THE ALGERIAN WAR

2. A FRENCH LAND (1830-1916)

FRANCE was preparing to subjugate the whole North African coast to her civilising law « in the name of the most Christian King Charles X, the Victorious » when it was learned with astonishment and consternation at Algiers on August 10, 1830 that the throne of this King had been overthrown and that the Tricouleur had replaced the White Banner.

A DISASTROUS BREAKING OF THE COVENANT

1830 unquestionably marks a « breaking of the Covenant », as Fr. de Nantes established in his “ Histoire volontaire de sainte et douce France ”. Two months earlier, Jesus Christ appeared to the humble Sr. Catherine Labouré. He was stripped of His royal garb and thus manifested that in the person of His legitimate lieutenant, it was He, the true King of France, who was losing sovereignty over His kingdom.

Algeria, the last legacy of our Most Christian Kings, would not escape the consequences of this breaking of the Covenant. At first, in order not to provide the natives with the spectacle of the deadly divisions among us, Marshal Bourmont recalled his troops from Oran and Bone, sacrificed his heartfelt convictions, had the Tricouleur raised, and handed his command over to his successor, General Cauzel. To keep Algeria for France trumped everything else.

The purge also affected religion. Thirteen of the eighteen military chaplains who accompanied the expeditionary force were repatriated on the appalling pretext that their presence would antagonise the Muslims and drive them to rebel against the French presence! The five remaining chaplains were forbidden to follow the troops on campaign. The Catholic religion was brought down to the level of Islam as one religion among all those “ practiced by the French ”.

The military conquest, the administration of the natives and even the colonisation of the lands of Algeria were marked by this scandalous State apostasy. Grace would no longer pass through the legal country, but by means of the real country, which would nonetheless accomplish God’s work, despite incredible sufferings and contradictions.

LIMITED OCCUPATION

The internal weaknesses of the usurping and poorly established government of Louis-Philippe forced it in the first months to recall three-quarters of the expeditionary force. There was even some question of abandoning Charles X’s conquest in order to please England.

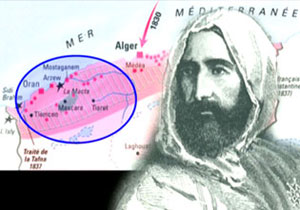

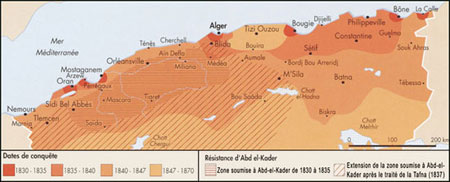

The occupation was nevertheless carried out with such pusillanimity that the rallying of the tribes that had begun under Bourmont was brought to a halt. Arab raids on our troops increased. Reprisals followed under the heavy hand of the new heads of the Army and began to resemble exterminations. We kept a few ports on the coast as trading posts for commerce, leaving the hinterland in its anarchic division among rival tribes. In the west, a young kaid, Abd al Kader, seized the opportunity and was set up as amîr al mujahîdîn (leader of the jihad) by the tribes of the West Oran region. He gave himself the mission of federating the Arabs against the French.

Another error that was fraught with consequences was that the occupation authorities never knew how to distinguish between the Kabyles, who are Berbers ethnically, and the Arabs. The former should have become our natural allies.

In the province of Oran, the Kabyle colony of Arzew sought friendship with us as early as our arrival in Algeria, and offered to provide our troops with all they needed. But the prevarications that characterised our politics made these offers useless and earned these people who had been our allies from the beginning of French colonisation only the vengeance of Abd al-Kader’s cavalrymen.

ABD AL-KADER’S REVOLT

General Trézel only had 2000 men under his orders, and when Abd al-Kader swooped down on him with his 16,000 cavalrymen on the shore of the Macta, it was a slaughter. War was declared. It was efficiently carried out by General Clauzel, who struck the emir even in his capital, Mascara, but he was unable to remain there for want of instructions and supplies.

A certain Bugeaud de La Piconnerie who did not believe in the future of our Algerian possessions was sent to Oran to sign a peace at all costs with Abd al-Kader, A generous baksheesh helped to conclude the Treaty of Tafna in May 1837.

Until such time as this treaty revealed its disastrous consequences in the west of the country, it was decided to be finished with Constantine. On October 13, 1837, the French succeeded in capturing this formidable aerie, at the end of a heroic battle in which Lamoricière won renown at the head of his zouaves.

THE NEW CHURCH OF AFRICA

In 1833, Pope Gregory XVI, enthusiastic about the French conquest, had made known his intention of giving Algeria a regular religious administration. But the government of Louis-Philippe had eluded the question several times. It was necessary to wait until August 10, 1838 in order for a Bull to restore the episcopal see of Julia Cæsarea and for Gregory XVI to name Msgr. Dupuch to it with the mission of organising the religious life of the young colony.

For three years already, the Sisters of Saint Joseph of the Apparition, under the supervision of their foundress, Mother Emilie de Vialar, whose letters bear witness to the good welcome that she and her sisters had received, devoted themselves to their new task: « The Arabs stop with admiration as they watch us treat their compatriots covered with wounds. One of them one day showed with his hand the Christ who is placed on our breast and said to me: “ He is very good, the One who makes you do these things! ” »

Mother de Vialar and her sisters were entrusted with the city hospital of Algiers, where a cholera epidemic was raging. Their devotion was boundless. Soon they were called to Bone and Constantine. An Arab leader who was cured, the foundress relates, « urged my sisters to go to Biskra, the capital of his tribes; and to the observation of one of them that the Arabs might not respect them, he replied: “ If an Arab should make the least insult to the cross that you wear, I will have his head cut off that very moment. ” »

After 1842, the Daughters of Charity provided care for the sick and also ran the local schools. The Vincentians debarked in turn, joined by the Jesuits, Trinitarians, the Sisters of Christian Doctrine, the Sisters of the Society of the Sacred Heart, etc.

