defends us. It is against it that we must defend ourselves and against it that we must rise up. Nevertheless, we must have the means to do so. » He had understood that it was necessary « to strike at the head », that is, to overthrow the Republic.

He saw General de Gaulle’s return, however, looming on the political horizon. « No one is Gaullist in Algeria. You see, Jean, he said to his friend Crespin, if the Army shouts, " Long live de Gaulle ”, and has people shout it out, we have had it. » For three years he sought to arouse popular, counter-revolutionary fervour for the defence of French Algeria, and saw very well how the Regime defended itself. This time the… Would he be able to thwart it ?

THE PROFOUND MOTIVATION BEHIND MAY 13

In his book, “ Réquisitoire contre le mensonge ” (the Gaullist lie !), René Rieunier distinguishes five determining factors in the uprising of May 13, 1958 : the popular consent that prompted it, the action of the “ phalanx of nationalists ” that was its mainspring, the manoeuvres of the Gaullist clique to channel the uprising, General de Gaulle’s subtle game, and lastly, the role of the army, which was decisive.

1° Most of the pieds-noirs would stop at nothing to save their land and family, and although metropolitan France did not experience as intensely the tragedy that assailed Algeria, it could no longer tolerate the political system that displayed its incoherence and corruption at each crisis.

For his part, Fr. de Nantes wrote : « The coup in Algiers came from the people who sought to save the country. It was the reaction to anarchy, which cannot help but break out when soldiers are killed without reason, while the government no longer even reacts to insults from abroad nor to interior betrayals; when peaceful citizens are despoiled, exiled, tortured without this rousing the slightest feeling of pity among their parliamentary representatives; finally when the country is thrown, bit by bit, to the covetousness of foreigners and to the ambitions of the worst, all this in the very name of the idea that presides over the Constitution : Democracy. » 3

2° In metropolitan France, the nationalists were wiped out by the purge of the liberation in 1944. But their phalanx re-emerged in the ardent land of Algeria. There were Robert Martel and his colonist friends, who openly led their conspiracy under the sign of the Heart and Cross of Fr. de Foucauld; there were Pierre Lagaillarde and his students from the University of Algiers : the son of a left-wing lawyer converted to nationalism, he claimd that he was ready to die on the barricades; and lastly, doctor Lefèvre, a father of seven children, a zealous corporatist and admirer of Marshal Pétain, Franco and Salazar. « Here were three men, Rieunier wrote, behind whom not only the Europeans of Algiers but a large number of Muslim would fall into line on May 13. These were the authentic apostles of French Algeria. They had no ambition for themselves, but they wanted to show France and her army that they preferred to die rather than to abandon Algeria to the rebellion, where it would become the prey of Communism. »

3° The third factor was the Gaullist clique, composed of idealists, ambitious persons and political racketeers. Some of them were enthusiastic, generous and full of illusions about their mythic “ Leader ”; the others, the close entourage, banked on him for more pragmatic reasons : honours, money and business. Their clear advantage was that they had a name to propose to the crowd and to the army. They sensed that the regime was tottering, that the Republic was threatened. According to them, De Gaulle would be the saviour of the Republic. The Gaullist plot was organised in 1957. In the Félix Gaillard government, Chaban-Delmas, who was whole-heartedly Gaullist, was Minister of National Defence. He sent Léon Delbecque, a sort of fideicommissum, to Algiers with the mission of creating an information source. This Delbecque was a friend of Soustelle...

4° Their great man was an isolated man, without any affiliation, with no other link to the nation than the pretension of having liberated it. General de Gaulle had no account to give but to himself and to the « certain idea » he had about France. He had left politics twelve years earlier.

« Lurking in the darkness of Colombey, Dominique Venner wrote, the General marked time, letting the situation decay, which could but serve him, the last resort. ” 4

5° The Army was, however, the true arbitrator of the situation. Its last operations in the djebel and on the borders had been crowned with success. It was commanded by officers of great merit, who for the most part had fought in Indochina. The populations there had become attached to them when they had sworn to protect them, to remain with them. When they had to betray their oath and abandon them to the Communist hell, these officers said to themselves : « Never again will we accept such a shame. » To the terrorised Algerian natives who begged them : « Hey, lieutenant, promise us that you will not leave ! », they swore that they would remain. An oath made in the name of France ! They would do all they could to keep it.

