Explanation:

THE PERFECT RELIGION

I. A Jewish Prayer

Recalling the story of Charles Forster, who thought that he had found the translation of a southern Arabic inscription in a poem by Al-Nuwayrī, an Arab author of the 13th-14th century (1279-1332), Jacqueline Pirenne draws a lesson from it that we must extend, at the conclusion of this first volume, to the translation of the Qurʾān itself. Indeed, what was the error of this “unfortunate Irish pastor”? It consisted in “being unaware of the way Muslim authors of past centuries wrote history: they showed little concern for providing translations of ancient texts that they probably could no longer even read. They collected hearsay and traditional poems and turned them into a story, peppered with legends, confusedly organised with actual historical data, within a general framework borrowed from the biblical genealogy of Ishmael and Solomon.” The conclusion to be drawn: “There was no connection between the traditional Arabic poem and the Arabic text, forgotten on its rock, facing the sea.”●

The same holds true for the Qurʾān. Father Lammens, who had sensed this at the beginning of the 20th century , ardently desired a scientific exegesis of the Qurʾān. Such an exegesis reveals that there is only the remotest connection between the commentary of the Muslim authors of past centuries and the literal meaning of the Qurʾānic text.

What does this literal meaning reveal to us at the stage we have reached?

1. A JEWISH PRAYER

According to Nöldeke, Sūrah 1, or “song (canticle)” might just as well be Jewish or Christian, since there is nothing Muslim about it: “Here, the specific Islamic complexion disappears to such an extent that this prayer could be found in any Jewish or Christian devotional book. This is precisely why it is so difficult to answer the question of its dating.”●

The scientific exegesis of this text forces us to call into question the judgement of the great Semitist. Is this “prayer of benediction” Jewish? It certainly is, not only because of the ideas and sentiments that it contains, but also by the language used to express them. Consequently, and to the same extent, it is profoundly anti-Christian. Straightaway, this offers an initial response to the question of the dating of this prayer, when the effort is made to place it in a historical context by using the positive data of epigraphy and non-Muslim sources, and not the legendary information furnished by Arabic sources.

THE GOD OF THE OLD TESTAMENT

The seven verses of Sūrah 1 invoke “the God” using four different names, and addressing four requests to him that leave no doubt as to his identity: this God can only be the God of the Bible.

This, moreover, is what the use of the definite article from the very first verse suggests : ʾilāh, which is only the amplified form of ʾil, the name of “any god” in the Semitic pantheon.● The use of the definite article ʾal points to a determined “God:” ʾal-ilāh, which has become through contraction ʾallāh “the God.”

Which God?

The answer is conveyed in the immediately following expression: ʾar-raḥmāni r-raḥīmi, in apposition to the “name of the God” Whom has just been blessed. This expression is God’s very definition, just as in the book of Exodus, riḥamti èt-ʾašèr ʾaraḥèm defines the “Name of Yahweh” uttered by Yahweh before Moses (Ex 33:19), and ʾèl‑raḥûm, defines the Name of Yahweh “proclaimed” twice by Yahweh before Moses (Ex 34:6.)

ʾar-raḥmāni r-raḥīmi, “the Merciful One, full of mercy” thus explicitly designates the God of Horeb in the very act of His revelation to Moses.

“Master,” rabbi● is unusual, but it seems to be specifically characteristic of the Jews of Arabia● who never give this title to a rabbi, in order to “avoid blasphemy.”● This is as good as a signature. This divine name: rabbi, is foreign to the whole rabbinical tradition as it is to the Old Testament. It derives from the Aramaic rab and passed into the Greek of the New Testament: rabbi, wherefrom the author of this prayer seems to have taken it directly. What is his intention in doing so, if not that of depriving Jesus of this title that His disciples gave Him? (Mk 9:5; Mk 11:21; Mk 14:45; four times in The Gospel According to Saint Matthew, eight in The Gospel According to Saint John). Then he applies it to “the God” of Jeremiah, who announces that in the days of the new Covenant, everyone will be taught by God Himself (Jr 31:33-34; cf. Is 54:13 quoted by Jesus, Jn 6:45). The history of Judeo-Christian rivalries in Arabia● tends to support this hypothesis.

“King,” mālik●, is transposed from the biblical Hebrew mèlèk. Yahweh is invoked in the Bible under this name in benedictions, praises and doxologies, particularly in the Psalms traditionally attributed to David (Ps 5:3; Ps 10:16 and passim.)

Thus, the first four verses of the Qurʾān summarise the whole Bible by using these three names: ʾar-raḥmāni r-raḥīmi “the Merciful One, full of mercy,” summarises the Law of Moses; mālik, “King” evokes the sapiential books in which all the wisdom of king David and Solomon are contained; rabbi, “master,” announces the teaching of the prophets.

The feelings immediately expressed correspond well to the content of these three parts of the Bible:

“the love” ʾal-ḥamdu, of the God rabbi●, summarises all the moral teachings of the prophets: “You shall love Yahweh your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might.” (The Book of Deuteronomy 6:5; cf. Ho 6:6; Jr 31:33)

“O You whom we adore!” ʾiyyāka naʿbudu (Q 1:5): this exclamation summarises the whole Law. It springs from the pure commandment of Moses: “Him [Yahweh God] shall you adore,” ʾotô taʿabod” (The Book of Deuteronomy 6:13)

“O You of whom we want to sing in alternating choirs!” ʾiyyāka nastaʿīnu (Q 1:5): this invocation announces that “love” and “adoration” will be expressed in the psalmic mode, which immemorial tradition has attributed to King David: “Sing, ʿènû, to Yahweh”(The Book of Psalms 147:7)

It all ends with a request: “Deign to show us the narrow path of survival.” (Q 1:6) Which “path”? The one that is taken by “those on whom You have poured out your sweetness.” (Q 1:7) Who are they? To what “survival” does this “path” lead them? The exegesis of Sūrah 2 will allow us to answer these questions. First, however, an attempt must be made to assign a date to Sūrah 1.

JEWISH PROSELYTISM IN YEMEN

In the years 1922-1924, René Aigrain formulated well the postulate that still prevails today among historians: “Before Islam, Southern Arabia really has a particular history, very different from that of Northern Arabia, while the history of the Ḥiḏjāz, being a region crisscrossed by caravans, must a priori bear a certain resemblance to both the North and the South.”●

A posteriori and all having been examined, such is not the case. Although the inscriptions brought from Yemen by travellers, whom the pioneers of the last century remain Joseph Halévy and Edouard Glaser, received the name of “inscriptions from South Arabia,” the expression is misleading: “It does not lead us suspect that the south Arabic texts were found in the north of the Arabian peninsula and, even less, in Ethiopia.”●

The meagre data from these epigraphical discoveries combined with those provided by Church historians allowed me to shed light on two facts in studies supervised by the late Cardinal Daniélou●:

1° From the end of the 4th century a.d., South Arabia, far from being “apart,” played a major role in the history of the whole Arabian Peninsula.

2° At the end of this 4th century, Yemen was the setting for a vast enterprise of Judaisation without precedent or equivalent in the East in those days.

FROM SABAEAN PAGANISM TO MONOTHEISM

In fact, the inscriptions show us, around 280, Schamir Yuharisch, “king of Saba and Ḏū Raydān,” of “Hadhramōt and Yemenat and of their Arabs in both mountain and plain,” invoking Athtār, i.e. the stellar – and consequently pagan – divinity Venus●.

Now “around a century later, a series of distinctly monotheistic inscriptions in which ‘God,’ ʾilahān, or ‘ʾilān lord of heaven,’ or ‘of heaven and earth,’ who is repeatedly described as “the merciful One,” er-Raḥmān●: the rabbinical Aramaic keyword, is repeated twice in Sūrah 1●; and each time it is reinforced by its Hebrew equivalent, the transcription of the biblical adjective: ar-raḥîm!

What took place then between 280, the date of the inscription giving the titles of Schamir Yuharisch who invokes Ashera, and 378, the date of the inscription of Melikīkarib Yuha-min who invokes er-Raḥmān?● An event that Church sources allow us to piece together.

FAILURE OF THE CHRISTIAN MISSION

Philostorgius related a mission that Theophilius of Dibus, an Arian, carried out around 356 in the land of the Homerites. This mission can be situated after Frumentius’ in Abyssinia that Glaser wanted to locate in Yemen, but his system was too conjectural and was not followed.● The population of this country at that time practiced ancient Sabaean paganism, with the exception of a large Jewish minority, for “not a small number of Jews” were found there, whose “customary malevolence and untruthfulness” Theophilius had to silence.