After 1842, the Daughters of Charity provided care for the sick and also ran the local schools. The Vincentians debarked in turn, joined by the Jesuits, Trinitarians, the Sisters of Christian Doctrine, the Sisters of the Society of the Sacred Heart, etc.

The process of establishing a Trappist monastery at Staoueli near Algiers reveals the difficulties encountered by the clergy in Africa. The civil intendant of Algiers and the liberal deputies of the Chamber raised such obstacles to the monks’ actually taking up residence that they were forced to renounce the project.

A transaction took place as a result of which the establishment would not be considered a monastery but as a « civil society with an agricultural organisation »! The religious settled in with the help of the army at the price of incredible pains and fatigues. During the first five years ten brothers died each year. Under the leadership of a remarkable and holy abbot, Dom François Régis, the community prospered. The scrubby and arid plateau of Staoueli was transformed into a very productive model farm. On the pediment of the abbey, one can read the motto: “ Ense, Cruce, Aratro, By the Sword, the Cross and the Plough. ”

AN EIGHT-YEAR WAR

The truce with Abd al-Kader only lasted two years. At the end of October 1839, the emir again proclaimed the jihad. The reading of Parisian gazettes had informed him that France, which was consumed with interior crises, would be unable to send reinforcements in the short term.

The hostilities lasted eight years and were ruthless. Abd al-Kader and his cavalrymen first swept down on Mitidja, right to the area surrounding Algiers. They pillaged and massacred our colonists, and subjected and terrorised the hesitant native populations.

While our soldiers fell, prey more to illness and the harsh climate than to engaging the enemy, the Parisian press scoffed at their efforts. Then an orator who was thought to be hostile to Algeria took the floor; he was applying for a task appropriate to his ambition. It was Bugeaud, the signatory of the Treaty of Tafna, who now advocated total occupation by means of all-out war: « At the moment, I know no one in the higher ranks better fitted than myself for this great work. »

His proposition was accepted. He was appointed and considerable resources were put at his disposal.

As soon as he had debarked in Algeria, Bugeaud formed light and mobile columns and began to scour the country in pursuit of the elusive enemy. It was not Bugeaud, but Lamoricière, using more humane but not any less effective methods who in May 1843 allowed the tribe of Abd al-Kader to fall into the hands of the Duke of Aumale, Louis-Philippe’s son. The defeated emir took refuge in Morocco. From there, he again tried to stir up the tribes against the French. Despite Bugeaud’s victory against the Moroccan armies on the banks of the Isly River in 1844, the rebel reappeared in 1845.

As soon as he had debarked in Algeria, Bugeaud formed light and mobile columns and began to scour the country in pursuit of the elusive enemy. It was not Bugeaud, but Lamoricière, using more humane but not any less effective methods who in May 1843 allowed the tribe of Abd al-Kader to fall into the hands of the Duke of Aumale, Louis-Philippe’s son. The defeated emir took refuge in Morocco. From there, he again tried to stir up the tribes against the French. Despite Bugeaud’s victory against the Moroccan armies on the banks of the Isly River in 1844, the rebel reappeared in 1845.

Relentlessly tracked down by twenty-two French columns, Abd al-Kader was forced to surrender by Lamoricière on December 22, 1847. Was this peace at last? No, not yet. For there remained the implacable Kabylia. Bugeaud, who had mistakenly suspected that the inhabitants had hidden Abd al-Kader, mounted a punitive expedition against them. Baudicour, who was a fervent admirer of the army and sided with colonisation, was unable to refrain from waxing indignant: « The punishment exceeded the crime. The illustrious marshal was indeed able to make us feared, but he was far from making us loved. Returning from the expedition, our soldiers themselves were ashamed of the Vandal-like war that they had been forced to undertake and of the atrocities that they had committed. Thousands of fruit trees had been cut down; houses were burned; women, children and old people had been killed… »

There had never been, however, during the years of the conquest, an « organised genocide », of which “ Penitents of the colonial period ” accuse France today. Daniel Lefeuvre, a specialist on colonial Algeria has just brilliantly demonstrated this with concrete statistics: « The objective pursued by the French army was never the annihilation of the native populations but their domination. » (Pour en finir avec la repentance coloniale, Flammarion, Sept. 2006, p. 53)

THE ARMY OF AFRICA

If certain pages of the conquest were not very glorious, such as those that we have just recalled, it must be said that our establishing the “ Army of Africa ” was a success that all the other colonising peoples envied. Within the span of twenty years, France succeeded in levying a very diversified set of troops perfectly adapted to all terrains and all sorts of missions, an army not only of conquest, but of pacification. « From 1830 to the fall of the Empire, the army conquered, directed, administered and developed the country: the first French Algeria was its exclusive work. » (Pierre Goinard, Algérie, l’œuvre française, 1984, p. 87) For the most part, these soldiers were farmers or small craftsmen who were inured to hard work and cheerfully put up with it, and could make forced marches both under a blazing sun and in torrential rains, in snow or frost, always on the watch so as not to be surprised by the enemy lying in ambush.

They formed a big family, and the seven years that their enlistment lasted (!) allowed each regiment or battalion to maintain a very strong esprit de corps. Despite the absence of chaplains, they knew how to die with honour.

Zouaves, Foreign Legion, Spahis, Turkos or Algerian Tirailleurs, later on Moroccan and Senegalese, all these corps formed of native soldiers and commanded by French officers, constituted a powerful force that could bring peace, facilitate the assimilation of land and inhabitants and make them French.