Nevertheless, if the Army kept a watchful eye on the movements of the Algerian masses, it did not make plots. When power fell into its hands, it did not know what to do with it and hastened to relinquish it because it lacked a political doctrine. We have seen how in 1944 it had been purged and forced to deny its most prestigious leaders : Marshal Pétain, who had the stature of a statesman 5. The war in Indochina had partially healed the wounds and restored its unity, but most of the leaders of 1958 had started their military career in the Resistance or in the ranks of Free France. From such beginnings they retained a blind commitment to the one who, according to them, embodied the “ myth of the Resistance ”, General de Gaulle. They could not imagine the betrayal of which he was capable.

« POWER TO THE ARMY »

In this morning of May 13, a strange atmosphere of an open city pervaded Algiers. The beaches were totally deserted. Few Arabs were in the streets; they observed the Europeans. At 1 pm, the appointed time for the general strike, the inhabitants of the hinterland began to arrive. Colonists came from the Mitidja and the Sahel in long car convoys with flags flapping in the wind. Leaflets thrown from planes or phone calls had informed them of the strike. The organisation of Robert Martel had operated to the maximum.

In this morning of May 13, a strange atmosphere of an open city pervaded Algiers. The beaches were totally deserted. Few Arabs were in the streets; they observed the Europeans. At 1 pm, the appointed time for the general strike, the inhabitants of the hinterland began to arrive. Colonists came from the Mitidja and the Sahel in long car convoys with flags flapping in the wind. Leaflets thrown from planes or phone calls had informed them of the strike. The organisation of Robert Martel had operated to the maximum.

The field day crowd of 50,000 to 80,000 persons had gathered around the war memorial on Laferrière Boulevard on the Glières Plateau. Martel soon joined them with his flag on which were inscribed the three words : Honour, Willpower, Homeland. He was accompanied by Lagaillarde in combat dress and escorted by four armed harkis. A huge clamour welcomed them. The absence of the Gaullist group was remarked. They were convinced that the day for the coup had not yet arrived. Lagaillarde harangued the crowd, while Martel humbly remained in the background.

The field day crowd of 50,000 to 80,000 persons had gathered around the war memorial on Laferrière Boulevard on the Glières Plateau. Martel soon joined them with his flag on which were inscribed the three words : Honour, Willpower, Homeland. He was accompanied by Lagaillarde in combat dress and escorted by four armed harkis. A huge clamour welcomed them. The absence of the Gaullist group was remarked. They were convinced that the day for the coup had not yet arrived. Lagaillarde harangued the crowd, while Martel humbly remained in the background.

At 6 p.m., General Salan, accompanied by the Generals Massu and Jouhaud, and Admiral Auboyneau, commandant of the navy, arrived at the war memorial to honour the three soldiers killed by the FLN. At the same time, in all the garrisons of Algeria, a similar ceremony of “ reparation ” took place (Vanuxem). Placing a spray of flowers, a minute of silence was followed by a thundering Marseillaise. A cry burst forth : « Power to the army ! ». Yet the generals, whose faces were grave and tense, withdrew without saying a word. The moment had come. Robert Martel hesitated for a moment; his eyes met those of Lagaillarde, who cried out the watchword : « Everyone to the General Government against the corrupt regime ! » The two men walked side by side to the Forum with a calm and determined step, followed by the crowd.

The Forum was this vast esplanade between the sky, the sea and the gardens that dominate the Glières Plateau. On the right side stood a gigantic parallelepiped : the General Government, a symbol of the central power in Paris that was betraying Algeria.

THE TAKEOVER OF THE GENERAL GOVERNMENT

A rioter drove a vehicle through the gate. Then, there was a scramble. The overexcited crowd rushed into the big building like water into the ripped open hull of a boat. The demonstrators poured into the offices and threw everything they could lay their hands on out the windows : folders, circulars… The chaos was phenomenal. The statue of Marianne 6 disappeared in the mêlée, a waste basket on its head.