Philostorgius assures us that the results obtained by Theophilus’ preaching and gifts were marvellous. Churches were built, the king was converted, and the Jewish intrigues had to go into obscurity. In reality, here Philostorgius is seeking to justify the Anomoean party. What interests us, however, and what we will retain is the background of the whole account: the Roman and Christian initiative comes up against an already well-established Jewish influence in Yemen.●

After his mission in Yemen, Theophilus of Dibus went to Abyssinia to deliver a letter concerning religious affairs to the king of that country on behalf of Emperor Constantius. A well-known inscription of Axum presents this king, named ʿEzana, as “king of the Axumites and of the Ḥimyarites and of Ḏū Raydān and of the Ethiopians and of the Sabaeans.” He was a pagan at the time when the inscription was engraved, “and invoked Ares (Mahrem in Ge’ez), with Poseidon (Beher)● and the Earth (Medr).”● The letter that Theophilus brought, however, is addressed to ʿEzana and to his brother, Sazanas, without marking any distinction of rank between them. Theophilus’ mission (356) is therefore subsequent to the inscription. In an inscription from a later period, however, ʿEzana declares that he worships the “God of heaven,” and no longer Ares and Poseidon.

All of this bears witness to the great political and religious upheavals in these countries. The titles of the king of Axum tells us first of all that Ḥimyar and Axum were then united under the same king. Which recent Ethiopian conquest brought about this union? How far did the Axumo-Ḥimyarite empire extend? If we are to believe Philostorgius, it extended as far as the emporium romanum of Hormuz, at the entrance to the Persian Gulf.

Above all, this king became a Christian, having a Christian bishop in his capital, Frumentius, and receiving Emperor Constantius’ embassies.

For how long? “In 378, the inscriptions show us the indigenous dynasty in power once again, without Axumite interference: ‘Melikîkarib Yuha-min, father of Abîkarib Asad and Waru-amar (Dar-u-amar) Aiman, after defeating the Romans (meaning their allies, the Axumites), as king of Saba, Ḏū Raydān, Yemenat and Hadhramōt and their Arabs pays homage to Sapor II, king of Persia.’ ” The inscription invokes “the Merciful” er-Raḥmān●

This thwarts Constantius’ grand vision. The failure is total. The Ḥimyarite reaction that drove out the Axumites is anti-Roman, pro-Persian, and anti-Christian.

“The son of Melikikarib Yuha-min, Abîkarib Asad (around 385-420), was succeeded by his own son Sharahbîl Yafur (420-455), under whom the first breach of the dyke of Mârib took place. This is attested by an inscription of 450-451 in which er-Raḥmān is invoked [...]. In 467, er-Raḥmān is still invoked by King Sharahbîl Yakkuf (455-470), his son Madîkarib Yanam who was to succeed him [...] and perhaps, as in an inscription of Taphar, Lahyathat Yanûf [...]. An inscription from Sanā, dated 458, mentions an Abd Kulâl who invokes er-Raḥmān.”●

These dynastic inscriptions profess a monotheistic faith that reveals the identity of the instigators of the anti-Roman, anti-Christian reaction: it is the Jews who, after the retreat of the Axumites constitute the only real intellectual and social elite of the country, and who, with the support of Persia, substituted “their” dynasty for the Christian dynasty.

A JUDAISING MONOTHESISM

Proof of this preponderant influence of Judaism on the “King of Saba, Ḏū Raydān, Yemenat and Hadhramōt” and on “their Arabs” is provided by an inscription due to Sahīr and his wife, which can be dated to the 5th century. This inscription gave rise to a controversy between Glaser and Halévy at the end of the 19th century: “Blessed and praised be the name of the Merciful One who is in heaven, and Israel and its God, the Lord of Juda.”● Maintaining in the teeth of all reason the Christian character of the monotheistic inscriptions of Yemen, Halévy wanted to read “Yasurêl,” the name of a Sabaean man contemporary with the inscription, instead of “Israel.” Yet it is really showing too much obstinacy in denying the obvious. For this text is clearly Jewish, and it attests to the identity of er-Raḥmān “the Merciful One.” He is “a God,” ʾilahān, who has been invoked in Southern Arabia since the end of the 4th century: he is the God of Israel, “the Lord of Judah.”●

Christian inscriptions are, in fact, easily recognisable. They also assign precedence to er-Raḥmān, but at the beginning of either a Trinitarian formula: “the Merciful One and His Messiah and the Holy Spirit,” or a Christological formula: “the Merciful One and His Son Kristos the Victorious.”●

After having discussed Halevy’s interpretation point by point, Glaser concluded in the wisest and most enlightening way for our purposes: “If Mr. Halevy does not find in this text all the forms and expressions commonly used by the ancients or by true Israelites, he should be kind enough to take into consideration that we are not dealing here with true Jews, but with Ḥimyarites converted to Judaism [emphasis added] and who probably had little regard for the formulas used by true Jews. The latter probably would not have left us votive or other inscriptions, neither in Arabia nor elsewhere, for they were not in the habit of informing posterity of their deeds by means of inscriptions, except when they wanted to preserve the name of a deceased person; for the rest, they used books, which for that matter are not so common.” Glaser concluded: “I found it interesting to show the great influence of the Jews in Arabia from the end of the 3rd to the 4th century of the Christian Era,”● adding that much remained to be discovered in this area.

Everything leads us, therefore, to conclude that in the 4th century the Persians supplanted the Romans in their effort to colonise Arabia, while the Christians in their missionary attempt were supplanted by the Jews, already firmly established in these places and, moreover, in constant contact with the school of Tiberias.●

Thereafter, the 5th century was a period of Jewish preponderance in Arabia, favoured by the decline of the old Roman Empire, the hereditary enemy of the Jewish people. Justinian’s efforts to restore this empire to its former glory met with fierce resistance from them: at Naples in 536, in Africa two years earlier, where the armies of Belisarius had caught them in the midst of the Judaisation of the Berber tribes, to the point that Justinian had to proscribe Judaism in Africa.

THE DATE; THE AUTHOR; THE LANGUAGE

With good reason, Blachère writes about Sūrah 1: “This text forms a whole that can clearly be distinguished from the rest of the Qurʾān.” Nöldeke, however, put “the question of its dating the wrong way: “to say that ‘the specific Islamic complexion disappears here’ is to suppose that this “complexion” was already present elsewhere, at the time when this prayer was composed. There, however, is no proof of this.

THE DATE OF ITS COMPOSITION: END OF THE 4th- BEGINNING OF THE 5th CENTURY

This Sūrah offers such impressive contacts with the “southern Arabian” inscriptions of the 4th and 5th centuries that one might well date it from this period, which we can describe as “pre-Islamic,” if not its redaction, at least its composition. In fact, coming from a community, as is shown by the repeated use of the first person plural: “we”● and from a Jewish community in Arabia, this Sūrah was subject for a long time to the law of synagogal prayer: “Whoever draws up in writing a prayer formula is comparable to someone who would burn the scroll of the Torah.”

“Between 600 and 650, this ban fell into disuse.● Thus its transcription in written Arabic must perhaps be traced back to this period. It so happens that other clues taken from the epigraphy confirm this hypothesis.

THE DATE OF THE WRITING OR THE BIRTH OF WRITTEN ARABIC: END OF THE 6TH - BEGINNING OF THE 7TH CENTURY.

Sūrah 1 is not only a testimony to the first effort to judaise Arabia, it is also the first known document of Arabic literature. The coincidence is so remarkable that one might well see a relationship of cause and effect, as though the Arabic language, even its system of writing had been created for the needs of this cause: the judaisation of Arabia.

For the time being, let us consider only the emergence of the writing. Blachère himself noted: “The formation and development of Arabic writing coincide so well, chronologically, with the introduction of monotheistic doctrines in the Arab territories, that it is very difficult not to see a mutual relationship between these two facts.” ●

After having recalled that “the Ṯamūd, the Liḥyān and the Safaïtes had continued to use an alphabet of South Arabic origin to write their language,” Blachère adds: “The great revolution that was to take place, from the 6th century onwards, was the abandoning of this system in favour of another, derived from Aramaic script. Such a revolution seems to be explained both by the square, rigid, thus unwieldy appearance of the ṯamūdeo-liḥyānite alphabet and by the regression of these Aramaic cultural groups.”● How did “the transition from this Aramaic cursive script to the Arabic script per se” come about? This is what Blachère tried to explain by the comparative study of the only four epigraphic documents in our possession that predate the Qurʾān.●

The first may be dated “from the end of the 3rd century.” It is a bilingual, Greek and Aramaic-Nabataean inscription, found west of Hauran, at Umm-al-Jimāl. Its “written form is characterised by the addition of numerous ligatures between the letters.”