A ROMAN-STYLE COLONISATION

As soon as the conquest was completed, Bugeaud, who originated from Périgord, would not rest until he had brought in colonists – by definition, a colonist is someone who cultivates the soil – by calling on demobilised soldiers. He wanted thus to develop colonies with the help of the army, that is to say, to create villages, populated with Europeans, preferably farmers. But implanting colonists could only achieve progress on condition of having the native populations share in its benefits.

The Arab Offices, established for this purpose rapidly became an essential cog of the administration of the natives. Maintaining contact with the tribes, attending to tax collection, paying auxiliaries, dealing with the natives’ complaints and appeals, such were their tasks.

As the conquest was consolidated, colonists flowed there, enticed by the flattering propaganda. Not all of the new arrivals were people deserving esteem. Lamoricière wrote regarding them in 1847: « It was on the coasts of Algeria that each class of society came to deposit its dregs. You could watch scandals and disorders unfold so very rapidly in the very heart of our colony, as a result of this monstrous agglomeration,… »

Apart from soldiers, the number of foreigners on Algerian soil exceeded that of the French. They arrived from all around the Mediterranean, mainly from Spain, Italy and Malta, but also from Germany and Switzerland. They were, for the most part, poor wretches who had come to seek fortune or simply work. They arrived without money, sometimes without agricultural experience. The army offered them a concession, and they found themselves alone to confront illness, droughts, unproductive land… Their perseverance was heroic but, after a few years, only a third remained on their concession. Yet this laborious colonisation was the one that enjoyed the most success.

Apart from soldiers, the number of foreigners on Algerian soil exceeded that of the French. They arrived from all around the Mediterranean, mainly from Spain, Italy and Malta, but also from Germany and Switzerland. They were, for the most part, poor wretches who had come to seek fortune or simply work. They arrived without money, sometimes without agricultural experience. The army offered them a concession, and they found themselves alone to confront illness, droughts, unproductive land… Their perseverance was heroic but, after a few years, only a third remained on their concession. Yet this laborious colonisation was the one that enjoyed the most success.

The main defect of Bugeaud’s colonial system consisted in the absence of a regulating paternal authority. Since everyone sought only his own profit, parties formed: natives against Europeans, soldiers against civilians. When land, Algeria’s principal asset, was to be divided, the conflict became impassioned. Clearly, the lands were poorly exploited by the natives, but the colonists always demanded more, and they accused the soldiers of checking their progress because they wanted to protect the interests of those whom they administered. On their side, the soldiers became embittered against these colonists who had come to Algeria with the lone aim of making money, while they were shedding their blood.

Who could resolve this thorny problem? Not the Church, alas! which was systematically sidelined.

MSGR. DUPUCH’S SETBACKS

Msgr. Dupuch, whose zeal was tireless, often had to complain about the petty harassment of the central and local administration. It is not surprising when one knows that all the governor generals of Algeria, with one exception, were Freemasons. « The administration has other things to do than dealing with trifles touching on freedom of conscience. It has the right and the duty to prevent anything that tends to trouble public order, and, therefore, to oppose the conversion of Muslims », a note from the Ministry of War decreed in 1834 (quoted by Msgr. Pons, La nouvelle Église d’Afrique, 1930, p. 107).

So it was that on November 10, 1845, the director of the city hospital of Algiers ordered the crucifixes removed from the rooms, and sent to the Ministry of War a report that aimed at expelling the Daughters of Charity from service in the hospitals. The bishop was forbidden to have a catechism printed in Arabic and even to have his priests taught Arabic. A sentry was posted at the doors of the cathedral of Algiers to prevent Muslims from attending Catholic religious ceremonies!

Despite these constraints, the translation of a relic of St. Augustine, whose body was at Pavia, gave Msgr. Dupuch the opportunity in 1842 to recall on what foundation the Church of Africa should be restored. The ceremony took place with the participation of the army and a large number of the faithful and Muslims. Yet disagreement with the administration became each day more blatant. On several occasions, the offices of Algiers informed the bishop that he only had jurisdiction over Catholics.

Crippled with debts that were incurred by supporting his clergy and his works, he was forced to resign in 1845. In a letter to Gregory XVI, the unfortunate prelate confided his bitterness:

« When it comes to the army, agriculture, commerce, industry, civilisation, colonisation, to the colony’s more or less extensive systems and plans of all sorts; nothing is forgotten. But it is a sin, a crime to speak about God, Jesus Christ, and the Cross. Not once were these names pronounced in the speeches and official acts of Louis-Philippe’s Algeria… »

Before re-embarking for France, Msgr. Dupuch found refuge with M. de Vialar, the blood brother of the superior of the Sisters of Saint Joseph.

AN EXEMPLARY COLONIST

Baron de Vialar, the King’s prosecutor at the tribunal of Épernay, resigned in 1830 out of fidelity to Charles X.

In 1835, charmed by the beauty of the land of Algiers, Augustin de Vialar decided to settle in what he called his second country:

« What deep satisfaction I felt in seeing the European and African populations draw closer together, get along with one another and mingle! Here the Bedouins announce their merchandise, their foodstuffs in French, and receive the price in our money. Further on, Moorish workers toil with French workers. A rather large number of the children of the country already know French reasonably well and can serve as interpreters. »

« Agriculture is the surest, the most solid investment, he added, but agriculture must be carried out with wisdom, perseverance and without a methodical mind. » He bought land with the project of settling workers from his native Dordogne there as tenant farmers and later on making them into farmers. The project took shape, but our gentleman colonist did not stop there. He saw all too well that the only way of perpetuating the colony was to bring ourselves closer to the natives. We were in 1834, right at the beginning of the occupation. While Paris did not know whether to remain or not, de Vialar forged ahead. On June 30, 1834, braving the danger, he went to the market of Boufarik, in the heart of the Mitidja, a large marshy region southwest of Algiers, in company with an interpreter friend and a few soldiers. The people there only consented to selling them a dog. But the first step had been made. Eight months after this act of « conciliation », the army established a camp at Boufarik. Soon, close by the camp a modest wooden shed was built to serve as a field hospital for sick natives.