Lagaillarde and Martel were very determined to maintain the pressure to force the army to take power. At this precise moment, Massu arrived with a crew cut, and his peremptory and cheeky language. His first job was to throw out all those who had no reason to be in the General Government building. In the meanwhile, the people outside were proclaiming their determination. Salan arrived in turn, stiff, inscrutable. As the commander-in-chief, it was he who was supposed to embody legality and republican order. As the insurgents demand that a Committee of National Security be set up, Salan appointed Massu to be the chairman.

The latter then sent the following telegram to President Coty : « Report to you creation of a civil and military Committee of National Security in Algiers. Due to the seriousness of the situation and faced with the absolute necessity of maintaining law and order to avoid bloodshed, the Committee vigilantly awaiting the creation in Paris of a government of public security, alone capable of keeping Algeria as an integral part of metropolitan France ». When he read it to the crowd, Massu, who was a Gaullist, came out with the fatal word : « a government of public security presided over by… General de Gaulle. »

He had not been the only one to say it. Delbecque, who was “ a boor ” according to Salan, arrived in the meantime at the General Government, with Lucien Neuwirth. As they had been caught off their guard, they had to make up for the lost time. They were clever enough to present themselves as envoys of Soustelle, and the mere name of the former general resident of Algiers was enough to open all doors, beginning with that of the Committee of National Security. It took no time for Delbecque to have himself appointed vice-president ! A few moments after Massu’s telegram, he went on his own initiative to announce to the throng still massed on the Forum that Soustelle’s arrival was imminent. There was a thunderous applause. It was a lie, but lying is the Gaullist weapon par excellence !

During the night, it was learned that the National Assembly had granted its investiture to the government of Pierre Pfimlin, with the mission of finding a solution to the Algerian crisis. In what sense, we know only too well : Pfimlin, an MRP deputy from Alsace, declared that he would seize « all occasions to undertake negotiations [with the FLN !] and to call on the good offices of the Tunisians and Moroccans ».

Before announcing the news to the crowd, Salan took care to read the following proclamation : « Inhabitants of Algiers, since I have the mission of protecting you, I am temporarily assuming the destiny of French Algeria. I ask you to have confidence in the Army and its leaders, and to manifest your calm and determination. » The speech of the commander-in-chief was greeted with a long ovation. It was 4 a.m. The happy throng dispersed. An officer let out : « Oh ! After all, there are no deaths. Except for the Republic, and that does not matter ! »

THE MANDARIN IN THE STORM

In Oran and Constantine, the events are slower than in Algiers, but the same « spontaneous national revolution » was under way. On the other hand, in Paris, the government was panicking. The parliamentarians feared for their persons and parties.

What was Salan going to do ? Everything depended on him now. Would he remain within legality ? Would he cross the Rubicon ? The one who was called « the mandarin » remained inscrutable. As early as 10 a.m., the Forum was packed solid with people. To protest against the investiture of Pfimlin, the Committee of National Security (CSP) asked that people participate in the general strike. Enthusiastic telegrams began to flow in from all the villages of Algeria and from the Saharan posts. The Territorial Units (mobilised civilians) joined the demonstrators. The paratroopers maintained good order. Paris telephoned the commander-in-chief : « Do you have the troops under control ? – Yes, Salan replied, and he added in a firm tone : to keep Algeria French. »

As for Delbecque, he made great efforts to promote the interests of his boss. He would admit it : « I busied myself with being at the right place at the right time in order to divert towards General de Gaulle the uprising that was about to take place. » But, on the evening of this May 14, when Salan sounded out the officers of his staff : « I am told that the only solution is to have recourse to de Gaulle. Who among you is Gaullist ? » No one replied…

THE DAY OF THE DUPES

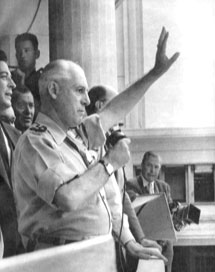

Alas ! The following day, May 15, Ascension Day, Salan began to yield. He believed that he was serving a cause, French Algeria, but in reality he put himself in the service of a man : de Gaulle. Having realised that he had gained self-confidence, the members of the csp of Algeria asked him to speak to the crowd from the balcony. Salan accepted.