The second document dates from the beginning of the 4th century. Its writing differs little from the first since it is close to it in time and space: “Nevertheless, the number of ligatures has increased, the letters have a more rounded shape while others, such as the ʿayn or the final syllable īn of the plural, announce the system known as ‘Kufic’.” This inscription, written in the Nabataean-Arabic language and containing Aramaic expressions, was discovered on the lintel of the door of a mausoleum near Namāra at the location of an ancient Roman post, east of Djebel Druze, on the borders of Syria. It allows us to date precisely the death of a king of Ḥīra,● Imru l-qays son of Amr (December 7, 328).

A century and a half after these two inscriptions, which constitute a first group that we shall describe as “proto-Arabic,” two other documents, once again in the Syro-Mesopotamian region, literally bring to light for the first time, texts that are truly “Arabic,” which offer all the characteristics of the writing called “cursive”. It just so happens that they are Christian texts.

The first is engraved alongside two dedicatory inscriptions, in Syriac and Greek, dated 512 a.d. on the lintel of the gate of a basilica dedicated to Saint Sergius, in the Aleppo region. The Arabic text “seems to have been added subsequently,” Blachère writes; “it does not translate the Greek-Syriac dedication but, on two lines, gives the names of the founders, all Aramaean.”●

The second is a bilingual Greek-Arabic inscription discovered in Harrān, north west of Djebel Druze. It “represents the dedication of a martyrium which, according to the Greek text, is dedicated to Saint John the Baptist,” and bears the date of 568 a.d. “With this clearly dated document, we have the specimen of a definitively constituted graphic system,” the very one that will be used for writing Sūrah 1.

In fact, it should be pointed out that in the present state of our knowledge, all the other documents using this graphic system date from after this Sūrah, beginning with the stele of Fosṭāt, in Egypt, dated 652.● This stele is contemporary with the first Egyptian papyri that appear in the second part of the 7th century, in which Arabic writing takes on an appearance more dynamic, more cursive than on steles and monuments, on which it continues to be used until around 718.

Sūrah 1 can thus be situated very precisely between the Christian inscription of Harrān, in Syria (568), and the stele of Fosṭāt, in Egypt (652), which can be qualified as “post-Islamic.” Now, as we have seen, this Sūrah is a Jewish prayer, in Arabic of course, but an Arabic that can be described – consistent with our literal analysis – as “Talmudic,” according to Father Hruby’s definition of the Talmudic language: a “half Hebraic, half Aramaic jargon.”●

THE AUTHOR AND THE LANGUAGE

We make no secret of the fact that we will surprise many readers by posing the question about the identity of the author of Sūrah 1. Whoever judges equitably, however, will admit that it would be contrary to scientific method, after Father Lammens’ critical remarks on the manner in which the sīra was composed, not to re-examine the attribution of this Sūrah and the whole Qurʾānic corpus to “Muḥammad.”

The question of the author’s identity is inseparable from that of the language. Blachère put it in perfectly clear terms. On the one hand, “the Muslim theory, according to which ‘literal’ Arabic is derived from the Meccan dialect considered as the linguistic norm, encounters insurmountable difficulties.”● On the other hand, Blachère is unable to conceive of a deliberate creation: “Let us note, however, that the hypothesis of an artificial and meditated creation seems rather unacceptable.”● Although he does not say why, the hypothesis did nevertheless dawn on him, and not without reason. Indeed, it suffices to reconstitute the great phases of the history of Arabia that were a prelude to the appearance of both Sūrah 1 and the language of which it is the first literary attestation, for this “hypothesis of an artificial and meditated creation” to become self-evident, while at the same time it allows the extraordinary personality of the author who was its creator to transpire.

A CHRISTIAN ATTEMPT TO PENETRATE INTO THE HIDJĀZ, IN THE 6TH CENTURY

In the genesis of the Arabic language and its written form, Sūrah 1, a Jewish prayer, can be placed after the inscription of Harrān, a Christian inscription dated 568. Now, this date is also that of a large-scale Christian undertaking to colonise and convert the whole of Arabia. The Jews powerfully and victoriously fought this enterprise. These facts were erased from the memory of peoples by the Muslim legend. It is necessary to reconstitute the whole history.

With the exception of the South, or “Arabia felix,” the peninsula between the Red Sea, the Sea of Oman and the Syrian desert appears to be a place of caravan passage and a reservoir of nomads without political organisation, far from all the great movements of civilisation. The Arabs only entered history insofar as they left Arabia and settled in Syria, Palestine, Egypt and Persia.

THE ROMAN PROVINCE OF ARABIA

Thus, in 9 b.c., an Arab named Areta was reigning in Petra over the Nabataeans who are Arabs ethnically, and even extended his kingdom as far as Damascus, with the support of the Romans.● Increasingly drawn into the orbit of Roman politics, the Arab kingdom was finally annexed to the empire by the legate of Syria, who took Petra (105). The ancient kingdom was constituted as a province under the name of Arabia with Bosra as its capital. Almost the whole of the peninsula, however, remained outside its limits.

This distant province was, however, sufficiently integrated into the empire to provide it, one hundred and forty years after its annexation, with an emperor, a Christian emperor: Philip (244-249). The reorganisation that it underwent during Diocletian’s administrative reform around 295 did not mark a further penetration into the peninsula. On the contrary, the southern part of the province was separated from it and attached to Palestine, “presumably in order to better distribute the military forces: Diocletian must have felt that the danger was no longer in Jerusalem, and that the 10th Fretensis legion would render more services by containing the threatening Arab invasions in Aila, which led to the attachment of this garrison to the district of the praeses Palaestinae.”●

DESERT ARABIA

The vast majority of Arabs, grouped into tribes, continued in fact to lead a nomadic way of life outside the limits of the Roman province, which they constantly threatened with their incursions. “They were called scenite Arabs, living in tents, Skènitai Arabs; and they ended up being called Saraceni (in Pliny, Arraceni), Saracens, or better Saracenes, which was first given to a few pillaging tribes, as well as the name Agareni or Agraei, first given to nomads from the region east of Nemara, and which is used by some Byzantine historians to designate Arabs not incorporated into the empire.”●

The lives of the holy hermits of the desert are filled with stories illustrating the prestige of the “roumis” monks on the Saracens. These nomads continued to make bloody incursions into Palestine and massacred the hermits of the Sinai desert. Sometimes they converted, following the example of their leader, enthralled by the charisma of some great “marabout,” whose faithful allies they became.

This influence, however, did not lead to the penetration of the Christian civilisation in the centre of the peninsula. On the contrary, it led to an immigration of nomads to Palestine where they were catechised, converted and assimilated little by little. This is how Saint Euthymius founded Paremboles by converting an entire tribe who had passed with bag and baggage into Christian land in order to escape Persian reprisals: the chief of this tribe had refused to serve as an antichristian police force for the king of Persia on the border of the two empires. When he died (January 20, 473), Saint Euthymius left Arab disciples: Saint Elijah, the future patriarch of Jerusalem, and Stephen who was superior of the monastery.

THE KINGDOM OF THE ĠASSĀNIDE CHRISTIANS, VASSAL OF BYZANTIUM

Without warning, however, incursions of pillagers from the South continued. Thus, in order to assure the peace and security of the province of Arabia, the Romans were led to attempt to colonise the “Saracen” nomadic tribes. The first outline of a political organisation in central Arabia dates from that moment: the institution of phylarchs under the supervision of military authority was a real gain in authority for the tribal chiefs; It also furthered Roman and Christian influence in the desert.

In 498, the Byzantine general Romanos pursued a sheikh named al-Ḥarīṯ, the leader of a band of plunderers, who was making incursions into Palestine. Romanos’ momentum took him as far as the island of Jotabe, at the mouth of the Gulf of Akaba, which had been conquered by the Persians in 473. They had given the Jews there semi-autonomy.● Emperor Anastasius I (491-518) maintained the Jews’ status of autonomy and concluded a treaty of friendship with Al-Ḥarīṯ, whose people, the Kindits, would henceforth wage war on behalf of the Romans, against the Kingdom of Ḥīra, allied to the Persians.

Justinian in his turn made an alliance with the Sheikh Abū Karib who gave him the coast stretching from the southern limit of Palestine to the territory of the Maadenians, to a depth of a ten days’ march inland! It was a forest of palm trees, and taking possession of it remained problematic. Abū Karib, however, acted as a faithful ally, continuing to sell as slaves in Persia and India those whom he captured in waging war on behalf of the Romans against the Jews of Palestine.

In the meantime, Al-Munḏir, the King of Ḥīra, the vassal Arab prince of the king of Persia, increased the numbers of incursions and, defeated, took refuge in the South only to return at the head of new devastating bands. In 530, Saint Sabas, a disciple of Saint Euthymius, asked the emperor for permission to build a fort to protect his monks.

Justinian then gave Al-Ḥarīṯ a title even better than phylarch: the title of “patrician,” accompanied by all the epithets that in Byzantium designated the members of the highest aristocracy. As for the Arabs, they called him “king,” the very title given to the emperor.