While the official colonisation was considered to be an individual matter, free of direction by any order or social hierarchy, Baron de Vialar conceived his mission as being one of paternity shown to the natives: « we ought adopt them definitively as our sons; as their fathers we ought slowly raise them until they became permanently like us in all things » (CRC n° 107, July 1976, The Catholic Mission of France; excerpts published in CCR n° 294, March 1997, pp. 29-30). He knew perfectly well how to make European and native families work together. The Arabs were employed in the activities to which they were accustomed: taking care of flocks, ploughing; the Europeans in other works: driving wagons, scything, horticulture. Everyone profited by it.

His farms were such models that some awarded him the title « father of colonisation ». Workers there were treated in a humane way. They left first thing in the morning to carry out their tasks, and in the evening they went to lodge elsewhere in order to escape the malaria that caused terrible devastation in the plain. « Beginnings are painful, Vialar used to say, but the future that they promise is so beautiful, so useful, so great, that one cannot be stopped. My heart heats up and enthusiasm doubles my strength. »

He had several legitimist friends like himself who applied the same principles. In the region of Oran, a certain Dupré de Saint-Maur, from Brittany, initiated a family-like system of farm management with twenty-five families of European workers and the same number of Moroccan ones. They succeeded in clearing and bringing under cultivation several hundred hectares. At the centre of the property stood a chapel. Dupré de Saint-Maur used to say: « I did not come to seek fortune; I came to venture part of mine; it is a worthwhile task to know how to risk capital in order to make productive a land soaked by the blood of so many Frenchmen. »

OUR LADY, REGENT OF AFRICA

Msgr. Pavy, who succeeded Msgr. Dupuch in 1846 in the episcopal see of Algiers, was the true organiser of the Algerian clergy. They were an admirable clergy, about whose heroism one could never speak enough. They lived in conditions of poverty and in the midst of unimaginable contradictions; at the end of twenty years they already counted a hundred victims in their ranks.

Msgr. Pavy, who succeeded Msgr. Dupuch in 1846 in the episcopal see of Algiers, was the true organiser of the Algerian clergy. They were an admirable clergy, about whose heroism one could never speak enough. They lived in conditions of poverty and in the midst of unimaginable contradictions; at the end of twenty years they already counted a hundred victims in their ranks.

“ Resurgens non moritur ”, The Church of Africa that is rising will not die! The proud motto of the new bishop conveys his apostolic zeal and was no illusion. During the cholera outbreak in 1849, he consecrated his diocese to the Sacred Heart. In Oran, he inaugurated the chapel of Our Lady of Santa Cruz in fulfilment of a vow he had made during the same epidemic.

At Algiers Msgr. Pavy wanted to build a sanctuary in honour of Our Lady of Africa. A bronze statue was placed in a grotto near the sea in expectation of the veneration that it would receive in a basilica built for this end. The bishop’s desire was to « spread to Algeria the vow of Louis XIII, who had chosen Mary as patroness of France ».

This Marian sanctuary would be « the religious centre, the arc of the covenant of Algerian piety ».

REPUBLICAN UTOPIAS AND IMPERIAL CHIMERA

Far from the Catholic, royal and communitarian ideal that was practiced by our legitimist colonists, the colonial policy of France evolved from 1848 to 1871.

In 1848, Algeria was declared to be a full-fledged part of France and was divided into three departments; during the Second Republic’s short lifespan a new colonisation project was launched. Some thought that in order to reduce the unemployment that was rife in Paris, the unemployed workers should be sent to Algeria. Lamoricière, who was then Minister of War, was charged with the enterprise, but he did not believe in it. What indeed could these people uprooted by politics do in a hostile country like Algeria in 1850? He was right. Two years later, more than half had abandoned Algeria.

The French of Algeria had welcomed the Republic enthusiastically, but they gave a more than reserved welcome to the Prince-President, especially when he proclaimed the Empire in 1851. (Napoleon III)

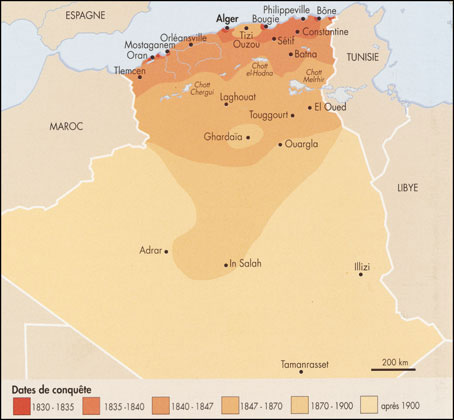

Nevertheless, the colony prospered and grew. A new holy war threatened to cause unrest in the territories of the South. Laghouat was conquered by main force in 1852. Then it was the turn of Kabylia in 1857. But to subjugate is one thing, to administer and govern wisely is another.

Since in Paris capital became the only criterion for selection, hope was placed in big development companies. The era of big-time capitalism had begun. It is noteworthy that it was in eastern Algeria, in particular in the region of Constantine, that this extensive colonisation was practiced the most. The consequences became apparent at the beginning of the Algerian War, because these zones, which were less well-administered, very rapidly fell under rebel control.

In the cities of Algeria, the republicans aroused the colonists’ discontent against the soldiers. The newspapers were full of insults for the « arbitrary, corrupt, brutal sabre regime… ». Their complaints went back to Paris where a Ministry for Algeria that bypassed the power of the army was created. But the existence of this ministry was short-lived.