« I will have you know that I am one of your number, he cried out, provoking an indescribable show of enthusiasm. My son is buried in the Clos Salembier cemetery. I am unable to forget that he rests in the land that is yours. » He ended with a vibrant : « Long live France, long live French Algeria ! » The general-in-chief had finished. He turned around to leave the balcony when Delbecque, who was behind him, whispered to him :

« I will have you know that I am one of your number, he cried out, provoking an indescribable show of enthusiasm. My son is buried in the Clos Salembier cemetery. I am unable to forget that he rests in the land that is yours. » He ended with a vibrant : « Long live France, long live French Algeria ! » The general-in-chief had finished. He turned around to leave the balcony when Delbecque, who was behind him, whispered to him :

« Shout “ Long live de Gaulle ”, General, then everything will be all right. » Salan hesitated, looked around himself, then rapidly went up to the mike and shouted :

« Long live de Gaulle ! »

« Why the deuce did he shout that ? » wondered Mrs. Salan, who called out to Delbecque from an adjoining office : « Well ! You’ve put your foot in it. » In Paris, they could not believe their ears. In Pflimlin’s entourage someone said ironically : « Incredible ! Salan is anti-Gaullist. Someone must have been holding a gun to his head. »

No ! No one was holding a gun to his head, but as our Father wrote, « someone was needed ! Maurras explained time and again that from anarchy ineluctably comes dictatorship, from Demos to Caesar ! This inorganic crowd without established organisers, without a designated elite, this crowd that had suddenly escaped from the constraint of the administration of the State, that had gathered together on the Forum of Algiers and wanted to be saved, protected, needed a name, a saviour to whom it could vow itself, immediately, without explanation, without discussion. The first name to come to them, the best known, was a legendary name, a name lastly that evokes memories of unity and national pride : de Gaulle ! de Gaulle ! DE GAULLE ! A name was shouted, repeated, it finally shook the air. The mechanism was released that would bring the man back to the summit of the State, as though taken from an idealised image, once again armed by destiny with full powers to save or damn us. » 7

When Martel heard Salan’s cry he turned pale. He leaned towards his friend Crespin : « We are done for. » After a silence, Crespin asked : « What can we do ? »

– We will have to try to limit the damage and avoid, if possible, the worst, replied the “ chouan from the Mididja ”, who was a member of the Committee of Algiers. You see, for me, May 13 is truly a miracle, and it is possible that God may once again intervene. Notwithstanding that, now that I am on the inside, I am going to attempt to stick at it and try to open the eyes of the officers. If de Gaulle comes back, it will be to liquidate French Algeria, and the army will have to rise up against him. Yet we are going to have to suffer, because there is propaganda that already presents him as the saviour. The people have forgotten all the harm this man has done to France. »

It was enough that Salan had uttered at Algiers the fatal word, which was regarded as seditious in Paris, for General de Gaulle to abandon his silence and issue his first press communiqué : « Recently, the country has made a heartfelt show of the trust it places in me to lead it as a whole to its salvation. Today in the face of the trials that once again arise against it, may it know that I hold myself ready to assume the powers of the Republic. » Here he caricatures Marshal Pétain, who was called upon each time the country was on the verge of ruin.

This May 15 was a veritable day of the dupes. It was on that day that the movement of Algiers toppled and began to work in favour of de Gaulle. But before relating this Machiavellian conquest of power, let us go back once again to the Forum where, on May 16, something extraordinary happened, something that amazed and overwhelmed to the point of tears, journalists, foreign observers, soldiers and of course the pied-noirs.