This initiative, however, did not result in an extension of Christian and Roman influence in the Ḥiḏjāz. By attracting Al-Ḥarīṯ northward to establish him phylarch of the Saracens of Palestine, Justinian was abandoning the tribes of Kinda and Maad to the poor and nomadic anarchy of the Nejd.

THE KINGDOM OF ḤĪRA, THE VASSAL OF THE PERSIANS

Moreover, entirely subject to immediate war aims, this alliance did not result in a significant influence of Christian civilisation over born quarrellers who were paid by the “roumis” to wage war on the detested enemy tribes: those bribed by the Byzantium’s adversary, the king of Persia, that had also been elevated to the status of a “kingdom” since the 4th century.●

Baron has clearly shown that this Nestorian Christian kingdom of the Laẖmides, set up by the Persians against the Arab kings subject to Roman and Christian influence, appeared in the 6th century as an auxiliary to Jewish ambitions on Arabia, much more than as a factor in the spread of Christianity.

How long had the Jews been influencing this precious auxiliary? The inscription of Namâra, already mentioned above, discovered by René Dussaud on the borders of Syria, makes it possible to date with precision the death of a king from Ḥīra: Imru l-qays ben Amr (December 7, 328). It tells us that Imru l-qays was a powerful leader, capable of waging war not only against the Arab tribes of the North, his neighbours, but also as far as southern Arabia against the king of Saba and Ḏū Raydān, the pagan Schamir Yuharisch, an adorer of Astarte.

The title of this prince, “king of all the Arabs,” bears mention of the tādj, the “diadem” granted to him as an insignia of supreme power by the Persians,● two hundred years before the Romans raised the Ġassānides to the same dignity.

Al-Munḏir III (505-554) never ceased to harass the Romans and their allies, remaining fiercely pagan in the midst of a Persian Nestorian Christendom; robbing the hermits of Palestine, offering human sacrifices to his god el-Ozza. Thus he sacrificed the son of the Ġassānides Al-Ḥarīṯ, his enemy, whom he had surprised around 544 in a peaceful grazing expedition. On another occasion, he immolated four hundred nuns captured in Emesa.●

Above all, he supported the Jews of Yemen against Byzantium.

A JEWISH KINGDOM IN THE LAND OF SABA

John of Ephesus relates that a war broke out at the beginning of the 6th century between an Ethiopian prince named Aidog and a king of the Homerites called Dimion. In retaliation for the persecutions suffered by the Jews in Roman lands, Dimion arrested the Roman merchants who were taking the road through Yemen from India to the Red Sea. By this simple fact, we can estimate the power of the Jews in Yemen.

The trade, thus diverted from its usual route, was as a consequence moved further away from Ethiopia. The king of the Ethiopians vowed, when he went to war against the Ḥimyarites, to convert to Christianity if he was victorious. Having won the war and conquered Yemen, where he installed a viceroy, he asked Emperor Justin I (518-527) for a bishop and priests. Justin sent John the Paramonar of the Church of Saint John of Alexandria. Churches were built all over the country, including newly conquered Yemen, and many converted to Monophysite Christianity, and not to Arianism as in the time of Theophilus of Dibus.●

The “national” reaction against this Christian party protected from abroad was immediate. It was a Jewish reaction. And it took on all the characteristics of a large-scale enterprise, probably deployed from the school of Tiberias with which the Jews of Yemen were in constant contact, as the letter of Simeon of Beth Arsham, already quoted, attests: “These Jews who are in Tiberias send their priests year after year and season after season to stir up trouble against the Christian people of the Ḥimyarites.” The discovery of Ḥimyarite graves at the Beth Sheʿarim cemetery has revealed that such relations had already existed for a long time.

The anti-Ethiopian reaction was led by Ḏû Nuwâs who, according to Simeon’s letter, took advantage of the death of the viceroy established by the Ethiopians to seize power. He was “of the Jewish religion, like several of his predecessors.”● He sought help from and alliance with the king of Ḥīra, Al-Munḏir, an ally of the Persians, and from Persia itself. Simeon also tells that he saw at Ḥīra a messenger from the king of Ḥimyara sent to the Laẖmide king, carrying a letter that ended thus: “As for the Jews in your dominion, help them in all things and let us know whatever you need in your dominion in return for this help, so that we can send it to you.”●

Ḏû Nuwâs’ grand design, however, turned into a disaster. First, his enemies, the Abyssinian and Ġassānides Christians, were constantly harassing the Jewish settlements in the North with the support and subsidies of Byzantium, as we mentioned above. All Justin had to do was to incite, through the Patriarch Timothy of Alexandria, Eleasius, King of Abyssinia, to intervene against “the abominable and lawless Jew.” Eleasius, with Justin’s consent, placed an embargo on the ships that were stationed in his ports. At Jotabé itself, the Jewish community could not oppose the departure of seven Byzantine merchant ships stationed on the island, sent to assist the Abyssinian expedition against the Jews of Ḥimyara (523-525).

Meanwhile, the Jewish king received only verbal encouragement from the Sassanid king, Kavadh I. “Persia, it is true,” writes Baron, “had a real interest in staving off Christian hegemony on the Arabian Peninsula. Since the Persian rulers did not have any hope of establishing there the Zoroastrian state religion, which had little missionary success outside the imperial frontiers, they often hesitated between helping the native pagans to maintain their pagan religions and encouraging them to adopt Judaism or Christian Nestorianism.● This Christian sect feared the expansion of orthodox Byzantium almost as much as the Jews did. Moreover, at that particular time (523-525), the Sassanid Empire was still recovering from the internal anarchy engendered by the Mazdaist movement which a quarter of a century earlier had led Kavadh I to summon the Huns of Central Asia to his aid. ”●

The Christians were thus victorious. The Negus killed the king of Ḥimyar and established a Christian viceroy named Esimiphaios, chosen from among the Christians of the country to become their representative. This victory corresponds, with perfect synchronism, to the uprising of the Jews at Tiberias and its crushing, which ended with the closure of this school (527). In addition, the Jews of the island of Jotabé had their autonomous status withdrawn by Justinian (535).

Esimiphaios, Viceroy of the Negus, received an embassy from Justinian, led by Julian, to organise the silk trade through Yemen and Abyssinia, and to divert it from the Persian lines. Esimiphaios, like his suzerain of Axum, promised his good will, but could do nothing against the monopoly of the Persians who, in India, bought all available silk.

A former slave named Abramos, who became governor of the country, rose up against Esimiphaios and was victorious over two armies sent against him successively from Abyssinia. He remained sole master of Yemen, but he paid tribute to the Negus.

Abramos was not only Christian but pious and represented as such by all sources. John of Ephesus portrays him up as a fervent Monophysite. Through epigraphy we have solid information on the reign of Abramos, a counterproof confirming the Judaic origin of the epigraphy of the earlier kings. The inscription Glaser 618, which begins with the well-known invocation to er-Raḥmān, is clearly Christian: “By the power, favour and mercy of the Merciful and of his Messiah and of the Holy Spirit.” Abramos gives himself the ancient title of the Ḥimyarite kings: “King of Saba, and of Ḏū Raydān and of Hadhramōt and of Yemenat and of their Arabs in both mountain and plain.”

Fifty years later, Yemen shook off the Abyssinian yoke, only to fall under that of the Persians (572). They did not return their “fiefdom” to the Jews. “Nevertheless,” Baron writes, “the Ḥimyarite Jews, whether of Jewish or Arab extraction, survived the harsh Abyssinian regime, just as their descendants were to survive many persecutions later and even in modern times. As is well known in recent decades, Yemeni Judaism continued to play an important role in its own country while contributing to the establishment of the Jewish homeland in Palestine.”●

If this fact is well known in the history of recent decades, it is less well known in ancient times, for which it is nevertheless singularly enlightening, in order to unravel all the confused and still poorly known events that drastically changed the Near East at the beginning of the 7th century.

PREDOMINANCE OF JUDAISM IN ARABIA IN THE BEGINNING OF THE 7TH CENTURY

Let us summarise the results of this broad retrospective. The Jews have appeared to us to be at work in this desert since the most remote times. It, however, was with the opening of the Christian era and under the influence of the great empires that the peninsula awakened to political life. In the North, the rivalry between Byzantium and Persia favoured the gathering of Arab tribes and their unification in the service of these empires. For the Romans, however, this venture resulted in attracting nomads towards the North. They would eventually settle in Syria, Palestine, Egypt, without bringing any influence to bear in return on the peninsula. The failure of Justinian’s attempt to set up a pro-Roman kingdom in the Ḥiḏjāz is significant in this respect: once al-Ḥarīṯ had settled in Palestine, he lost all influence over his former tribes in the Ḥiḏjāz.