Napoleon III, in fact, wanted to visit Algeria. « The conquest, he declared, can only be a redemption, and our first duty is to take care of the three million Arabs that fate born of arms has placed under our dominion. We must raise the Arabs to the dignity of free men, extend to them the benefits of education, while at the same time respecting their religion… This is our mission; we will not fail in it. »

When he returned to Paris, he abolished the Ministry of Algeria that had just been created, gave power back to the army and surrounded himself with arabophiles, like Ismaël Urbain, who had converted to Islam. « Strictly speaking, Algeria is not a colony, but an Arab kingdom, the Emperor explained pompously. The natives, just as much as the colonists, have an equal right to my protection. I am just as much Emperor of the Arabs (sic!) as I am the Emperor of the French. »

It is superfluous to say that such a chimera plunged Algiers into turmoil. From the governor to the bishop, irony vied with anger. Paris, nonetheless, resolutely implemented the project: a senatus consultum on July 14, 1865 declared that the Muslims were French and that, if they applied for it, they would receive the status of French citizens. In 1870, there were 270 who applied for it out of three million subjects…

LAVIGERIE SET OUT TO CONQUER AFRICA

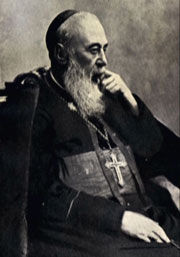

For his part, Msgr. Lavigerie, the new archbishop of Algiers, was making sensational declarations after his arrival in May 1867.

Up until this time, this prelate was more familiar with what was going on behind the scenes in the government than in missionary congregations. Even so, a grandiose project haunted his thoughts: to regenerate the whole of Africa from Algeria become Christian once again.

As the liberty of the apostolate required, he did not delay in crossing swords with the administration of the colony, in particular with the Municipal Council of Algiers that wanted to replace the teaching brothers with lay teachers. Not having won his case, he was imprudent enough to combine his demands with those of civilians against the army.

At the same time he brought in twelve Premonstratensians from St. Michael Abbey in Frigolet to finish the construction of the basilica of Our Lady of Africa and to be in charge of the sanctuary. They were called “ White Fathers ”, because of their habit. But the archbishop, who entertained the project of a missionary congregation, did not rest until he had replaced them by his own missionaries, who kept the name of “ White Fathers ”, and he sent the Premonstratensians back to Provence.

APOSTLES OF THE MUSLIMS?

The idea of a missionary Order was not Lavigerie’s, as Fr. François Renault, his most recent biographer establishes: « Shortly after his arrival at Algiers, Lavigerie received from a Jesuit, Fr. Ducat, who had formerly lived in the country, a plan to organise a religious society called “ Missionaries of Our Lady of Africa ”. The order would be comprised of priest and lay brothers and was to be established in a Muslim setting in order to provide schools and orphanages, to care for the sick, and to open old people’s homes. At the same time it would extend its relations into the tribes in order to form a catechumenate, if possible. This plan, although carefully examined by its addressee, remained unimplemented for the moment. An event took place that allowed the beginning of its realisation. The superior of the major seminary, Fr. Girard, a Lazarist, was aware of the various attempts that had been made during Msgr. Pavy’s episcopate to approach the Muslims, and their failure pained him.

« He spoke about them to the seminarians expressing the hope that volunteers would come forward to resume them. Three seminarians offered their services and, after having reflected and prayed at length, the superior presented them to the archbishop. It was at the end of January 1868... » (Le cardinal Lavigerie, l’Église, l’Afrique et la France, Fayard, 1992, p. 165)

The novitiate opened in October 1868, at the same time as two institutes, of Brother and Sisters, « farmers and hospitallers », intended to support the Fathers in their apostolate, « three branches of a single family, working together and with common accord to obtain the extension of the Kingdom of Jesus Christ ». These foundations were scarcely laid when a series of appalling calamities hit Algeria required all their devotion.

THE TERRIBLE YEARS

In the heyday of the liberal Empire, it was thought that Algeria was entering into the era of prosperity. Great economic projects were constructed… But drought made the harvest of 1865 very mediocre. The crops of 1866 were ravaged by locusts. The following year an early cold spell decimated the flocks and worsened the food shortage. The nomads of the high plateaux experienced an unprecedented famine. Typhus and cholera struck these poor people: it is estimated that there were 600,000 victims in the span of six years!

Since the imperial government delayed in releasing aid, the appeal of Msgr. Lavigerie and Pius IX stirred Catholic charity. The Archbishop alone took in almost 1800 orphans, to whom the brothers and sisters devoted themselves. Land was acquired at Attafs in the plain of Chelif with the intention of forming Christian villages. Msgr. Lavigerie considered these orphans the initial nucleus from which he could progressively realise his grand, longed-for project: the renovation of Africa.

When the Empire collapsed under the blow of defeat, a few hotheads, including a certain Vuillermez, a one-time deportee from the revolutionary days of 1848, took advantage of it to create a “ Commune ” that resembled the one in Paris. They demanded the abolition of the military regime. This was soon accomplished by means of the decision of the delegation of Tours, where the Jew Adolphe Crémieux sat. Among the fifty-eight decrees (!) concerning Algeria, there appeared one that naturalised the Jews of the colony en masse. This time it was the natives’ turn to rebel.

« I cannot accept your Republic, declared Mokrani, the head Kabyle of the Medjana, to a French officer, because since it was proclaimed, I see monstrous things: your generals – before whom we were fully subjected and respectful like servants – are insulted, and they are replaced by profiteers and Jews, and you think that we are going to accept that! » Soon the entire east of Algeria answered his call, and a hundred thousand Kabyles rose up, blocking the roads and the approaches to the cities, massacring isolated colonists.

Emergency reinforcements were sent from France. A ten-month campaign was necessary to quell the revolt, the most important one since Abd al-Kader and the last one before the War of Independence. The repression was fierce.