THE FRATERNISATION OF MAY 16

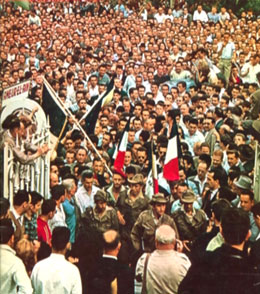

Until then, the demonstrations of May 13 and the two days that followed were the business of Europeans with, here and there, a few groups of Muslims who associated themselves with it by their acclamations. But on May 16, it was the entire Casbah where a Committee of National Security had been formed under the chairmanship of its mayor, Joseph Hattab Pacha, a Muslim convert, who arrived at the Forum in serried ranks, banners unfurled, to join the demonstrators. (…)

From the moment when the French of Algeria manifested their determination to remain French at all costs by joining forces behind their military leaders, the Muslims felt that they could show as well what they had in their hearts. They did so freely. The best auxiliaries of the Muslim community, like Captain Sirvent from the barracks of the Zouaves, had well prepared the terrain. All, however, were amazed at the rediscovered unanimity, and first among them, the FLN itself.

From the moment when the French of Algeria manifested their determination to remain French at all costs by joining forces behind their military leaders, the Muslims felt that they could show as well what they had in their hearts. They did so freely. The best auxiliaries of the Muslim community, like Captain Sirvent from the barracks of the Zouaves, had well prepared the terrain. All, however, were amazed at the rediscovered unanimity, and first among them, the FLN itself.

Thus, on the morning of May 16, the Casbah poured into the city of Algiers. They were between thirty and forty thousand Muslims who then went up to the already crowded Forum. Europeans and Muslims, more than a hundred thousand in all, were soon completely mingled. Suddenly, the immense throng formed a chain of friendship joining hands. Expressions passed from surprise to smiles. They embraced one another, tears flowed, the same words « French Algeria » were chanted, acclamations merged to acclaim France and her army. The nightmare was finished, the devils of rebellion and hatred seemed to have been exorcised...

The following day, there were a hundred thousand Muslim demonstrators who had come this time from the inner suburbs and the surrounding villages. Salan telegraphed on May 18 to Paris :

« I believe that it is my duty to underline the exceptional patriotic fervour of the crowds. Extraordinary revolution of minds taking place in the sense of a total spiritual fusion of the two communities that constitute determining factor of the situation. In Algiers as throughout the territory, irresistible movement leads Muslims to affirm publicly will to be French. »

« I believe that it is my duty to underline the exceptional patriotic fervour of the crowds. Extraordinary revolution of minds taking place in the sense of a total spiritual fusion of the two communities that constitute determining factor of the situation. In Algiers as throughout the territory, irresistible movement leads Muslims to affirm publicly will to be French. »

What a disavowal for the FLN, which had worked furiously for months and years to dissociate the two communities and for our progressivist intellectuals who formulated its theory ! On the contrary, what a reward for Robert Martel, the born defender of this « historical community to be saved » ! And what a confirmation it is of the analyses that our Father had made in the previous year ! Yes, it was possible to save French Algeria, and a great work of restoration could come from this May 13 in Algiers, under the sign of the Sacred Heart and Our Lady of Fatima !

Provided that… the Church adhere to it and bless it. But, in the person of her highest representative in the land of Algeria, she did not believe in it… Before Msgr. Duval’s persistent silence and in order to force his hand somewhat, the Committee of National Security had the text of a motion broadcast on radio and circulated in the press that asked the archbishop to bear witness « to the spectacle of the union of hearts in the province of Algeria ». Msgr. Duval merely replied that he had made multiple appeals to this end since November 1954 : « I can but rejoice at what is and will be a sign of reconciliation. » But he revealed what he really thought to Jacques Soustelle, who had come to visit him : « This is all a hoax. They are matters of psychological action. » He had likewise severely censured those who sported the Heart and the Cross, blaming them for « using religious insignia for political purposes » !

As for de Gaulle, he did not deny the fraternisation, but he intended to cash in on it.

THE CHARMER

On May 19, General de Gaulle once again abandoned his reserve, coming to Paris to hold a press conference in which he demonstrated his cunning and megalomania : « And then ? The Algerians shouted : “ Long live de Gaulle ! ” as the French instinctively do when they are immersed in anguish or carried away by hope. At that moment they give the magnificent show of an immense fraternisation that offers a psychological and moral basis to tomorrow’s agreements and arguments, an infinitely better basis than combat engagements and ambushes. Lastly they give the best proof that the French of Algeria do not want, do not want at any cost to separate themselves from metropolitan France. For one does not shout “ Long live de Gaulle ” when he is not with the nation. »