On the Persian side, the kingdom of Ḥīra seems to have played a greater role in awakening Arabia to political life. First of all, it is more ancient, and from the 3rd century onwards, it had contacts with the South. These relations, however, are difficult to define, and even more so the nature of the influences they conveyed. As Aigrain remarks, this lacuna is due to the fact that “we obtain our information from Greek or Syrian authors” and that “the Arab sources are, for this period, richer in untenable legends than in proven facts.”● Sufficient evidence, however, has allowed us to see in the kingdom of Ḥīra a political ally of the Jews of Yemen, in conjunction with the Persians and under their dependence.

Thus, at the end of the 6th century, the outcome of the Persian-Roman rivalry was, politically, clearly in favour of the Persians. In the south of the Arabian Peninsula, Abyssinia was definitively pushed back to the other side of the Red Sea by the Persian conquest, and this was a gain for the Jews. In the North, “it was especially at the end of the century, when the Laẖmid king Nuʿmān III, deeply impressed by the victorious alliance of Emperor Mauritius with Chosroes II, was formally converted to Christianity, that the old and important Jewish communities of this entire frontier territory must have felt seriously threatened. However, this danger disappeared when Nuʿmān was captured by Chosroes II in 602, at the beginning of the Persian campaign against Byzantium, and his kingdom was transformed into a Persian province.”● In the West, the Ġassānid barrier created by Justinian between the Hijaz and Palestine, which made the position of the Jews so precarious, has disappeared since the death of el-Mundir (582).”●

Thus the elimination of the Roman Empire benefitted the Persian Empire and everywhere meant the elimination of Christian penetration, which benefitted Judaism. Were it not for the Roman domination in Palestine, the Ḥiḏjāz would have appeared to be, after 584, like a veritable Israelite province, in continuity with the ancient Land of the ancestors.●

It was there that the Jews, tireless colonisers, reestablished their “fief” that had been dismantled in Yemen: “The Jews of Yathrib, Khaibar and Teima seem to have pioneered the introduction of advanced irrigation and soil cultivation methods. They developed new arts and crafts, from metalworking to fabric dyeing and fine jewellery, and taught the neighbouring tribes more modern methods of exchanging goods and money. Most of the agricultural terms and names of tools in pre-Islamic Arabic poetry [sic!] or in the Qurʾān are borrowed from the Aramaic language [...]. Thanks to their irrigation system, to the observance of certain diets, and especially by building their castles on hills instead of valleys infested with fevers, the Jews were thus the first to fight against contagious and deadly diseases [...]. In short, in the few generations under Jewish rule, the main regions of the north almost reached the high level of southern civilisation which had long ago earned Ḥimyara and its surrounding areas the Roman qualification of Arabia Felix.”●

Were a Jewish kingdom to be re-established in Jerusalem, the Ḥiḏjāz would quite naturally be englobed in a “Greater Palestine” surpassing the Empire of Solomon itself!

This is precisely the immense hope that galvanised the Jews of Palestine and Arabia to the borders of Yemen, and all the Jews of the diaspora at the beginning of the 7th century.

Al-Nuwayrī (1279-1333) was an Arab historian and jurisconsult in the service of the Mameluke Sultans of Egypt. He was born in An Nuwayrah, Egypt. He wrote an encyclopaedia entitled Nihayat al-arab fi funûn al-adab (All You Wish to Know about Belles-Lettres), in 30 volumes, covering all aspects of human history, as well as fauna, flora, laws, geography, the art of governing, poetry, recipes of all kinds, humorous stories and the revelation of Islam. He was also the author of Chronicle of Syria and History of the Almohads of Spain and Africa.

Jacqueline Pirenne, was an archaeologist. She received a degree in philosophy (Paris, 1939), then in oriental philology and history (Louvain, 1951). In 1957, she joined the CNRS [Centre national de la recherche scientifique = National Organisation for Scientific Research. The CNRS is a multidisciplinary research organisation, established by the French government in 1941 and affiliated to the Ministry of Education. It receives state funding and its members, who are highly qualified specialists in their fields, are engaged in research in the areas of science, engineering, humanities and social sciences]. She is the author of Corpus des inscriptions et des antiquités Sud-Arabes, published by the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (Louvain, Belgium, 1977), comprising Volume I, Section 1: Inscriptions; Section 2: Antiquities; and Volume II: Systematic General Bibliography.

Jacqueline Pirenne, Corpus des inscriptions et antiquités sud-arabes, Peeters, Louvain, 1977, Vol. 1, p. XXXI.

Father Henri Lammens. Prominent Flemish Belgian-born Jesuit and orientalist (1862–1937). Professor at Saint Joseph’s University in Beirut, Lebanon, he was the first to venture applying the rules of the modern historical and critical method to the Qurʾān. Father Lammens based his work on the Professor Ignác Goldziher concerning the historical value of the Tradition. He adopted Goldziher’s viewpoint and pursued the inquiry. Lammens’ conclusions are firm and represent a considerable advance over Goldziher’s. The latter had shown the profoundly “tendentious character” of the Tradition. Father Lammens showed its “apocryphal” nature. He positively demonstrated that the ḥadīṯs are nothing but pure inventions, that the so-called ‘eyewitnesses,’ the authorities of the Ḥadīṯ, are fictitious. Thus, the Sīrah has no historical basis other than the Qurʾān, of which it is nothing more than an imaginary elaboration: “Since the Tradition arises from the affirmations recorded in the Qurʾān,” Father Lammens stated, “it does not provide a verification or complementary information, but an apocryphal elaboration.” He was therefore able to conclude that “the Sīrah remains to be written, just as the historical Muḥammad remains to be discovered.” To do this he advocated rejecting the ‘Tradition’ in its totality, replacing its fanciful exegesis by a scientific exegesis. Although he recommended this, he never carried out this work. When Father Lammens passed away, the Jesuits of Beirut put his works under seal, and since then it has been a law of Islamology to ignore his discoveries.

Father Henri Lammens. Prominent Flemish Belgian-born Jesuit and orientalist (1862–1937). Professor at Saint Joseph’s University in Beirut, Lebanon, he was the first to venture applying the rules of the modern historical and critical method to the Qurʾān. Father Lammens based his work on the Professor Ignác Goldziher concerning the historical value of the Tradition. He adopted Goldziher’s viewpoint and pursued the inquiry. Lammens’ conclusions are firm and represent a considerable advance over Goldziher’s. The latter had shown the profoundly “tendentious character” of the Tradition. Father Lammens showed its “apocryphal” nature. He positively demonstrated that the ḥadīṯs are nothing but pure inventions, that the so-called ‘eyewitnesses,’ the authorities of the Ḥadīṯ, are fictitious. Thus, the Sīrah has no historical basis other than the Qurʾān, of which it is nothing more than an imaginary elaboration: “Since the Tradition arises from the affirmations recorded in the Qurʾān,” Father Lammens stated, “it does not provide a verification or complementary information, but an apocryphal elaboration.” He was therefore able to conclude that “the Sīrah remains to be written, just as the historical Muḥammad remains to be discovered.” To do this he advocated rejecting the ‘Tradition’ in its totality, replacing its fanciful exegesis by a scientific exegesis. Although he recommended this, he never carried out this work. When Father Lammens passed away, the Jesuits of Beirut put his works under seal, and since then it has been a law of Islamology to ignore his discoveries.

Theodor Nöldeke. German orientalist (1836-1930). He studied in Göttingen, Vienna, Leiden and Berlin. Along with Ignaz Goldziher, he is considered the founder of modern Islamic studies in Europe. In 1859 his history of the Qurʾān won for him the prize of the French Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, and in the following year he rewrote it in German (Geschichte des Qorâns). Nöldeke admitted: “In the end, I renounce exploring the mystery of the historical personality of Muḥammad.” Nöldeke is best known for his reordering of the 114 Sūrahs of the Qurʾān to match what he considered to be their true historical occurrence. Nöldeke based this work on the sequence of revelation with the development of content and the origination of new linguistic styles. The Nöldeke Chronology divides the Sūrahs of the Qurʾān are into four groupings: the First Meccan Period, the Second Meccan Period, the Third Meccan Period, the Medinese Period. Nöldeke considered this arrangement to be more coherent and comprehensive. Despite this attempt made by Noldëke, and later on by Schwally, Blachère, etc., Brother Bruno believes that there is no reason to give the “Sūrahs” an order different from the one found in the accepted “vulgate.”