REPUBLICAN ALGERIA

After the defeat of 1870 and the revolt of the Kabyles, a new period opened for Algeria. Civilians had theoretically replaced the military, but it was necessary to wait for the advent of the “ true Republicans ” in 1879 in order to see the first civil governor debark at Algiers and thus realise the change in “ regime ”. Little by little, the officers of the Arab Offices disappeared, except in the Territories of the South where the army retained power for a long while yet. From 1881 on, most of the administrative services were joined to the Parisian ministries. By extending individual property and the development of public education, the republican government thought it would “ assimilate” the natives. French laws would be applied to Muslims: in this way they would gradually become French...

But this presumptuous legislative “ assimilation ” poorly concealed a withdrawal of the government. Despite the promulgation in 1881 of the Code de l’indigénat1, it was necessary to face the facts: a Muslim could not be governed like a Frenchman. The Jacobin and republican manner of “ assimilation" was a chimera. Powers were thus given back to the governor general.

There remained the secular and compulsory school, the great hope of our intransigent republicans. « The primary school was the cornerstone of the Republic; Governor General Jonnart stated in 1910; it will be the foundation of our domination in Algeria. » France had been in Algeria for 80 years and, if this good Jonnart is to be believed, everything still remained to be done. Actually, it had been thought more useful to build minarets instead of steeples, to create Koranic schools instead of Catholic schools. In 1898, the French state had the construction of 20 mosques to its credit, and it maintained more than 400! At the same time, the Jesuits, who were accused of “ proselytism ”, were forced to abandon their admirable missions in Kabylia.

THE MISSION IN KABYLIA

We must go back a few years in order to relate this little known missionary epic, but it is so instructive and edifying! The mission was begun by a Jesuit, Fr. Jean-Baptiste Creusat, shortly after the conquest of the Kabyle land in the beginning of the 1860s; it promised abundant fruits. The natives themselves had, on several occasions, requested the presence of missionaries. A kaid admitted to the Father: « Our ancestors walked in the ways of the Gospel; we will end up coming back to it. » Accompanied by a brother who assisted his missionary work, Fr. Creusat began visiting the tribes, assisting the sick and the poor there. The cassock was not an obstacle – on the contrary! – it won him a good, cordial welcome everywhere. It is noteworthy that for a people who are so jealous of the inviolability of their soil, two or three villages offered the missionary rights of citizenship, and one of them even proposed that he use one if its mosques in order for him to gather the children there and to teach them the « the straight and narrow way ». The Jesuit continued his apostolate thus for several months, « discretely, without arousing in the tribes any complaint against France and Christians. Quite the reverse, the immense majority of the Kabyles regarded with favour the overtures of this new marabout who resembled their own so little, who was so scholarly, modest, disinterested and so charitable, who never asked for anything and who was always prepared to give. » (Le Père Jean-Baptiste Creusat, Biographies jésuites, t. I)

But one day from Algiers arrived a ban on his making such errands in the villages « under the guise of charity » and on settling in the heart of Kabyle country. Heartsick, the zealous apostle had to return to Algiers.

It was not until 1873 that Msgr. Lavigerie was able once again to send missionaries to Kabylia with the support of the governor general, Vice-Admiral Count de Gueydon, a Norman Catholic and legitimist, who declared: « I spent my life protecting the Catholic Missions on all the seas of the globe. I cannot accept that they be persecuted on French soil. It requires much reserve, much tact; one must act by providing services and not by making discourses. But the time seems to have come at last for gradually associating the people whom we conquered with Christian civilisation. »

At last! Five posts were then created in Kabylia: two for the Jesuits and three for the “ White Fathers ”, who then launched into their apostolate.

Fr. Joseph Rivière, a Jesuit missionary whose heart was consumed with zeal and devotion for the Sacred Heart of Jesus, was appointed to the post at Djema-Sahridj. He straightaway conquered the population of the entire region, in particular the children, whose teacher he became. Having the gift of tongues, he soon perfectly spoke Kabyle and wrote the first French-Kabyle dictionary. But soon, alas! the former instructions were reactivated: an absolute ban on all direct apostolate to the natives.

In 1880, the Jesuits were expelled and charged with “ corruption of minors ”! Our missionary related: « With the help of God, our children were being educated. Several of them, without us knowing it, had obtained catechisms that they were studying ardently. A time came when there was among them a general attraction towards our holy religion. They wanted to attend Mass and benedictions of the Blessed Sacrament, etc. It would have been too much at the time. One of them, to make up for it, got the idea to construct a small shrine in the fields; he lined the back wall with a foulard on which he attached images, and there he spent hours in prayer. This child, through his repeated insistence, ended up obtaining permission to go to France in order to receive holy Baptism and undertake ecclesiastical studies. Several others expatriated themselves in order to be able to follow the call of God. At the moment of the expulsion, eighty of the hundred and forty students were registered for being baptised at the first favourable occasion.

« What has become of them since? Alas! Most of them returned to type, and the Devil can take delight in having thrown us out. »

Yes, alas! But the most scandalous thing is the archbishop’s complicity with the persecuting authorities.

THE REPUBLICAN CARDINAL

The Archbishop of Algiers did nothing to defend the Jesuits. For a long time already, he had yielded before the republican administration and forbade his missionaries to engage in any proselytism. The “ missionary ” bishop came to the point of modifying his own project: « Missionaries must be initiators above all else, but the enduring work must be carried out by the Africans themselves, who will have become Christians and apostles. It must be pointed out here that we mean that they will become Christians and apostles and not Frenchmen or European. It would be nonsense to make Europeans or Frenchmen out of them. They would become, by that very fact, even less capable of doing the work that they must accomplish. » (Directives of 1874, quoted by Renault, p. 296)

In his heart, the Archbishop of Algiers had already given up on converting the Muslims of North Africa. Another “ grandiose ” project kept his mind occupied: restoring the ancient see of Carthage, which is close to Tunis, in order to occupy it and pose as the successor of the great St. Cyprian. This is how he took advantage of the French intervention in Tunsia (April-May 1881) in order to have himself recognised as the apostolic administrator of Tunisia both by the Holy See and the French government, and in order to obtain the eviction of the Italian Capuchins who had had responsibility there for years!