On May 19, General de Gaulle once again abandoned his reserve, coming to Paris to hold a press conference in which he demonstrated his cunning and megalomania : « And then ? The Algerians shouted : “ Long live de Gaulle ! ” as the French instinctively do when they are immersed in anguish or carried away by hope. At that moment they give the magnificent show of an immense fraternisation that offers a psychological and moral basis to tomorrow’s agreements and arguments, an infinitely better basis than combat engagements and ambushes. Lastly they give the best proof that the French of Algeria do not want, do not want at any cost to separate themselves from metropolitan France. For one does not shout “ Long live de Gaulle ” when he is not with the nation. »

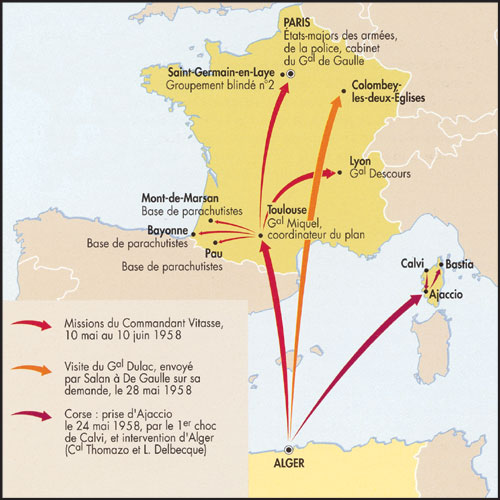

He greeted the events of Algiers as « a beginning of a resurrection » and congratulated the army for having taken over the leadership. That sufficed for it to rally. Salan addressed an enthusiastic response to him. The commander-in-chief of the troops had a secret weapon in his files : the “ Resurrection ” plan. Officers had been dispatched to metropolitan France in order to prepare the coup (two paratrooper regiments were to land in Paris), in case… There was no question of a putsch; the army did not have the intention of taking power. But the operation was intended to exert a strong pressure in order to… favour the legal investiture of General de Gaulle.

The following day, May 28, de Gaulle received at his La Boisserie estate in Colombey-les-deux-églises a mission of officers from Algeria : General Dulac, Salan’s right-hand man, and several officers involved in the “ Resurrection ” plan. De Gaulle pretended to appreciate, to consider the number of soldiers too meagre and even went so far as to say that it would be desirable that it be Salan, rather than Massu, to arrive with the first wave of the assault ! When taking leave of his visitors, he declared to them : « You will tell Salan that what he has done is well done, that it is good for France… »

For France or for de Gaulle ? Salan’s emissaries were scarcely back to Algiers when de Gaulle warned the Socialists in the government of what was brewing, that he absolutely did not support it, but that he was the only one who could prevent it. This is his refrain.

The government sent emissaries to Colombey. Politicians as well began to « stir the pot ». There was no longer anything but searching for political schemes from which everyone hoped to find self-satisfaction, but one thing was certain : de Gaulle would be their centre and the master.

On May 29, President Coty finally decided to call on General de Gaulle, « the most illustrious Frenchman », he declared, mimicking President Lebrun who in 1940 called on Marshal Pétain.

WHERE WAS DE GAULLE HEADED ?

De Gaulle had won. He triumphed not only over the left-wing opposition, but also over all those who, on the right, distrusted him. He would have no account to render to the Algerian generals and officers who worked in his favour and who would have liked to have had guarantees with regard to his future policies. To Colonel Trinquier, who in the last days of May asked Soustelle the question : « What does de Gaulle want; what solution does he envisage for Algeria ? His silence worries us », Massu replied : « Do you think that we can speak to de Gaulle like that ? De Gaulle knows what he wants to do and where he wants to go. We only have to follow him. Besides, it is a little late now to discuss it; you should have done so earlier if you had doubts. »

The “ Resurrection ” plan, which should have led to a true « national revolution », would not take place. All it did was to serve as a bogyman for General de Gaulle’s manipulation. « What I did, he declared to the Assembly on June 2, was in order for the Republic to continue ! » A few months later, Salan would say in the presence of Paillole, the former head of counter-espionage in Vichy, and of Wybolt, the head of the DST : « I wonder if we were not wrong in trusting de Gaulle and if, after May 13, I should not have sent a few paratrooper regiments to Paris. » Yes, general, this is exactly what Fr. de Nantes advocated at that time ! He declared it in July 1958 to General Miquel, the leader of the airborne troops of the south-west and mastermind of operation “ Resurrection ” :

« General, the army must put pressure on de Gaulle and prevent him from serving democracy in order to save France. »

– Father, the army is republican.