Theodor Nöldeke. German orientalist (1836-1930). He studied in Göttingen, Vienna, Leiden and Berlin. Along with Ignaz Goldziher, he is considered the founder of modern Islamic studies in Europe. In 1859 his history of the Qurʾān won for him the prize of the French Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, and in the following year he rewrote it in German (Geschichte des Qorâns). Nöldeke admitted: “In the end, I renounce exploring the mystery of the historical personality of Muḥammad.” Nöldeke is best known for his reordering of the 114 Sūrahs of the Qurʾān to match what he considered to be their true historical occurrence. Nöldeke based this work on the sequence of revelation with the development of content and the origination of new linguistic styles. The Nöldeke Chronology divides the Sūrahs of the Qurʾān are into four groupings: the First Meccan Period, the Second Meccan Period, the Third Meccan Period, the Medinese Period. Nöldeke considered this arrangement to be more coherent and comprehensive. Despite this attempt made by Noldëke, and later on by Schwally, Blachère, etc., Brother Bruno believes that there is no reason to give the “Sūrahs” an order different from the one found in the accepted “vulgate.”

Nöldeke, Geschichte des Qorans, p. 110

Ryckmans, Les religions arabes préislamiques, Louvain, 1951, 2e éd., p. 47.

_______________________

Gonzague Ryckmans. Belgian priest, Arabist and professor (1887-1969). He taught at the Catholic University of Leuven, where he had begun his studies in philosophy and from which he obtained his first doctorate in 1908. From 1908 to 1911, he continued his studies in theology and pastoral ministry at the Major Seminary at Mechlin. From there, he was sent to the École biblique de Jérusalem in 1911, in order to specialise in the field of biblical exegesis, history of the Ancient East and Oriental Languages. Upon return to Belgium in July 1914, he participated in the trench warfare as stretcher-bearer and chaplain. He was gassed while administering the Sacrament of Extreme Unction to wounded soldiers. In 1919, after the war, he obtained his doctorate in Semitic languages. The publication of his thesis put him in contact with Father J.B. Chabot who convinced him to spend a year in Paris where he met all the great French orientalists and became familiar with the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum. From 1920 to 1930, he was professor of exegesis at the Major Seminary of Mechlin. In 1930, he obtained a professoriate at the Catholic University of Leuven and was entrusted with the courses of Hebrew, Aramaic, Akkadian, and comparative grammar of Semitic languages. In 1936, he became secretary of the newly founded Orientalist Institute, while acting as secretariat for the review Le Muséon. His scientific activity led him essentially in three directions: the publication of epigraphical texts, the creation of work instruments and the drafting of various synthesis, both philological and historical.

Gonzague Ryckmans. Belgian priest, Arabist and professor (1887-1969). He taught at the Catholic University of Leuven, where he had begun his studies in philosophy and from which he obtained his first doctorate in 1908. From 1908 to 1911, he continued his studies in theology and pastoral ministry at the Major Seminary at Mechlin. From there, he was sent to the École biblique de Jérusalem in 1911, in order to specialise in the field of biblical exegesis, history of the Ancient East and Oriental Languages. Upon return to Belgium in July 1914, he participated in the trench warfare as stretcher-bearer and chaplain. He was gassed while administering the Sacrament of Extreme Unction to wounded soldiers. In 1919, after the war, he obtained his doctorate in Semitic languages. The publication of his thesis put him in contact with Father J.B. Chabot who convinced him to spend a year in Paris where he met all the great French orientalists and became familiar with the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum. From 1920 to 1930, he was professor of exegesis at the Major Seminary of Mechlin. In 1930, he obtained a professoriate at the Catholic University of Leuven and was entrusted with the courses of Hebrew, Aramaic, Akkadian, and comparative grammar of Semitic languages. In 1936, he became secretary of the newly founded Orientalist Institute, while acting as secretariat for the review Le Muséon. His scientific activity led him essentially in three directions: the publication of epigraphical texts, the creation of work instruments and the drafting of various synthesis, both philological and historical.

The Book of Exodus 33:19

Yahweh said: “I will make all My goodness pass before you, and will proclaim before you My name ‘Yahweh’; and I will be gracious to whom I will be gracious, and will show mercy on whom I will show mercy.”

The Book of Exodus 34:6

Yahweh passed before him [Moses], and proclaimed: “Yahweh, Yahweh, a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness.

Qurʾān 1:2

Love to the God Master of the centuries (…)

As exemplified in a 5th century inscription discussed below under the heading “A JUDAISING MONOTHESISM” and in the Jamme 664 inscription quoted by Biella, Dictionary of Old South Arabic, 1982, article ḤMD, p. 179: rbHD bmḥmd. The Jamme 644 inscription is a dedicatory inscription written in Sabaic that Albert Jamme discovered incised into the base of a statue in a temple during the excavations he was carrying out in Maḥram Bilqîs (Mârib), Yemen, in 1962. We will examine this inscription and its interpretation in our Volume II.

________________

Joan Copeland Biella (1947-....) was an American researcher and member of the W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research, Jerusalem (1982).

J.W. Hirschberg, Jüdische und christliche Lehren im vor und frühislamischen Arabien, Cracow, 1939, p. 68.

_______________________

Joachim Wilhelm Hirschberg (1903-1976) became a specialist of the history of the Jews in Islamic countries. Born in Tarnopol (administered at that time by the Austro-Hungarian Empire), he studied in Vienna at the University and the Rabbinical Seminary. From 1927 to 1939, he was rabbi in Czestochowa and in 1943 immigrated to Palestine. He was a research fellow at the Hebrew University from 1947 to 1956 and from 1960 was professor of history at Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan, where he headed the Institute for Research on the History of the Jews in Eastern Countries. Hirschberg wrote extensively on the history of Jews in Islamic lands, his major work being a two-volume history of the Jews in North Africa.

The Gospel According to Saint Mark 9:5

And Peter said to Jesus: “Master, it is well that we are here; let us make three booths, one for You and one for Moses and one for Elijah.”

The Gospel According to Saint Mark 11:21

And Peter remembered and said to Him [Jesus]: “Master, look! The fig tree which You cursed has withered.”

The Gospel According to Saint Mark 14:45

And when he [Judas] came, he went up to Him [Jesus] at once, and said: “Master!” And he kissed Him.

The Book of Jeremiah 31:33-34

33 “This is the Covenant which I will make with the house of Israel after those days,” says Yahweh: “I will put My law within them, and I will write it upon their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be My people. 34 And no longer shall each man teach his neighbour and each his brother, saying, ‘Know Yahweh,’ for they shall all know Me, from the least of them to the greatest,” says Yahweh; “for I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more.”

The Book of Isaiah 54:13

All your sons [Israel’s] shall be taught by Yahweh, and great shall be the prosperity of your sons.

The Gospel According to Saint John 6:45

It is written in the prophets: ‘And they shall all be taught by God.’ Everyone who has heard and learned from the Father comes to Me [Jesus].

Read about the history of these rivalries below under the heading JEWISH PROSELYTISM IN YEMEN.

Qurʾān 1:4

King of Judgement Day.

The Book of Psalms 5:3

Hear my cry for help, my King, my God! To you I pray, O Yahweh.

The Book of Psalms 10:16

Yahweh is King forever and ever; the nations shall perish from His land.

Qurʾān 1:2

Love to the God Master of the centuries (…)

The Book of Hosea 6:6

“For I [Yahweh] desire steadfast love and not sacrifice, the knowledge of God, rather than burnt offerings.”

The Book of Jeremiah 31:33

“This is the Covenant which I will make with the house of Israel after those days,” says Yahweh: “I will put My law within them, and I will write it upon their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be My people.”

Chanoine René Aigrain Professor and author (1886-1957). He entered the Major Seminary of Poitiers in 1904 and was ordained priest in 1909. He became professor of the History of the Middle Ages at Université catholique d’Angers in 1923, where he taught until 1951. He was appointed Honorary Canon of Poitiers in 1934. From 1922 to 1924, he contributed the article Arabia to the Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques. It is a complete encyclopaedia on the question of Christian origins in Arabia, supported by a rigorous critical analysis of the positive data known at the time. In it, he rightly concluded that “we can no longer deal with the history of Muḥammad by using, as several of his biographers do, the Sīrah as a basis.” Unfortunately, when it came Islam, he abandoned this fruitful point of view, simply reverting to the use of what is considered to be traditional data, immediately adding to the above remark: “This does not mean that we must retain nothing from it [the Sīrah], which would make it absolutely impossible for us to know the life of the Prophet.” This means that even outside the Sīrah there is not one single positive fact that attests to Muḥammad’s historical existence.

Chanoine René Aigrain, Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques, col. 1233.

Joseph Halévy (1827-1917) was a naturalised French Jewish orientalist born in Edirne (Ottoman Empire). In 1867-1868 Joseph Halévy was entrusted with a research mission to Ethiopia by the Alliance Israélite Universelle. On this occasion, he was the first Western Jew to come into contact with the Falashas, a community of Ethiopian Jews and to have brought back a detailed description of their way of life.