So many good and loyal services in the service of the Republic indeed merited him a cardinal’s hat. In 1882, it had been obtained. Gambetta, whom Lavigerie considered « as a man of rare value » (!) was not the last to rejoice over it. It was the era when the archbishop of Algiers, who was passionate for republican politics, advocated an agreement between Catholics and moderates against “ extremists ”: on the left like Clemenceau, or on the right like Msgr. Freppel, whom he denounced to Leo XIII as « the declared and insolent enemy of Your Holiness’ politics » (sic!)

In 1888, the republican cardinal embarked on an international campaign against slavery, which Lavigerie presented to the Pope as follows: « The Church should take the head of a great humanitarian combat, a solid foundation for bringing together good wills. »

Actually, it did not amount to much since slavery and the slave trade was in the latter nineteenth century conducted by local Muslim leaders. An international conference was absolutely powerless to prevent them from pursuing their shameful dealings. The colonising framework of European nations and the missionary zeal that goes hand in hand with the advance of civilisation were required…

Scarcely had Lavigerie recognised his failure than Leo XIII entrusted him with another mission. The cardinal considered it as « the most formidable act of his life »: the rallying of French Catholics to the Republic. « Formidable » because the French monarchists were the main support of his African missions. When consulted on the consequences of such treason, Msgr. Livinhac, the superior in charge of the White Fathers, replied: « If the Holy Father orders it, you have only to obey without taking us into account. »

After having delivered the “ toast of Algiers ”2 on November 12, 1890, a prelude to the Letter “ Au milieu des sollicitudes ” (On the Church and State in France) on February 2, 1892, Cardinal Lavigerie could die satisfied on November 25, 1982, with all the honours of the reconciled Church and Republic.

« A CHURCH HALF IN RUINS »

His successors saw the ruins pile up. With the coming of the radical Socialists to power in 1899, Algeria’s public establishments were secularised; sisters were turned out of hospitals, orphanages and schools.

Fr. de Nantes has often said to us: at the same time that France brought to the subjects of her colonies the know-how of Western civilisation, which is fundamentally Christian, all the pride of our political secularism and technology was also transfused into them.

Nevertheless, beyond these official defects, the colonial work continued thanks to the relentless work of colonists, whether grand or small, who day after day yielded enough from this savage land to provide for their compatriots. It was the colonists – and the soldiers – who made Algeria.

THE CONQUEST OF THE SAHARA

In itself, the conquest of the Sahara suffices to illustrate the magnificent work accomplished by France in Algeria in spite of the Republic. The enterprise began when our army, tired of the incessant raids of the pillagers from the south, captured Mzab in 1882. In 1889, they organised a “ geological ” expedition in the regions of the South Sahara. The Flatters column, which had attempted it ten years earlier, were massacred by the Touareg. This time, the column was well armed. Its scientific cover was only a subterfuge to deceive the administration. As was foreseeable, the column was attacked by the Touareg. But our soldiers were there, and they pursued them and seized In Salah. Paris made a terrible fuss. They let the storm blow over, while promising that they would go no farther… It was too late! For to keep In Salah, it was also necessary to pacify the neighbouring oasis and to secure the caravan tracks.

It was François-Henry Laperrine’s hour. « It is he, wrote Father de Foucauld, who gave the Sahara to France, despite herself, and at the risk of his career… » In 1902, the legitimist officer from the Béarn on his own initiative created the Saharan Companies, nomadic troops composed of natives commanded by French officers. They were only recognised by the State three years later after having proved their worth. They were allowed to take control of the entire Sarah and with limited means established French peace in the space of a few months. It is true that Father de Foucauld, the « universal brother », was there; his goal was to accompany Laperrine’s columns and, alongside them, to civilise the Touaregs, to make them love the true France!

Tunisia was conquered in 1881 and Morocco in 1907. Both required this because they were the source of incursions of a ferocity that had made the Barbary States infamous. France had succeeded thereby in taking control of a vast empire that had formerly been Roman and that covered the whole of North Africa. Implanting our holy religion there yet remained … Father de Foucauld arrived in due time, but what obstacles remained to be overcome in our institutions more than in our subjects!

FATHER DE FOUCAULD, THE « UNIVERSAL BROTHER »

« Pray for all the Muslims of our northwest African empire, which is now so vast, Father de Foucauld wrote to Marie de Bondy in 1912. The present hour is grave for their souls as it is for France. For the eighty years that Algiers has been ours, we have been so little preoccupied with the salvation of the souls of the Muslims that it might be said that we took no interest in it. We did not take any greater care of governing them well or of civilising them. We maintained them in a state of submission and nothing more. »

Fired by love of Jesus alone, Brother Charles of Jesus arrived at Beni-Abbès in 1901. For him, there was no other project other than to radiate the love of Jesus. The most pure charity drawn from the Heart of Our Lord brought him towards the most abandoned of men. Nevertheless, his outstanding realism and intelligence made him discover at their source, which is divine charity, the entire French colonial spirit, ordered to the extension of the Kingdom of God, brought back to light today by our Father, Fr. de Nantes.

Fired by love of Jesus alone, Brother Charles of Jesus arrived at Beni-Abbès in 1901. For him, there was no other project other than to radiate the love of Jesus. The most pure charity drawn from the Heart of Our Lord brought him towards the most abandoned of men. Nevertheless, his outstanding realism and intelligence made him discover at their source, which is divine charity, the entire French colonial spirit, ordered to the extension of the Kingdom of God, brought back to light today by our Father, Fr. de Nantes.