– Then, General, Algeria is lost. »

In the same month, our Father wrote an article in Amitiés françaises universitaires, to explain the equivocation of the days that had followed May 13 :

« Over there [in Algiers], the throng applauded a legendary being, the personification of the grandeur of France, and in Paris our reassured republicans saw coming back to them, borne by this tidal wave, their servant, the great tired out restorer of their democratic games ! Algiers shouted “ French Algeria ”, but acclaimed someone who still boasted over his Charter of Brazzaville, the mother of all our wars and of all our secessions. Algiers proclaimed its disgust for parliamentary government, by electing by plebiscite as its authorised representative the person who fifteen years earlier in that same city had given back to France its wretched institutions. Algiers imagined that it had found in De Gaulle the energetic leader of the real country; he was, however nothing but the baneful organiser of this legal country that betrayed us. It is a common, horrendous error, or more accurately, in the spontaneous outcry of millions of Frenchmen, it is the trace of the enormous falsehood of the Liberation. I pity this people for tomorrow, when it will fall into despair at the spectacle of the actions of its idol. For de Gaulle extended to Algeria this democratic, electoral furor, mother of all rivalries, hatreds, and deceitful promises. The strength of the Algerian movement has displanted him from his natural place, from the choice of his heart. Everything brings him back to it, enslaved to his own passions, and I fear that he will once again go to the extreme and be the best of lackeys of subversion in the name of the dignity of France. »

« Over there [in Algiers], the throng applauded a legendary being, the personification of the grandeur of France, and in Paris our reassured republicans saw coming back to them, borne by this tidal wave, their servant, the great tired out restorer of their democratic games ! Algiers shouted “ French Algeria ”, but acclaimed someone who still boasted over his Charter of Brazzaville, the mother of all our wars and of all our secessions. Algiers proclaimed its disgust for parliamentary government, by electing by plebiscite as its authorised representative the person who fifteen years earlier in that same city had given back to France its wretched institutions. Algiers imagined that it had found in De Gaulle the energetic leader of the real country; he was, however nothing but the baneful organiser of this legal country that betrayed us. It is a common, horrendous error, or more accurately, in the spontaneous outcry of millions of Frenchmen, it is the trace of the enormous falsehood of the Liberation. I pity this people for tomorrow, when it will fall into despair at the spectacle of the actions of its idol. For de Gaulle extended to Algeria this democratic, electoral furor, mother of all rivalries, hatreds, and deceitful promises. The strength of the Algerian movement has displanted him from his natural place, from the choice of his heart. Everything brings him back to it, enslaved to his own passions, and I fear that he will once again go to the extreme and be the best of lackeys of subversion in the name of the dignity of France. »

These were premonitory words, as we will see, with tears, in our next articles.

Brother Thomas of Our Lady of Perpetual Help

1. Jacques Allard, Le combat pour la paix, témoignage recueilli par François de La Morandière, “ Soldats du Djebel ”.

2. Harkis is derived from the Arabic harakat, meaning “ military movement ” or “ operation ”. Since the beginning of French colonialism in Algeria in July 1830, local people served as military auxiliaries. During the Algerian War of Independence (1954 - 1962), approximately 100,000 harkis served France in various capacities (e.g., regular French army, militia self-defence units, police, and paramilitary self-defence units).

3. Amitiés françaises universitaires, juillet 1958.

4. La grandeur et le néant, p. 219.

5. Il est ressuscité ! n° 40, p. 25.

6. Marianne, an emblem of the French revolution, is a personification of Liberty and Reason. She symbolises the “ Triumph of the Republic ”.

7. G. de Nantes, AFU, Où va de Gaulle ? juillet 1958.