Joseph Halévy (1827-1917) was a naturalised French Jewish orientalist born in Edirne (Ottoman Empire). In 1867-1868 Joseph Halévy was entrusted with a research mission to Ethiopia by the Alliance Israélite Universelle. On this occasion, he was the first Western Jew to come into contact with the Falashas, a community of Ethiopian Jews and to have brought back a detailed description of their way of life.

Linguist, archaeologist and geographer, Halévy was a professor of Ethiopian and Sabean languages at the École pratique des hautes études in Paris (1879-1917). He founded the Semetic and Ancient History Review. His most important work was carried out in Yemen for the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres. He travelled throughout this country in 1869 and 1870 in search of the Sabaean inscriptions. The result was a survey of 800 inscriptions of which 686 are in Sabaean, which allowed a first approach to this ancient civilisation. He was the first to propose a partial deciphering of the Sabean language.

In the specifically Jewish field, the most remarkable of Halevy’s works is to be read in his Biblical Research. In it he analyses the first twenty-five chapters of Genesis in the light of the recently discovered Assyro-Babylonian documents, and he believes that he finds there an old Semitic myth almost completely Assyro-Babylonian, though considerably transformed by the spirit of prophetic monotheism. However, the narratives of Abraham and his descendants are considered by him to be fundamentally historical, though considerably embellished, and the work of a single author. Halévy’s scientific activity was very diverse, and his writings on oriental philology and archaeology earned him a worldwide reputation.

Eduard Glaser (1855-1908) was a Jewish Austrian Arabist and archaeologist. He is considered the most important scholar to have studied Yemen being one of the first Europeans to explore South Arabia. He collected thousands of inscriptions in Yemen

Eduard Glaser (1855-1908) was a Jewish Austrian Arabist and archaeologist. He is considered the most important scholar to have studied Yemen being one of the first Europeans to explore South Arabia. He collected thousands of inscriptions in Yemen

While working as a private tutor in Prague, Glaser began studying mathematics, physics, astronomy, geology, geography, geodesy and Arabic at the Polytechnic in Prague until 1875. Glaser successfully concluded his studies in Arabic, in Vienna, and enrolled thereafter in an astronomy class. An important turning point in his academic education came in 1880, when Glaser enrolled in the classes of David Heinrich Müller, the founder of South Arabian studies in Austria, for the study of Sabaean grammar. Müller suggested to him that he travel to Yemen, for the purpose of copying down Sabaean inscriptions. A scholarship from the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres in Paris enabled him to make his first trip to Yemen (1882-1884). He returned there on three other occasions (1885-1886, 1887-1888, and 1892-1894).

In addition to his knowledge of Latin, Greek and most of the major European languages, Glaser was proficient in both classical and colloquial Arabic. He saw Yemen as the ideal place for finding basic similarities between the rites of the indigenous peoples and those of the ancient Israelites. He also hoped to identify the geographical names mentioned in the Bible. Glaser was an expert in the Sabaean scripts. Furthermore, his knowledge of Abyssinian history and its language propelled him to examine the connexions between Abyssinia (present-day Ethiopia) and Yemen in ancient times.

Glaser’s good relations with the Turkish governors of Yemen. Allowed him to realise his scientific plans and endeavours. He was able to travel throughout many areas inaccessible to foreigners and, thereby, he was able to copy down hundreds of inscriptions, both in Sabaean and in Arabic.

Unlike Joseph Halévy, who concentrated only on the Yemen’s past, Glaser observed and documented everything he saw in Yemen. He carried out research on the topography, the geology and geography, prepared cartographic maps, took astronomical notes and collected data on meteorology, climate and economic trade, as well as on the nation’s crafts.

From 1895 until his death, Glaser lived in Munich. He dedicated most of his time preparing his scientific material for publication. Despite his great contribution to science Glaser never succeeded in acquiring a suitable academic position and he remained an outsider in the academic circles of Austria, Germany and France. Only about half of Glaser’s 990 copies and imprints of Sabaean inscriptions have been published, and only a small portion of his 17 volumes of diaries, 24 manuscripts and his scientific findings have been studied.

Albert Jamme, La religion sud-arabe préislamique, Histoire des religions, Vol. V, p. 243.

_________________

Albert Jamme (1916-2004) was a Belgian White Father (Missionaries of Africa), who became an orientalist, specialist in Semitic languages, and epigraphist. After secondary school, at the Saint Joseph College in Chimay, he entered the White Fathers (Missionaries of Africa) in Glimes (1934) to study philosophy. Then, he made his novitiate in Algeria, at Maison Carrée (1936). He took his oath in Heverlee (1940) and was ordained priest (1941). After his studies in Louvain, he went to deepen his knowledge for two years at the École Biblique de Jérusalem, then at the Institut des Belles Lettres Arabes (IBLA) in Tunis (1948). After further studies in Louvain (Doctorate of Theology and graduate in Orientalist Studies), he left for Rome (1952). After graduating in Sacred Scripture, Religious Sciences and Education, he was appointed Research Professor at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. (1953-1999.

Albert Jamme (1916-2004) was a Belgian White Father (Missionaries of Africa), who became an orientalist, specialist in Semitic languages, and epigraphist. After secondary school, at the Saint Joseph College in Chimay, he entered the White Fathers (Missionaries of Africa) in Glimes (1934) to study philosophy. Then, he made his novitiate in Algeria, at Maison Carrée (1936). He took his oath in Heverlee (1940) and was ordained priest (1941). After his studies in Louvain, he went to deepen his knowledge for two years at the École Biblique de Jérusalem, then at the Institut des Belles Lettres Arabes (IBLA) in Tunis (1948). After further studies in Louvain (Doctorate of Theology and graduate in Orientalist Studies), he left for Rome (1952). After graduating in Sacred Scripture, Religious Sciences and Education, he was appointed Research Professor at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. (1953-1999.

Cardinal Jean Daniélou (1905-1974) was a French Jesuit priest, renowned theologian. He was created cardinal by Paul VI in 1970. Son of an anticlerical politician and a foundress of Catholic educational institutions for girls, Jean Daniélou studied literature and philosophy at the Sorbonne. In 1929, he entered the Jesuits and devoted his life to teaching. After studying theology at the Catholic Faculty of Lyon, he was ordained priest in 1938. He founded the collection “Sources chrétiennes” in collaboration with Henri de Lubac. After reading Brother Bruno’s scientific dissertations on the results of his historical research on pre-Islamic Arabia and on the Arab Conquest, he encouraged him to publish them.

Cardinal Jean Daniélou (1905-1974) was a French Jesuit priest, renowned theologian. He was created cardinal by Paul VI in 1970. Son of an anticlerical politician and a foundress of Catholic educational institutions for girls, Jean Daniélou studied literature and philosophy at the Sorbonne. In 1929, he entered the Jesuits and devoted his life to teaching. After studying theology at the Catholic Faculty of Lyon, he was ordained priest in 1938. He founded the collection “Sources chrétiennes” in collaboration with Henri de Lubac. After reading Brother Bruno’s scientific dissertations on the results of his historical research on pre-Islamic Arabia and on the Arab Conquest, he encouraged him to publish them.

Ryckmans, Les religions arabes préislamiques, Louvain, 1951, 2e éd., pp. 23, 41; Jamme, La religion sud-arabe préislamique, Histoire des religions, Vol. V, p. 264-265.

Chanoine René Aigrain, Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques, col. 1234-1235; cf. Ryckmans, op. cit, p. 47.

Qurʾān 1

1 Blessed be the name of the God, the Merciful One, full of mercy. (2 …) 3 (…) the Merciful One, full of mercy (…)

Chanoine René Aigrain, Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques, col. 1239.

Philostorgius (368-c. 439) was an historian of the Anomoean (or Eunomian) sect, an extreme division of Arians in the 4th and 5th centuries. Anomoeanism questioned the Trinitarian doctrine of the relationship between God the Father and Christ. Anomoean doctrine held that “the Son is in all things unlike the Father, as well in will as in substance.” Very little is known about Philostorgius’ life. He was born in Cappadocia and lived in Constantinople from the age of twenty. He is said to have come from an Arian family, and in Constantinople soon attached himself to Eunomius, one of the principal propagators of the heresy, who received much praise from Philostorgius in his work. Philostorgius wrote a history of the Arian controversy titled Church History. His original appeared between 425 and 433, and formed twelve volumes bound in two books. The original had been lost. The 9th century historian Photius, however, found a copy in his library in Constantinople and wrote an epitome of it. Others also borrowed from Philostorgius, and so, despite the disappearance of the original text, it is possible to form some idea of what it contained by reviewing the epitome and other references. This reconstruction of what might have been in the text was first published, in German, by the Belgian philologist Joseph Bidez in 1913. Philostorgius also wrote a treatise against Porphyry, which has also been lost.