The first observation: it is the Army that pacified and continues to do so, by protecting the weak from the strong. To defeat the enemy, punish the rebels if there are any: Father de Foucauld was in favour, for he saw the immediate benefits. But it does not suffice to dominate. One must then govern, by annexing the conquered country rather than by establishing a protectorate, because the protectorate is a « false regime », which does not sufficiently express the « colonial bond », a bond of paternity and, in return, of filiation. The protectorate keeps existing authorities, which often are nothing but tyrannies. The administration? Father de Foucauld wanted it to be direct, close and effective, led by carefully selected officers who had resided there for a long time and had a perfect knowledge of the country. If he deplored the abuses and incapacities of our administration, he never contested or impeded its action. It is truly because he held a very lofty idea of France’s role in her colonies that he could not support mediocrity.

He had understood that to make the natives into Frenchmen required an immense and persevering effort. It was a total work of colonisation and Christianisation that had to be undertaken. « As long as there is a Muslim in North Africa, he said, we will have an enemy! » Here he touched the weak point: « Was this effort of conversion supported by the government? No, alas, it was quite the opposite! While we Catholics were faced with systematic opposition from public authorities, they encouraged the Muslim religion. They committed by the very fact a sort of suicide, for I must indeed say that Islam is our enemy: we will always be the despised “ roumis ”. »

Father de Foucauld did not abandon the conversion of the Muslims for all that. He believed this conversion would be possible through the redemptive power of the Blood of Jesus, « the Master of the impossible », who forbade His disciples ever to be discouraged. He quoted one of Msgr. Freppel’s sayings: « For God does not command us to win, but to fight! » For his part, he strove only to « civilise the natives ». He fervently wished that since the apostolate was forbidden to the religious, “ laymen ”, like new Pricillas and Aquilas, would join him and settle in the midst of the native populations. They would preach to them by example and silent influence « in order to gain their confidence, familiarise them with us and Christianity ». To this end, he founded the Catholic Colonial Union in 1912.

He experienced a situation similar in every respect to the one that our army had to confront in 1954: the implacable bands, the hesitating populations, the precariousness and insufficiency of military resources, disagreements among « Christians ». This is why the doctrine and the example of our Blessed Father already sheds light on our study of the War of Algeria.

SONIS THE AFRICAN

GASTON de Sonis was among the most conscientious, the most courageous and the most devoted that the Army of Africa had known. In the space of sixteen years, he travelled throughout Algeria in all directions: Algiers, Blida, Miliana, Tizi-Ouzou, Mascara, Ténès, Laghouat, Mostaganem, etc. Since he knew Arabic perfectly, he mixed closely with the Muslims. He also spent entire nights before the Blessed Sacrament, was consumed with the devotion of a child and knight for Our Lady of Africa and, after providing his family with the sustenance it needed, he distributed what remained in alms for the poor.

GASTON de Sonis was among the most conscientious, the most courageous and the most devoted that the Army of Africa had known. In the space of sixteen years, he travelled throughout Algeria in all directions: Algiers, Blida, Miliana, Tizi-Ouzou, Mascara, Ténès, Laghouat, Mostaganem, etc. Since he knew Arabic perfectly, he mixed closely with the Muslims. He also spent entire nights before the Blessed Sacrament, was consumed with the devotion of a child and knight for Our Lady of Africa and, after providing his family with the sustenance it needed, he distributed what remained in alms for the poor.

In April 1861, when he was commander of the military circle of Laghouat, the advanced post of Djelfa was attacked, and about thirty colonists had their throats slit. As soon as he had been informed, Sonis assembled a goum and rushed to the scene of the drama. Arriving in the early hours of the morning, he surprised the assassins, who had again massacred several colonists during the night, including a child in his crib. He organised a court-martial, judged them, and had seven of them shot along the wall of the fort.

« By having the perpetrators of this unprecedented crime executed immediately, he wrote to his superior, I am conscious of having carried out a duty. I was in the presence of a dumbfounded population; I had to reassure it. I also wanted to prove to the fanatics that they could not count on impunity for their crimes, less yet that they had a chance of escaping or of making an easy defence. »

But at Algiers, a journalist picked up the story. The Masonic lodges became agitated, and Marshal Pélissier, who was governor of Algiers at the time, reprimanded Sonis and relieved him of his command. A year had not gone by, however, before rebellion once again broke out and caused new massacres. The governor had to send troops to re-establish order. Sonis wrote: « We do not want to have a clear understanding. We do not understand that fundamentally this is a religious quarrel and that the Arabs will never forgive us for not being Muslims. We took things the wrong way round, and we became teachers of fanaticism. We built mosques when no one asked us to do so, we Christians who do not have churches. We are reaping what we have sown. I indeed fear that the arm of God will weigh down on this poor French people who did not come to this land of Cyprian and Augustine without a secret plan of divine mercy and who, alas! have so totally failed in their mission. »

Sonis « was a just man in his actions, words and command, an Arab soldier who served under his orders testified. Lies and calumnies did not find the door to his mind. He was a valorous warrior whom sabres never made retreat. His voice thundered on the days of combat, and his heart remained firm in the midst of the battle. He was the most brilliant cavalryman. His piety made him pleasing to God, and his religion was the reason we loved him. »

Brother Matthew of Saint Joseph

1) An administrative system applying to indigenous populations of French colonies before 1945.

2) The toast of Algiers: In 1890 Msgr. Lavigerie arranged with Pope Leo XIII to attempt to rally French Catholics to the Republic. He invited the officers of the Mediterranean squadron to lunch at Algiers, and, in a toast he made, he renounced his monarchical sympathies, to which he had clung as long as the Comte de Chambord was alive, expressed his support of the Republic, and emphasised it by having the Marseillaise played by a band of his White Fathers.