Theophilus of Dibus dubbed “the Indian” (died 364 a.d.), was an Aetian (an extreme division of Arianism) bishop who fell alternately in and out of favour with the court of the Roman emperor Constantius II. His origin is obscure and accounts for his surname. He came to the court of Constantine I as a young man and was ordained a deacon under the Arian bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia. He was later exiled because Constantius believed him to be a supporter of his rebellious cousin Gallus. He was exiled a second time for his support of the disfavoured theologian Aëtius whose Anomoean doctrine was an offshoot of Arianism.

Theophilus was ordained a bishop and around 354, Emperor Constantius II sent Theophilus on a mission to south Asia via Arabia, where he is said to have converted the Ḥimyarites and built three churches in southwest Arabia. He is also said to have found Christians in India, whence his surname, but many scholars doubt this since the ancient geographers sometimes referred to the Arabian Peninsula as India. In about 356, the Emperor Constantius II wrote to King ʿEzana of Axum requesting him to replace the then Bishop of Axum, Frumentius, with Theophilus, who supported the Arian position, as did the Emperor. This request was ultimately turned down.

On his return to the empire Theophilus settled at Antioch. One of the churches that Theophilus had founded in Arabia during the 4th century was built at Zafar, Yemen and likely destroyed in 523 by the King of Ḥimyar Dhū Nuwās, who had shifted the state religion from Christianity to Judaism. Later in 525, Theophilus’ church was restored by the Christian King Kaleb of Axum following his successful invasion on Ḥimyar.

Homeritae: term used by Greek and Roman authors to designate the inhabitants of the Homerite Kingdom. In more recent times the term was replaced by: Ḥimyarites, the inhabitants of the Kingdom of Ḥimyar.

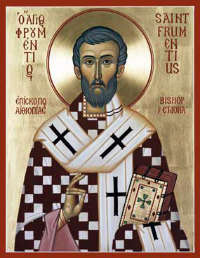

Frumentius (died c. 383) was a Catholic missionary and the first bishop of Axum [present-day Ethiopia]. Frumentius was a Syro-Phoenician Greek born in Tyre [present-day Lebanon]. According to an account given by Frumentius’ brother Edesius, the two boys, while accompanying an uncle on a voyage to Ethiopia, after the local people at one of the harbours of the Red Sea where their ship stopped had massacred all those aboard, sparing only the two boys, they were taken as slaves to the King of Axum. Frumentius and Edesius soon gained the favour of the king, who raised them to positions of trust. Shortly before his death, the king freed them. The widowed queen, however, prevailed upon them to remain at the court and assist her in the education of the young heir, ʿEzana, and in the administration of the kingdom during the prince’s minority. They remained and used their influence to spread Christianity. First they encouraged the Christian merchants present in the country to practise their faith openly.

Frumentius (died c. 383) was a Catholic missionary and the first bishop of Axum [present-day Ethiopia]. Frumentius was a Syro-Phoenician Greek born in Tyre [present-day Lebanon]. According to an account given by Frumentius’ brother Edesius, the two boys, while accompanying an uncle on a voyage to Ethiopia, after the local people at one of the harbours of the Red Sea where their ship stopped had massacred all those aboard, sparing only the two boys, they were taken as slaves to the King of Axum. Frumentius and Edesius soon gained the favour of the king, who raised them to positions of trust. Shortly before his death, the king freed them. The widowed queen, however, prevailed upon them to remain at the court and assist her in the education of the young heir, ʿEzana, and in the administration of the kingdom during the prince’s minority. They remained and used their influence to spread Christianity. First they encouraged the Christian merchants present in the country to practise their faith openly.

When the prince came of age, Frumentius travelled to Alexandria, Egypt, where he requested Athanasius, Patriarch of Alexandria, to send a bishop and some priests as missionaries to Axum. By Athanasius’ own account, he believed Frumentius to be the most suitable person for the mission and consecrated him as bishop. Frumentius returned to Ethiopia, where he erected his episcopal see at Axum, then converted and baptised King ʿEzana, who built many churches and spread Christianity throughout Ethiopia. Frumentius established the first monastery of Ethiopia. In about 356, the Emperor Constantius II wrote to King ʿEzana and his brother Saizana, requesting them to replace Frumentius as bishop with Theophilus of Dibus, dubbed “the Indian,” who supported the Arian position, as did the emperor. Frumentius had been appointed by Athanasius, a leading opponent of Arianism. The king refused the request. Ethiopian traditions credit Frumentius with the first Ge’ez translation of the New Testament.

Chanoine René Aigrain, Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques, col. 1236-1237.

Partisans of an extreme Arianism prevalent amongst a section of Eastern churchmen from about 350 until 381. The history of this new and more defiant Arian school coincides with the life-history of Aëtius, its founder and Eunomius, his disciple. Their Greek watchword was animoios (unlike), for their principal tenet, opposing the Trinitarian doctrine of the relationship between God the Father and Christ, held that “the Son is in all things unlike (animoios) the Father, in will as in substance.” Thus the three names given successively to proponents of this heresy: Aetians, Eunomians, Anomoeans.

Histoire ecclésiastique, Vol. III, 4 – PG 65 481-485. Cf. Chanoine René Aigrain, Dictionnaire d’histoire et de géographie ecclésiastiques, col. 1237. How long had this influence existed? On this point everything is “shrouded in obscurity,” Baron assures us (Histoire d’Israël, P.U.F., 1961, Vol. III, p. 78). Certainly, the biblical accounts of Solomon’s embassies to ‘Ophir’ and of the journey of the Queen of Saba attest to the antiquity of Jewish-Arab relations (1 Kings 9:28-10, 1-13). However, the positive data that we have do not allow us to go back beyond the Christian era. “It seems," writes Baron, “that the first trustworthy historical document of Jewish entry into the south is Josephus’ account of the Jewish soldiers who shared in the disaster of Aelius Gallus” (25 b.c.). Baron infers from this account the antiquity of Jewish relations with the desert tribes, considering that the five hundred Jewish soldiers supplied by Herod were supplied not so much as a fighting force but to facilitate the expedition with their knowledge of the roads and the local population. Cf. Hayyîm J. Cohen, in Encyclopaedia Judaica, Jerusalem, 1971, article Arabia, Vol. III, col. 234: “The role of the Jewish auxiliary contingent sent by Herod to take part in this expedition was to act as a liaison between the Roman army and the Jewish communities of Arabia.”

Gaius Aelius Gallus was the second prefect of the Roman province of Egypt from 26 to 24 b.c. in the reign of Augustus. Aelius Gallus is primarily known for a disastrous expedition he undertook to Arabia Felix (modern day Yemen) by the command of the emperor.

Gaius Aelius Gallus was the second prefect of the Roman province of Egypt from 26 to 24 b.c. in the reign of Augustus. Aelius Gallus is primarily known for a disastrous expedition he undertook to Arabia Felix (modern day Yemen) by the command of the emperor.

An account of the expedition to Arabia Felix, which turned out to be a complete failure, is given by the Greek geographer Strabo, as well as by Cassius Dio and Pliny the Elder. Aelius Gallus undertook the expedition from Egypt, with a view to explore the country and its inhabitants, and to conclude treaties of friendship with the people, or to subdue them if they should oppose the Romans.

When Aelius Gallus set out with his army, he trusted to the guidance of a Nabataean called Syllaeus, who deceived and misled him. Strabo, who derived most of his information about Arabia from his friend Aelius Gallus, wrote a long account of this expedition through the desert. The scorching heat of the sun, bad water, and disease destroyed the greater part of the army; so that the Romans, unable to subdue the Arabs, were forced to retreat. Aelius Gallus returned to Alexandria and was eventually recalled by Augustus for failure to pacify the Kushites.

Constantius II (317-361) was Roman emperor from 337 to 361. Constantius was a son of Constantine the Great, who elevated him to the imperial rank of caesar in 324 and after whose death Constantius became augustus together with his brothers, Constantine II and Constans in 337. The brothers divided the empire among themselves, with Constantius receiving Greece, Thrace, the Asian provinces and Egypt in the east. In 353, Constantius became the sole ruler of the empire after the death of his brothers during civil wars and usurpations. His reign saw constant warfare on the borders against the Persian Sassanian Empire and Germanic peoples. His religious policies inflamed domestic conflicts that would continue after his death. Constantius banned pagan sacrifices by closing their temples. During his reign he attempted to mould the Christian Church to follow his compromise Semi-Arian position, convening several councils. The most notable of these were the Council of Rimini (359) and Seleucia (360) which, however, were not reckoned ecumenical. Constantius is not remembered as a restorer of unity, but as a heretic who arbitrarily imposed his will on the Church.